Category ArchiveRowland B. Wilson

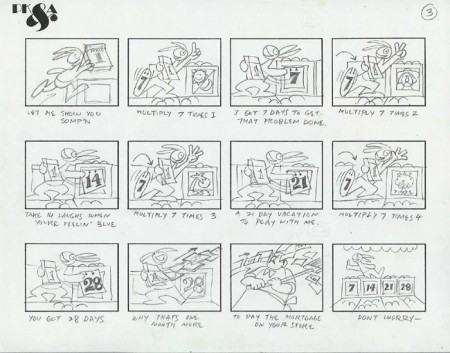

Animation Artifacts &Bill Peckmann &Rowland B. Wilson &Story & Storyboards 23 Sep 2009 07:37 am

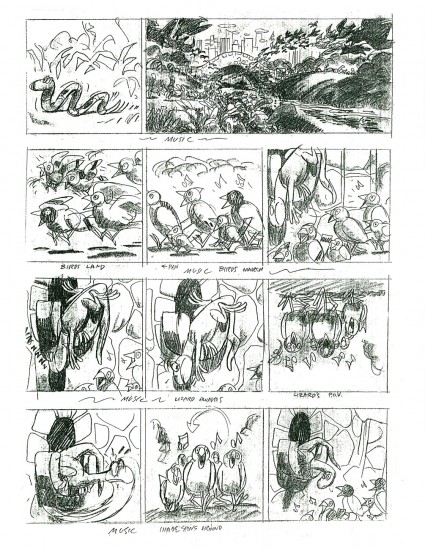

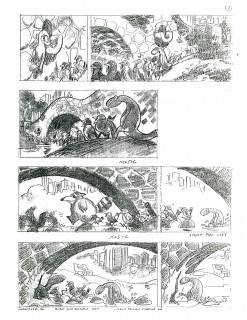

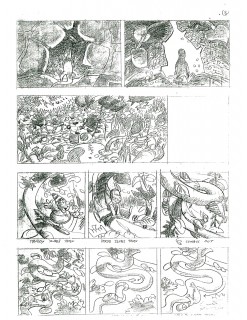

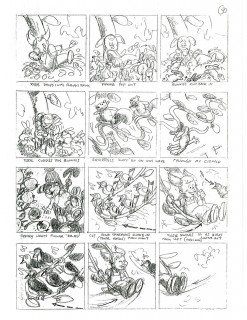

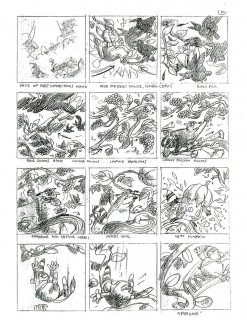

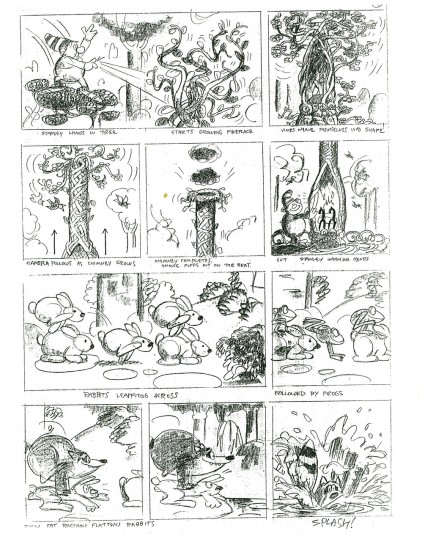

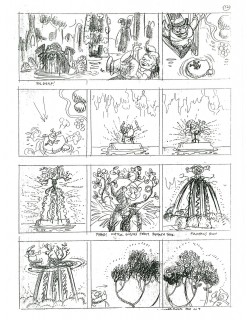

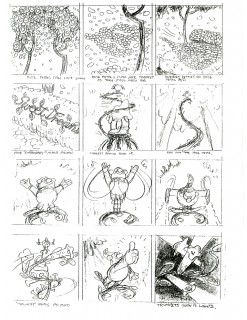

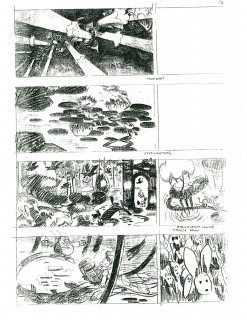

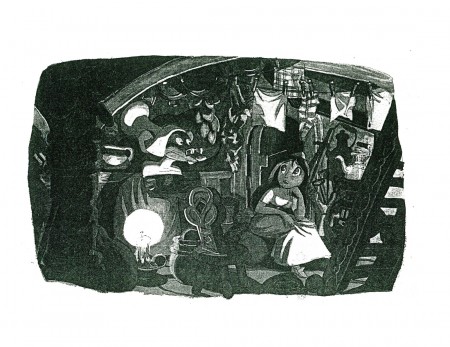

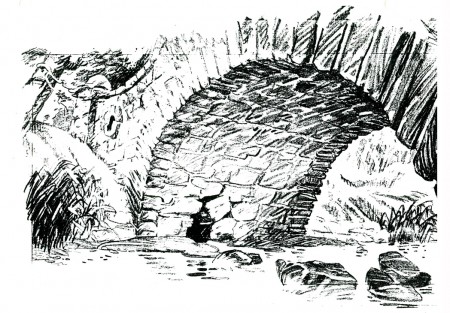

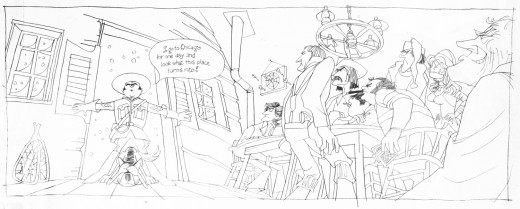

Troll Bd 1

- The animated feature is a funny business. So much work goes into them and so few give back the intended spark that the many creators think they’re investing in the labor. Such a film goes through many incarnations and struggles on its way to the public that it’s a wonder that it even makes it. And when it hits the theaters some jerk like me will dismiss it with a few bad words.

Don Bluth produced and directed as many as 11 feature films between 1982 and 2000. That’s a lot of work, and a lot of talented artists worked with him to get those flms to screens. Not all of them, obviously, were successful. I’ve read about The Pebble and the Penguin, but I don’t remember seeing it though I probably did; and if I don’t remember I may as well not have. Yet how much intensive labor by how many people went into making that film? How many years of work?

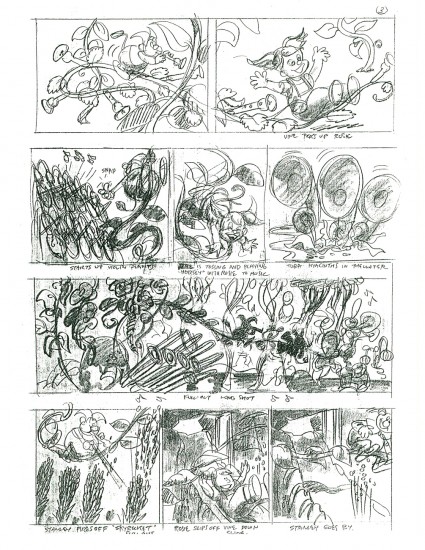

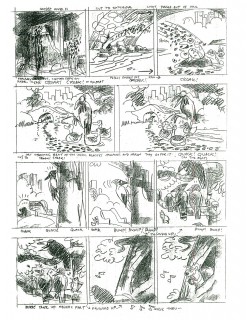

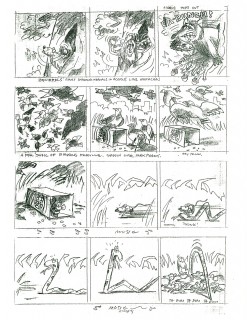

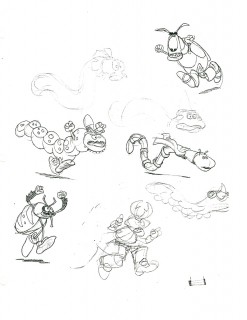

A Troll in Central Park is another one of those 11. I’ve seen parts of this film many times over. This is one of those films that I always seem to turn on at exactly the same moment and see the mid-section again and again. I admit that I haven’t seen it to the end. It has a very distinctive look, yet it wasn’t compelling enough for me to stay with it.

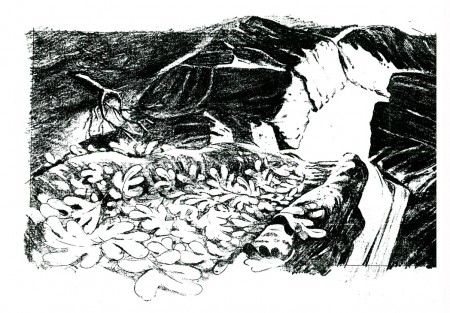

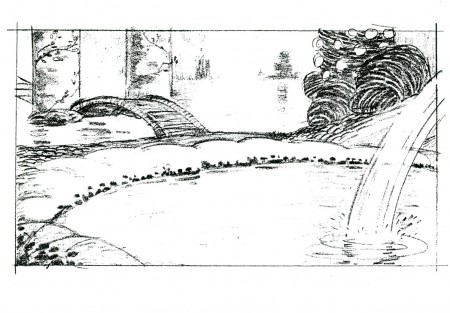

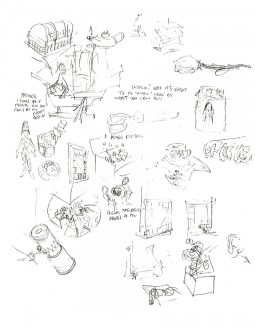

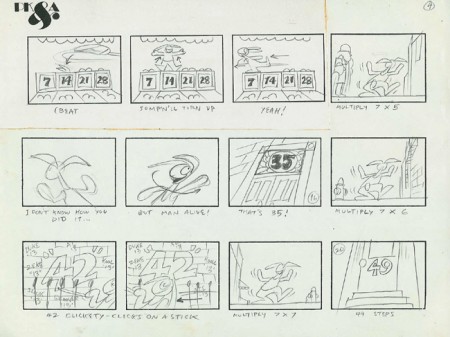

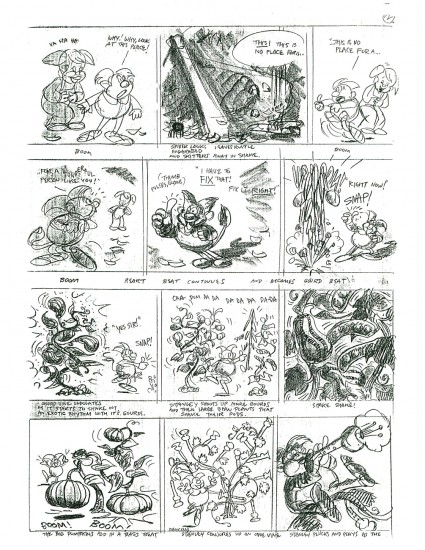

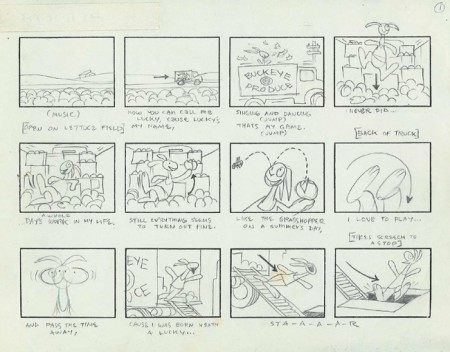

I have some of the storyboard sections done by Rowland Wilson, and I want to post them. There’s something to learn from every film fragment and this board offers much. Rowland was such a brilliant artist that it’s worth rummaging through any of his work, and he put a lot into all of it. This board is no exception.

Without further explanation or fanfare, here are 14 pages of board – actually I think they’re thumbnails – which were done by Rowland for A Troll in Central Park. These were given on loan to me by Bill Peckmann. His collection has been a real education for me.

1

1(Click any image to enlarge to a legible size.)

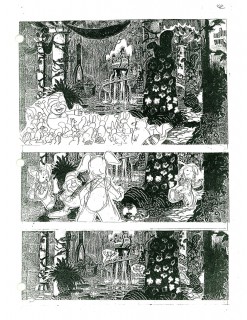

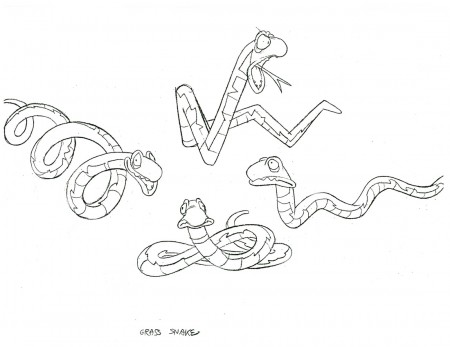

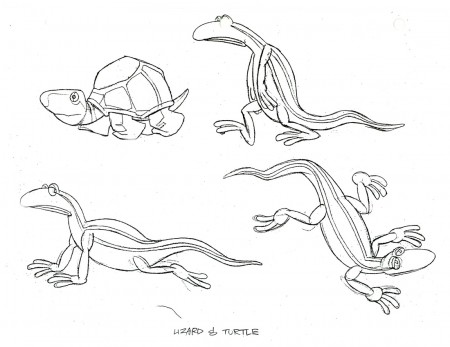

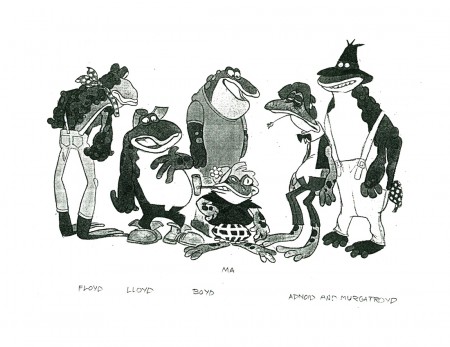

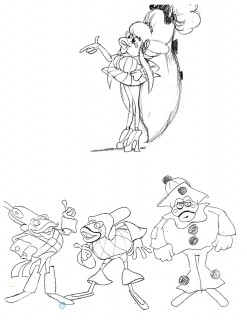

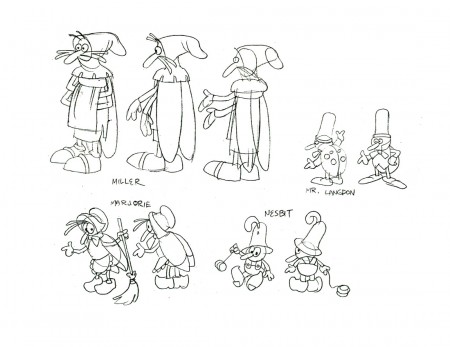

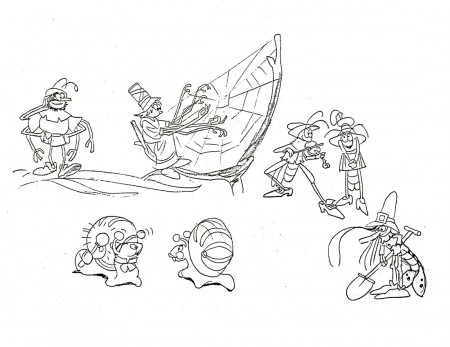

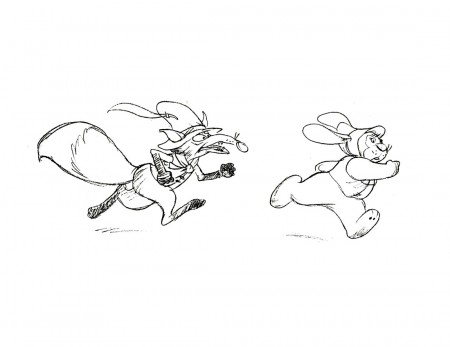

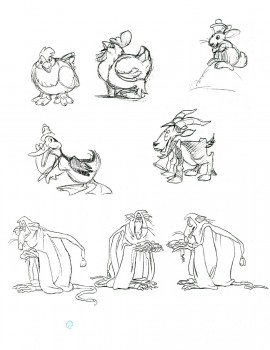

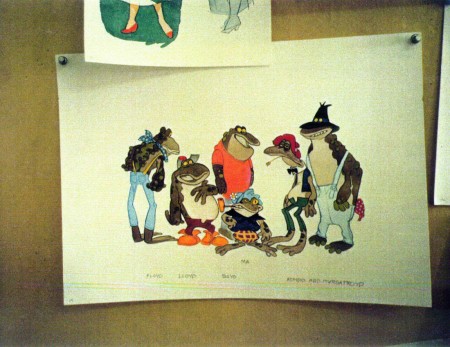

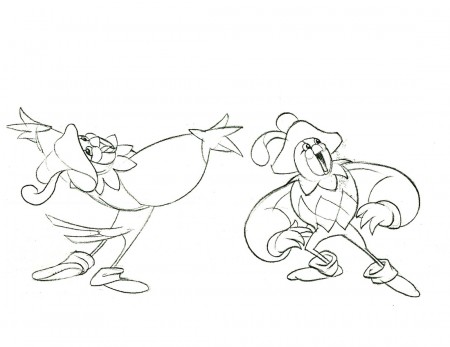

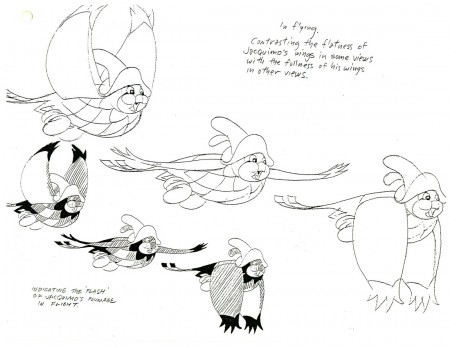

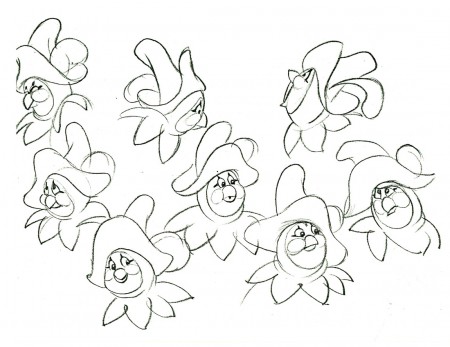

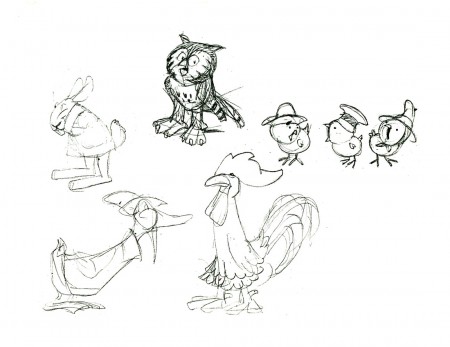

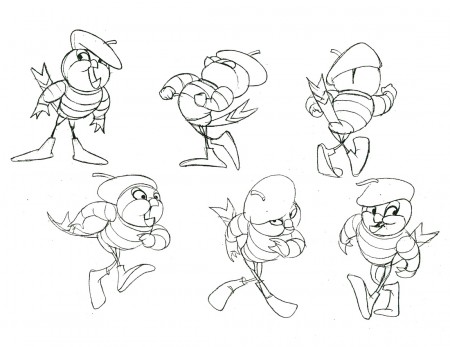

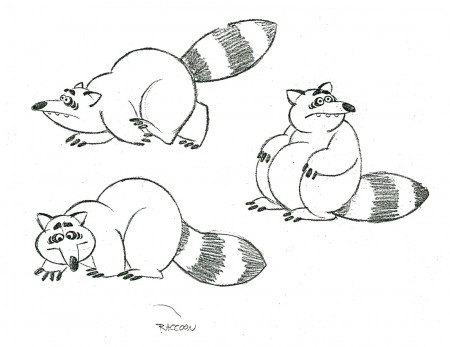

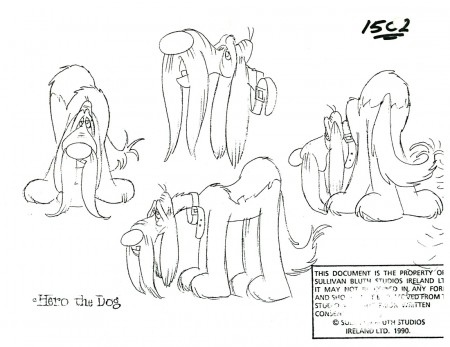

Here are a few character models for this sequence:

Can an animator have a better design for a racoon?

There’s enormous personality in this character.

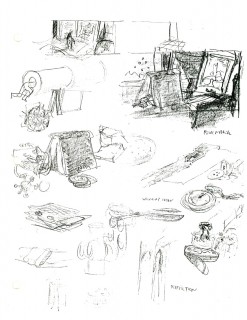

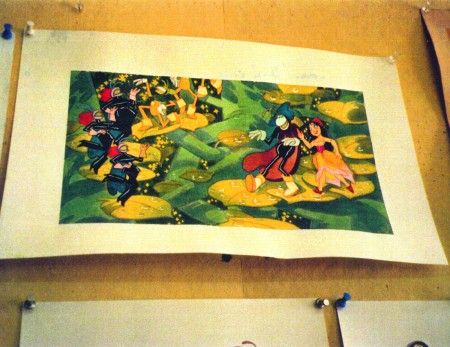

And here are some BG Layouts for this sequence:

1

1

I’ll put up more of these next week. Many thanks, again, to Bill Peckmann for the loan of this art.

Animation Artifacts &Models &Rowland B. Wilson 04 Sep 2009 07:37 am

more Rowland Wilson models

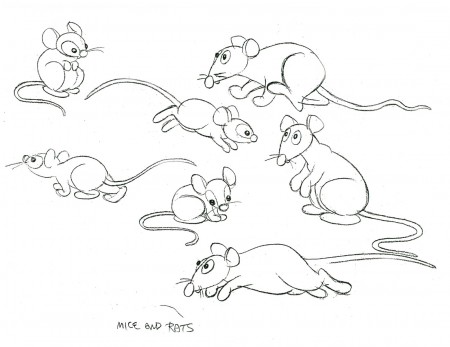

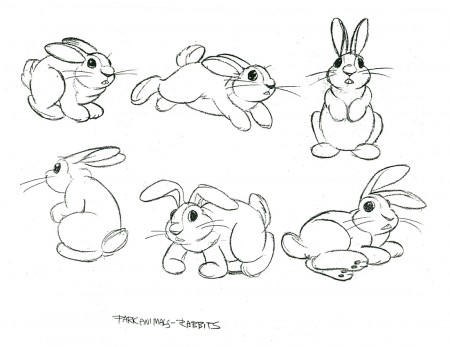

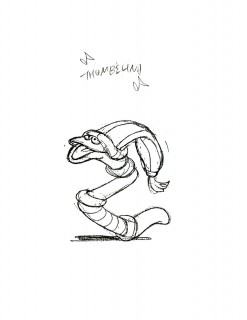

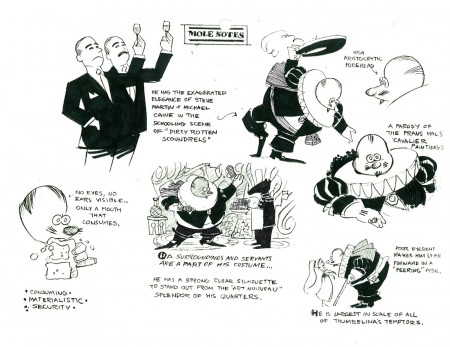

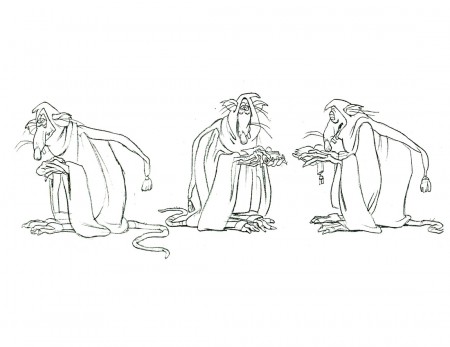

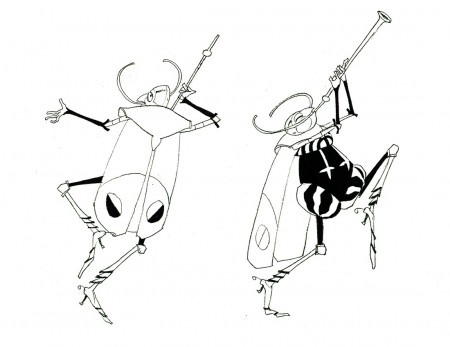

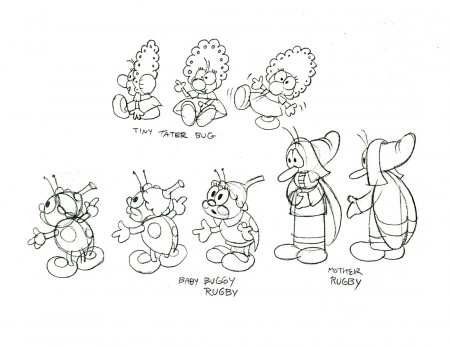

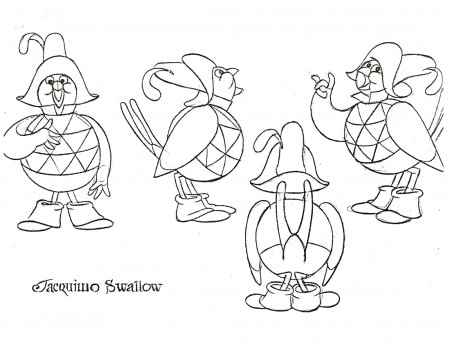

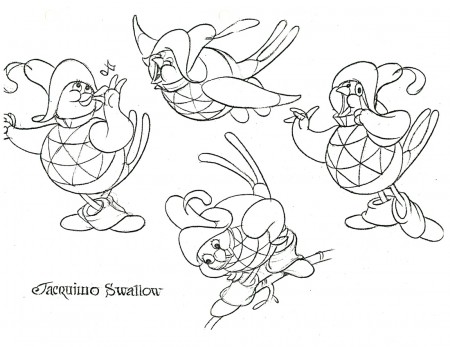

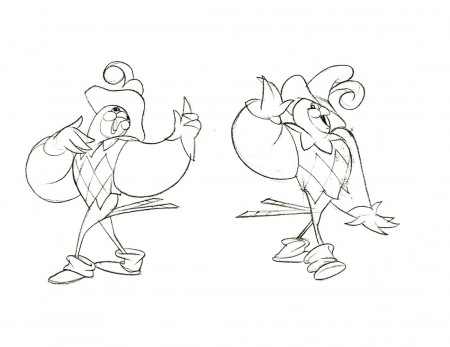

– Yesterday I began the display of models by Rowland B. Wilson done for SullivanBluth’s 1994 feature, Thumbelina. I have another large stack of them – all xeroxed copies, and I’ll try to get them all in today.

– Yesterday I began the display of models by Rowland B. Wilson done for SullivanBluth’s 1994 feature, Thumbelina. I have another large stack of them – all xeroxed copies, and I’ll try to get them all in today.

This film is far from the best of Don Bluth, but it goes to show how much solid work is done for any feature film. There’s also quite a bit to be learned from any feature. Many of these models didn’t end up in the film (take a look at Thumbelina herself in yesterday’s post) but the drive was a forward one.

Off to the modelshow:

1

1

(Click any image to enlarge.)

3

3

Another color one copied in B&W

30

30

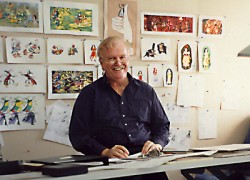

Finally, here are two color photos Rowland took of his presentation art.

Animation Artifacts &Bill Peckmann &Models &Rowland B. Wilson 03 Sep 2009 07:20 am

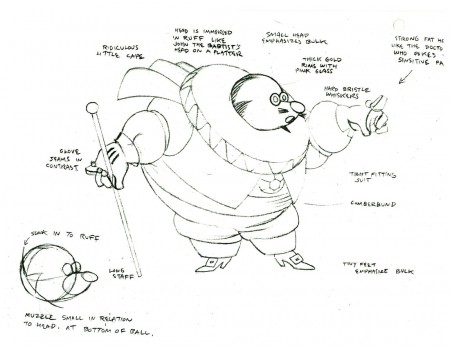

Rowland Wilson models

- In the past couple of weeks, we’ve seen a large group of Disney model sheets from some of the early shorts and features. I thought it’d be a good time to look at something more recent. Thanks to Bill Peckmann‘s extraordinary collection of design material, I have access to quite a few model sheets by Rowland B. Wilson.

- In the past couple of weeks, we’ve seen a large group of Disney model sheets from some of the early shorts and features. I thought it’d be a good time to look at something more recent. Thanks to Bill Peckmann‘s extraordinary collection of design material, I have access to quite a few model sheets by Rowland B. Wilson.

His models for Don Bluth‘s feature, Thumbelina, fill a binder. I’m gong to have to break it up into two posts.

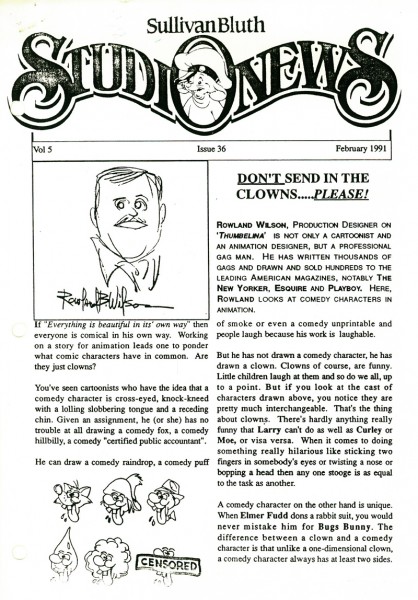

In this first one I’ll reproduce the article Rowland had written for the in-house organ “Studio News.” This follows with models for some of the lead character models.

These models were done in pencil and ink, sometimes in color. Unfortunately, all of these are 8½ x 11 xerox copies. Blacks wash out and washes blacken. Regardless, they all come across fine enough to get the idea.

Any feature takes a lot of work. You can understand that just in the large number of model sheets that grace the production. When you have a talented artist such as Rowland Wilson doing that modelling for you, your art is off to a good start.

1

1(Click any image to enlarge.)

1

1

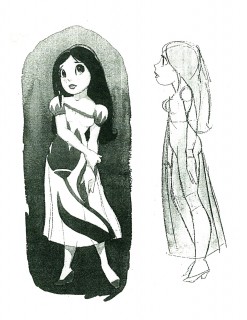

Here we have the model that Rowland drew for Thumbelina.

This is definitely not the rotoscoped princess that we saw in the film.

2

2  3

3

Here we have a lot of different costumes Thumbelina

will wear as she travels on her expeditions.

4

4  5

5

An original idea – a character who wears

more than one costume in a film!

Plenty of other models to follow tomorrow. Again, thanks to Bill Peckmann for the loan. It’s always great to showcase Rowland Wilson’s work.

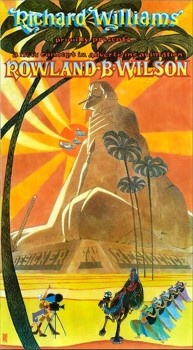

Photos &Richard Williams &Rowland B. Wilson 05 Feb 2009 08:51 am

Mystery Man

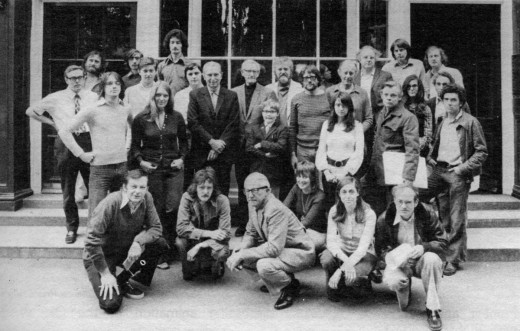

- Here’s a mystery that hasn’t been solved since 1975. It was posed to me by Tim Hodge. 1975 is the year Donald Heraldson‘s book, Creators of Life was published. In the book, there’s a team photo of Richard Williams’ staff sitting in front of the Soho Square studio.

(Click any image to enlarge.)

There in the center of the photo is a boy, arms crossed, standing in front of Grim Natwick, Ken Harris and (I think) Rowland Wilson, behind Art Babbitt kneeling. The caption beneath the photo reads: “Yes, the 10 year old boy is part of the staff – Williams considers him a prodigy.”

I know that Williams had taken Errol Le Cain under his tutelage in the 60′s and pushed him to animate the short, The Sailor and the Devil, on his own. However, Le Cain was born in 1941 and wasn’t 10 in 1975.

Perhaps Williams was high on this kid at the time of the photo, but soon grew tired of him and moved on after a couple of months. Or maybe the boy, who’d be in his 40′s now, became one of our top animators.

Or maybe the book, which is filled to the brim with errors, actually misunderstood the role of the child in the studio. (He may just have been someone’s child.)

Well, the question is: who was that “10 year old boy”?

If you have any idea, please leave a comment.

Actually, if you can identify others in the photo, please don’t hesitate to share the info.

Bill Peckmann &Daily post &Rowland B. Wilson 20 Dec 2008 09:14 am

Rowland Response

- My piece, posted Dec. 6th, on Rowland Wilson brought a couple of responses via email.

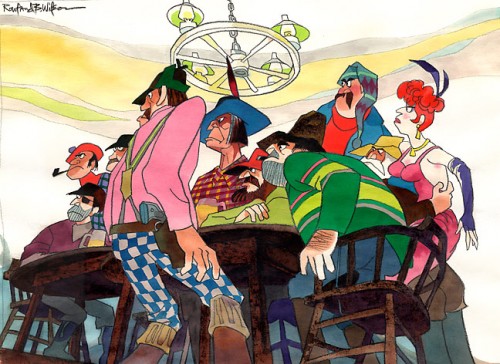

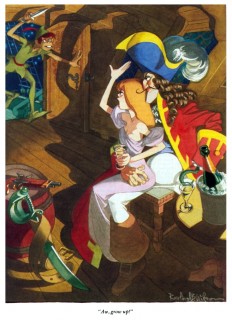

Thanks to George Griffin, I was able to post a caricature of the staff of the commercial studio, Focus, done by Bill Peckman, in the style of Rowland Wilson. To remind you, let me post that drawing again here.

(Click any image to enlarge.)

This prompted Rowland’s wife, Suzanne Wilson to send me this message in a note:

- Enjoyed the Focus on Focus soooooo much!

Thought I would pass along the two Rowland B. Wilson originals that Bill Peckman’s caricature was based on. (Love the “No Credit” sign in the Malamute Saloon!)

It’s great seeing how Bill adapted Rowland’s work, and I thank Suzanne enormously for sharing the artwork.

Then I heard from Borge Ring, who wrote a lengthy comment that was just great to read:

- I knew Rowland Wilson well during the 1970s. We both worked at Dick Will1am’s delightful London studio, often at the same commercials. Rowland was very good company, and his interest in the craft had as many antennas in the air as your blog which is my number one art gallery.

Rowland had fallen in love with animation and joined Dick’s studio to follow Art Babbitt’s lectures. He was intensely busy because next to his work for the studio, he drew well paid advertising cartoons – complicated ones – for a NY ad agency. He always came in early and he worked Sundays but rarely at night. “He said: “That which takes you three hours to get right in the night, you can do in twenty minutes in the morning”

Blake Edwards ordered a 5-minute title for his coming Pink Panther film. It got built “straight ahead” as it were, like at a story conference by a threesome: Dick, Rowland and Ken Harris. So Rowland based upstairs under the roof did a lot of stairs-running in the little old building carrying papers with ever changing concepts. Meanwhile Ken animated the Panther doing a tap dance with straw hat and cane, He confided that: ” If the body movements are right, it does not matter what the feet are doing, as long as they do a lot.” And Dick invented – among other things -how to do Black and White neonsigns for the occasion.

His business partner appreciated the creative euphoria but looked worried because: “Dick is going to spend all the money polishing the animation.”

Rowland designed the famous VODKA commercial, you mentioned, on large celluloids using the broad side of his crayons. He also animated one of the scenes with a locomotive stoker in silhouette throwing a shovelfull of coals into the furnace. His draftsmanship made the short scene look like a piece of live action.

Rowland was helpful to everyone. I once saw him showing a young artist the difference between drawing Disney style figures and “New Yorker style” cartoons. “On the one you whittle away until you get it right. The other one must be there at first stroke, If it isn’t right you don’t whittle. You do a new one”.

“Borg,” he announced, sliding the door to my cubicle. ” The client wants another broooad in thaare” meaning that there would now be four housewives instead of three in the scene. Rowland was a Texan and it was fun to hear this gentle person sound like Hopalong Cassidy.

Rowland cherished the company of Grim Natwick. “He certainly does”, said Dick. “Because he and Grim can talk for hours about …ART. Grim is good, but he is full of bullshit.”

Dick pretended to be allergic to “intellectualism”. He and Art Babbitt shared an office. “Don’t worry … Art is on a culture kick,” he said with a grin. “He has been talking to me for months about a man he calls Moliere; and he hasn’t found out that I don’t know who that is”.

Putting Moliere’s comedies on film was an early dream with UPA when they started.

I think that Rowland’s stint at Dick’s studio was a high point in his career, and his girlfriend Skeesik informed us that, “Life is an acquired taste.”

ps

Rowland and I were having Timsum in Chinatown, and I said: ‘All you guys who draw cartoons in Playboy and the New Yorker. I suspect that your innnermost desire is to draw and paint with light and shadow like they did during the Italian Renaissance. You cannot sell Madonnas and Jesuses, so you opt for illustrating intelligent jokes in elite publications”

He stopped eating and gazed at me.

“Can YOU see THAT?

“Well. a blind chicken finds a grain once in awhile, my dear Watson.” I said trying to hide my own surprise at having scored.

yukyuk

Bill Peckmann &Daily post &Rowland B. Wilson 15 Dec 2008 08:50 am

Focus on Focus

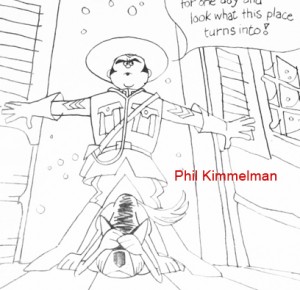

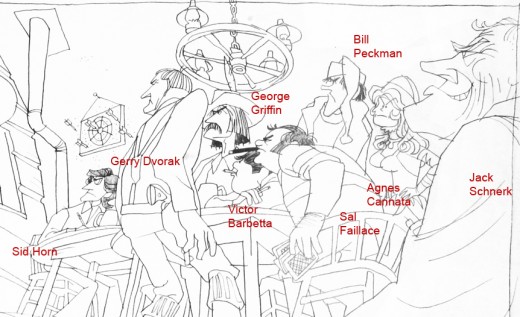

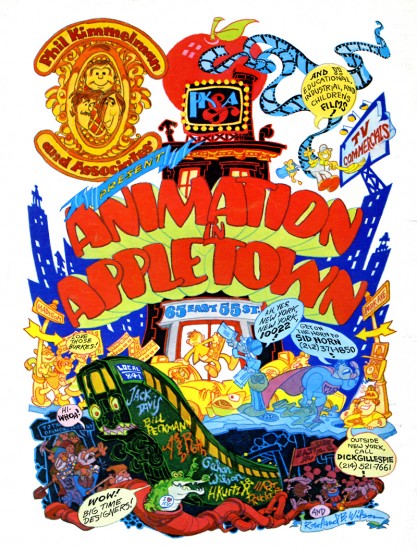

- Here’s a surprise gift from George Griffin. It’s a studio caricature of the commercial studio Focus (this predates even Phil Kimmelman’s own company, PK&A). I’ll let George’s own words inform us about it:

- I came across this copy of a drawing by Bill Peckman you might want to share on your blog. It shows Bill’s adaptation of Rowland Wilson’s design into caricatures of the staff at Focus Design. Wilson had just designed a spot we had all worked on. Phil Kimmelman is the Mountie/authority figure and to the right, Sid Horn, Jerry Dvorak, yours truly, Victor Barbetta, Sal Faillace, Bill, Agnes Cannata and Jack Schnerk. The likenesses are very accurate but the character of each person was inverted: Phil was very sweet and easy-going, Bill and everyone else was very happy, not at all like these scowling toughs.

.

.

.

I’ve split the drawing up and used George’s key to mark up and identify the people within the caricature to make it a bit easier to read.

Michael Barrier has just reviewed both Madagascar 2 and Bolt. His review, as expected, is from a singular perspective though I think he touches on thoughts we’ve probably all had. I look forward, always, to his honest comments.

And speaking of Michael Barrier, Kellie Strøm pointed to a Phil Kimmelman ad on the back page of Funnyworld 20. This was a comment on my Ads for Ad Companies post. Though Kellie links to the ad, I thought it worth post here on its own. It’s a Rowland Wilson illustration.

_______________________

_______________________ A blog I’ve just stumbled upon is Ian Lumsden‘s Animation Blog. It’s a British blog with some astute commentary; most of it involving British animated films. The posts on this blog have introduced me to several animators whose work I was unfamiliar with, and whose films I find worth watching out for. The most recent filmmaker under discussion is Ivan Maximov.

-The NYTimes, yesterday, featured an article about Ari Folman and his feature film, Waltz With Bashir. The film’s about to be released this next week, and this is the start of the relatively small PR run. Here’s hoping this adult film will be noticed by the Academy voters. This is one of two animated films eligible for Oscar nomination in the category of Best Animated Feature that is considered an Israeli film. The other is $9.99 now playin in LA and soon to be released in NY.

-The NYTimes, yesterday, featured an article about Ari Folman and his feature film, Waltz With Bashir. The film’s about to be released this next week, and this is the start of the relatively small PR run. Here’s hoping this adult film will be noticed by the Academy voters. This is one of two animated films eligible for Oscar nomination in the category of Best Animated Feature that is considered an Israeli film. The other is $9.99 now playin in LA and soon to be released in NY.

Articles on Animation &Rowland B. Wilson 02 Dec 2008 09:10 am

Rowland Wilson

- Rowland Wilson was one of those artists/cartoonists who was loved by everyone.

Long before I saw his connection to animation, I knew his amazing cartoons in Playboy. They were full page color images that were gorgeous to look at, and it was irrelevant whether they were funny or not. They were beautiful.

I met him only once on the School House Rock pieces he designed for Phil Kimmelman‘s PK&A back in 1973. I was an Asst. Animator there working on the spots that were animated by Jack Schnerk, Sal Faillace or Dante Barbetta. My meeting was little more than a hello.

I met him only once on the School House Rock pieces he designed for Phil Kimmelman‘s PK&A back in 1973. I was an Asst. Animator there working on the spots that were animated by Jack Schnerk, Sal Faillace or Dante Barbetta. My meeting was little more than a hello.

I knew Rowland’s daughter, Amanda, who worked on Raggedy Ann, opaquing. We kept in touch for a short while after the film’s

_..__ Phil Kimmelman and Rowland Wilson__________completion. She continued in the NY

__________________________.__________________animation community for a while, until work dried up. Unfortunately, I’ve lost track of her.

Of course, it would have been Richard Williams that put him to work seriously in animation. Together they created the stunning ads for Count Pushkin Vodka. This was the

high water mark of his and Williams’

ad films. I think this ad campaign was one of the high water marks for advertising, in general. The Wilson and Williams’ work is extraordinary.

He did design work on The Cobbler and the Thief after which he worked with Bluth for a short while in Ireland on Thumbelina and A Troll in Central Park. For Disney he did “Visual Development” and “Character Design” on The Little Mermaid, Treasure Planet, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Hercules, Atlantis and Tarzan.

Creative Talent Network has a nice page up for him here. They also offer an extensive resume here.

Creative Talent Network has a nice page up for him here. They also offer an extensive resume here.

Mark Kennedy offers a number of Wilson’s handouts on color, light and shadow and composition.

AWN had a fine memorial piece to Wilson written by John Culhane. here

I’d like to post here some of Myrna Oliver‘s obit from the LA Times 7/11/05:

- Born Aug. 3, 1930, in Dallas, Rowland Bragg Wilson grew up drawing Disney characters at the kitchen table. He received a bachelor’s of fine arts from the University of Texas at Austin and then moved to New York City for graduate work at Columbia University.

To support himself, he began creating gag cartoons for the Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s, Look and True magazines. He was drafted into the Army, serving from 1954 to 1956, where he used his artistic talents to draw classified charts.

In 1957, Wilson joined the Young & Rubicam Inc. _____a poster done for Dick Williams

advertising agency where he spent seven years as

an art director, doing conceptual drawings for print ads.

At the same time he stepped up his freelancing of cartoons to magazines and became a regular with Esquire in 1958. In the late ’50s and early ’60s he also had cartoons published in the New Yorker.

He established himself as a freelance advertising artist in 1964 but never gave up cartooning, which he described as “picture writing.†Forced by his lucrative advertising contracts to limit cartoon work to a single magazine, he focused on Playboy after Esquire abandoned its full-page cartoons.

He established himself as a freelance advertising artist in 1964 but never gave up cartooning, which he described as “picture writing.†Forced by his lucrative advertising contracts to limit cartoon work to a single magazine, he focused on Playboy after Esquire abandoned its full-page cartoons.

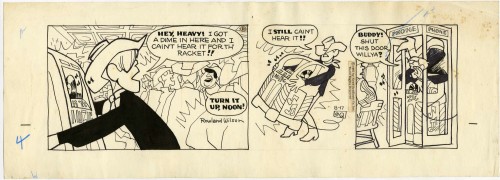

In 1967, he also drew “Noon,†a short-lived comic strip for the New York News-Chicago Tribune Syndicate (Tribune Corp. now owns the Los Angeles Times).

As Wilson once described the strip, “The name of the main character was Noon Ringle, an unemployed cowboy in a dying small Texas town in sort of modern times.â€

Wilson illustrated two children’s books in the early ’70s, “Tubby and the Lantern†and “Tubby and the Poo-Bah.â€

It was advertising that moved him into ________a Rowland Wilson cartoon for Playboy

animation, and from 1973 to 1975 he worked in

London as a designer for the primarily commercial animation studio of Richard Williams. On his return to New York, he joined Phil Kimmelman and Associates, which concentrated mainly on advertising work.

In his cartoons, advertisements, designs for animated characters and illustrations, Wilson was known for three-dimensional drawings filled with historical detail.

“Ideas are easy to come by,†he often said, according to his daughter. “It is the drawing that takes a long time.â€

A sample of the strip “Noon”

As an animator, Wilson won a daytime Emmy Award in 1980 for his work on ABC’s “HELP! Dr. Henry’s Emergency Lessons for People†and worked on educational animation, including the television series “Schoolhouse Rock.â€

In 1975, Wilson won awards at the Venice and Irish Animation festivals, and his animated commercial film “The Trans-Siberian Express†won first prize at the third International Animation Festival in New York. He also won a Clio.

He worked for Walt Disney Feature Animation as a visual developer and served as a layout designer for “The Little Mermaid†in 1989. He also contributed to “The Hunchback of Notre Dame†and “Tarzan†among others.

But Wilson’s greatest legacy may be on the printed page. His cartoons, widely published in magazines, were reprised in several anthologies, beginning with “Don’t Fire Until You See the Whites of Their Eyes,†a collection of his Esquire work published in 1963. He earned Playboy’s Cartoonist of the Year award in 1982 and his work was included in the 2004 anthology “Playboy – 50 Years: The Cartoons.â€

For all Wilson’s love of animation, “It was sketches for a new Playboy cartoon that were on his drawing board when he died,†said his daughter Megan Wilson.

Wilson also worked extensively in advertising and was particularly lauded for his 40 or so humorous works for New England Mutual Life Insurance Co. Each cartoon-type ad depicted a person in dire straits – such as an executive with his back to a high-rise office window as a wrecking ball swings toward him, proclaiming, “My life insurance company? New England Life, of course. Why?â€

Wilson’s first marriage to Elaine Libman ended in divorce. He is survived by his second wife, artist Suzanne Lemieux Wilson; four daughters, who are all commercial artists, Amanda Wilson of Piermont, N.Y., Reed Wilson of London, Kendra Wilson of Leicestershire, England, and Megan of New York City; and three grandchildren.

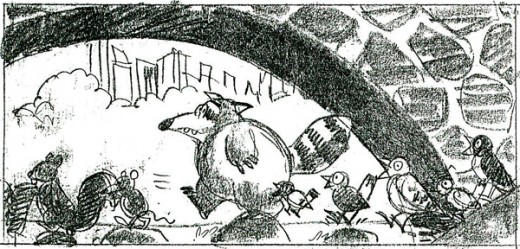

The storyboard by Rowland Wilson for “Lucky 7″ Schoolhouse Rock.

Art available on Amazon from Creative Talent Network.

.

Articles on Animation &Bill Peckmann &Rowland B. Wilson 29 Nov 2008 09:46 am

Producers of 1976

- Last Tuesday I featured the Young Independent animators of 1977. Today let me showcase a couple of commercial producers from the same period. This article came from the famous Raggedy Ann issue of Millimeter/1976, edited by John Canemaker. It was part of their regular column:

PHIL KIMMELMAN

Phil Kimmelman is a New Yorker who stayed. “My love was always animation,” says the cherubic President and Director of Animation at Phil Kimmelman & Associates. At 17, he gave up a three-year scholarship to go to work for Paramount Famous. It was the 50′s; Hollywood was doing fine; budgets were big in the New York animation departments. “I’m delighted to have been a part of that. It really did a lot for me.”

Phil Kimmelman is a New Yorker who stayed. “My love was always animation,” says the cherubic President and Director of Animation at Phil Kimmelman & Associates. At 17, he gave up a three-year scholarship to go to work for Paramount Famous. It was the 50′s; Hollywood was doing fine; budgets were big in the New York animation departments. “I’m delighted to have been a part of that. It really did a lot for me.”

After gaining some experience at Kim-Gifford and Chad Studios in New Jersey, Phil served a stint in the army as an illustrator. In 1961, he joined Elektra as an animator and animation director. “Elektra was into experimenting. We were really into exploring new areas. I think that’s where it all began for me.”

After five years, Phil left Elektra for Focus. Four years later (1971), he opened his own shop. “Fortunately, I wasn’t enough of a businessman at the time to realize how bad things were. We staffed up rather heavily at a time when everybody was resorting to freelance … we got into some problems, but now we’re busier than ever.”

“I consider myself part of a team, the other part being Bill Peckman, one of my associates. We’ve been together through Elektra and Focus. I think Bill’s one of the best talents in this business . . . and I’m glad he’s with me.”

Phil’s other associates are Bill Hegman, designer, and Sid Horn, production manager. Morty Gerstein, a former competitor, is now affiliated as a designer/director. Working madly in the next room is Roland Wilson, a Playboy cartoonist beloved by ad folks for his New England Life campaign.

These gentlemen are just the tip of the iceberg. PK & A is crawling with creative types, and the company has recently leased additional space. “One of the things that has made us successful is the versatility of our reel. We’re great admirers of a lot of cartoonists and designers from outside. If a job comes through that we feel requires a certain look—like a Gahan Wilson or a Jack Davis—we’ll put our own egos aside and go after them. I’ll give you one example: Harvey Kurtzman. Harvey is the creator of Little Annie Fanny for Playboy. He’s best known, I guess, for starting Mad Magazine (he’s no longer with them). We’ve always been fans of Harvey Kurtzman—I think the man’s an absolute genius. Bill Peckman and I chased after him, and he was very apprehensive about working in animation. He said he had a bad experience at one time. But we got him to look at our reel, and at the end of it, he applauded and said he’d be willing to chance it again. So we had Harvey design and write some scripts for Sesame Street, which we’ve sold and produced, and we’ve won a lot of awards with them. They’re beautiful spots—and they’re one example of the ‘Kimmelman look.’ ”

Yes, but how does he work with agency art directors and writers? “When an agency board comes in, I like the option of taking the board and recreating it to our way of thinking. Generally, that’s why they come to us—for our input. I think a lot of art directors and writers are not really geared, you know, to think animation. When he or she gets involved in animation, there’s a long time period where there’s very little to do. You know, it’s difficult for the people in agencies who are making the schedules to understand the time element. Where we used to have a good eight weeks to do an average 30-second commercial, we’re constantly being asked to do it in four or five weeks. It’s what I see happening more and more today that kind of upsets me. We’re working nights—around the clock—too often. That’s what it’s become. I guess we love it enough to keep doing it. I do have a line I won’t go over. If I really feel it can’t be done, we won’t do it. I’ve been in that situation many times.”

What about Ralph Bakshi and his controversial coonskins? “Fantastic. Whether you or I like his films, there’s no question that they’re breakthroughs. He’s gotten animation into the adult mind. For that reason alone, I’m delighted it’s happening.

“I think it’s sad. So much more should be happening in this industry. I think animation still hasn’t been scratched. It’s an extension beyond what live can do. There’s no limit. There are people who think it’s a dying art. I don’t think it will ever die. I’m very optimistic about that. I think, if anything, it can only go upward.”

JERRY LIEBERMAN

Jerry Lieberman says he originally “wanted to be a doctor,” and he endured two years of pre-med before allowing all the “fantasy, other-world head aspects involved in growing up in corny, carny, show-biz pizzaz-zy Atlantic City” to take over. As a kid he “always drew” and worked three summers as a caricaturist on Atlantic City’s Million Dollar Pier.

Jerry Lieberman says he originally “wanted to be a doctor,” and he endured two years of pre-med before allowing all the “fantasy, other-world head aspects involved in growing up in corny, carny, show-biz pizzaz-zy Atlantic City” to take over. As a kid he “always drew” and worked three summers as a caricaturist on Atlantic City’s Million Dollar Pier.

He admired John Hubley’s Moonbird (1960) and Saul Bass’ titles and he constructed his own make-shift 16mm camera stand to “experiment with stop-motion, and even some professional work for WCAU-TV in Philadelphia doing promos for a local kids’ show.”

After studying design and graphics on a scholarship to the Philadelphia Museum’s School of Art, and a brief stint in the Army, Jerry came to New York City in 1964. “My first year in New York,” says Jerry today, “I made a storyboard six feet by ten feet long with 200 panels. It was my portfolio and it used to knock people over when I unfolded it.”

He managed to get work right away doing animated films for NBC-TV’s Exploring, “but I learned success doesn’t come easy. There were times when I walked the pavements going from one local production house to another for six months before getting work. One time my portfolio was so severely criticized by one potential employer, I stopped seeing people and had a phobia about work and my talent.

“I worked very hard; I paid my dues; eventually I made a lot of money in a short time and went to Europe. I thought foreign influences might be good for my work.” In London, Jerry met George Dunning who told him “the best place to go for work is Italy.” In Rome, Jerry was hired by American Harry Hess, a former UFA animator, and he worked for a year doing storyboards, design and animation for Italian commercials both in Rome and Milan. He even acted in a few live-action beer commercials.

Jerry returned to America with an excellent reel and his next big break was to be hired by Jack Zander at Pelican Productions as a designer. “Because animation does include every form of art, I wrote to Lee Strasberg and asked to join the Actor’s Studio Directors Unit, and I was accepted and studied there for two years. After a year at Pelican, he freelanced on educational films and was, for a short hilarious time, Phyllis Diller’s painting instructor.

“In 1968, Art Petricone, Howard Basis and I got together and started Ovation Films, Inc.,” says Jerry. “Howard and Art met at Kim and Gifford, and I had worked with Howard on a job. We started our business during the decline of the ‘Golden Years’ of TV commercial production, but we didn’t know that at the time. We had our reputations, things built up slowly, and in March of ’76 we’ll have been in business for eight years.”

Ovation is one of the top commercial houses on the East Coast, a successful studio whose award-lined walls attest to their excellent work done for clients who include Eastern Airlines, Volkswagen, Levis, American Cancer Society, Clairol, and Children’s Television Workshop. At first, duties at Ovation were sharply defined, with Jerry doing designing, Howard handling the animation, and Art the super salesmanship, but today Jerry explains that “each of us get involved in producing and directing different commercials. Sometimes we work separately, sometimes we work together. We are now doing a little live-action work, and we are interested in doing a feature animated cartoon. Creativity, budgets keep getting tightened up, but we manage to maintain quality in our product.”

In 1973, Jerry enjoyed “a great personal success,” as La Cinematheque Quebe-coise directrice Louise Beaudet describes it, at the Annecy Animation Film Festival. “His films were so American and he looked so American when he took a bow that he was a big hit with the French,” says Madame Beaudet. Ovation’s Yes My Sweet took a prize at Annecy that year, as their Parrot and the Plumber had at Zagreb the year before.

“I admire live-action directors who are interested in the visual aspects of film,” says Jerry as he ticks off the names of favorites Warhol, Fellini, Russell, and Hitchcock. “But I love animation because you have to be so multi-talented and involved in so many fields. It’s very demanding, always a challenge, and very satisfying.”

- For a short period in 1973, I worked for Phil Kimmelman’s studio PK&A. I was an Asst. Animator alongside Larry Riley. We had a brilliant time for a period, until work got a bit shy. The studio was very tight, and the mood was one of searching for the highest quality. Rowland Wilson was a designer of many of the Schoolhouse Rock pieces I assisted on. Phil was a pleasant guy to have for a boss, and I certainly enjoyed the experience.

He retired a few years back, but he’s back producing more Schoolhouse Rock episodes for Disney. I’m glad to see it.

Jerry Lieberman was someone I came into contact with frequently. We never worked together. Somehow I think he always saw me as a rival – I don’t know if that’s a reality, but it’s my perception. The last couple of times I met him he was directing theater and loving it.

Animation &Rowland B. Wilson 29 Nov 2007 09:05 am

Jack Schnerk

- I apologize for the server problems we had yesterday. Our site was down for most of the day. If you haven’t seen yesterday’s post, just scroll down.

- Jack Schnerk‘s daughter, Mary Schnerk Lincoln, has put three of her father’s commercial sample reels onto YouTube . This gives me a good excuse to call attention to his work, once again. There are a number of well-known and collector’s item commercials in these reels. Included are spots designed by the likes of Gahan Wilson, Tomi Ungerer, Charles Saxon and Rowland Wilson.

- Jack Schnerk‘s daughter, Mary Schnerk Lincoln, has put three of her father’s commercial sample reels onto YouTube . This gives me a good excuse to call attention to his work, once again. There are a number of well-known and collector’s item commercials in these reels. Included are spots designed by the likes of Gahan Wilson, Tomi Ungerer, Charles Saxon and Rowland Wilson.

Jack Schnerk was a great animator who deserves considerably more attention. He was a strong influence on me in the first eight years of my career and taught me quite a few large principles about the business. He also told me a few stories of his work as an assistant at Disney’s on Bambi and Dumbo as well as the great times animating at UPA and the difficulties of animating at Shamus Culhane’s studio. Actually, he didn’t tell me about his problems with Shamus; another animator did. Jack complained about the business, but never about how he was treated.

I wish I had more samples of the many scenes of his that I assisted. He worked in a very distinct style – I don’t think I’ve seen anyone elseever draw that way. Somehow, the very rough drawings weren’t hard to clean up, and he didn’t leave the bulk of the work for the people following him. He was concerned about the timing and did every drawing he needed  to make sure that timing worked. Most of the time we worked together, he had no chance to see pencil tests. Only on Raggedy Ann did he have that luxury.

to make sure that timing worked. Most of the time we worked together, he had no chance to see pencil tests. Only on Raggedy Ann did he have that luxury.

Jack had a dark side, that I appreciated, but he also brought a lightness and individual sensibility to the work he did. He took chances in his animation and timing and sometimes failed but usually succeeded with them. That’s more than I’ll say for most of the animators I’ve met in the business.

See Jack Schnerk sample reel 1.