Category ArchiveTytla

Action Analysis &Animation &Animation Artifacts &John Canemaker &Tytla 16 Apr 2013 05:12 am

Tytla’s Hungry Wolf – recap

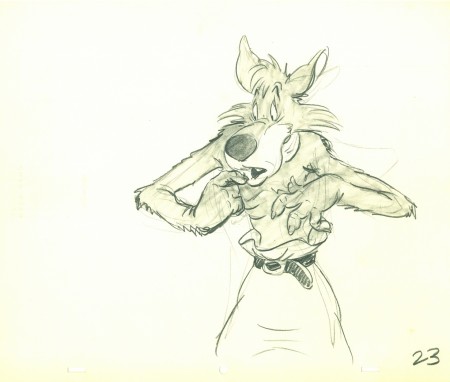

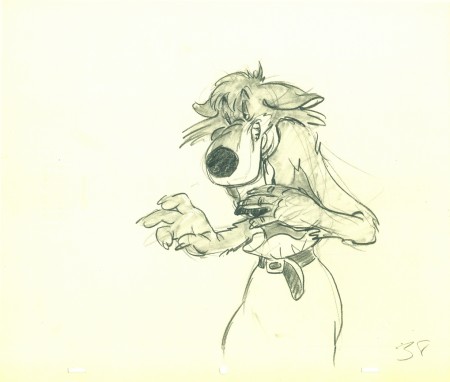

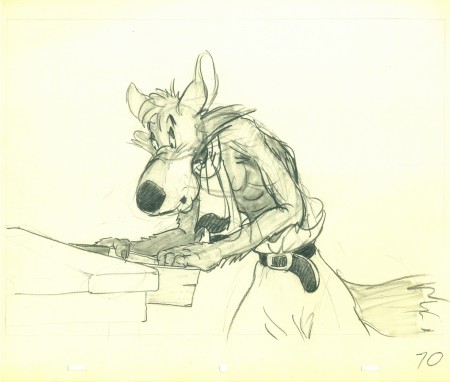

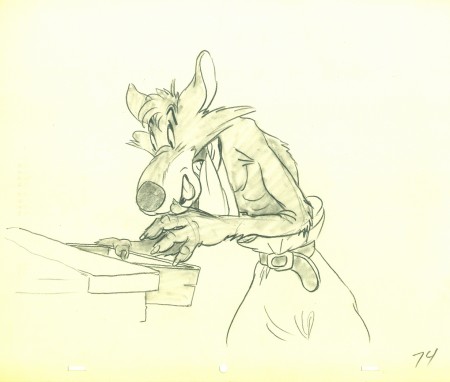

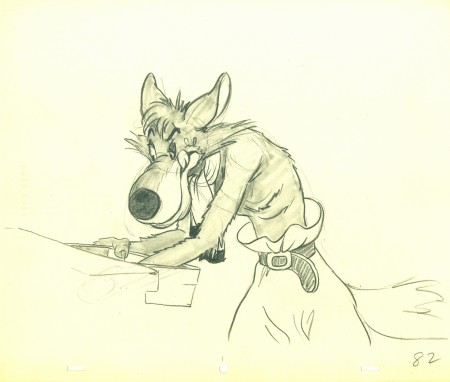

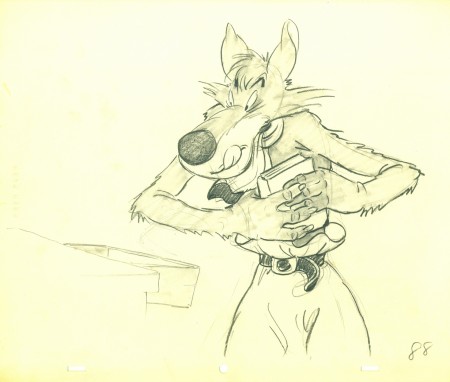

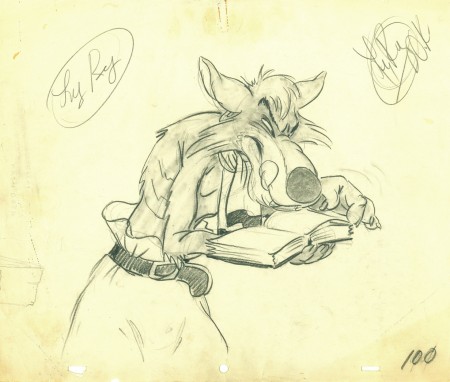

- With all the recent thought and posts on Bill Tytla, I couldn’t resist revisiting this artwork from the Harman-Ising short, The Hungry Wolf. So here it is.

We’ve seen that Tytla veered his animation style completely toward the “Method” and there is no doubt that he carried that with him even after he left the Disney studio. Unfortunately, he went to the lowest of the low and couldn’t survive any longer as an animator. He turned to direction and had to adapt his use of Stanislavsky to his directing technique.

We’ve seen that Tytla veered his animation style completely toward the “Method” and there is no doubt that he carried that with him even after he left the Disney studio. Unfortunately, he went to the lowest of the low and couldn’t survive any longer as an animator. He turned to direction and had to adapt his use of Stanislavsky to his directing technique.

Unfortunately, the “actors” he was given weren’t up to the task. Those “actors” were the least of the animation industry, those who had learned a lot of bad techniques, ways of cheating and a lack of a deep interest in bringing the souls of his characters to life.

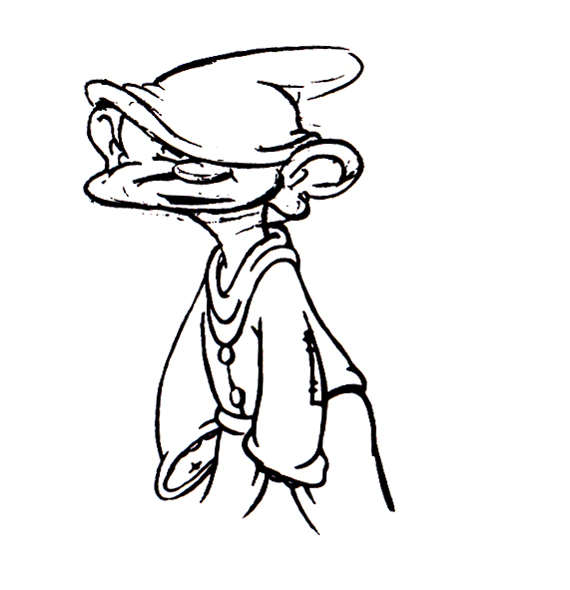

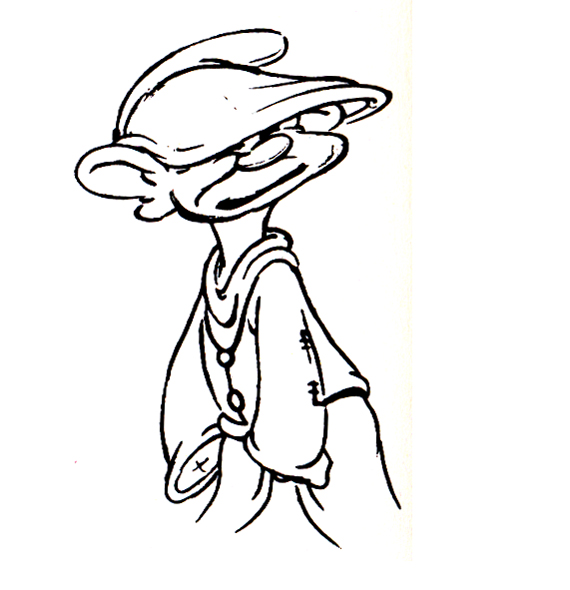

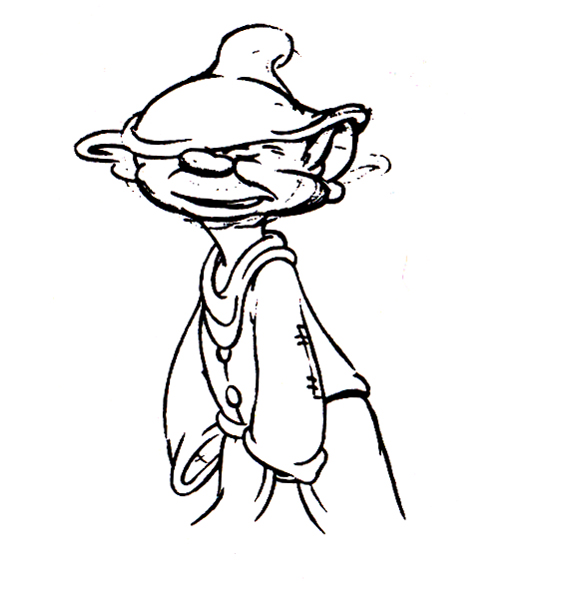

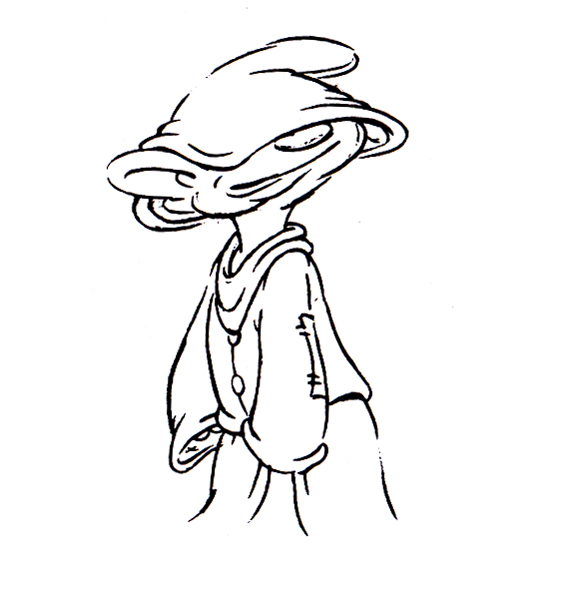

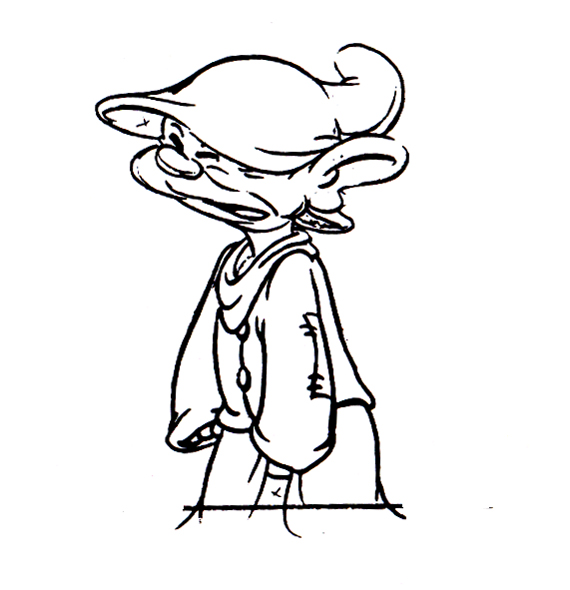

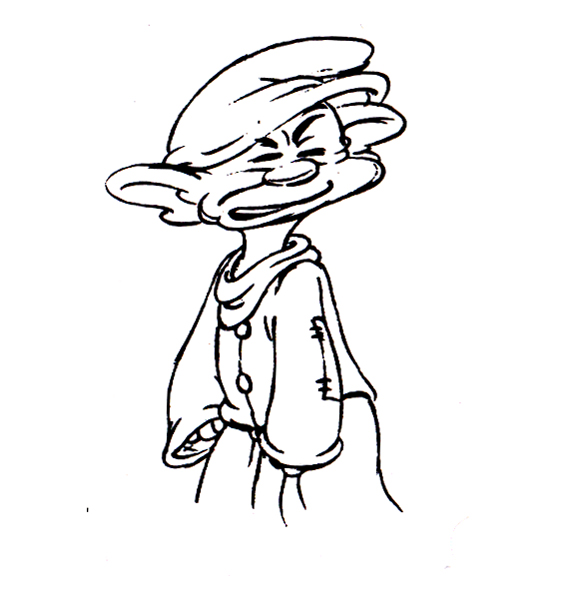

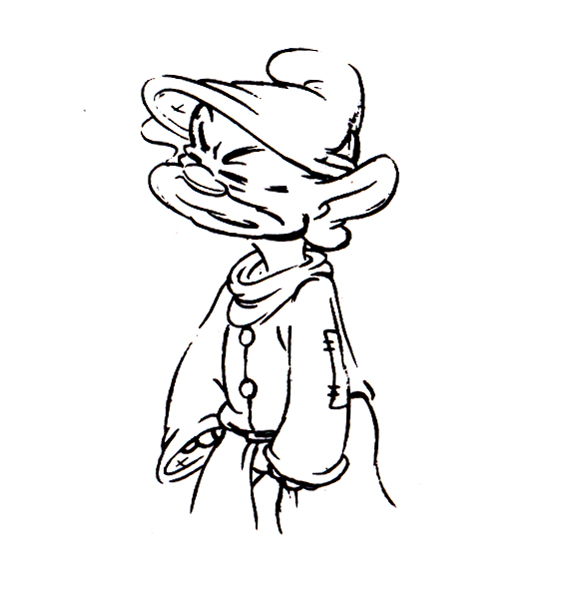

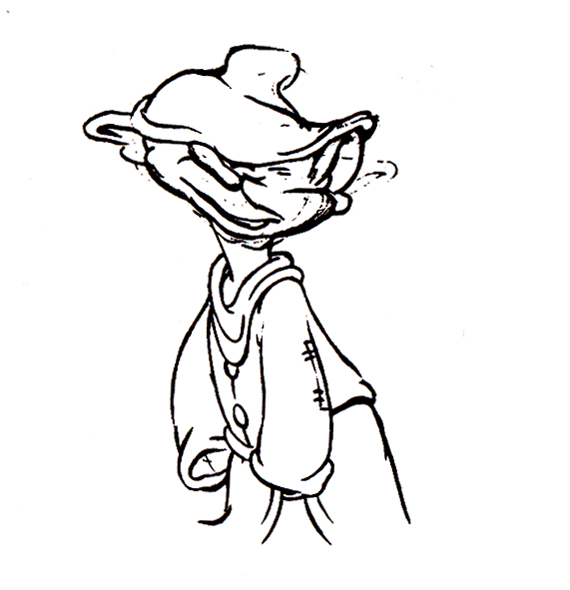

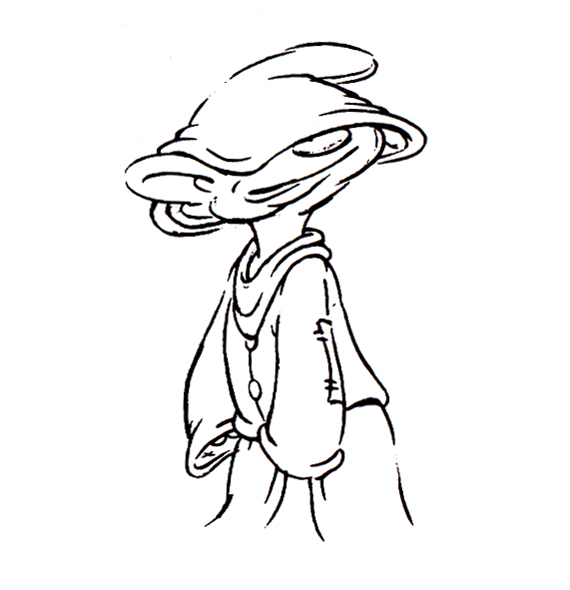

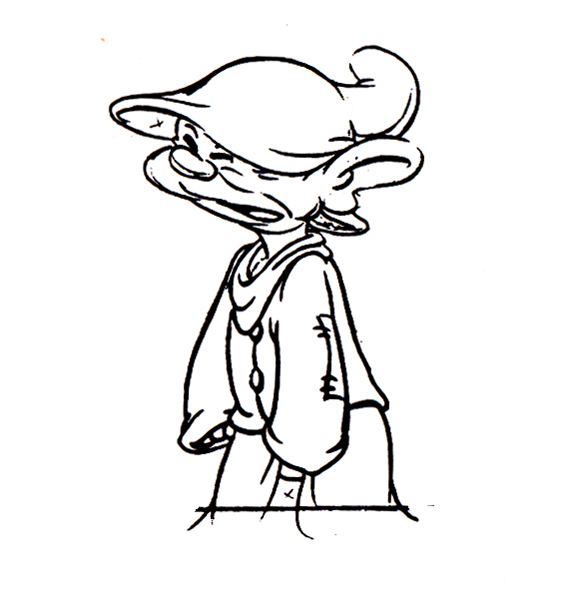

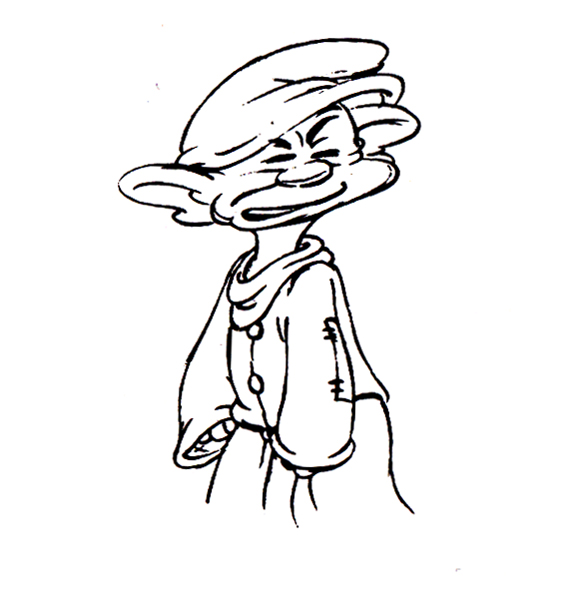

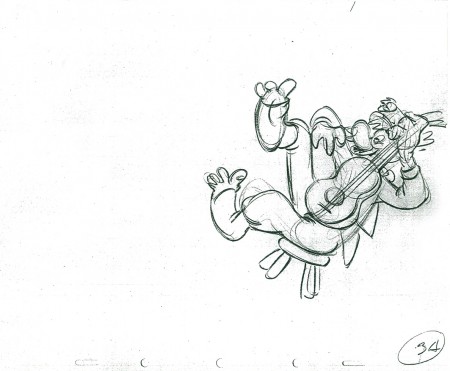

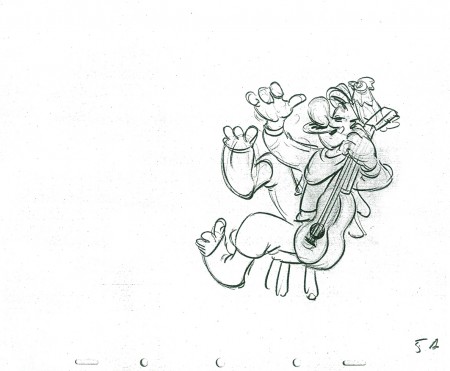

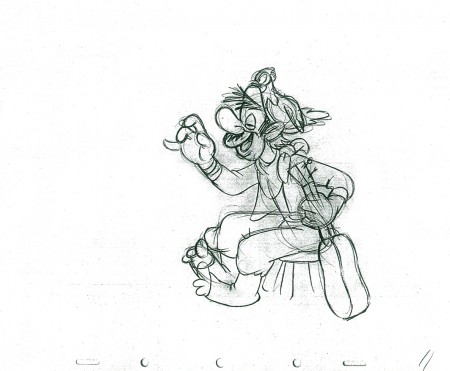

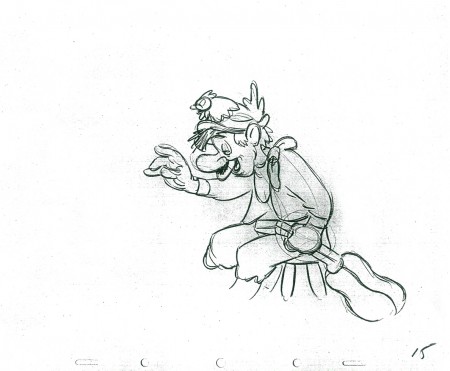

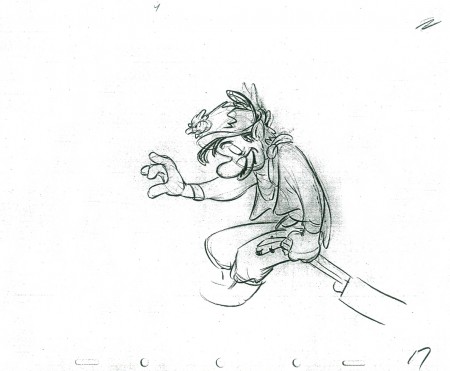

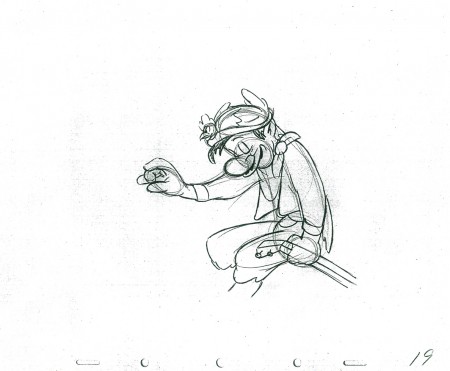

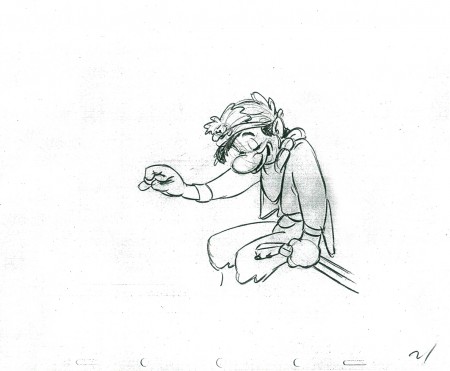

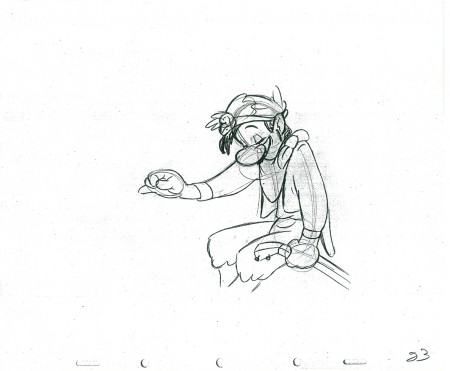

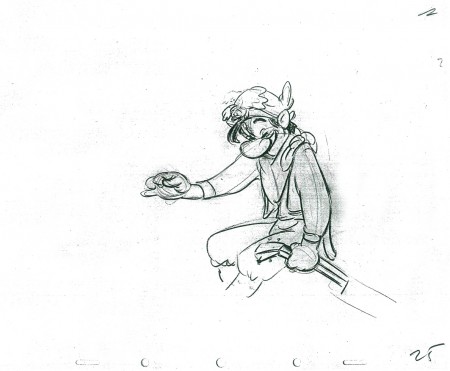

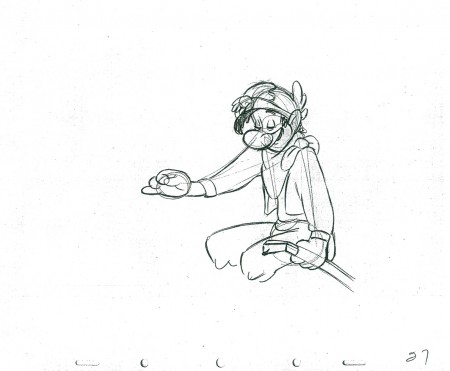

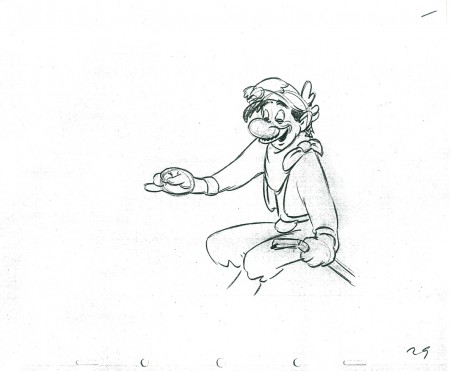

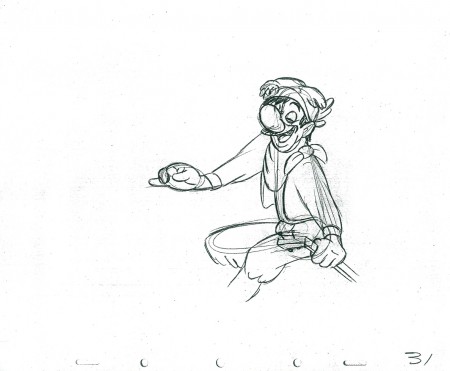

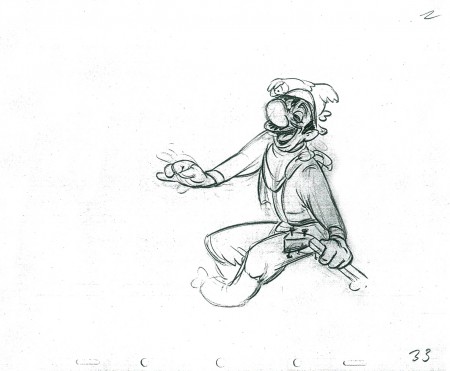

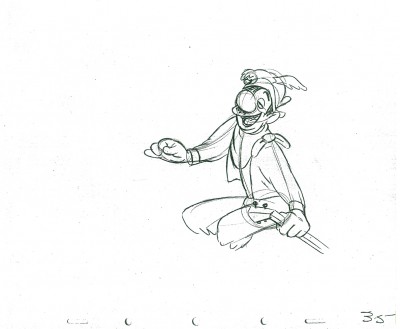

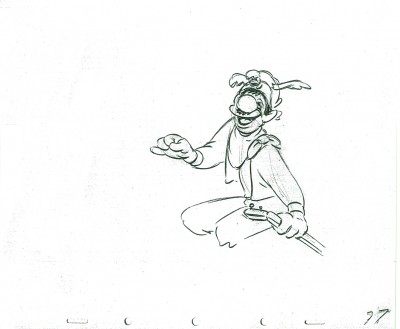

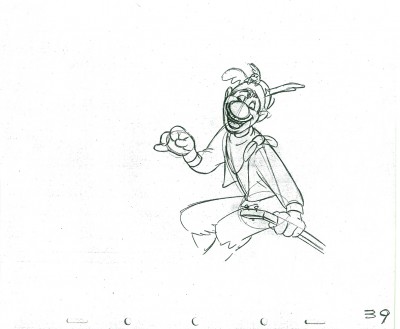

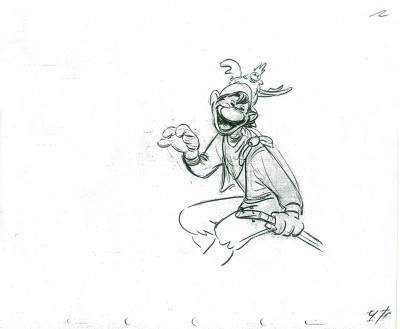

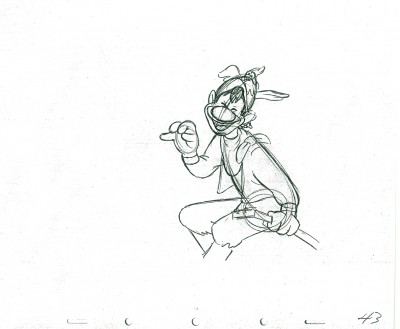

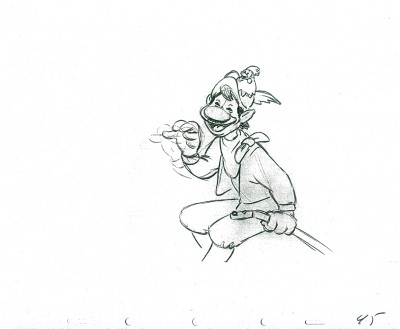

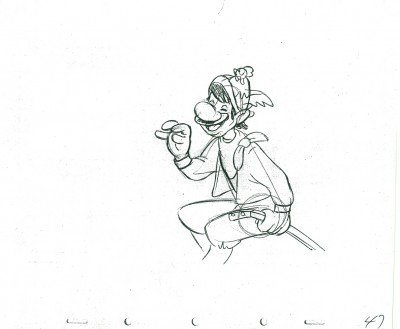

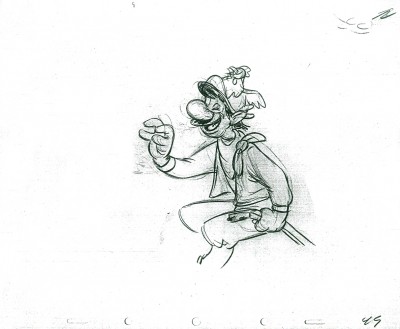

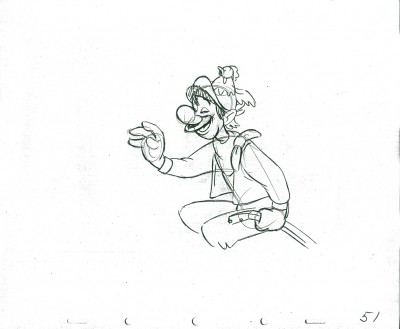

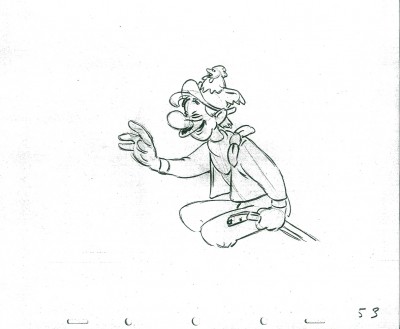

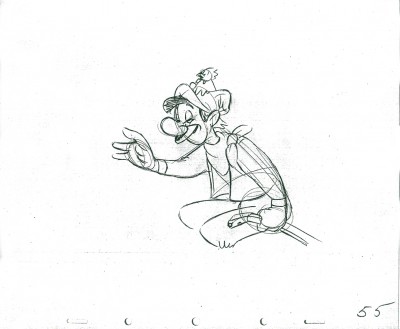

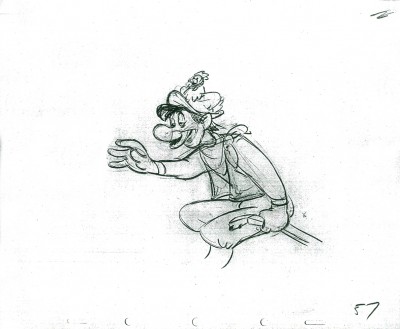

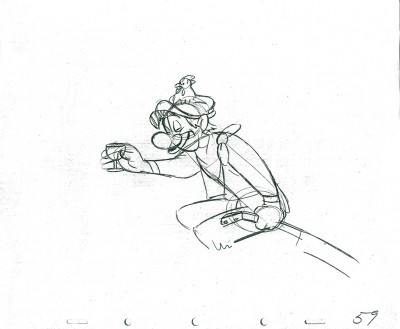

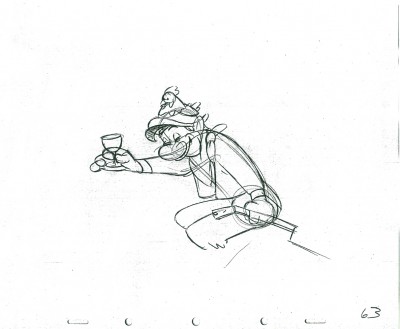

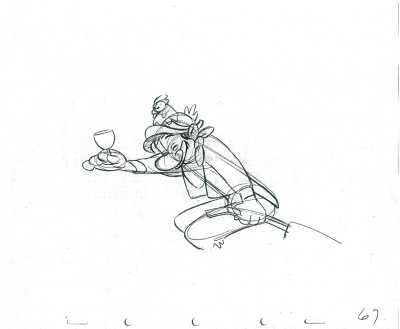

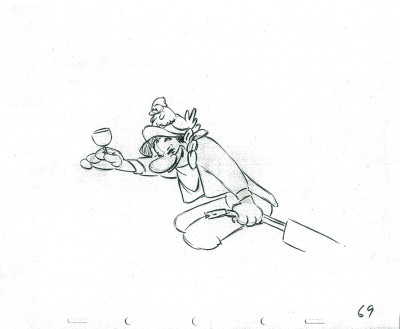

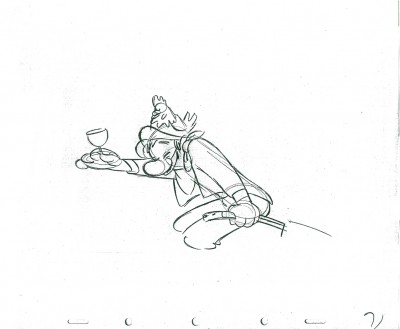

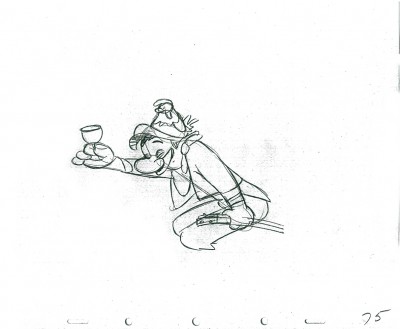

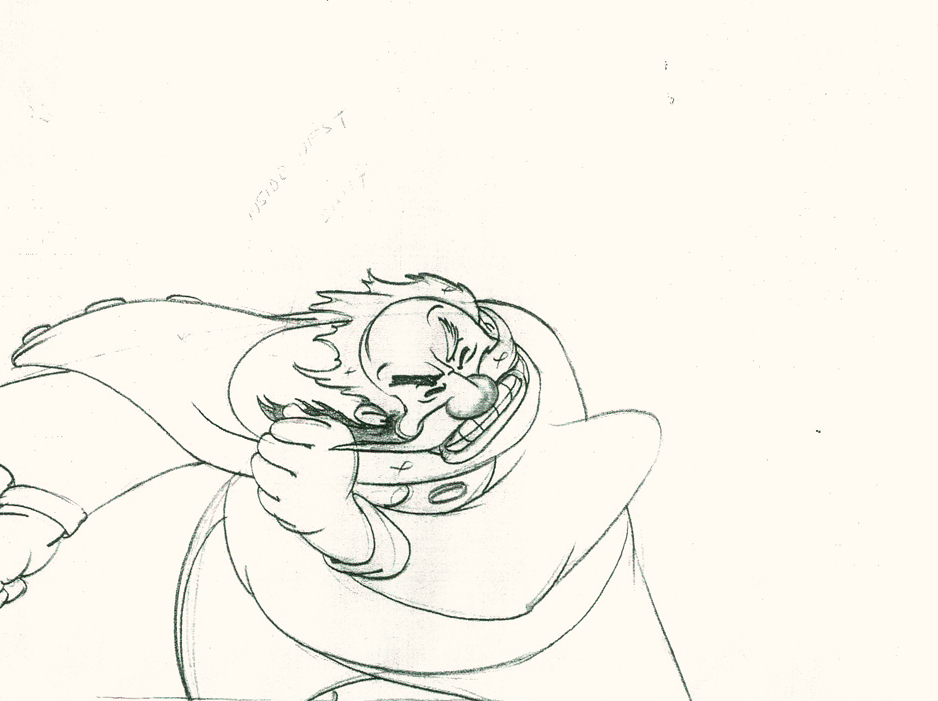

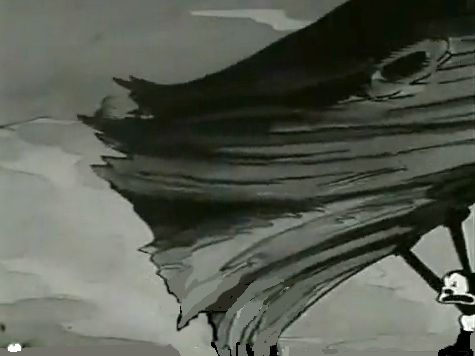

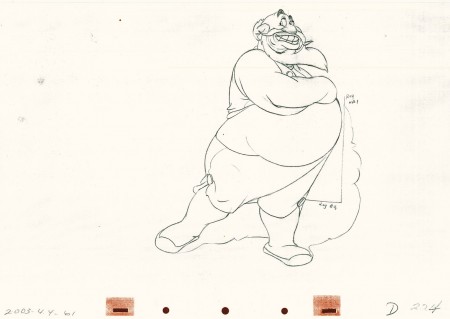

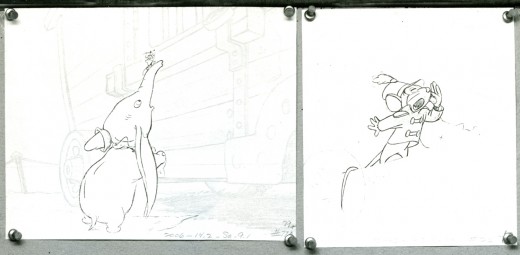

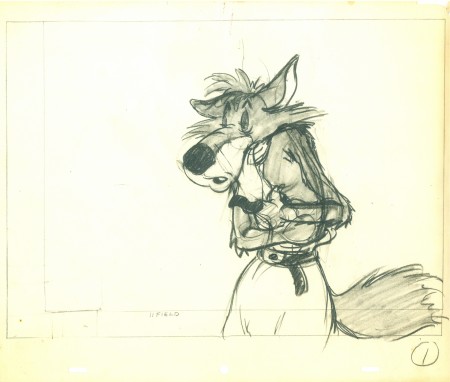

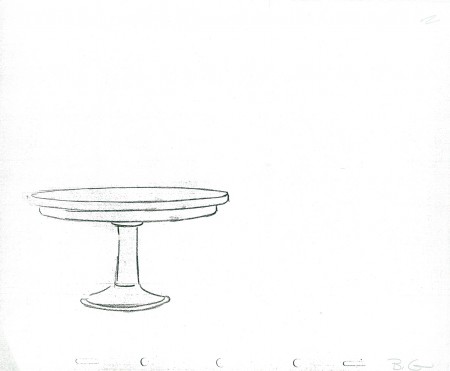

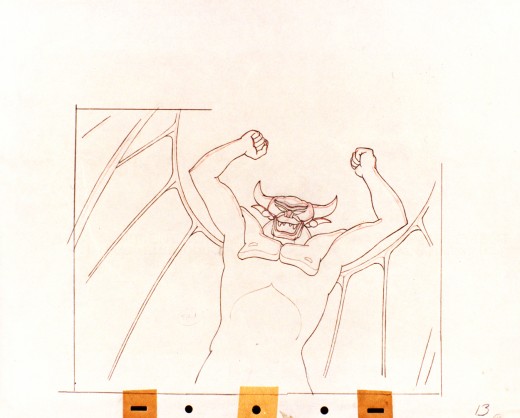

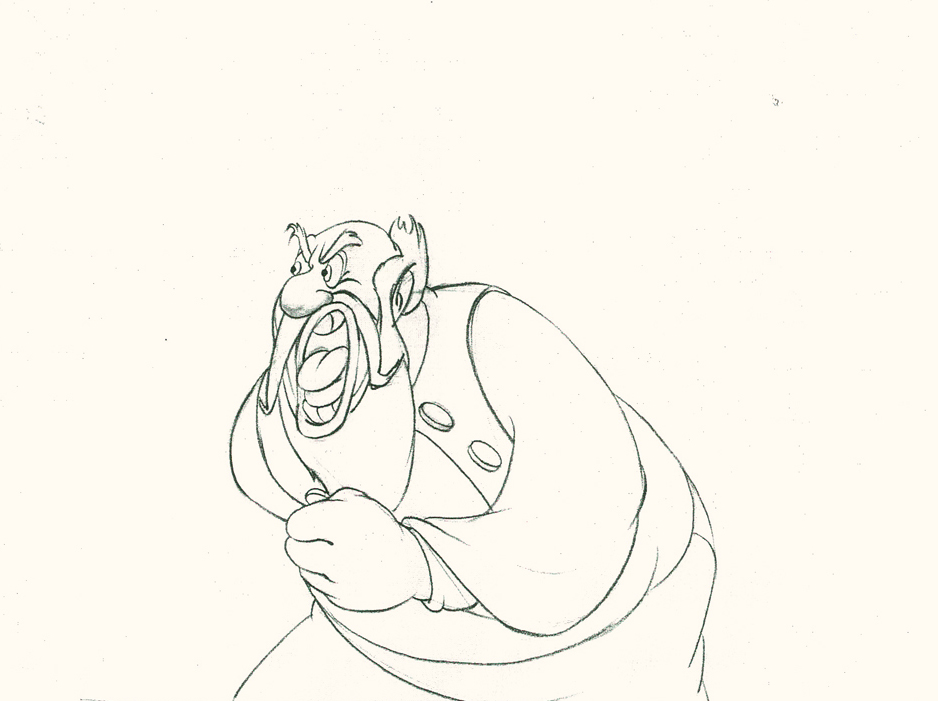

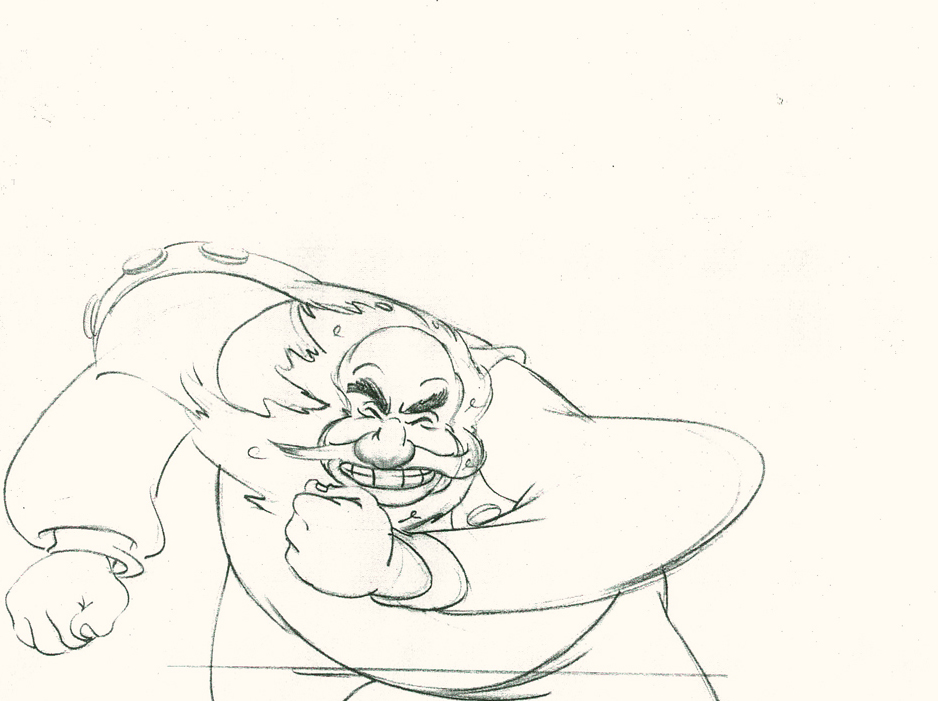

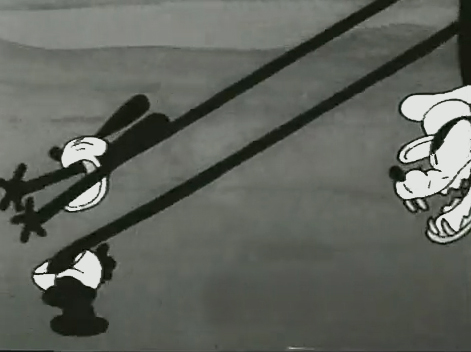

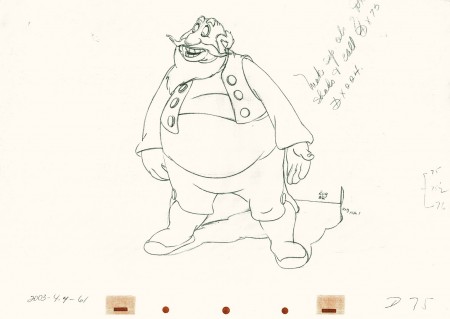

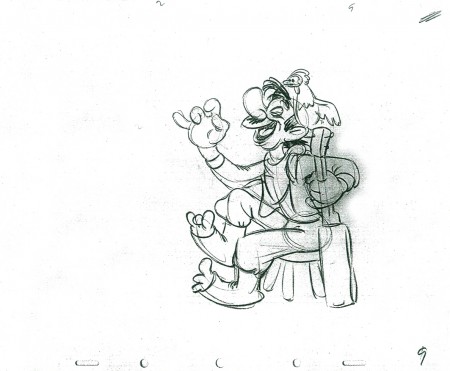

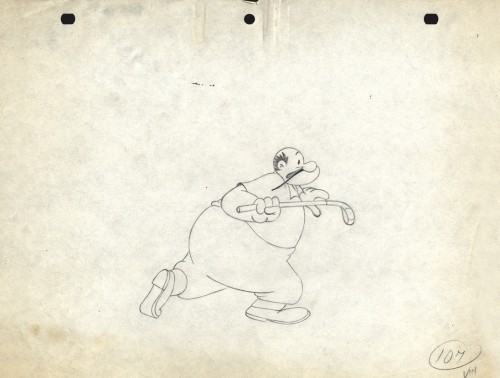

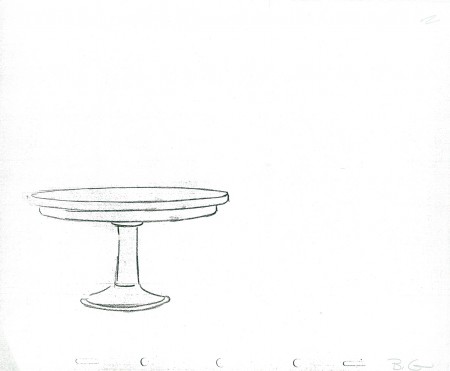

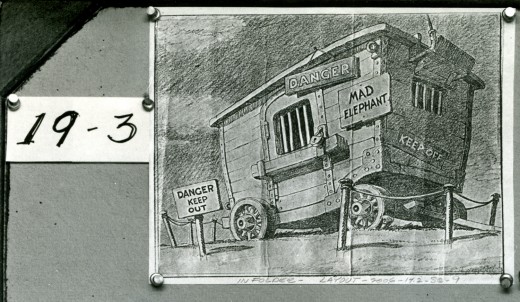

I was surprised to learn that Tytla had worked at a studio that was a bit better than Terrytoons or Paramount right after he’d left the haven of Disney. John Canemaker loaned me a cache of drawings for a Hugh Harman film, The Hungry Wolf, made in 1940 at MGM. It’s not a very good film; the drawings are signed by Tytla, but they have no ladder indication for an Assistant to do the inbetweens. Most oddly, the wolves are shaded in by Tytla. Also take note of the table being animated into place. Are these animation drawings? Is it LayOut posing to give to someone else to animate? And greatest of all, what is Tytla doing at MGM?

Since this would have been completed in early 1942, I can only assume that it was during the strike at Disney that Tytla did some work for Harman in mid 1941. Most probably he was acting as an Animation Director and NOT animating the scene. He worked under Harman, who got credit for directing.

There’s no attempt at distorting or stressing the drawings in any way. I assume the character wasn’t designed by Tytla. It’s similar to a character design that was used in other Harman films.

Here are all the drawings given me by John.

1

________________________

1

________________________.

The following is a QT of the entire scene with all the drawings included.

Since I didn’t have exposure sheets, I calculated everything on ones

(which seems to reflect the timing in the final film) and left however many drawings to the assistant and inbetweener.

Many thanks to John Canemaker for the loan of the drawings. It was great just touching them.

Action Analysis &Animation &Animation Artifacts &Commentary &Tytla 15 Apr 2013 05:25 am

Tytla Distorts – 5

- I thought it’d be a little fun to give a little showing of some of the distortion and stress Bill Tytla did on some of his drawings. He didn’t feel the need in all of his characters to actually distort and stretch the character completely out of shape as he did in a character like Stromboli.

There were times when he could use the limbs of the character and the flexibility of the movement to provide the looseness that he was searching for. Cartoon characters like the seven dwarfs or Stromboli allowed a wildness that another, such as the devil in Night on Bald Mountain offered.

Let’s just jump into it and take a look at some drawings.

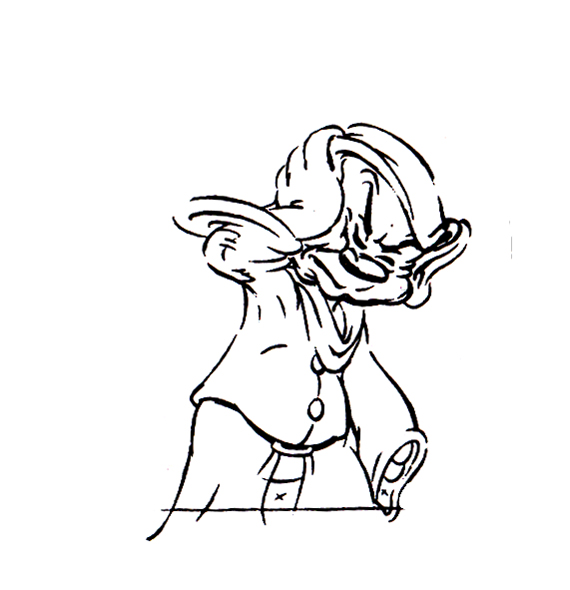

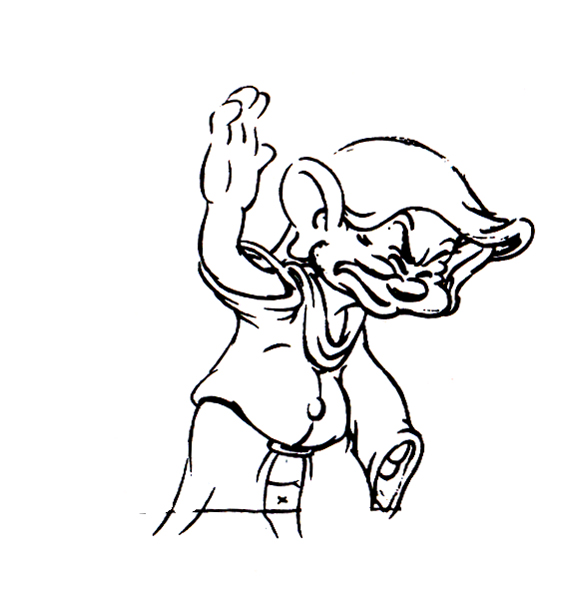

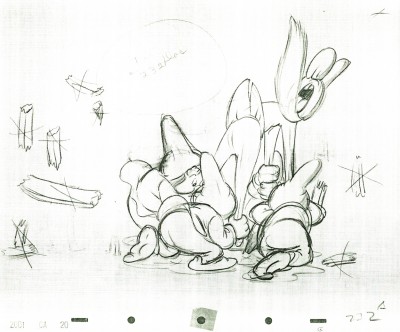

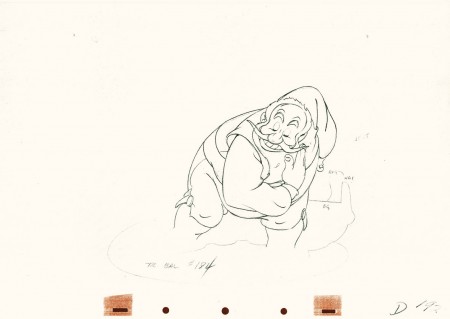

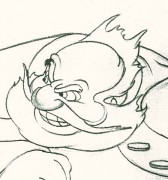

Obviously, this first one is Doc from Snow White

as he drains some water from his face:

1

1

3

3

Immediately we can see a flexibility in the jowls of Doc’s face,

and Tytla has plenty of fun with it.

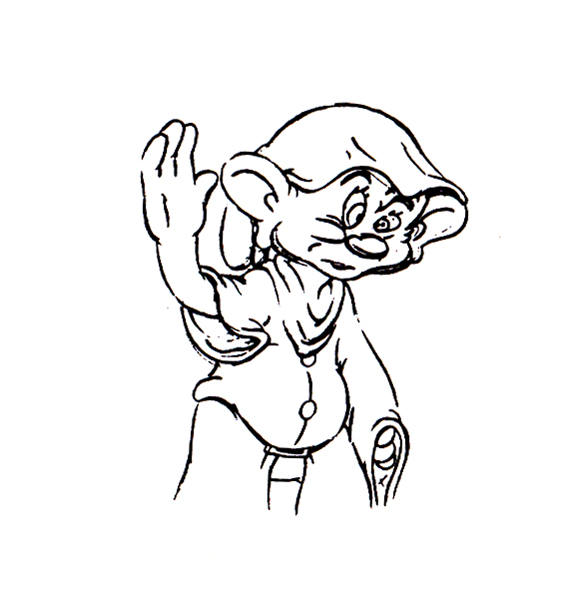

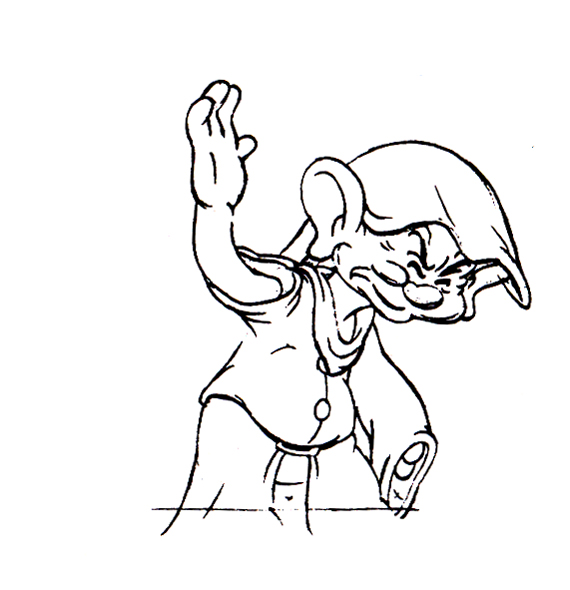

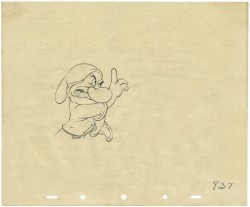

Now here’s a similar thing with Dopey shaking the water out of his head.

1

1  2

2

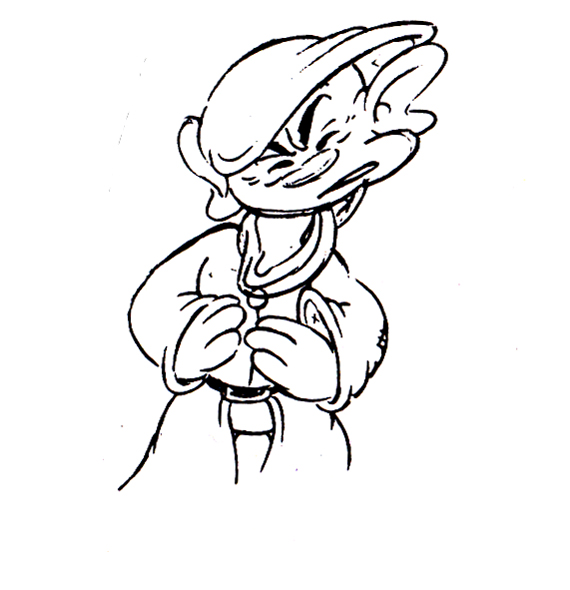

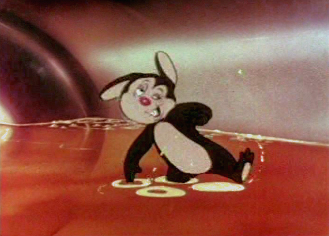

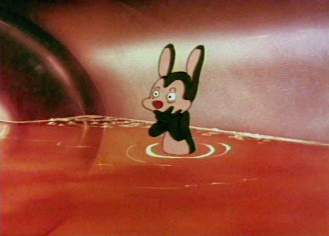

I also thought I’d pick out a nice frame grab or five of Tytla’s animation for a Mighty Mouse cartoon when he later went to Terrytoons.

1

1

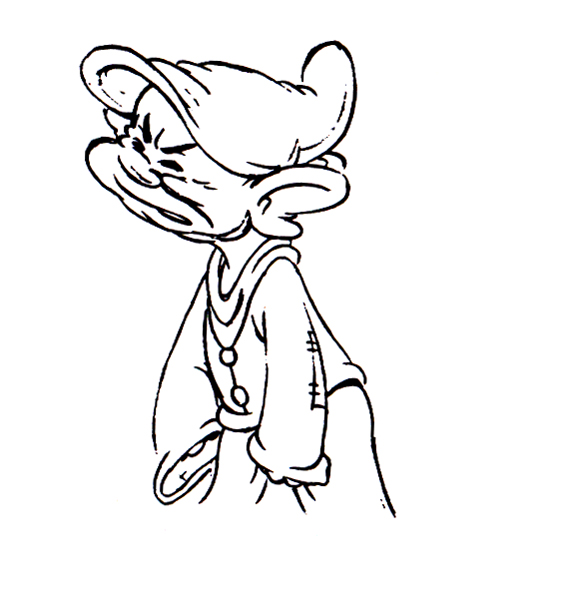

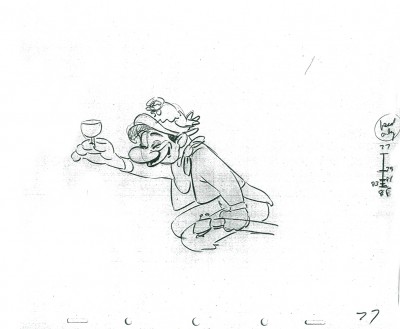

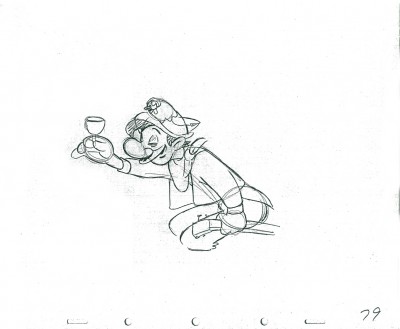

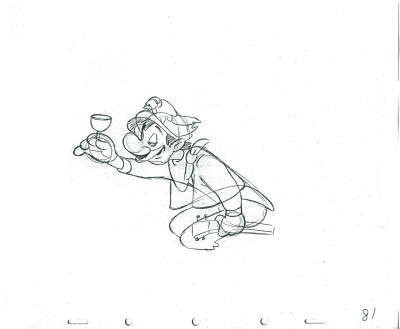

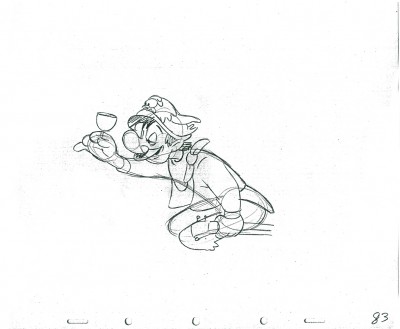

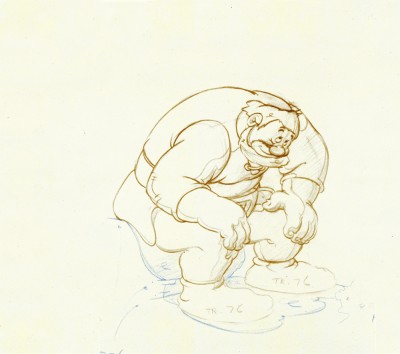

If we’re going to look at Tytla’s play on a drunk character, let’s look at this beauty of a scene. It’s from a film that was never completed, The Laughing Gauchito. This was one of the short pieces being developed during the period when the South American themed films, Saludos Amigos and Three Caballeros, were in production.

For this scene Tytla uses the rubbery feel for the face, but keeps the looseness in the character for the arms and legs. There’s quite a bit of depth he writes into the scene. The character is drinking (and a little tipsy) loses his balance and tries to regain it without spilling his drink. There’s a lot there, and it’s beautifully developed, yet still not a finished scene.

The Background

1

1  2

2

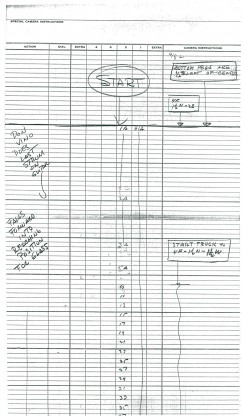

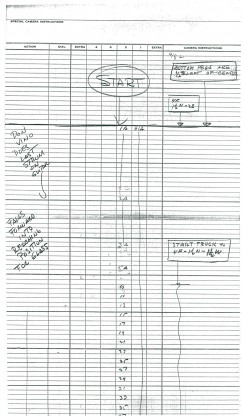

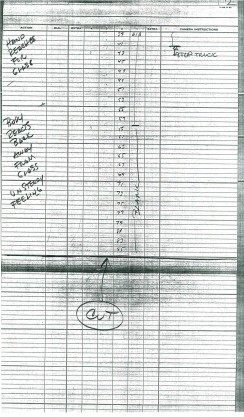

These are the X Sheets for the scene.

Here’s a QT of the scene with all the drawings included.

I strongly suggest you take a look into J.B. Kaufman‘s excellent book, South of the Border; it gives a full accounting of this film and Disney’s tour of the South American countries in preparation for the film.

Action Analysis &Animation &Animation Artifacts &Commentary &Disney &Peet &Tytla 08 Apr 2013 05:05 am

Stanislavsky, Boleslavsky and Tytla’s Smears & Distortions – 4

Boleslavski was a great admirer of Stanislavsky and his acting techniques. When he, Boleslavsky, came to the United States, he taught the Stanislavsky technique to his students. These included Lee Strasberg, Stella Adler and Harold Clurman; all were among the founding members of the Group Theater (1931–1940). The Group Theater was the first American acting ensemble to utilize Stanislavski’s techniques, and its members all went off to espouse their own versions of the “method.” American acting had taken some real turns into the creation and development of a true system for getting the best performance out of the actor.

In animation, there was animation technique and styles. These rarely had anything to do with acting. However, there were a number of animators at the Disney studio who wanted to put the focus on their acting and actually studied Stanislavsky and Boleslavsky so that their characters would give a great performance. Tytla was certainly a leader among the animators to do this.

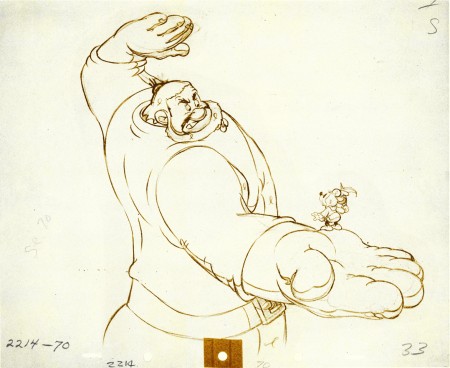

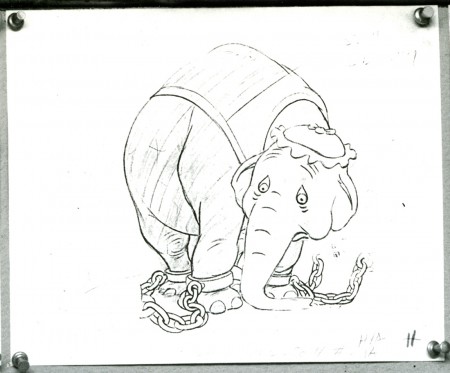

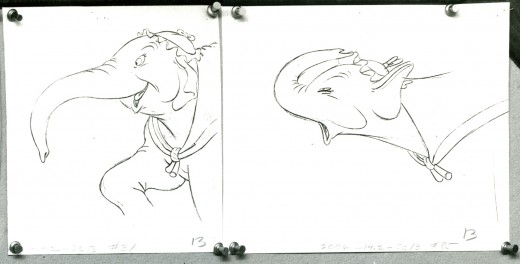

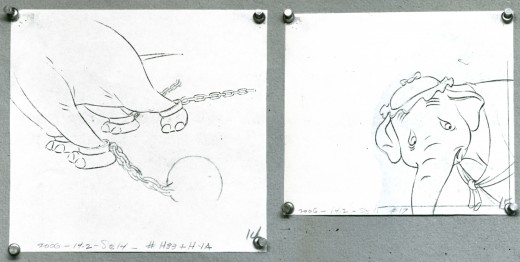

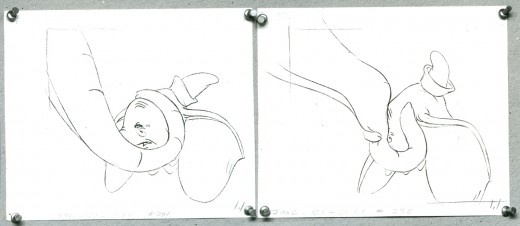

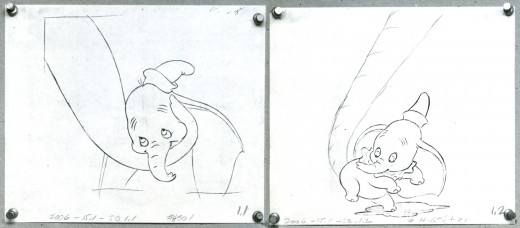

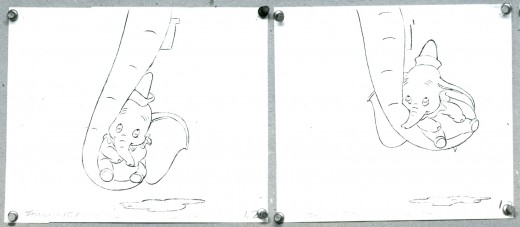

Whereas in Pinocchio, while working with such a flamboyant and

eccentric character, Tytla stretched and distorted Stromboli to

get the necessary and sudden emotional mood shifts desired.

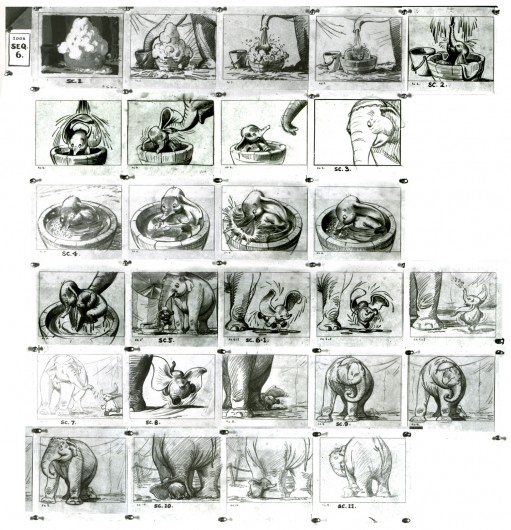

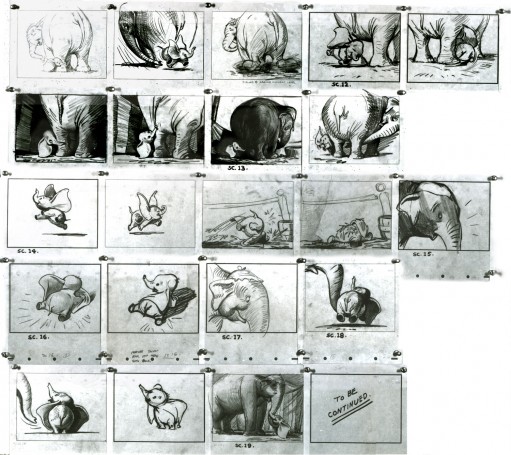

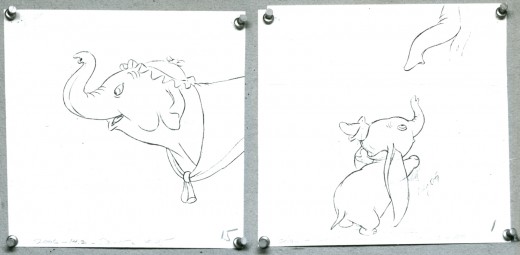

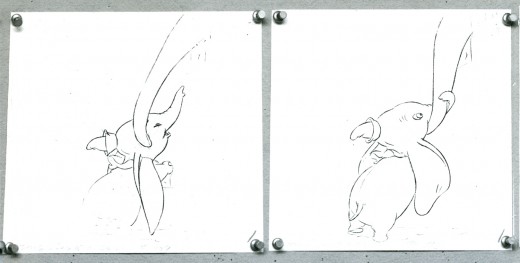

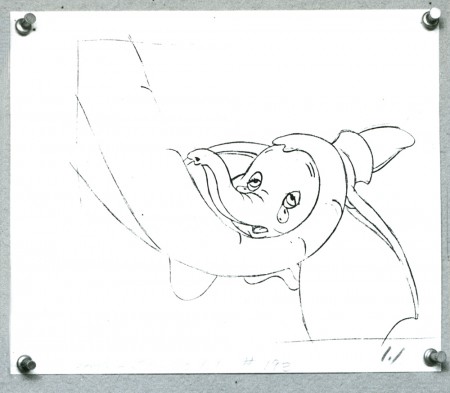

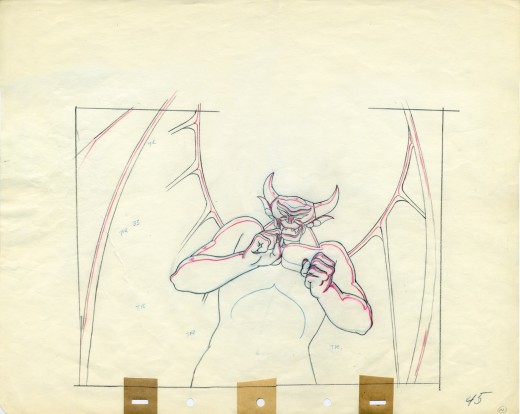

With Dumbo, Tytla modeled the character after his own son,

and he animated this scene wholly on the two characters

given to him on the strong storyboard by Bill Peet.

He didn’t use distortion, because it wasn’t the character he was animating.

Dumbo was gentle, all truth. The honest performance meant keeping everything

above board and on the table. That is undoubtedly the performance Tytla drew.

In my opinion, it has to be one of the greatest animation performances

ever drawn for a film. It’s quite extraordinary and cannot be undercut

in any possible way.

(Click any image to enlarge.)

You can see that Bill Peet’s storyboard was certainly an inspiration,

at the least, for Tytla to follow, if not to equal.

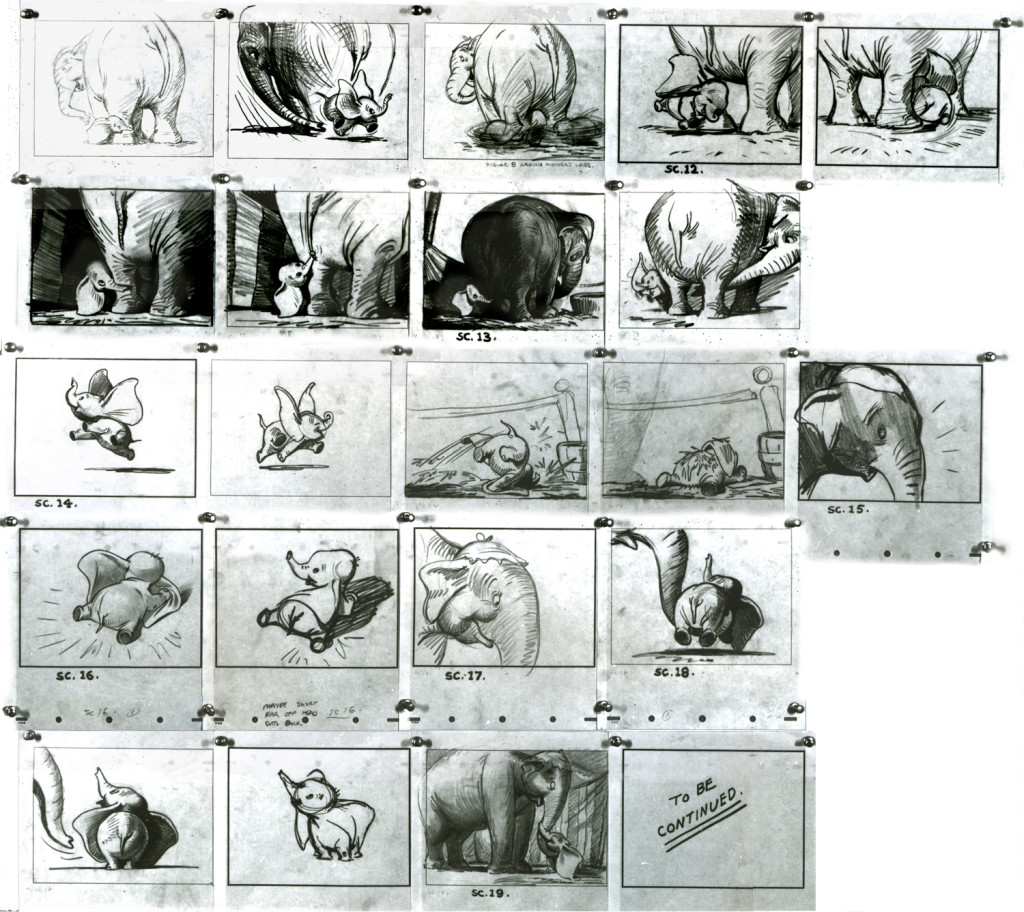

Let’s move to another film. Fantasia.

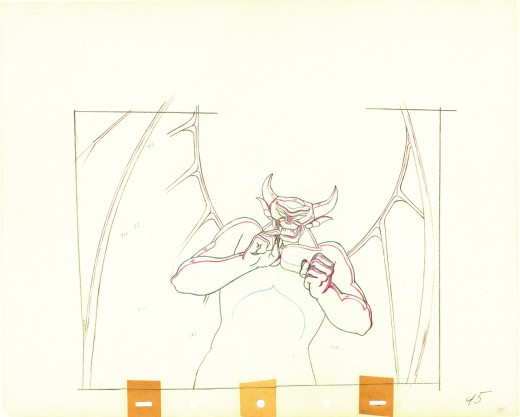

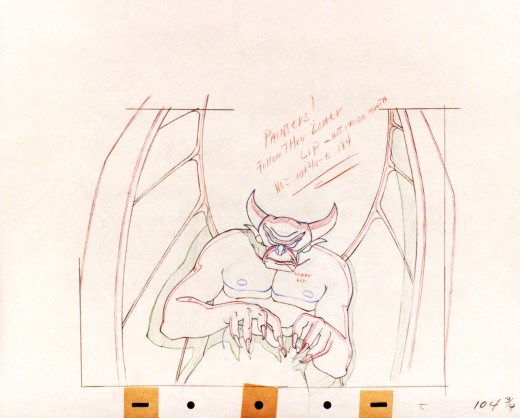

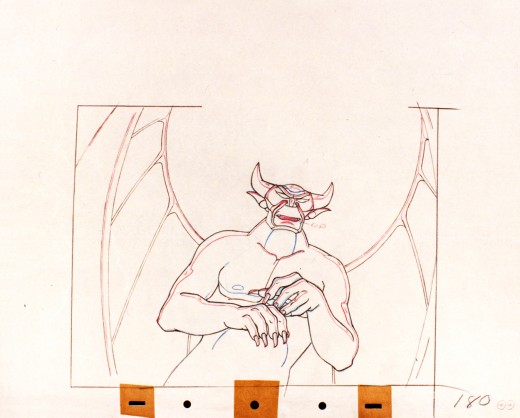

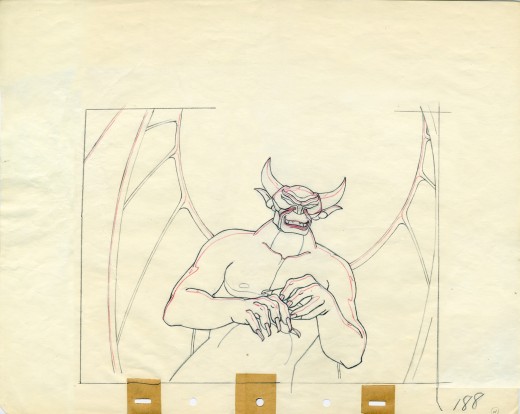

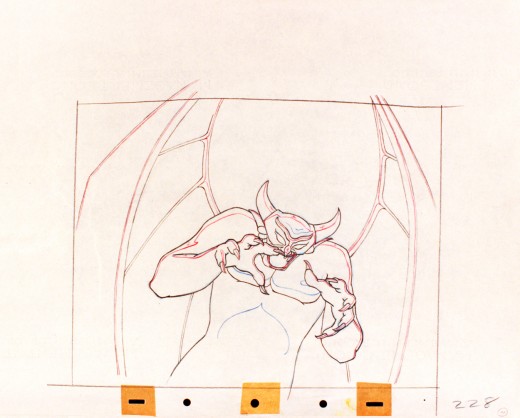

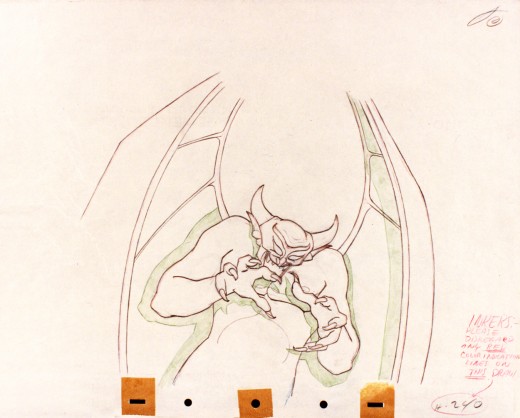

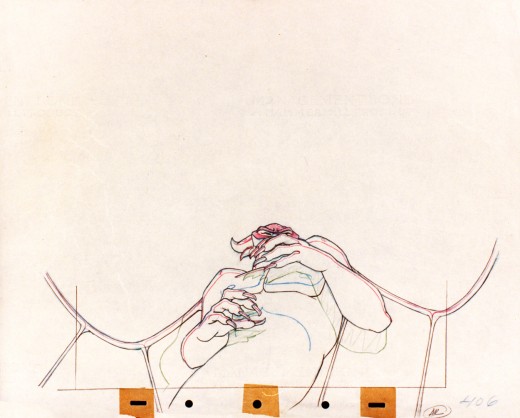

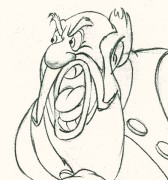

Vladimir Tytla worked on the devil in Mussorgsky’s – Night On Bald Mountain.

Here are some drawings for the scene. They’re part Tytla and part clean up by his assistant.

A good example of a Tytla drawing.

They’re pretty damned impressive drawings. If there is any distortion,

it comes from making a body builder’s shape stronger. There’s no violent

flexing of those muscles, just the natural thing on display in the middle

of a dance sequence. Strong and forcefully beautiful drawings. The

distortion is done by the other spooks floating out of their graves on

the way up to their leader.

The devil’s motion throughout this piece is very slow, tightly drawn images of the devil lyrically moving through the musical phases. It’s pure dance. Any distortion is done via the tight editing that Tytla has constructed. Very close images of the hands with the flame shaped dancers moving about in tight close up as Chernobog’s large face with searing eyes closely watching the fallen creatures dancing in his hands. It’s distortion enough.

Tytla has constructed the most romantic sequence imaginable, and the emotion of the dance acts as the climax for all of Fantasia, and it succeeds in spades. All hoisted by the animation, itself. No loud crushing peak, just a dance done in a tightly choreographed number completely controlled by Tytla. It’s the ultimate tour de force of animation, and we’ll never see the likes of it again.

So essentially I’m pointing out that Tytla used distortion in the animation drawings to execute his acting theories, but as he grows, he not only uses his animation (and animation drawings) to “Act”, he uses his abilities as an Animation Director. The cutting and the movement of the scenes is used for the Acting, as well.

Action Analysis &Animation &Commentary &Tytla 01 Apr 2013 04:55 am

Stanislavsky Boleslavsky and Tytla’s Smears & Distortions – 4

I would guess an actor, one who was truly devoted to their craft, would try to assume the full personality of the character he or she is playing. For an actor who felt devoted to the craft, they’d veer toward some specific acting school. Stanislavski or Boleslavsky, Actor’s Studio, Meisner, Chekhov or whatever combination thereof, the actor would use these schools of approach trying to fully possess the soul of the character.

I would guess an actor, one who was truly devoted to their craft, would try to assume the full personality of the character he or she is playing. For an actor who felt devoted to the craft, they’d veer toward some specific acting school. Stanislavski or Boleslavsky, Actor’s Studio, Meisner, Chekhov or whatever combination thereof, the actor would use these schools of approach trying to fully possess the soul of the character.

Marlon Brando, Julie Harris, Paul Newman, John Garfield, Clifford Odets, Montgomery Clift and Marilyn Monroe all these acting greats had their techniques, and all those methods did start with Stanislavsky.

The question for us is how did this affect animation’s actors – the animators? Or did it? I’ve only seen this discussed in depth in one book, Mike Barrier‘s Hollywood Cartoons. Barrier shows a real understanding of Stanislavsky and Boleslavsky when he discusses the overt course of action taken by one animator, in particular, Bill Tytla.

We know that there were plenty of others that were excited by the newly discovered techniques, though we don’t know how wide spread this influence was. My first realization that it was a strong influence came from a joke John Hubley shared with me. He said that the animators broke into two groups, those that were interested in Stanislavsky and those that couldn’t spell it. Hubley was friends with Tytla. Tytla had been the close roommate to Art Babbitt, and Babbitt was close with Hubley, right to the near end.

But Tytla. Let’s look into what he was doing with his animation. I’m going to make a lot of suppositions to tell you what I think he believed . . . the reasoning and the way he worked.

Now, let me show you something.

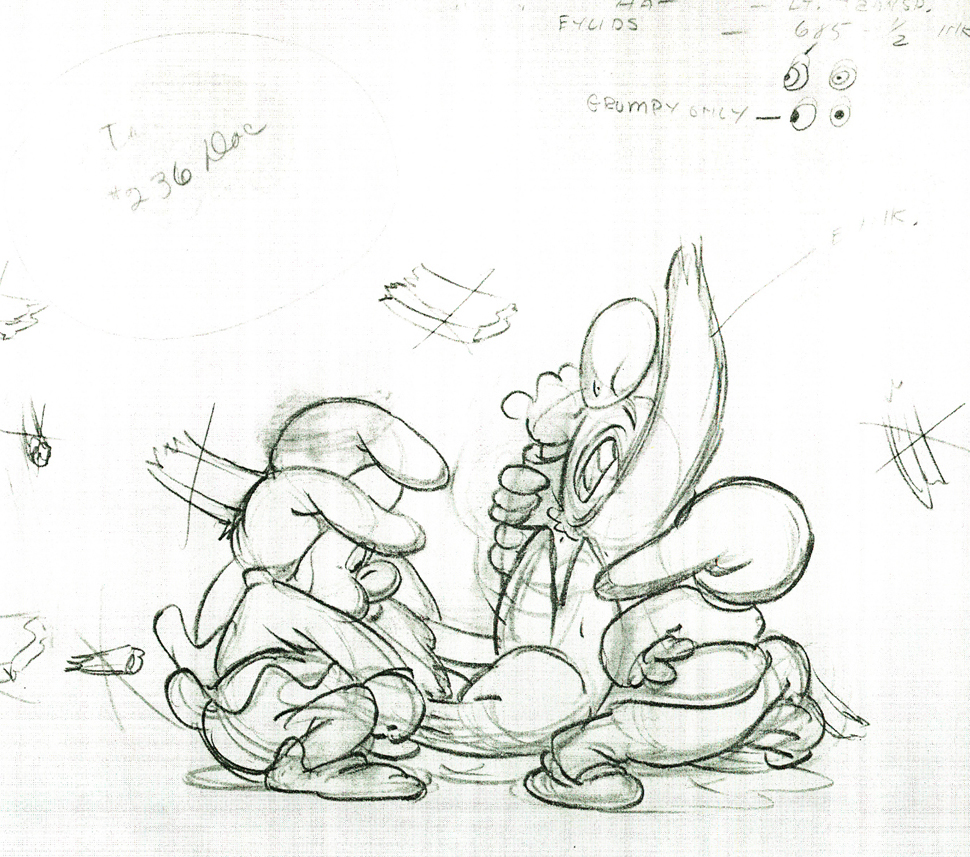

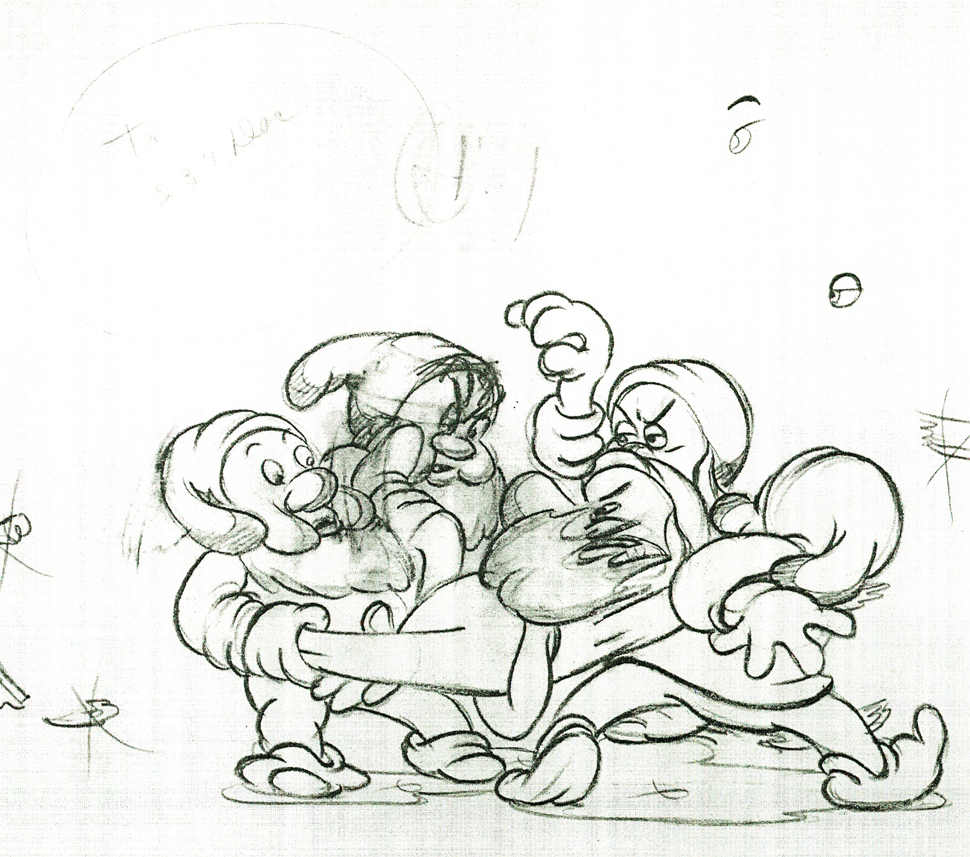

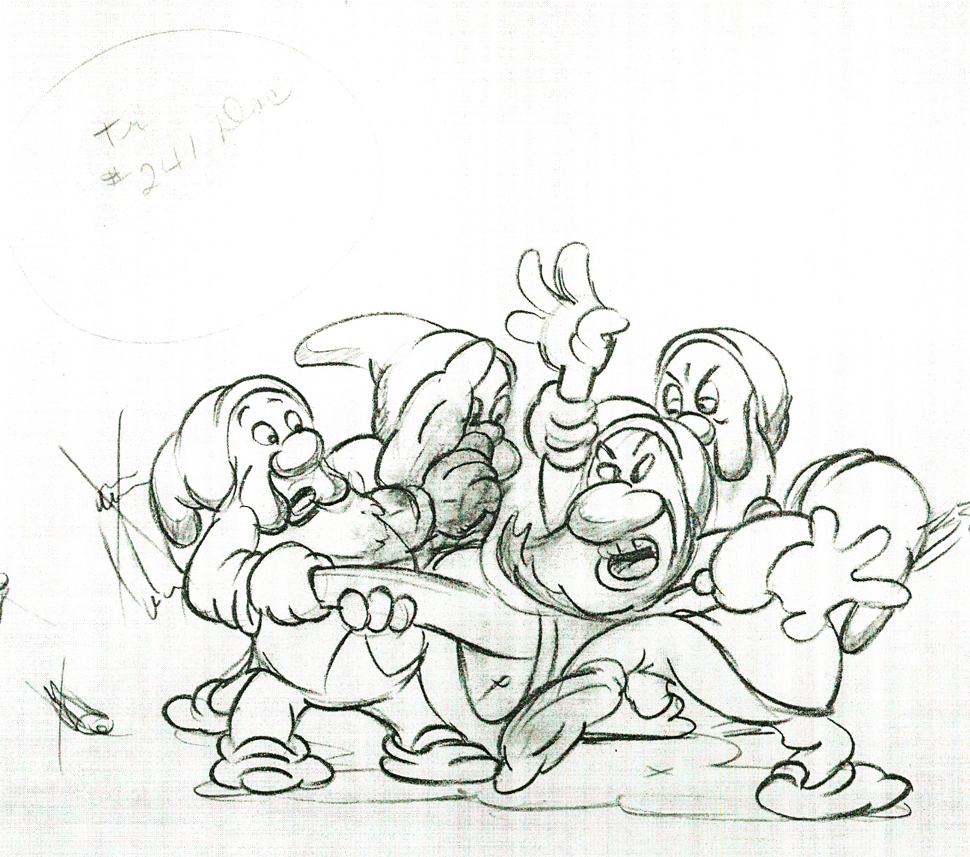

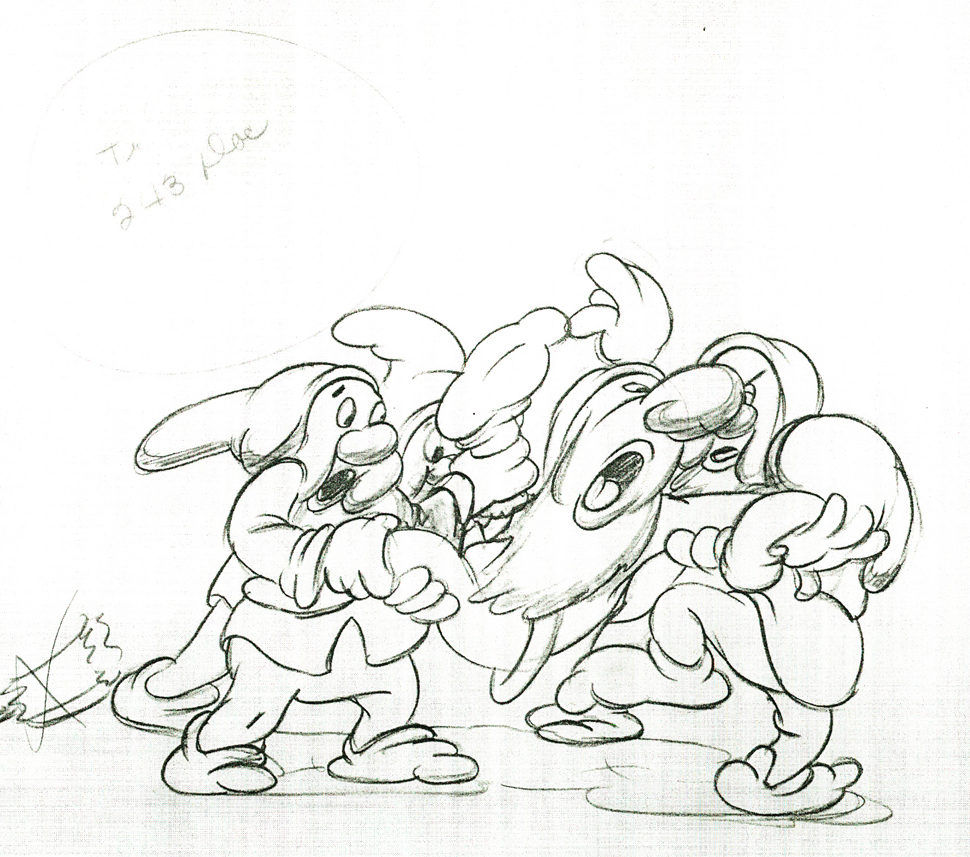

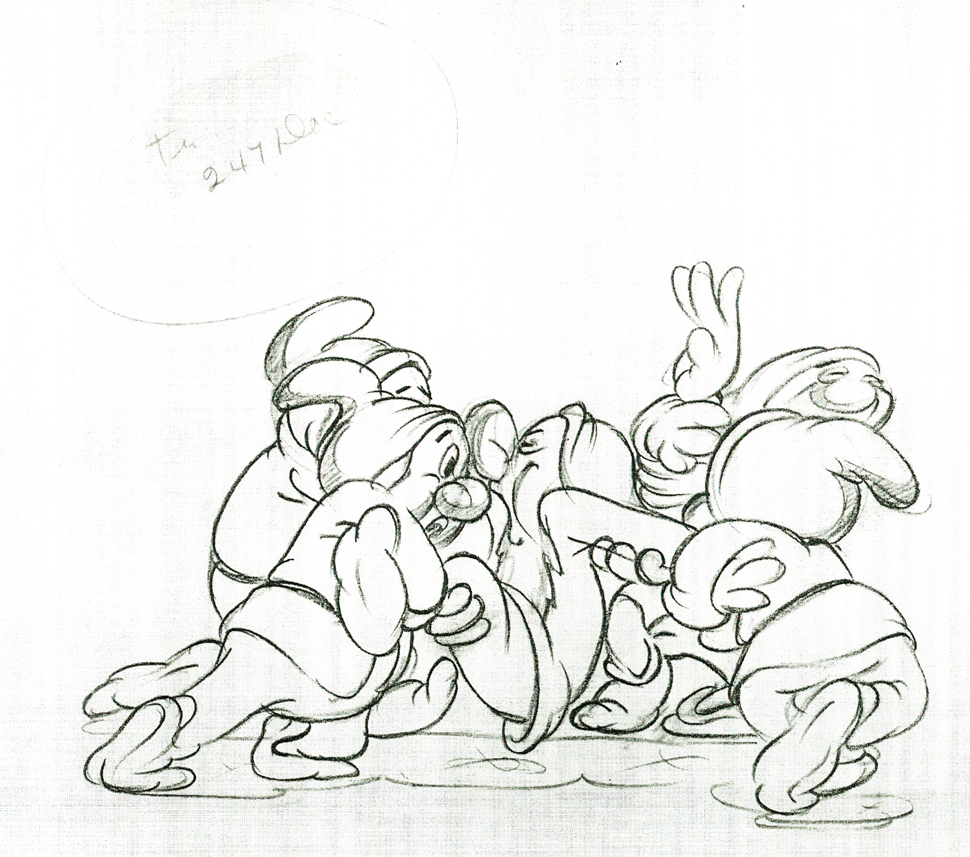

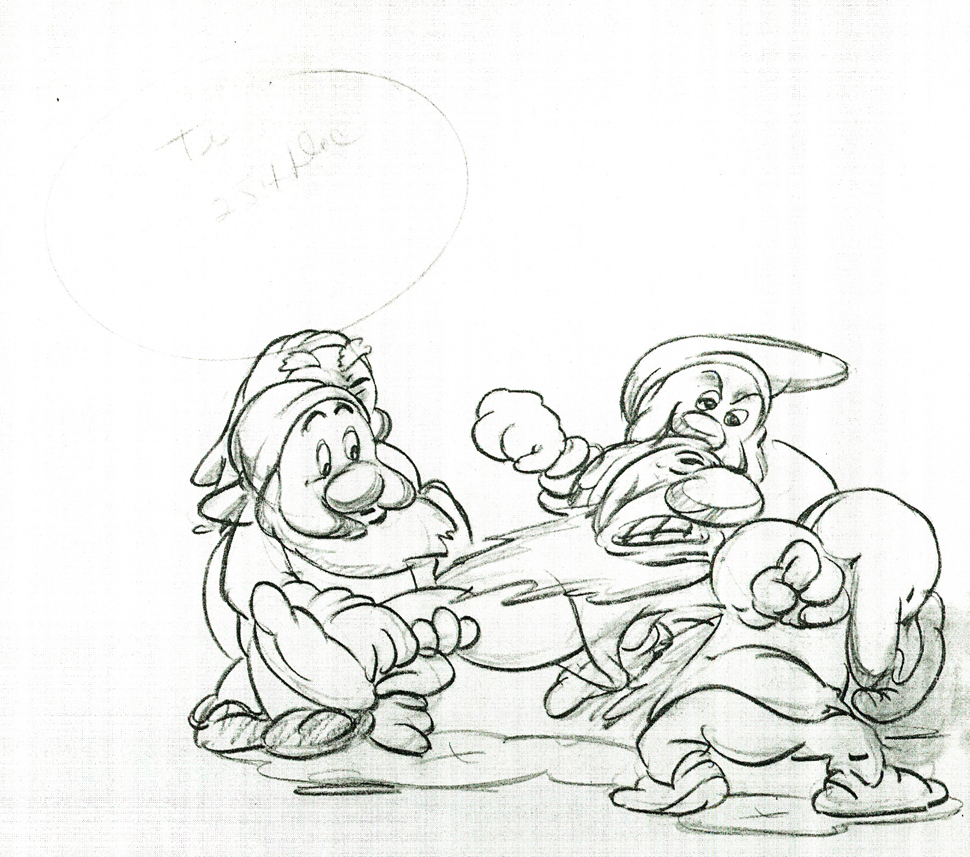

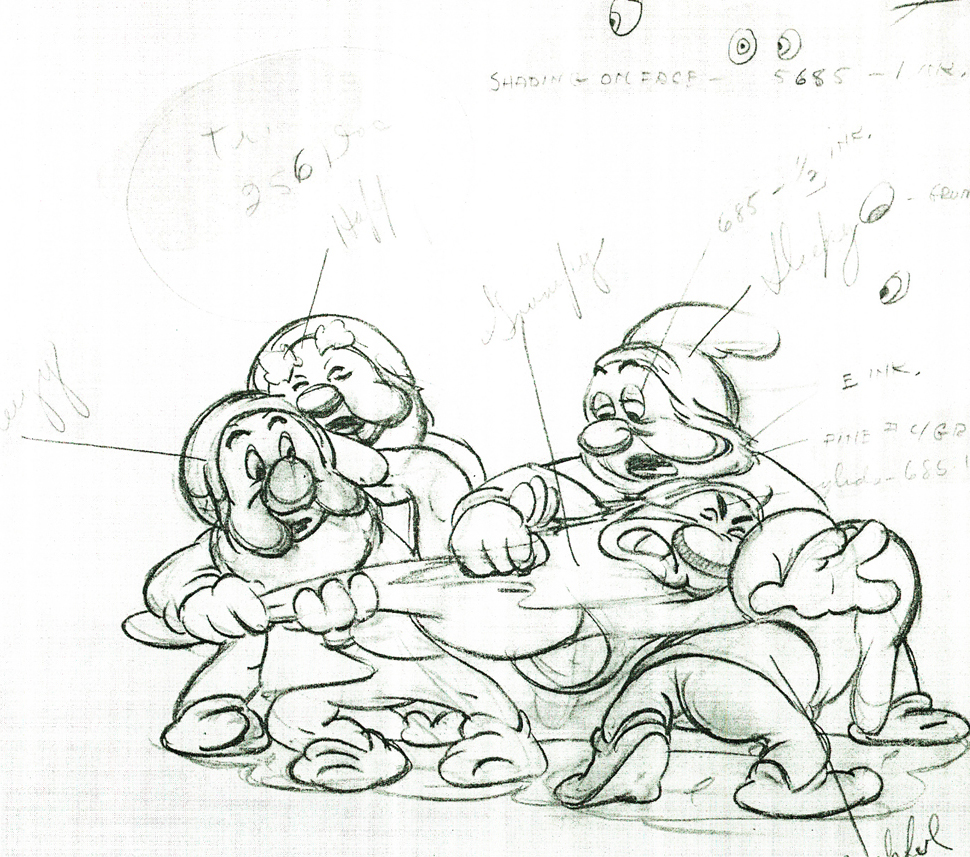

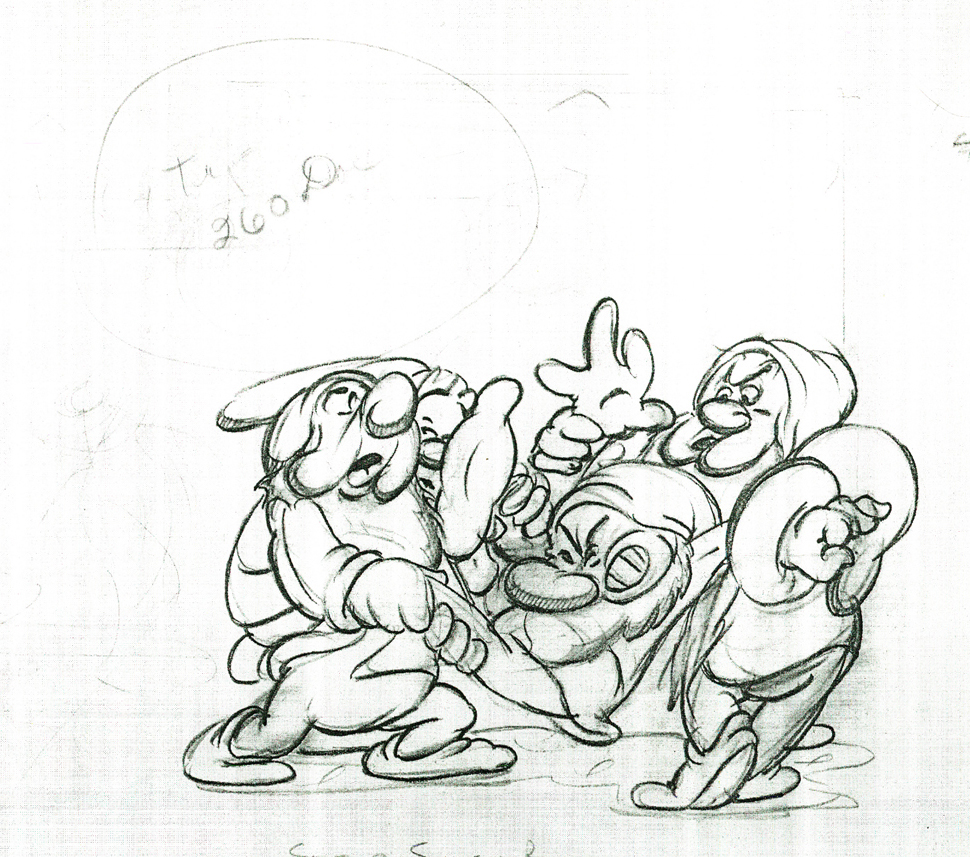

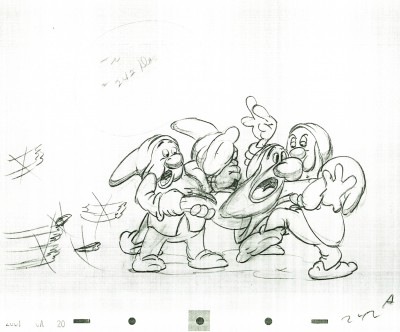

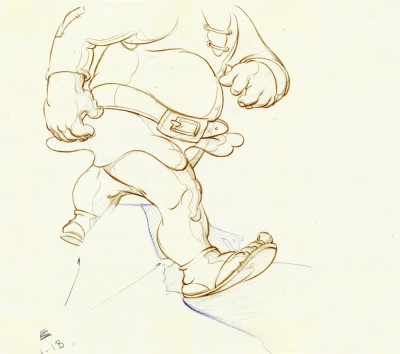

Here are some drawings and a QT movie of the seven dwarfs. Six of them are carrying Grumpy to the wash basin to clean him despite his violent protests.

Note the distortion on many of the drawings. #239 & 241 for example. #254 & 256 as well.

222

222

Here’s the QT movie of the full scene:

The P.T. is exposed on ones at 24FPS.

Note the buttons on the bottom far right will allow you to

advance (and reverse) the action one frame at a time. You

should go through this to see the distortion on the inbetweens

and how it works when the animation is in full motion.

There’s a great deal of distortion and smearing in Tytla’s work. I think he uses it to heighten the acting moments that his characters are performing. This particular scene is more action than acting, so other than to show off his distorting the characters, it isn’t a great example of acting, per se. Bt that drawing #239 is a good example of what he’ll do, even to the face of the principal character in the scene, to get his animation to work.

It’s almost as if he’d studied live action frame by frame and represents all those motion blurs in live action by smearing the face. The dwarfs are probably the first time complicated acting is successfully achieved. They’d done it before with many of the characters in the Silly Symphonies, but these are characters who sustain strong personalities over a long period of film. They also go through strong emotional changes which underline and works off their personalities.

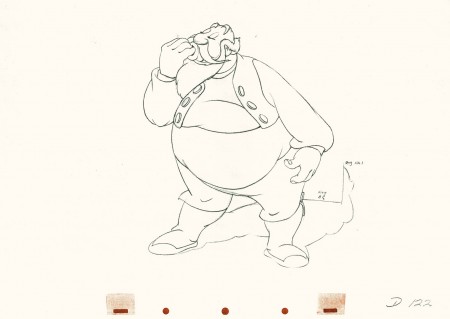

Tytla had a very different character in Stromboli for Pinocchio. He was a theatrical type, very changeable personality with emotions going all over the place – from high to low in the bat of an eye.

Tytla brought beautiful distortion to many of the drawings he did, using it as a way to hammer home some of the emotions in the elasticity he was creating. Yet, the casual observer watching this sequence in motion doesn’t ever notice that distortion yet can feel it in the strength of the motion.

Four drawings (#1, 11, 22, & 48) that shift so enormously but call no attention to itself.

Brilliant draftsmanship and use of the forms.

After I first posted some of these drawings and spoke a bit about the distortion Tytla would use to his advantage – for emotional gestures – I received some comments. I’d written that . . . “It’s part of the “animating forces instead of forms†method that Tytla used. This is found in Stromboli’s face.

This note arrived from Borge Ring after my first post Bill Tytla’s scene featuring Stromboli’s mood swing:

- The Arch devotees of Milt Kahl have tearfull misgivings about Wladimir Tytla’s magnificent language of distortions. ‘”Yes, he IS good. But he has made SO many ugly drawings”

Musicologists will know that Beethoven abhorred the music of Johan Sebastian Bach.

yukyuk

Børge

Note in one of these arms (right) Tytla uses Stromboli’s blouse to make it look like there’s distortion. It barely registers but gives strength to the arm move before it as his blouse follows through in extreme.

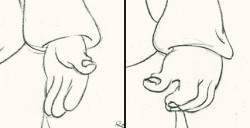

There’s also some beautiful and simple drawing throughout this piece. Stromboli is, basically, a cartoon character that caricatures reality beautifully. A predecessor to Cruella de Vil. In drawings 76 to 80 there’s a simple turn of the hand that is nicely done by some assistant. A little thing among so much bravura animation.

There’s also some beautiful and simple drawing throughout this piece. Stromboli is, basically, a cartoon character that caricatures reality beautifully. A predecessor to Cruella de Vil. In drawings 76 to 80 there’s a simple turn of the hand that is nicely done by some assistant. A little thing among so much bravura animation.

Many people don’t like the exaggerated motion of Stromboli. However, I think it’s perfectly right for the character. He’s Italian – prone to big movements. He’s a performer who, like many actors in real life, goes for the big gesture. In short his character is all there – garlic breath and all.

Here’s a short part of another scene. I’ve enlarged the images a little so that the thumbnails are more revealing. Just look at the distortion on the heads and how he stretches the arm to give it a violent emphasis.

1

1Tytla starts with arm and head all the way back to

the character’s right. It’d be hard for Stromboli to

reach any further back without real distortion.

5

5

He then slowly advances the head inbetweening slowly.

The arm hasn’t moved very much – maybe what they

call today a “moving hold.”

11

11

Now the arm comes out swiping violently.

The head’s almost complete in its turn to the left.

13

13

The arm rips across in three drawings.

The head has gone too far.

14

14

The head goes back to where it should – almost no inbetweens

for Stromboli to get ready for speech. He’s taken 14 drawings

to display his anger.

20

20

The arm comes back into a near fist; the expression is violent.

22

22

The head starts shaking in a “no” gesture.

Violent.

25

25

The head and arm are all the way back.

The vest has been set up to make a violent move.

28

28

Now the arm and fist swipe across in violence.

30

30

He’s completely pulled his angry head in to his neck.

32

32

Both arms, moving violently, are suddenly restrained.

34

34

He hits a full stop with his arm.

37

37

He’s made the realization that he has to change his expression

so that he doesn’t lose the frightened kid – completely.

Here’s the final QT of the entire scene.This part comes at the very beginning:

Stromboli

Click left side of the black bar to play.

Right side to watch single frame.

David Nethery had taken my drawings posted and synched them up to the sound track here.

It’s not clichéd, and it’s well felt and thought out. Think of the Devil in “Night on Bald Mountain” that would follow, then the simply wonderful and understated Dumbo who would follow that. Tytla was a versatile master.

We’ll continue next time with Dumbo Fantasia and other Tytla gems.

Action Analysis &Animation &Commentary &Frame Grabs &Tytla 25 Mar 2013 06:05 am

Smears, Distortions, Abstractions & Emotions – 2

- I wrote about this stylistic animation device not too long ago. I was leading up to the master, of course, Bill Tytla. He distorted things, alright, and in the way he did it, he changed animation forever, as far as I’m concerned.

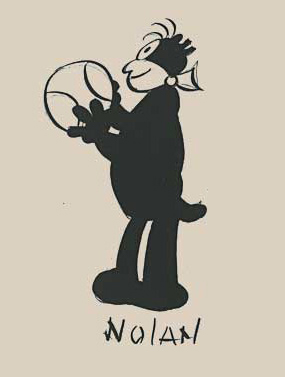

But I started that story by writing about traditional animation and where it came from and where it was going; leading to a sort of rebellion as animators started distorting things, generally, in working closely with their unconventional directors. I purposely skipped a step there, and I should go back a tiny bit and talk about a couple of animators from the silent/early sound days. Today I have Bill Nolan in my sights; tomorrow, Grim Natwick. It’s kind of important before going on to Bill Tytla.

In the animation community in 1927-1930, there were two key animators who were considered the leaders in the business:

In the animation community in 1927-1930, there were two key animators who were considered the leaders in the business:

Ub Iwerks at Disney (until he left to open his own studio) and

Bill Nolan (at first with Pat Sullivan & Felix the Cat, then with Mintz’ Krazy Kat, and then onto a series of topical gag films called “Newslaffs.”

Both were considered the fastest animators in the country, and it was debatable as to which was quicker, though Iwerks was probably the guy. When Disney learned that Iwerks was leaving, he interviewed Nolan in New York to see if he were interested in replacing Iwerks. Disney offered a high salary of $150 per week for the job. It didn’t work out; Nolan was doing an unusual series, but ultimately went to ________________Nolan’s Krazy Kat looked original.

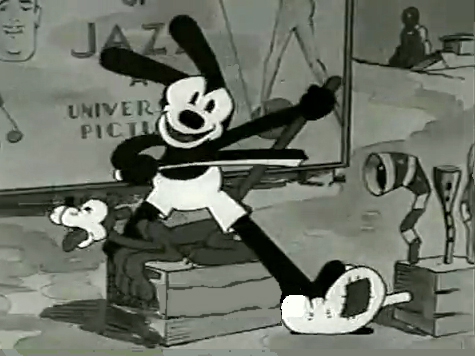

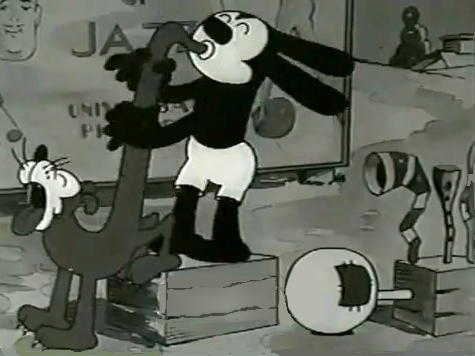

Oswald the Rabbit after Universal had taken

charge of it. Nolan just about ran the studio under Walter Lantz and allowed them to turn out an enormous amount of footage.

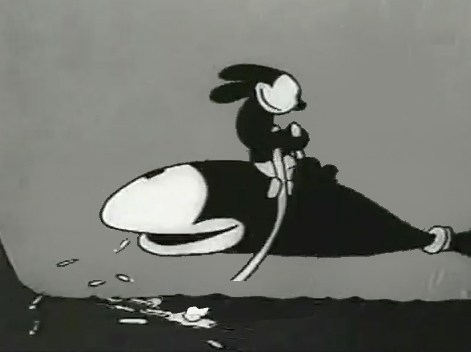

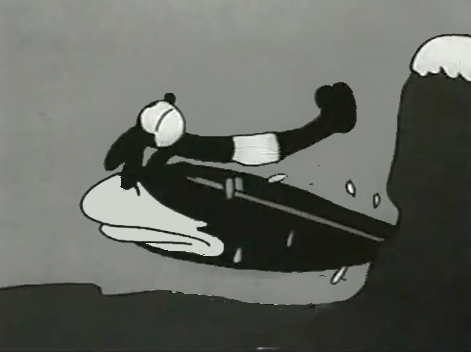

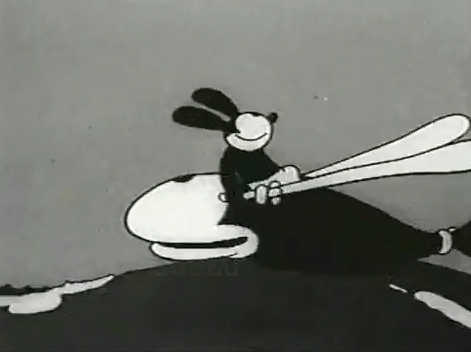

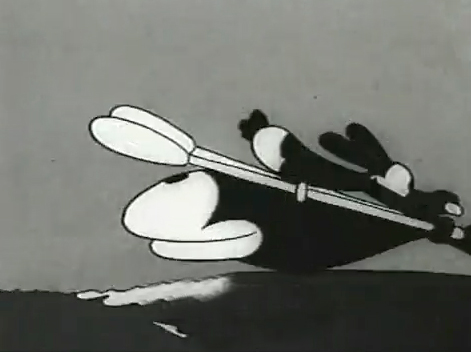

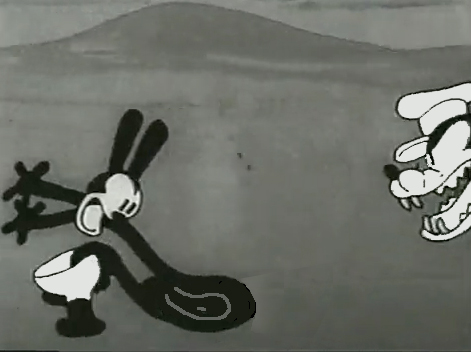

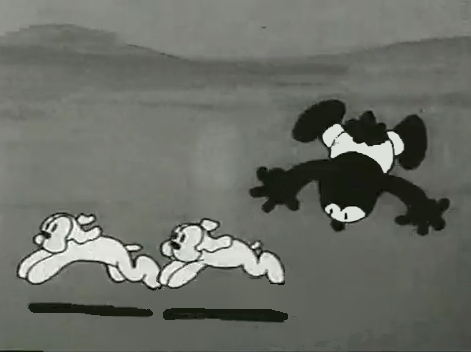

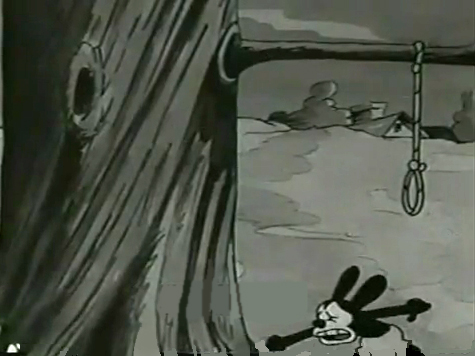

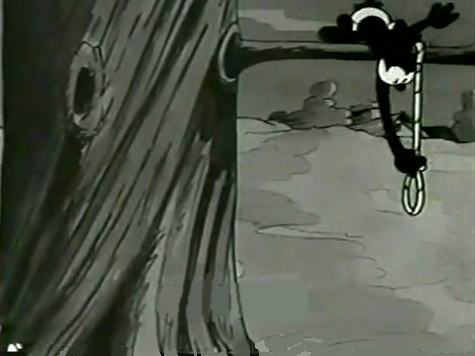

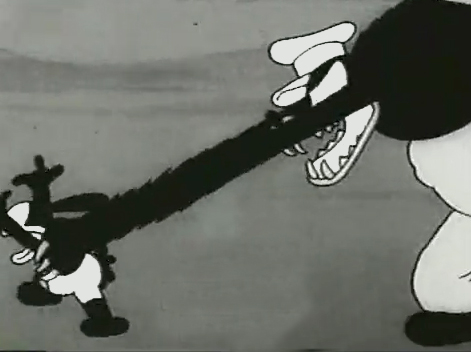

Nolan had developed a style known as the “rubber hose” style in that the limbs of a character were like flexible hoses and joints would be broken wherever the animator wanted. The style also featured very circular drawings. Stylistically, this fought the angularity of some other films that were being made and allowed Nolan to turn out many more drawings than usual. The roundness offered a faster line, and there was also quite a bit of distortion in Nolan’s drawings. Quite often the characters, Oswald, for example, didn’t even look like the character on the model sheet. In fact, you’d have to wonder if there was a model sheet, given the look of the animated character. Both Nolan and Iwerks were straight ahead animators, which meant they could easily go off model. Iwerks was better at holding things than Nolan, who seemed to enjoy being wild. Nolan would go back through his wild drawings and correct a couple of them, but would leave any other changes to lesser artists.

Nolan’s work was somewhat similar to the work of Jim Tyer, but I don’t think Tyer was drawing/animating that way to turn out faster work (though he was a very fast animator.) Nolan had to push the work out, and the rounded, distorted drawings enabled him to animate very quickly. As he went on, the artwork grew more and more wild, and it varied somewhat from the other animators’ work. Tyer tried to get his art to distort, as it does; Nolan just ended up there.

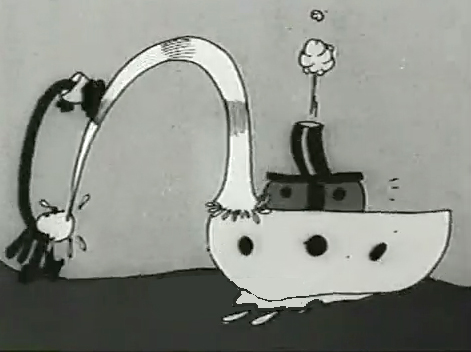

1

1  2

2I’d chosen a lot of stills from several of the

Universal/Lantz Oswald cartoons, animated by Nolan.

3

3  4

4

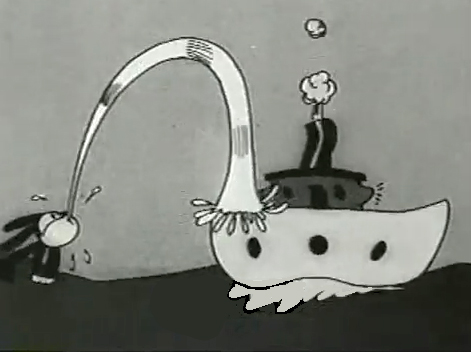

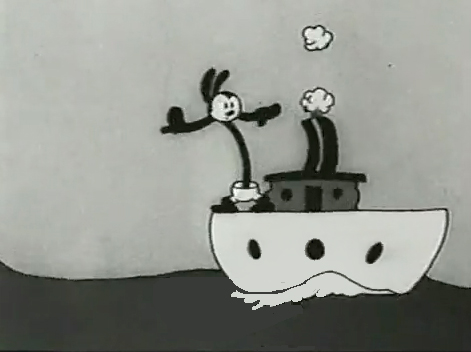

But so many of these from the short, “Permanent Wave,”

are good enough to illustrate my point.

13

13  14

14

His body moves out in front of his head

as it climbs up the water he’s spitting onto the boat.

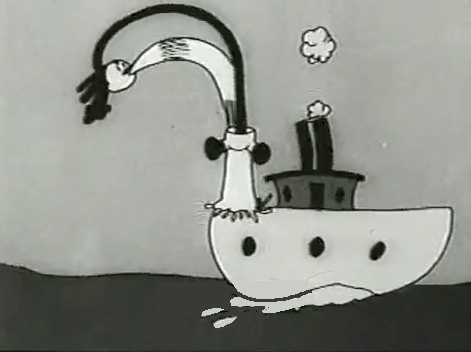

“The Hash Shop” was about as crazy as the animation and the gags went. Here’s one that ends the film.

By 1930, Bill Nolan seems to have settled down a bit. He still abstracts and distorts his animation, but he tries to fit in a bit more with other animators who aren’t drawing their animation quite so abstractly.

After Disney’s “The Three Little Pigs,” other studios tried to catch up with this new type of animation. Nolan and, to a lesser extent, Lantz, didn’t try very hard to change. They liked the way things were going. However, it didn’t take long for Lantz to move for a change in Oswald’s design. They went cuter and whiter on the rabbit.

Here are some frame grabs from “My Pal, Paul.” In it Oswald wants to play music with jazz conductor/musician, Paul Whiteman. As it happens, Whiteman’s car breaks down while he’s driving through the woods, and the two get a bit of a duo as Whiteman plays the steering wheel like a clarinet. (Maybe that’s abstract enough.)

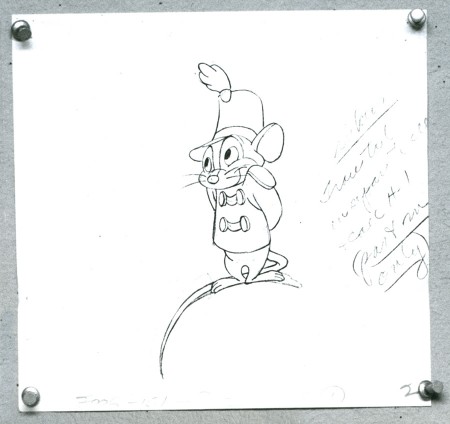

Action Analysis &Animation &Animation Artifacts &Disney &Tytla 13 Sep 2012 05:48 am

Tytla’s Terry-Disney Style

- Bill Tytla is probably the finest animator who has graced the history of the medium. He was a brilliant actor who dominates most of the classic early films of Disney work. Snow White, Pinocchio, Dumbo, and Fantasia are all appreciably greater films because of his work. In studying this master’s work frame by frame you can see a real elasticity to the character, one that is not apparent in the motion of those same characters. There’s true emotion in the acting of these characters, and it’s apparent that he uses that elasticity to get the performances he seeks.

There’s something else there: Tytla’s roots were in Terrytoons: I have no doubt you can take the guy out of Terrytoons, but it seems you can’t take the Terrytoons out of the guy.

Let’s look at some of the drawings from some of the scenes I posted here in the past.

Where better to start than with those gorgeous dwarfs from Snow White. Here’s a scene I posted where all seven are animated on the same level as they carry Grumpy to the wash basin. If he won’t clean himself, then the other six will do the job for him. Take a look at some of the distorted characters in this scene, then run the QT movie. Look for the distortion in the motion.

As for the drawing, like all other Tytla’s scenes it’s beautiful. But tell me you can’t find the Terrytoons hidden behind that beautiful Connie Rasinski-like line.

Flipping over to Stromboli, from Pinocchio, we find animation almost as broad as many Terrytoons, the difference is that Tytla’s drawing that roundness and those enormous gestures on purpose. He knows what he’s doing and is looking to capture the broad immigrant gestures of those Southern European countries. Stromboli goes in and out of distorted drawings, as I made clear in a past post.

75

75

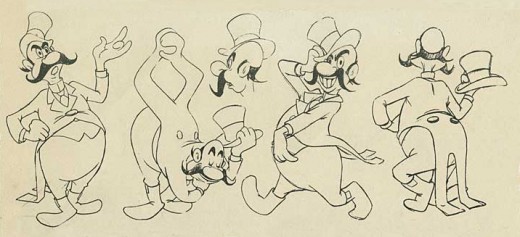

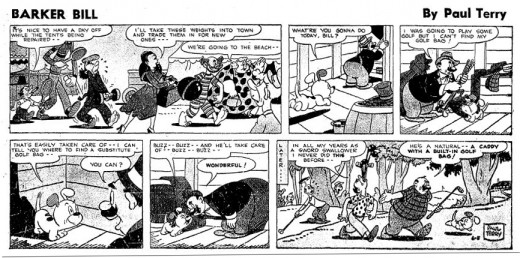

A strip by “Paul Terry”as starring his 1930s character, Barker Bill.

Borrowed from Mark Kausler’s blog It’s the Cat.

The Laughing Gauchito was a short that was, no doubt, going to be part of The Three Caballeros. Tytla, Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston had all animated for the short before Disney, himself, cancelled the production.

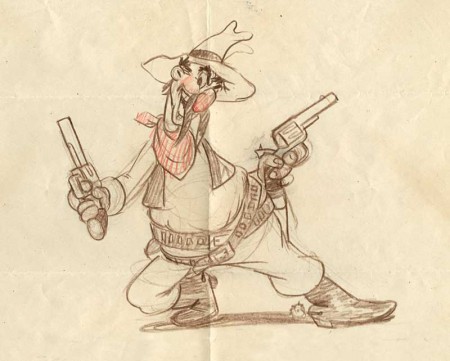

Here are three drawings from the film, and they are all beautiful extremes from the scene. (Tytla marked his extremes with an “A” to the right of the number, or at other times with an “X” in the upper right.) The beautiful roundness does not come at the expense of his drawings. Below the Laughing Gauchito we see a cartoon drawing by Carlo Vinci from a 1930′s Terrytoons short.

9

9

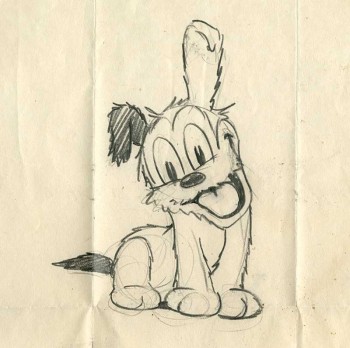

A Terrytoons drawing by Terry artist Carlo Vinci from a mid ’30s short.

borrowed from Animation Resources

Here’s a scene Bill Tytla did for a Harman-Ising cartoon. He was the supervising animator, and the lack of Disney becomes evident in the drawings. The animation is closer to a Terry short than what he did at Disney’s. The movement feels muddy in that actual cartoon. I’m sure it was his own animation trying to blend with the style of Harman’s work.

11

11

Another beautiful Carlo Vinci drawing from a 30′s Terry short.

borrowed from Animation Resources

And here’s a drawing out of a Little Lulu cartoon. I’s not a film directed by Tytla, and is not a good drawing. But Tytla’s influence on all the Lulu shorts at Paramount at the time can’t be denied. It certainly looks more Terrytoon than Paramount. This is not even a good Terry drawing – though its for a Paramount cartoon.

Back at Disney, Tytla animated Willie the Giant from the Mickey short, The Brave Little Tailor. This character, like Stromboli, owes a lot to Terrytoons. I felt this when I first saw the short as a child, and I still think it true. The same, I think, is also true of the same Giant character when he appears in Mickey and the Beanstalk, which Tytla obviously didn’t animate but would have handled if he’d stayed at the studio.

3

3

Another Carlo Vinci sketch.

borrowed from Animation Resources

This following, last drawing is a Tytla drawing I own. I know Tytla did it. He gave it to Grim Natwick who gave it to Tissa David who gave it to me. It’s a gem.

Animation &Disney &Peet &Tytla 10 Sep 2012 05:10 am

Dumbo Takes a Bath

- Bill Peet was a masterful and brilliant storyboard artist. Every panel he drew gave so much inspiration and information to the animators, directors and artists who’ll follow up on his work.

- Bill Peet was a masterful and brilliant storyboard artist. Every panel he drew gave so much inspiration and information to the animators, directors and artists who’ll follow up on his work.

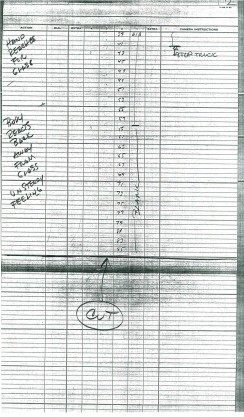

This is the sequence from Dumbo wherein baby Dumbo plays around the feet of his mother. Brilliantly animated by Bill Tytla, this sequence is one of the greatest ever animated. No rotoscoping, no MoCap. Just brilliant artists collaborating with perfect timing, perfect structure, perfect everything.

Tytla said he watched his young son at home to learn how to animate Dumbo. Bill Peet told Mike Barrier that he was a big fan of circuses, so he was delighted to be working on this piece. Both used their excitement and enthusiasm to bring something brilliant to the screen, and it stands as a masterpiece of the medium.

Of this sequence and Tytla’s animation, Mike Barrier says in Hollywood Cartoons: What might otherwise be mere cuteness acquires poignance because it is always shaded by a parent’s knowledge of pain and risk. If Dumbo “acted” more, he would almost certainly be a less successful character—”cuter,” probably, in the cookie-cutter manner of so many other animated characters, but far more superficial.

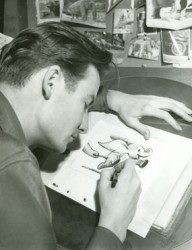

I had to take the one very long photstat, on loan from John Canemaker, and reconfigure it in photoshop so that you could enlarge these frames to see them well. I tried to keep the feel of these drawings pinned to that board in tact.

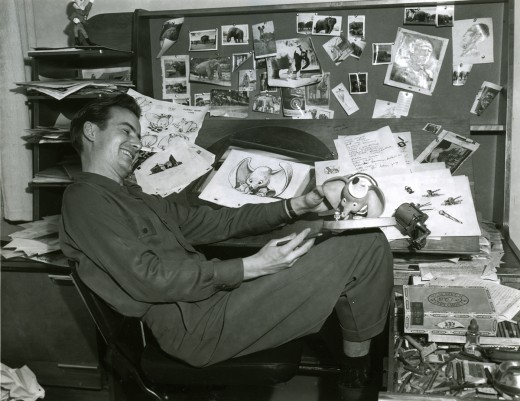

Bill Peet at his desk on Dumbo.

_______________________________________________

I think this sequence where Dumbo gets washed by his mother and plays around her legs is one of the greatest ever animated. There’s a sweet tenderness and an obviously close relationship between baby Dumbo and his mother which is built on the back of this sequence. It not only establishes both characters solidly, without words, but it sets up the mood of everything that will soon happen to the pair during the remaining 45 minutes of the film. Without that established bond, the audience wouldn’t feel so deeply for the pair during the “Baby Mine” song or care so much about Dumbo’s predicament.

I think this sequence where Dumbo gets washed by his mother and plays around her legs is one of the greatest ever animated. There’s a sweet tenderness and an obviously close relationship between baby Dumbo and his mother which is built on the back of this sequence. It not only establishes both characters solidly, without words, but it sets up the mood of everything that will soon happen to the pair during the remaining 45 minutes of the film. Without that established bond, the audience wouldn’t feel so deeply for the pair during the “Baby Mine” song or care so much about Dumbo’s predicament.

Tytla has said that he based the animation of the baby elephant on his young son who he could study at home. Peet has said that Tytla had difficulty drawing the elephants and asked for some help via his assistant. There’s no doubt that both were proud of the sequence and tried to take full credit for it. No doubt both deserve enormous credit for a wonderful sequence. Regardless of how it got to the screen, everyone involved deserves kudos.

Here are a lot of frame grabs of the sequence. I put them up just so that they can be compared to the extraordinary board posted yesterday. Both match each other closely. Whereas the board has all the meat, the timing of the animation gives it the delicacy that would have been lost in a lesser animator’s hands, or, for that matter, in a less-caring animator’s hands. The scene is an emotional one.

(Click any image to enlarge.)

Articles on Animation &Independent Animation &Tytla 07 Feb 2012 06:28 am

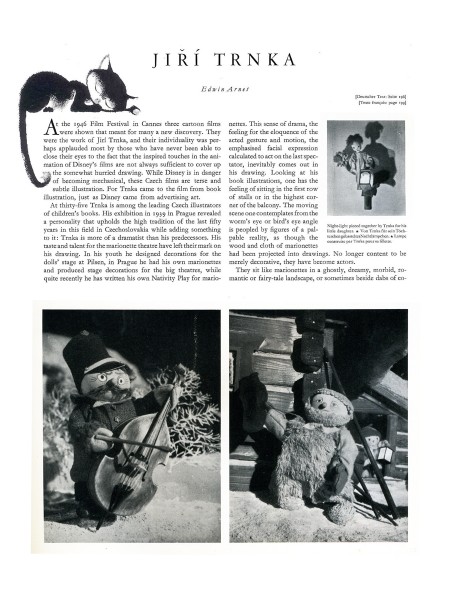

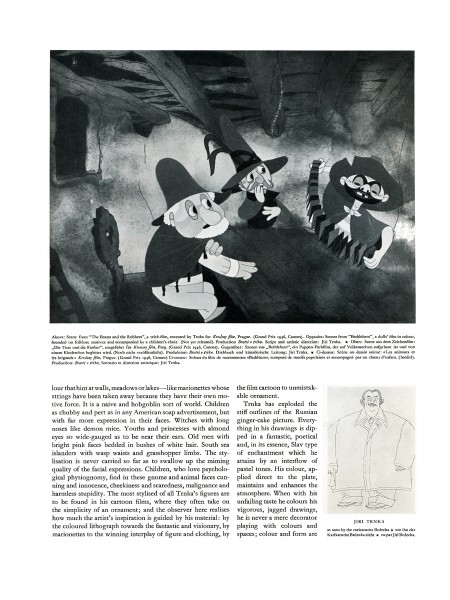

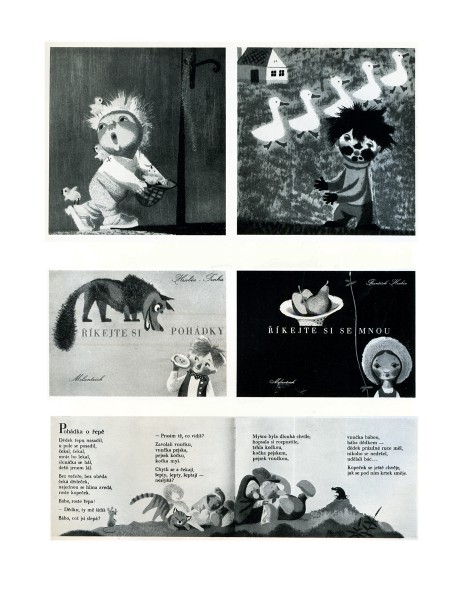

Trnka in Graphis, 1947

- Last week I linked to a post that Gene Deitch offered covering the Centennial of Jiřà Trnka‘s birth.

- Last week I linked to a post that Gene Deitch offered covering the Centennial of Jiřà Trnka‘s birth.

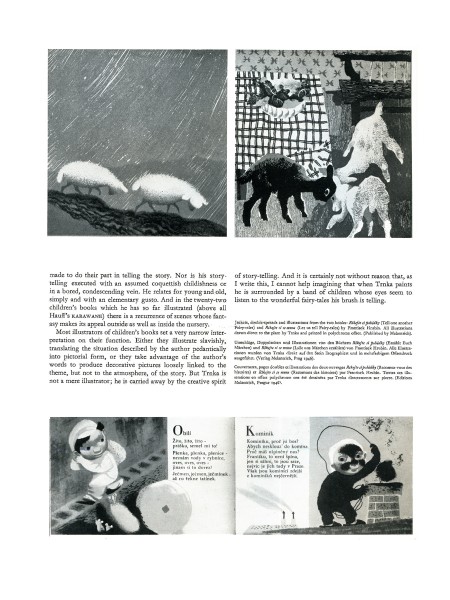

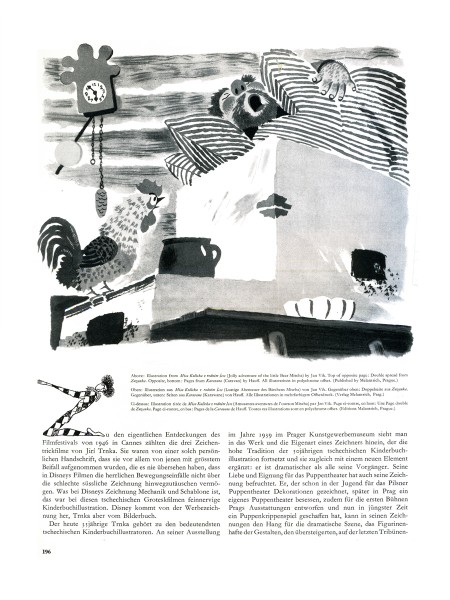

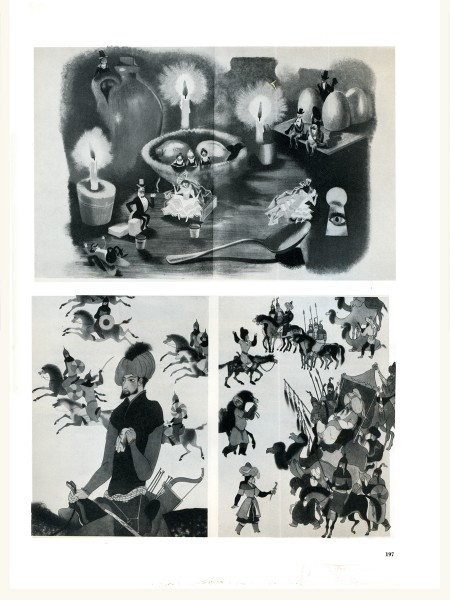

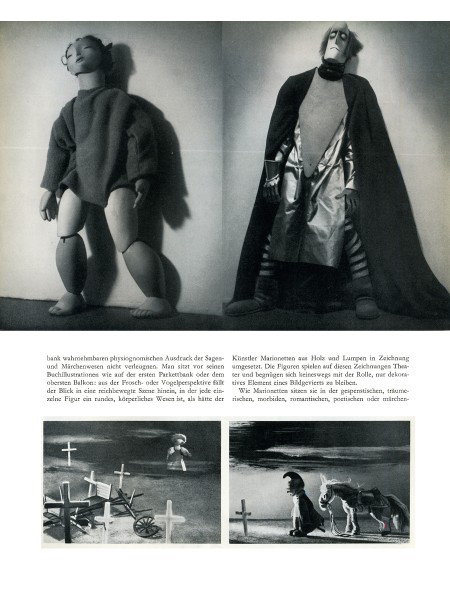

That got me to look back on some of the material I have featuring this exceptional artist. One of my favorite pieces appears in Graphis Magazine published in their 1947 edition. I’d posted this article in 2008 and am offering it again. I’d cut a few pages, which I’ve restored, and have also done a better scan of the pages.

It must be remembered that this article was published before any of the great Trnka films: The Hand, Archangel Gabriel and Mother Goose, or Midsummer’s Night Dream. Much of the piece is about his illustration work.

Regardless, it’s amazing how many beautiful images appear in his earlier films featured in this article.

(Note: Graphis is printed in three languages; all of the English is included.)

1

1 2

2 3

3 4

4 5

5 6

6 7

7 8

8

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Disney &Tytla 31 Aug 2011 06:55 am

Tytla’s Laughing Gauchito – a recap

- In the past few weeks, I’ve been recapping all of the Bill Tytla scenes I’d posted in the past. This is the last of those done for Disney, and I’m pleased to have it back up again. I’ve taken both parts of the original post and have incorporated them into this one.

- In March of this year, I posted, in three parts, Frank Thomas‘ animation on the short that never went to completion, The Laughing Gauchito. John Canemaker brought me Bill Tytla‘s scene from this very film, and I’m posting all of the drawings here. As I’ve said, Frank Thomas animated his beautiful and emotional scene and Tytla did this one for a film that Disney, himself, cancelled. He felt it was too much a one gag story.

This one came with the exposure sheets!

You should look into J.B. Kaufman’s excellent book, South of the Border; it gives a full accounting of this film.

Here’s the artwork.

The Background

1

1  2

2

These are the X Sheets for the scene.

Here’s a QT of the scene with all the drawings included.

These are the links to the Frank Thomas scene: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3

Many thanks to John Canemaker for the loan of the scene.

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Disney &repeated posts &Tytla 24 Aug 2011 07:09 am

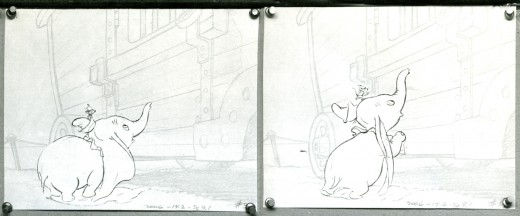

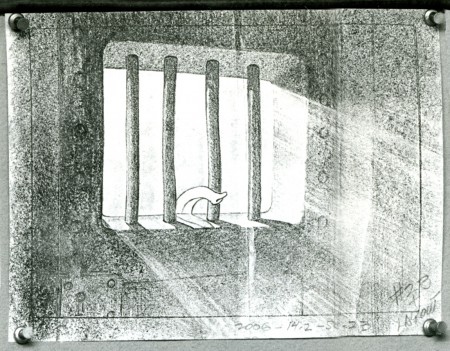

Baby Mine recap

To continue with all things Tytla, here’s a representation of the “Baby Mine” sequence from Dumbo. This is one of my very favorite sequences in one of my favorite animated films. The newish Blue Ray version of this film is excellent except for one thing. The commentary on this disc pales in comparison to the 60th Anniversary DVD. The original was done solely by John Canemaker and is enormously informative. I wish John would just turn that track into a book.

- Dumbo is certainly one of my favorite Disney features if not THE favorite. Naturally, the “Baby Mine” sequence is a highlight. The sequence is so tender and fine-tuned to appear straightforward and simple. This, of course, is the heart of excellence. It seems simple and doesn’t call attention to itself.

- Dumbo is certainly one of my favorite Disney features if not THE favorite. Naturally, the “Baby Mine” sequence is a highlight. The sequence is so tender and fine-tuned to appear straightforward and simple. This, of course, is the heart of excellence. It seems simple and doesn’t call attention to itself.

This is a storyboard composed of LO drawings from the opening of that sequence. They appear to be BG layouts with drawings of the characters cut out and pasted in place.

It’s not really a storyboard, and I’ve always wondered what purpose such boards served to the Disney machine back in the Golden Age.

Below is the board as it stands in the photograph.

_____________(Click any image to enlarge.)

Here is the same photographed board, split up so that I can post it in larger size. I’ve also interspersed frame grabs from the actual sequence for comparison.

Thanks to Steve MacQuignon for locating this video.

Info from Hans Perk at A Film LA:

Directed by Bill Roberts and John/Jack Elliotte, assistant director Earl Bench, layout Al Zinnen.

Animation by Bill Tytla (Dumbo & Mrs. Jumbo’s trunk), Fred Moore (Timothy) and assorted animals by Bob Youngquist, Harvey Toombs, Ed Aardal and John Sewell.

Hans Perk has posted the drafts for Dumbo, and this has led Mark Mayerson to post the brilliant Mosaics he’s created for the film.