Category ArchiveIndependent Animation

Articles on Animation &Independent Animation 17 Jul 2009 07:40 am

Bob Godfrey Interview

Here’s an interview with Bob Godfrey by John Cannon pulled from Animafilm 2/1979.

John Cannon: What do you think of animation as a specific category of film art? What are its capabilities and limitations?

Bob Godfrey: My answers to it vary with the kind of mood I’m in. It is a very small part of film art and has tremendous capabilities and many, many limitations. One of the reasons for the present state of the industry is that we are not enough aware of the limitations of the medium that we are in. There are lots of things that animation cannot do or shouldn’t do and we seem to be doing them.

Bob Godfrey: My answers to it vary with the kind of mood I’m in. It is a very small part of film art and has tremendous capabilities and many, many limitations. One of the reasons for the present state of the industry is that we are not enough aware of the limitations of the medium that we are in. There are lots of things that animation cannot do or shouldn’t do and we seem to be doing them.

JC: Such as?

BG: The things that live-action handles terribly well like Ingmar Bergman, … personal relationships. In fact live-action is moving into areas that should really be our areas like “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” or “Star Wars”. Animated film should go into the impossible, the fantastic, into the mind of man, because the live-action camera has been literally everywhere it can ___________Bob Godfrey

go on earth — it’s even been to the moon. It’s getting

extremely difficult to amaze people. What cinema has to be into is.

FANTASY AND SPECTACLE. To do spectacular things in animation on a big screen costs a lot of money, a high risk with the decline of the short film, which I lament terribly – the short film is slowly being strangulated by the people who run our business, the distributors. There are no short films exhibited in the principal market, the United States, and very few short films shown here. There’s the old adage “if you want to lose money make a short” and that dies hard in Wardour Street. You can’t get the money to make shorts. Nobody goes to the cinema to see a short – they go to see a long.

So we as animation producers are being forced (if not forced some of us are going willingly) into one of two areas; television with commercials of forced into making longer films, the long feature-length animated film. One has to think very long and very hard before venturing into this area. Judging by the films I’ve heard about or seen recently we are not coming up with the ‘smash hits’ and unless you’re a smash hit your’re nothing; there’s no longer a place for a B feature. We’re not coming up with the ‘smashes’.

So we as animation producers are being forced (if not forced some of us are going willingly) into one of two areas; television with commercials of forced into making longer films, the long feature-length animated film. One has to think very long and very hard before venturing into this area. Judging by the films I’ve heard about or seen recently we are not coming up with the ‘smash hits’ and unless you’re a smash hit your’re nothing; there’s no longer a place for a B feature. We’re not coming up with the ‘smashes’.

JC: Why not?

BG: Wrong subjects perhaps. Perhaps it should be for the children’s market here. Children are catered for by Walt Disney but I don’t know many other children’s producers. I want to make a children’s musical because I think it’s a good idea, because when you’ve outgrown one audience, in another seven years there’s another coming along.

I don’t say that animation should cater solely for children of the family audience. Look at the work of Ralph Bakshi – he works for the young teenage market, the biggest audience we have, the young people who don’t want to sit at home at night.

There’s been a whole spate of animated films recently from the West Coast of America and I don’t think any one of them has really been the

‘smash’. It shouldn’t be to difficult – at least we’ve got to do something to our audience: if we can’t amaze them, perhaps we can still make them laugh, make them cry. You must engage your audience’s emotions and possibly animation is failing in this.

THE ENTREPRENEURS. In animation tend to be the artists — artists in the sense of an artistic background – and perhaps these aren’t the right people to communicate with audiences. One must be a showman first and an artist second, like Disney. He had the great faculty for giving people what they wanted, whereas today there seems the great tendency for self-indulgence on the part of animation producers. It’s what they want first and what the public wants second. It’s a strong temptation for anybody working in animation.

JC: Can animation still hold the audience? BG: Yes, more than anything. We’re just wasting the medium – a sameness is coming over. There’s a tremendous desire to do a quality product after all the conveyor-belt type stuff we’ve had over the last few years.

There’s reaction against that and a strong desire here in London and the West Coast of America to do the quality product. Against that there is the lack of mone’y, the sheer cost of producing an animated film. We’re exploring ways – that’s what “Great” was, an economical way of doing something at the same time as keeping it moving and keeping it entertaining. In these respects it’s successful – it only cost ‘£ 36,00 to make, not a lot for a half-hour animated musical.

It’s good to continue with the musical but we need good stories… maybe animation’ought to be yanked out of art schools and put into drama schools. That would be a start. There are far too m%y artistic considerations and not enough dramatic or story-structure considerations, that is the trouble. We must rethink plus the fact we have no tradition to fall back on.

JC: Has there been no tradition at all? Where do you place the old ‘classics’ of America animation?

BG: The Disney films and Fleischer films came out of the short tradition. The animation house on the side of the big American distributors.

JC: They all had to have a house cartoon?

BG: Yes, Warners, UA and that sorl Everyone on the side of the live-action Out of this came the “Silly Symphonies the longer things. Disney is the only one his place with long animation films. Af Disney moved to live-action which si way he was going anyway; he moved “Jungle Book” which was terrific for me. There was another lull after his death and suddenly came up with “Yellow Submarine.”

BG: Yes, Warners, UA and that sorl Everyone on the side of the live-action Out of this came the “Silly Symphonies the longer things. Disney is the only one his place with long animation films. Af Disney moved to live-action which si way he was going anyway; he moved “Jungle Book” which was terrific for me. There was another lull after his death and suddenly came up with “Yellow Submarine.”

JC: Which was a shot out of the blue?

BG: I don’t think it changed anything at all. It was certainly a milestone. We talk about before “Yellow Submarine” and after “Yellow Submarine”.

A very important and good film but somehow synonymous with swinging London, the Beatles, 1967, 1968 and now it doesn’t seem to matter so much, it’s history. It changed nothing because we all suddenly went back to making things that came before it.

BAKSHI’S HAPPENED – a phenomenon. He has tremendous energy and makes more features than dogs have fleas. He does a great amount of work. He’s now doing “The Lord of the Rings.” All he does is interesting. He’s a fantastic foree in our world, extremely good for the industry. We rush to see his latest films here. He’s taken animation out of the slightly infantile area of pigs in sailor hats and animated nursery-rhymes. He’s made it into the urban nightmare… Look at the New York of “Hoppity Comes to Town” and compare it with, say, “Heavy Traffic” and there’s great sociological comment there. It reveals what has happened to a city in thirty years and what has happened to attitudes. Bakshi has brought animation up to date and one must admire him for that. He’s not had a ‘smash’ yet but I hear amazing stories of “The Lord of the Rings” and it being Bakshi whatever I hear, I believe. He’s the saviour of the West Coast. Box-office success it what it’s all about.

JC: Could critics help animation?

BG: You have drama critics, ballet critics, opera critics. You don’t really have animation critics. This is a great pity. I never see an animated film really criticized properly.

JC: Who could do that?

BG: Someone who knows something about animation. We work in a subject there’s a lot of ignorance about. It’s always handled by the run-of-the-mill film critic. We need an Apollinaire, someone to write about us from the inside, perhaps a failed animator turned journalist… We do need some penetrating analysis right now. Animation, because of animation festivals, is terribly incestuous. At festivals – the only place we meet nowadays — we’re

PREACHING TO THE CONVERTED and in a way the pressures on animation have reduced it to the sort of sameness. The days of the house-style of a few years ago have gone. There’s kind of faceless uniformity about it now.

The advertisers have forced their styles onto us here whereas in the past they had to have our style or leave it. There is still a Disney style, they’re the only ones who can afford it and they don’t make commercials.

JC: Haven’t commercials been of positive use beyond keeping some animators is business? BG: It’s a two-edged sword. On balance it has done more harm than good. Well, they’ve kept us alive. We have to look for alternatives although there are studios completely dedicated to producing animation for commercials who would not want to do anything else.

Halas and Bachelor try to get away. I probably do more entertainment than anyone else in Britain. Richard Williams has his films, “Raggety Ann and Andy”. He built up the Pink Panther tradition too when it was fashionable to have expensive titles. In “Charge of the Light Brigade” the animation said it all, I don’t know why we needed the live action! But financial recession has slammed the door of artistic titles in our faces.

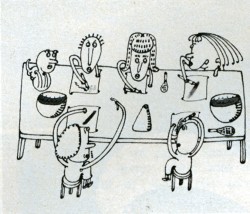

All images are from Godfrey’s film, GREAT.

JC: What doors are opening?

BG: Well, the National Script Development Fund have given me money to work out a package to do an animated feature. I have made a couple of successful animated shorts that prove that you can make money out of them, but I don’t want to keep on trying to prove it. It’s too exhausting.

Having proved it, I’m doing one last short with Vladko Grgic in Yougoslavia which I think will possibly be the best short I’ve been associated with. I’d like to take a

HOLIDAY FROM SHORTS. I’ve done more than most people – and get into the longs. I feel I’m equipped to do it because of the two series which were the equivalent of four hours of animation, a hell of a lot. I’m venturing now into a new area for me. I hope I don’t catch a cold.

One must now think internationally. The film “Jumbo” is set in England and New York so this gives it the transatlantic appeal. The trouble with “Great” was it was so English; no-one understood it.

JC: But it won an Oscar?

BG: It won an Oscar but it’s never been distributed in the States; they’ve never heard of Brunei and they’ve only just heard of Queen Victoria. I blame the distribution system. It’s no good making an animated film unless you have good links with a distributor. JC: But,,Great” was fortunate in Britain? BG: It was fortunate in that it was commissioned by British Lion who subsequently went bankrupt… not solely because of “Great”! You must have the guarantee of distribution before you start anything.

JC: What is it like working in Britain now?

BG:. It’s a bit like Dickens, a best of times and a worst of times. It’s amazing now we keep going. One reason it that British animators are among the best in the world – I say that not to bang the drum or rattle the sabre — I believe that. “Yellow Submarine” helped to bring on a generation of, talented animators, mostly spread out in little tiny companies. I’d hate to see them go down because of escalating costs, rents, etc…

IT’S A TERRIBLE STRUGGLE we have to go on, for some there’s nothing else. We’re attracting more work from abroad – France and Germany. I’m working on “Sesame Street” for Kuwait, Nigeria. Africa is opening up – one door shuts, another door opens. I have to keep my ear to the ground and move with the times. The markets and patterns change all the time, but we are still keyed to the side of the advertising industry.

JC: How should animation be taught?

BG: I teach in an art school one day a week and I am anti-art school and pro-drama school. We must avoid the artistic self-indulgent area. I’m guilty of this too because I financed the films myself and why the hell shouldn’t I?

The cult of the director is something out of Europe — not America where one had the great commercial directors who until recently no-one had ever heard of. In the 1960′s they were re-discovered and the French began saying isn’t Howard Hawks marvellous, which of course he was, or Ford, or Wyler. Nobody said the films were great because they directed them. It was out of Europe that we got the ‘artistic’ film and the cult of the director which has been shipped in animation over to Canada which rarely makes it into the commercial cinema.

JC: Are the new technologies offering any new opportunities for animation?

BG: You mean the great video-tape breakthroughs that are always going to happen? The computer animation that will take over the world? It never happens. Basically it is produced now as BY FLEISCHER ALL THOSE YEARS AGO, equipment’s a lot better and we’re standardizing more. There are more and more animation rostrums in London. Let’s hope they all keep busy.

JC: What about animation and television?

BG: Animation goes into television through commercials and is well paid but animation for programmes is poorly paid and consequently we’re not doing well there. The “Muppets” work — they’ve effected the compromise between instant live action and the sheer labour of animation which makes it impracticable for instant television. Television is instant; animation isn’t. Perhaps the demarcations are natural.

Animation belongs in the cinema where we can afford to labour longer and spend more – for television we can’t produce it fast enough or economically enough.

I’ve never liked puppets very much — I’m not exactly a puppetteer – I love Trnka puppets and Pojar but it doesn’t seem to belong in this country; rather in Poland, Russia, Czechoslovakia where there are such marvellous tradition of puppet work. The “Muppets” however, who grew out of “Sesame Street” are superb, really funny. The “Sesame Street” tradition has helped get work on the small screen. I don’t know how we can solve

the major problem though of the very badly paid area of animation for television programmes. That’s why most of the animation on television is of so low a standard, but what can anyone do with a microscopic budget?

JC: We’ve talked of financial limitations a great deal. What of the other limitations?

BG: Animation is still the art of the impossible; it should concern itself with this but so has live action recently. “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” does this and this is what makes it so mind-boggling. It wouldn’t have been believable as animation as it would lose credibility.

People see animation and do not find it offensive. “It’s a doll” or “it’s a cartoon”. We can make dogs talk. We should deal in imaginative situations. My students don’t really think cartoon. They think live-action and you’ve got to really work on them to think like a cartoonist. A lot of students will have a hand come on the screen and move something. I ask “why the hand?”; it’s simple, acceptable cinematic trick to make the thing move by magic. You must condition yourself to the world of Melies, he was so wonderful because he did tricks.

JC: But your persona is not so much a trickster on screen but an everyday ordinary bloke?

BG: Oh, the Stan Hayward/Bob Godfrey syndrome. Yes, he’s your everyday standard man, with a blown mind. His fantasies are extra-ordinary and this is what I’m doing now. My elephant is ordinary – well he’s not ordinary, he’s the biggest elephant in the world – but his fantasies are amazing. It’s the coming together of the fantasy world and the real world. A mad person cannot differentiate between the two; the two worlds merge. But some people, like “Henry 9 Till 5″ keep fantasy in one compartment and reality in another. I like working with Stan Hayward: he’s one of the few people who’s bothered to sit down and think what animation is all about.

JC: How do animators benefit from film festivals?

BG: The thing about festivals is to realise the background against which those films are produced. How difficult it is for Bruno Bozzetto in Italy? What are the difficulties in Czechoslovakia, Moscow, Yugoslavia? You and I are going to Poland so we’ll find out what things are like there. How do animators function UNDER STATE SUBSIDY? There’s a lot more corning here insofar as a lot of the work I do now is short information films for the Central Office of Information. Does the Canadian Film Board work? – yes, because we get wonderful animators like Caroline Leaf. Without the Film Board a woman like Caroline would not get the opportunity to come through and carry on her experiments. There’s nothing like it anywhere else.

In Britain we’ve got the National Film School now which is supposed to be working well and the London International Film School and the arts schools and colleges. A lot of the people working in London are old student of mine from Farnham and Guildford and are moving in. I suppose one person in three gets fixed up in the industry from school. One minute everybody is working, then the film finishes, and everyone is out of work and a great nebulous mass of people move round trying to get absorbed on other things – like musicians here moving form gig to gig, band to band.

JC: Can you tell us something about your new project, “Jumbo”?

BG: It’s a pilot. If I hadn’t done “Great” I wouldn’t be doing “Jumbo”. HE WAS A BIG ELEPHANT, who was around in the nineteenth century. I don’t make films about the nineteenth century through choice. I seem to get lumbered with them. Other people might say I’ve got a size fixation; the smallest man in the world making the biggest ship in the world and now the biggest elephant in the world.

I read Professor Bill Jolly’s book, bought the film rights and applied to the National Script Development Fund and was very lucky and got allocated the money last August. I’m now trying to get the pilot together. I think you always start by trying to make the film the same way as the one you’ve just finished , so I tried to get the old team off “Great” together again, some times with success. With my films there is a sort of continuity. I always start off with making the last one all over again and somewhere through it changes — thank God it changes, otherwise I’d be making the same film through all over again!

“Great” was made in an incredibly disorganised way because it was the first long film I’d ever made. I have to be organised now because we’re only paid to develop the script. So, for my £10,000, I have to produce a story-board, ten to fifteen musical numbers and lyrics and a screenplay. I’m story-boarding with one of my great artists Anne Jolliffe; music is being done by Johnnie Johnson; Colin Pearson who did the lyrics for “Great” is doing the lyrics. It’s a little bit of the old team but learning from our mistakes in the last one.

It’ll run for seventy-five minutes. We’ve got this awful, almost surrealist fact that the elephant got run over by a train and although I’ve been advised to leave it out as it might disturb children I can’t. I’m haunted by this poor beast’s death and I’ve got to put it into the story whether it kills me at the box-office or not. To me why Jumbo is immortal and famous is not because he was big but because he was run over by the train. I’ve tried to make it as funny as I can and have shifted it up to the front of the film. Death can be humorous, it doesn’t have to be incredibly tragic. One of the great twentieth century phobias is death. We’ve had the sexual hang-up and luckily we’re talking or screwing our way out of that one. Death? Why not? Stan Hayward’s making funny films about death and kids go “bang, bang, you’re dead” all the time. If we keep it at that superficial level and at the front of the film so that the kids don’t get too attached to the elephant I think we’ll get away with it.

It is important Jumbo dies. Brunei dies. I seem to be getting stuck with people who die at the high point of the film. Jumbo gave his name to the dictionary, he is synonymous with everything big, enormous, large and wonderful, It’s the story of a simple, everyday, neighbourly elephant who becomes a star, a world-beater, a blockbuster if you like.

I’m at the story-board stage now. I have a love-hate relationship with this stage of a film, it’s the most difficult part of the film after the story – the rest is just shovelling coal. It’s hard work but THE IDEA MAKES THE STORY and this underlines all I’ve been saying in the interview. If the story’s not right you can do all the most brilliant animation in the world and it’s not going to work. The idea must be right.

by John Cannon

Frame Grabs &Independent Animation 05 Jun 2009 07:28 am

Bruno’s Allegro 2

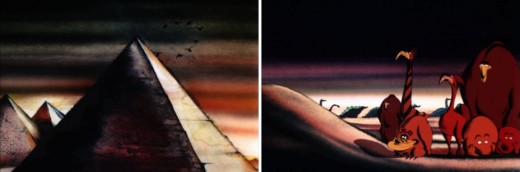

- Ravel’s “Bolero” continues in Allegro Non Troppo, and Bruno Bozzetto‘s extraordinary musical sequence moves on. Prior to seeing this film for the first time, I knew Bozzetto’s work well. I had seen many of his shorts and was a big fan. He never failed to have a big comment on society while making incredibly funny films. They were extraordinarily rich gems.

- Ravel’s “Bolero” continues in Allegro Non Troppo, and Bruno Bozzetto‘s extraordinary musical sequence moves on. Prior to seeing this film for the first time, I knew Bozzetto’s work well. I had seen many of his shorts and was a big fan. He never failed to have a big comment on society while making incredibly funny films. They were extraordinarily rich gems.

This film, however, was a surprise. The writing, as usual, was brilliant. The animation was more fluid, the styles were more varied and the calibre of each piece was very high. Of course, I should have expected masterful work from a master. It still holds up well on the little TV screen – and I’m sure it’s as strong in a theater (having seen it projected no too long ago.)

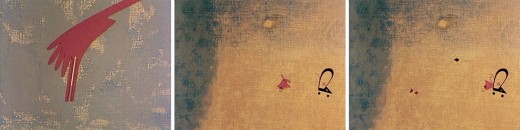

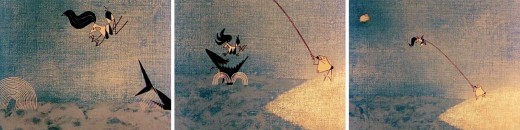

Here are the remainder of the frame grabs for that sequence.

52

52(Click any image to enlarge.)

return to live action

Animation &Art Art &Independent Animation 22 May 2009 08:34 am

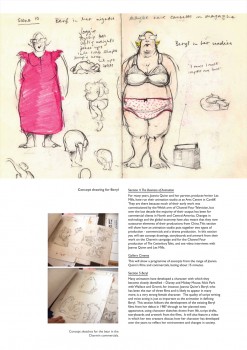

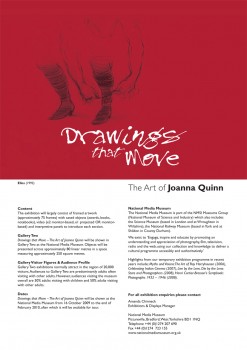

Quinn & Schnall

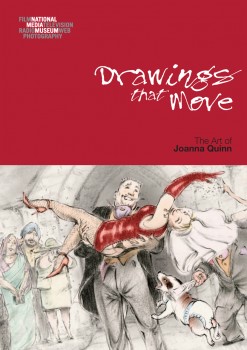

- Here’s a booklet that Karl Cohen sent me, the catalogue of an exhibition of Joanna Quinn‘s stunningly beautiful drawings for the National Media Museum in Bradford, West Yorkshire. This show will be held from October 16, 2009 – February 21, 2010. The catalogue has me watering at the mouth and gets me wondering if I can visit this show.

Perhaps there’s some venue in the US that would be interested in proogramming something so attractive and valuable.

Take a look at this catalogue:

(Click any image to enlarge.)

________________________

- The ever-creative John Schnall sent me a video of a recent piece he did. As a film, it’s pure promo but as a creative endeavor it’s pretty sensational. I thought I’d like to share, so here it is: Glympse.

Animation Artifacts &Daily post &Independent Animation 07 Mar 2009 08:55 am

Flow charts and Robert Breer

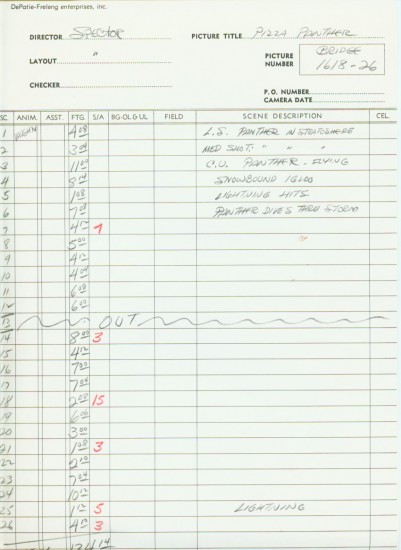

- After my several posts on Exposure sheets, I am planning to write a short piece on the scene folders used at the various studios. These, in a way, are works of art in their own right.

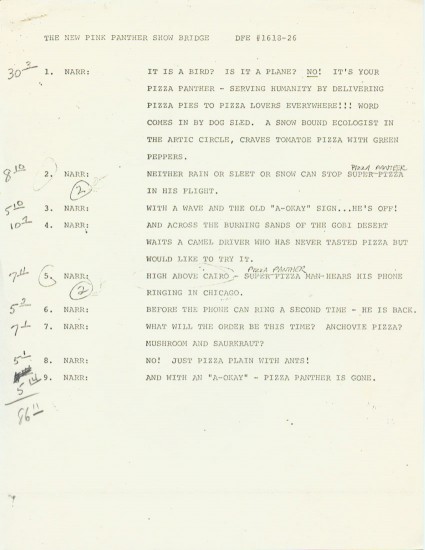

However, Paul Spector sent me something that I talked about quite a while back. When a short or a longform film is done, the amount of paperwork that’s prepared to keep things organized becomes immense. There’s an awful lot of bookkeeping.

All the scenes get numbered, all the sequences get numbered, all the drawings get numbered to correspond to the scene and sequence numbers.

With all those sequences and scenes, you start needing a chart to be able to tell one from the other. Disney’s “Drafts” are a precursor to these. This is what Paul’s sent from his father, Irv Spector‘s collection. It’s a flow chart for some scenes from a Pink Panther short done for DePatie-Freleng. The corresponding page of the script is posted below it.

It looks like they ran out of scene descriptions in the heat of the production and just concentrated on the numbering. John Hubley, I remember, as being the absolute best for scene descriptions. One or two words would completely capture the scene. In the Carousel feature, there were hundreds of scenes, yet you could always tell one from the other. The chart wasn’t done on 8½x11 or 14, but was done by hand on oaktag and pasted in the main I&P room. Using that one or two word caption, you could synthesize the scene you were searching for, and it made a lot more sense than searching for scene C129a or whatever.

(Click any image to enlarge.)

Thanks to Paul Spector for this great example of a flow chart.

__________________________

Tonight!

Don’t forget that Sita Sings the Blues is on ch 13 tonight

in the New York area at 10:45pm.

__________________________

- And now for something completely different.

The Animated World of Robert Breer

Sunday, March 15, 2009, 10:30 a.m.

At The Noguchi Museum

This free event for children between the ages of 2 and 12 and their families, features an hour-long program of short films by artist and filmmaker Robert Breer followed by art-making activities. Breer, who has been at the forefront of American avant-garde cinema since the 1960s, is a painter and sculptor who turned to animation to create a unique and amazing body of work. Introduced by David Schwartz, Moving Image Chief Curator, Breer’s playful and lively films will engage the entire family and provide a new point of entry from which to view and explore Isamu Noguchi’s work. Following the screening, Noguchi Museum educators will be present to facilitate activities and art-making projects. Families are encouraged to bring a snack and kick back while they enjoy the films. See below for a full list of titles.

This free event for children between the ages of 2 and 12 and their families, features an hour-long program of short films by artist and filmmaker Robert Breer followed by art-making activities. Breer, who has been at the forefront of American avant-garde cinema since the 1960s, is a painter and sculptor who turned to animation to create a unique and amazing body of work. Introduced by David Schwartz, Moving Image Chief Curator, Breer’s playful and lively films will engage the entire family and provide a new point of entry from which to view and explore Isamu Noguchi’s work. Following the screening, Noguchi Museum educators will be present to facilitate activities and art-making projects. Families are encouraged to bring a snack and kick back while they enjoy the films. See below for a full list of titles.

Free admission, but reservations are required. To register, send an email to: smurphy@noguchi.org with your family’s name, the number of attendees and preferred form of contact (phone or email) or call 718.204.7088, extension 203.

The Noguchi Museum is located at Vernon Boulevard between 10th St and 33rd Rd in Long Island City. Sunday shuttle-bus service is available between Manhattan and the Museum.

The following films will be screened:

- Homage To Jean Tinguely’s Homage To New York (1960, 9 mins.) This record of the birth and death of Tinguely’s famous auto-destructive sculpture at MoMA is itself a sculptural work, through its camera and editing techniques.

Fuji (1973, 8 mins.) Rotoscoped images of Mount Fuji, as seen from a train, are blended into the magical dreamscape of this lyrical voyage.

Swiss Army Knife With Rats and Pigeons (1981, 6 mins.) Images from everyday life are intercut with abstract and imaginary shapes in this virtuoso collage of drawings and live action photography.

Bang! (1986, 10 mins.) TV images of a boy paddling a boat, an arena crowd cheering, flowers, phones, and a wide array of personal doodle, photos, and assorted images whiz by in this mayhem-filled gem.

ATOZ (2000, 5 mins.) In this film dedicated to his daughter, Breer uses humor—along with a frog, planes, and other shapes—to look at the impact of the ordered alphabet on a child’s awakening mind.

Trial Balloons (1982, 5 mins.) One of Breer’s most lyrical films, Trial Balloons combines home movies with animation and hand-cut traveling mattes.

What Goes Up (2000, 4 mins.) The richness and the impermanence of life are captured in this rapid-fire animation of images capturing the joys of family and work life, and of food, drink, nature, and love.

Articles on Animation &Independent Animation 25 Nov 2008 08:37 am

The New Animators of 1977

- Jenny Lerew reminded me, this past weekend, of Richard Protovin. Richard was an Independent animator and the head of NYU’s animation department from 1979-1988. In that position, he inspired quite a few people, and Jenny’s comment got me trying to remember where I saw an article about Richard.

I came up with this article by Thelma Schenkel from the animation issue of Millimeter Magazine in 1977. I got a kick out of revisiting this article and thought it definitely should be shared.

A new generation of American animators is coming into existence. Trained in art schools and college filmmaking programs, they are turning to animation on a scale unprecedented in independent American filmmaking of the past. Mainly in their 20′s and 30′s, they were brought up on comic and storytelling cartoons, but their films are rarely broadly comical, although they’re often very witty, nor are they illustrations for stories. They are staking out a new territory for animation, one that until recently was the province of the poet. Whether their films are erotic, whimsical, or abstract, they are all in some way exploring the inner landscape — feelings, the workings of the mind, the mechanisms of perception. Although the techniques they use vary widely, they all share in the poetic impulse — in the search for new expressions of personal visions.

Until fairly recently, only a few names came to mind when one thought of experimental poetic animation in America. Today, the ranks of talented young animation poets are growing. Despite the dearth of effective distribution channels and outlets, and the difficulties of finding time and mental space to make their “personal films,” while often supporting themselves by doing commercial projects, they are making some very exciting, extraordinary films. The following are only a few of the many talented young animation artists whose films merit being seen and re-seen, talked about, and written about:

ELIOT NOYES, JR. — Since Clay, made at Harvard’s Carpenter Center in 1964, Noyes has been dazzling audiences of all ages with his witty inventiveness, his bold handling of materials, and his humanism. In Clay, an 8-minute version of evolution, he spawns a universe out of a lump of clay with the playfulness of the ancient gods of creation. Noyes makes magic with the simplest materials: Alphabet (1966, Canadian Film Board) is drawn on milk-glass with felt-tipped pen; In a Box (1966), a tale of the barriers people and cities erect to keep out beauty and freedom, is drawn on paper; Sandman (1973) (Pictured below right) creates a dream world with an underlit handful of sand. His most ambitious film, The Dot (1975), combines live-action and animation in a half-hour allegory on the liberating

ELIOT NOYES, JR. — Since Clay, made at Harvard’s Carpenter Center in 1964, Noyes has been dazzling audiences of all ages with his witty inventiveness, his bold handling of materials, and his humanism. In Clay, an 8-minute version of evolution, he spawns a universe out of a lump of clay with the playfulness of the ancient gods of creation. Noyes makes magic with the simplest materials: Alphabet (1966, Canadian Film Board) is drawn on milk-glass with felt-tipped pen; In a Box (1966), a tale of the barriers people and cities erect to keep out beauty and freedom, is drawn on paper; Sandman (1973) (Pictured below right) creates a dream world with an underlit handful of sand. His most ambitious film, The Dot (1975), combines live-action and animation in a half-hour allegory on the liberating  power of the imagination — the animated dot becomes the catalyst that frees the “prisoners” from the confines of school and home. Constantly exploring new techniques, Noyes is currently completing Glove Story, using actors in combinations with video-animation, and Pitcher’s Feathered Bird, which experiments with chromakeying live actors into Noyes’ drawings. If his brilliant use of technique, his wit, and the humanism of his films of the last 14 years are any indication, we can look forward to an innovative, compassionate, and refreshing use of videotape when these tapes are released.

power of the imagination — the animated dot becomes the catalyst that frees the “prisoners” from the confines of school and home. Constantly exploring new techniques, Noyes is currently completing Glove Story, using actors in combinations with video-animation, and Pitcher’s Feathered Bird, which experiments with chromakeying live actors into Noyes’ drawings. If his brilliant use of technique, his wit, and the humanism of his films of the last 14 years are any indication, we can look forward to an innovative, compassionate, and refreshing use of videotape when these tapes are released.

GEORGE GRIFFIN‘s self-referential films explore the tricky territory of animated illusion with marvelous wit and ingenuity. Paradoxical though it may seem, he often uses the most rudimentary of pre-cinematic toys — flip-books — to explore the most modern of ideas. Trikfilm No. 3 (1973), a complex orchestration of flip-pad metamorphoses alternating with the creation of the same sequences by the artist, combines live-action with animation, all the while delightfully fragmenting the illusion it is creating. The most elaborate of his “anti-cartoons,” as he calls them, is Head (1975), (pictured below left) an ingenious, witty essay on making filmed, photographed, drawn, painted, and Xeroxed images move.

Reverberating between multi-media versions of the same events, playing with disjunctions between figure and ground, Head is “a trick-film meditation on portraiture; the animator, as actor, lives through his drawings, which in turn become actors who influence his own self-image.” An insider’s diary on the process of creation, Head is a brilliant encyclopedia exploration of the circular relationship between the animator and his creation, of the nature of animated illusion itself. L’Age Door (1975), a one-minute flip-book film about a man and a door, shows what a witty intelligence can do with just a memo pad and a pen. His most recent work, View-master (1976), drawn in parodied cartoon styles, is comprised of 8 circular drawings with 12 characters in a run cycle on each drawing. The characters, including a troupe of dancing headless waiters and a selfpropelled shoe, chase each other around until the full circle of characters is revealed at the end — a contemporary Zoopraxiscope, with Eadweard Muybridge’s running man at the center, Griffin’s tribute to one of the greats of pre-cinema. In his witty elaborations on the simple techniques of pre-cinema, Griffin is unique among young experimenters in animation today. Informed by the refreshing playfulness of film’s 19th century origins, his films are very much of the 20th and even 21st centuries, in their incisive and witty insights into the nature of time, perception, and what we call “reality.”

Reverberating between multi-media versions of the same events, playing with disjunctions between figure and ground, Head is “a trick-film meditation on portraiture; the animator, as actor, lives through his drawings, which in turn become actors who influence his own self-image.” An insider’s diary on the process of creation, Head is a brilliant encyclopedia exploration of the circular relationship between the animator and his creation, of the nature of animated illusion itself. L’Age Door (1975), a one-minute flip-book film about a man and a door, shows what a witty intelligence can do with just a memo pad and a pen. His most recent work, View-master (1976), drawn in parodied cartoon styles, is comprised of 8 circular drawings with 12 characters in a run cycle on each drawing. The characters, including a troupe of dancing headless waiters and a selfpropelled shoe, chase each other around until the full circle of characters is revealed at the end — a contemporary Zoopraxiscope, with Eadweard Muybridge’s running man at the center, Griffin’s tribute to one of the greats of pre-cinema. In his witty elaborations on the simple techniques of pre-cinema, Griffin is unique among young experimenters in animation today. Informed by the refreshing playfulness of film’s 19th century origins, his films are very much of the 20th and even 21st centuries, in their incisive and witty insights into the nature of time, perception, and what we call “reality.”

KATHY ROSE‘s insignia is the remarkable cast of “characters” who people her films and who can be traced through The Mysterians (1973), The Moon Show (1974), Mirror People (1974), and The Doodlers (1975), all made at California Institute of the Arts. In The Mysterians, her silly-putty creatures, capable of any transformation imaginable, begin playing their surrealistic metamorphic games — which become more complex in Mirror People, as the figure-ground manipulations reveal space to be as much of an illusion as corporeality. To a sound-track of fun-house screams and cackles, Mirror People, a tribe of Halloween hallucinations, fuse into each other and get absorbed into their reflections and their environments in a universe where all is flux and nothing is stable,

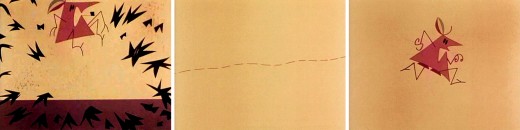

KATHY ROSE‘s insignia is the remarkable cast of “characters” who people her films and who can be traced through The Mysterians (1973), The Moon Show (1974), Mirror People (1974), and The Doodlers (1975), all made at California Institute of the Arts. In The Mysterians, her silly-putty creatures, capable of any transformation imaginable, begin playing their surrealistic metamorphic games — which become more complex in Mirror People, as the figure-ground manipulations reveal space to be as much of an illusion as corporeality. To a sound-track of fun-house screams and cackles, Mirror People, a tribe of Halloween hallucinations, fuse into each other and get absorbed into their reflections and their environments in a universe where all is flux and nothing is stable,  except for the constant delights of metamorphosis. The Doodlers (pictured Right) carries the game of illusion still further. Through Miss Nose and her clan of doodlers, whose curvilinear outlines and splashes of color come to life through a magic cat’s-tail brush, Rose makes some witty observations on the art of animation and on the symbiotic relationship between the artist and the characters. Although she was very excited by the films of Yoji Kuri, whose surrealistic pranks are echoed in her films, Rose’s characters have an indescribable uniqueness. It might have something to do with the way she draws them: all her characters are drawn upside-down. Yes. When she creates them, it is as if she wanted someone sitting on the other side of the table to be able to see them rightside-up, without having to turn the drawing around (of course, when they are filmed, they are rightside-up). She finds that it’s like “drawing with the eyes closed, you have one less level of consciousness.” But only the characters are drawn that way; the constant swirling changes of perspective, the simulated camera movements — all require tighter control and are drawn rightside-up. The battles and games between Rose’s characters are at some level intra-psychic encounters; she sees her characters as “parts of my unconscious” and is currently working on a film in which she and her characters confront each other. She feels that the new uses of animation have to be more than personal. They have to have an “inner truth about something real, a truth people can feel.” In their delightfully whimsical way, Rose’s films about the joys and struggles of creation succeed in conveying that truth.

except for the constant delights of metamorphosis. The Doodlers (pictured Right) carries the game of illusion still further. Through Miss Nose and her clan of doodlers, whose curvilinear outlines and splashes of color come to life through a magic cat’s-tail brush, Rose makes some witty observations on the art of animation and on the symbiotic relationship between the artist and the characters. Although she was very excited by the films of Yoji Kuri, whose surrealistic pranks are echoed in her films, Rose’s characters have an indescribable uniqueness. It might have something to do with the way she draws them: all her characters are drawn upside-down. Yes. When she creates them, it is as if she wanted someone sitting on the other side of the table to be able to see them rightside-up, without having to turn the drawing around (of course, when they are filmed, they are rightside-up). She finds that it’s like “drawing with the eyes closed, you have one less level of consciousness.” But only the characters are drawn that way; the constant swirling changes of perspective, the simulated camera movements — all require tighter control and are drawn rightside-up. The battles and games between Rose’s characters are at some level intra-psychic encounters; she sees her characters as “parts of my unconscious” and is currently working on a film in which she and her characters confront each other. She feels that the new uses of animation have to be more than personal. They have to have an “inner truth about something real, a truth people can feel.” In their delightfully whimsical way, Rose’s films about the joys and struggles of creation succeed in conveying that truth.

AL JARNOW‘s films, which seem to be playing with the malleability of perspectival logic, with fluctuations between the subjective and objective viewpoints, have a marvelous sense of spatial humor. At times reminiscent of Escher’s disorienting figure-ground enigmas, his films often lead us through an architectural nightmare (he studied architecture at Dartmouth), but manage, through the integrity of their visual logic, to create a spatial universe which seems to make perfect sense. Rotating Cubic Grid (1975) and Four Quadrant Exercise (1975) are marvelously precise architectural games, but Auto Song (1976), his most elaborate “story” film, pushes the play between subject and object the furthest. Drawn on index cards, it narrates the journey of an invisible eye (Jarnow’s) from its (invisible) reflection in the mirror of a VW bug, across impossible highways and oceans, up stairs and through tunnels, ending in the black hole of space. Purposely starting with a recognizable image set in recognizable space, the film very soon goes off into its own space which, because we have been well teased from the beginning, we accept without question. Jarnow’s latest film, Shorelines, combines objects (shells, stones), live-action pixillation, drawings, and Xeroxes. Although it represents a move away from the draftsman’s precision of the earlier films, it continues to play with space and perspective in Jarnow’s inimitable way.

DENNIS PIES‘ early films, Nebula and Merkaba (both made at California Institute of the Arts in 1973), which he calls “experimental graphics,” already manifest his preoccupation with cosmic, mystical imagery. In Aura Corona (1974), he improvises a dance of two vertabra-like creatures which develope auras, depicting the delicate evolution of animate forms in a haunting, suggestive way. Pursuing his exploration of organic abstraction, in Luma Nocturna (1974), the “dark twin of Aura Corona” exquisitely nuanced crystalline textures float and fuse in a kind of lyrical, ecstatic cosmic dance. All done without the use of the

DENNIS PIES‘ early films, Nebula and Merkaba (both made at California Institute of the Arts in 1973), which he calls “experimental graphics,” already manifest his preoccupation with cosmic, mystical imagery. In Aura Corona (1974), he improvises a dance of two vertabra-like creatures which develope auras, depicting the delicate evolution of animate forms in a haunting, suggestive way. Pursuing his exploration of organic abstraction, in Luma Nocturna (1974), the “dark twin of Aura Corona” exquisitely nuanced crystalline textures float and fuse in a kind of lyrical, ecstatic cosmic dance. All done without the use of the  optical printer, the effects in Pies’ films are reminiscent of the work of Belson and Whitney, influences he readily acknowledges. He is currently working on Sonoma (pictured right) (an Indian word meaning “Valley of the Moon” — the general area in California where Pies lives), which deals with material from his journal of the last year. It is shot in 35 mm. color negative and is fully animated, “the full image in constant flux.”

optical printer, the effects in Pies’ films are reminiscent of the work of Belson and Whitney, influences he readily acknowledges. He is currently working on Sonoma (pictured right) (an Indian word meaning “Valley of the Moon” — the general area in California where Pies lives), which deals with material from his journal of the last year. It is shot in 35 mm. color negative and is fully animated, “the full image in constant flux.”

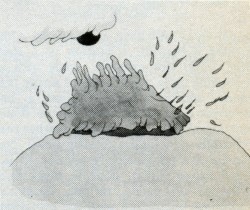

MARY BEAMS made her first animated film, Tub Film, in 1972 at Harvard’s Carpenter Center, where she now teaches. A whimsical view of a bath from a bather’s perspective, done in rough line drawings on paper, Tub Film ends with a slurp as the woman disappears down the drain,  after the cat pulls the plug. Seed Reel (1975), a series of 3 sexual haikus, is done in the same rough outline style: in “Hungry Poem,” (pictured Left) (reverse printed with white lines on black), a penivorous flower devours its mate and swells into a pregnant belly; “Sniff and Lick” portrays the encounters of some very erotic flowers, and “12 Dancing Penises” dance to the tune of “Turkey in the Straw.” In Going Home Sketchbook (1975) and Paul Revere Is Here (1976), she experiments with rotoscoping and shows her deftness in handling a technique that, in other hands, can become tedious, but which for Beams becomes an exciting way of recapturing the spontaneity of the hand-drawn image.

after the cat pulls the plug. Seed Reel (1975), a series of 3 sexual haikus, is done in the same rough outline style: in “Hungry Poem,” (pictured Left) (reverse printed with white lines on black), a penivorous flower devours its mate and swells into a pregnant belly; “Sniff and Lick” portrays the encounters of some very erotic flowers, and “12 Dancing Penises” dance to the tune of “Turkey in the Straw.” In Going Home Sketchbook (1975) and Paul Revere Is Here (1976), she experiments with rotoscoping and shows her deftness in handling a technique that, in other hands, can become tedious, but which for Beams becomes an exciting way of recapturing the spontaneity of the hand-drawn image.

ADAM BECKETT, of California Institute of the Arts, feels that “we are at the beginning of a wonderful golden age of animation”; his innovative, unconven-tional films will have a lot to do with making it happen. Evolution of a Red Star (1973), for example, made with a 6-drawing cycle which evolved under the camera during a 6-week period, is an excellent example of what can be done with a convention — the cycle — when the principles of painting directly under the camera are imaginatively applied to it. Flesh Flows (pictured Right) (1974), done in black line drawings on paper, reflects Beckett’s continued fascination with the

ADAM BECKETT, of California Institute of the Arts, feels that “we are at the beginning of a wonderful golden age of animation”; his innovative, unconven-tional films will have a lot to do with making it happen. Evolution of a Red Star (1973), for example, made with a 6-drawing cycle which evolved under the camera during a 6-week period, is an excellent example of what can be done with a convention — the cycle — when the principles of painting directly under the camera are imaginatively applied to it. Flesh Flows (pictured Right) (1974), done in black line drawings on paper, reflects Beckett’s continued fascination with the  evolution of polymorphous matter. Animated male and female body parts flow into, around, and through each other, evolving into proliferating, multiform creatures in a surreal pulsating dance. Beckett is currently trying to combine work on Life in the Atom (which he has been working on for 7 years), a new version of Dear Janice, and Knotte Grosse with his commercial work.

evolution of polymorphous matter. Animated male and female body parts flow into, around, and through each other, evolving into proliferating, multiform creatures in a surreal pulsating dance. Beckett is currently trying to combine work on Life in the Atom (which he has been working on for 7 years), a new version of Dear Janice, and Knotte Grosse with his commercial work.

RICHARD PROTOVIN‘s films have a naive, story-book quality about them which is definitely not what they’re about. This soft, innocent front, the delicate lines and candy-colored pastels, is an intentional disguise to arouse expectation for a simple story, expectations which he astutely manipulates for very different ends — “to turn things around, to go on the other side of the mirror.” Flamingo Boogy (1974), drawn on paper, starts out in a drive-in movie and ends up in a flock of flamingoes and winged turtles embracing the sun. The ocean itself is drawn into the sun in the mythical epiphany that ends the film. Everything flows and pulsates at the same time, disturbing movement echoing “opposites coming together in a spiritual union.” Heyzeus (1975), reflecting Protovin’s interest in Tantric Yoga, is an orgiastic dance of phallic and vaginal creatures which culminates in the creation of a

Left – Richard Protoviin/self caricature Right – “Flamingo Boogy”

mysterious bird creature exuding a powerful mystical energy. Like so many experimental animators, Protovin plays on the expectations associated with cartoons, only to turn them upside-down in an unexpected haunting way.

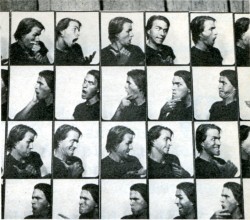

KATHLEEN LAUGHLIN‘s films explore a wide range of techniques: saturated color printing in A Round Feeling (1970), stop-motion single framing in Opening/Closing (1972) and Susan Trough Corn (1974). Her recent film Madsong (1976) (pictured Right) combines animation and live-action in a young woman’s personal everie on being female. With a polyphonic voice track (the woman’s inner voices echoed by the chorus of voices outside), it parallels the flow of her unconscious with the movement of the cycles of nature. In its artful use of live-action/animation overlap, which echoes the agitated flux of the voices of her mind from fantasy to reality, from “inside to outside, from backward to forward simultaneously,” Madsong is one of the few films about women today that succeeds in being intensely personal and univeral at the same time. Laughlin is currently working on a film about Meridel Le Seuer, a 76-year old midwestern poetess.

KATHLEEN LAUGHLIN‘s films explore a wide range of techniques: saturated color printing in A Round Feeling (1970), stop-motion single framing in Opening/Closing (1972) and Susan Trough Corn (1974). Her recent film Madsong (1976) (pictured Right) combines animation and live-action in a young woman’s personal everie on being female. With a polyphonic voice track (the woman’s inner voices echoed by the chorus of voices outside), it parallels the flow of her unconscious with the movement of the cycles of nature. In its artful use of live-action/animation overlap, which echoes the agitated flux of the voices of her mind from fantasy to reality, from “inside to outside, from backward to forward simultaneously,” Madsong is one of the few films about women today that succeeds in being intensely personal and univeral at the same time. Laughlin is currently working on a film about Meridel Le Seuer, a 76-year old midwestern poetess.

MAUREEN SELWOOD — The delicate lyricism of Maureen Selwood’s style is already evident in her first film, The Box (1969), which combines live-action and animation in a lively fantasy of the Astor Place cube sculpture coming to” life. The Six Sillies (1971), made at New York University’s Institute for Film and Television, in 35 mm eel animation, is rich with the luscious color and delicate Matisse-like line that evolve in the public service and commercial projects she has done since then.

MAUREEN SELWOOD — The delicate lyricism of Maureen Selwood’s style is already evident in her first film, The Box (1969), which combines live-action and animation in a lively fantasy of the Astor Place cube sculpture coming to” life. The Six Sillies (1971), made at New York University’s Institute for Film and Television, in 35 mm eel animation, is rich with the luscious color and delicate Matisse-like line that evolve in the public service and commercial projects she has done since then.

In her current project, Odalisque (pictured Left), she moves away from story-tellling into poetry; a series of mythical women undergo the most extraordinary transformations — the kinds of dreamlike metamorphosis that Selwood’s lyricism brings to life beautifully.

The short post script as to where are they now is not going to be written by me. I know that a couple of these people have died (Richard Protovin & Adam Beckett), several are still animating (Dennis Pies and Eli Noyes are both in California), others are animating and are connected with excellent schools (George Griffin teaches at Pratt, Maureen Selwood at CalArts). I believe Al Jarnow still lives in NY state, and the last I heard of Thelma Schenkel, she was teaching at Baruch College in NY. I’m not sure of the rest.

If any of you reading this know more, I urge you to let us know in the comments section or I’ll be glad to write a more extended piece in the future. I’m already thinking about some of the Independent animators from 1977 who were left out of this article.

Frame Grabs &Independent Animation 30 Sep 2008 08:06 am

Zagreb’s Ersatz

- When a 35mm print of The Four Poster entered Yugoslavia, it got lost for two weeks. A group of young animators hijacked the print to study the John Hubley directed animation sequences, done at UPA. Suddenly, these young animators found their calling and watched the film to drain every drop of it. The end result was a new animation studio, Zagreb, which put style and content above animation and gave a new life to modern graphics in animation.

- When a 35mm print of The Four Poster entered Yugoslavia, it got lost for two weeks. A group of young animators hijacked the print to study the John Hubley directed animation sequences, done at UPA. Suddenly, these young animators found their calling and watched the film to drain every drop of it. The end result was a new animation studio, Zagreb, which put style and content above animation and gave a new life to modern graphics in animation.

Ersatz was a film done in 1961 which took America by storm and won the Oscar that year. Dusan Vukotic’s short was the first non-US flm to win this prize. When the film came out, I wasn’t its greatest enthusiast. I’d seen so many more daring shorts, graphically speaking, and found the film slow moving and a bit annoying. Of course, looking back on it, now, when graphics are so pathetic in animation and the animation is even worse, Ersatz looks pretty good.

I’ve pulled some frame grabs to give an idea of the film. These are they.

1

1(Click any image to enlarge.)

Articles on Animation &Commentary &Guest writer &Independent Animation 12 Jul 2008 08:23 am

Guest writer: Why Cartoons?

– I received the following article from Nina Paley, the creator/animator/ director/designer of Sita Sings the Blues (which won the Best Feature Prize at Annecy this year.) The article came with a letter, which I think helps explain why she wrote it.

– I received the following article from Nina Paley, the creator/animator/ director/designer of Sita Sings the Blues (which won the Best Feature Prize at Annecy this year.) The article came with a letter, which I think helps explain why she wrote it.

Here’s the letter:

- Hi Michael,

I’m back in NY, finally, spending my first day home in my apartment with the AC on with the cat next to me, surfing the web. I read your review of Wall-E, which I haven’t seen yet, and thought to send you this essay I wrote for Frederator (which they never used) on the theme of “Why Cartoons?”.

Since Berlin, I’ve been convinced that most cinemagoers are simply voyeurs, craving simple stimulation of their primate visual senses in the form of close-up views of beautiful people courting and mating, and gory violence. Things our inner primates think about constantly but seldom get to see. Animation is more abstract and cerebral, visually. I prefer it to live action, but I am a freak (like most animation fans).

Pixar’s success lies in making animation that visually resembles live-action and satisfies the typical cinemagoer’s inner voyeur. Hence the expanding popularity of 3D “animation” among Hollywood producers.

Typical American cinemagoers are put off by 2D animation, but 3D gives them more of what their primate eyes want: to believe they’re watching real events up close without risking personal exposure.

Since I’m going to a lot of festivals with “Sita,” I am struck by the cultural differences between animation festivals and “real” film festivals. When I refer to films as “live-action,” most directors don’t know what I’m talking about; to them live-action is just “film,” and animation is completely off their radars. Most have never heard of Annecy or any other animation festivals. Most film festivals automatically exclude animation from competition, instead programming it in what I call the Animation Ghetto – or worse (in the case of “Sita”), the “Family” or “Children’s” sections. But their programming animation at all is evidence of some progress. And I’m grateful, especially for the 2D animation fans that already exist, and the chance to expose new viewers to the art form.

Hope you’re well,

–Nina

This is the article she sent.

- WHY CARTOONS?

Because less information = more meaning

Animation takes advantage of quirks of human perception. Good cartoons lie somewhere between nature (no abstraction) and text (full abstraction).

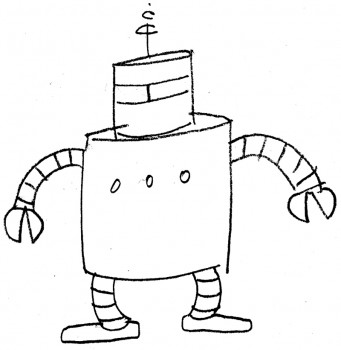

At its best, animation does what live action can’t. Good animation is unrealistic. This starts with the style itself: drawings and designs of things that can’t exist in the real world. Exaggerated heads and hands, huge or tiny eyes, rubber-hose limbs, cubism. A handmade line drawing of a robot requires our uniquely human imaginations to understand it as “a robot,” but we may recognize it more quickly than a photograph of a real robot.

Exhibit A: cartoon drawing of a robot.

Animated motion should also defy reality. For example, bouncy walks that no robot (or human) could replicate, even though we can recognize them as “walks.” Good cartoons stimulate and exercise our imaginations in ways live action never can.

Like reading or working out, viewing cartoons can be exhausting. But far less time is needed to communicate more meaning. That’s why cartoons are so effective as shorts (and commercials).

Live action conveys too much information. “High production values” are the art of removing as much information from nature as possible.

Wrinkles and blemishes on actors’ faces are concealed with makeup; stray threads and hairs are tucked away by stylists; wires and microphones hidden through camouflage, meticulous set design and framing; unwanted details lost in shadows via careful lighting, which heightens only those few areas and outlines intended to convey meaning. But still, excessive information abounds in live action.

Cartoons start with only the information needed. There’s nothing extraneous to hide. If you mean “eyes,” you show a symbolic short-hand representation of “eyes,” nothing more. No gunk in the corner of the eyes, no moles on the eyelids, no eyebrow dandruff – unless you explicitly intend to convey these details as well. The picture is as clear as the idea in the mind of the artist, and that clarity of meaning is transferred to the viewer.

Exhibit C: real eye, belonging to the author.

Notice bloodshot veins indicating stress, wrinkles indicating wisdom and maturity,

shiny skin surface indicating absence of makeup, and other excess information.

(Also, producing animation totally trumps live action: No uppity actors. No obnoxious crew. No permits. No tedious laws of physics. If you can imagine it, you can animate it; no extra charge.)

But animation remains the bastard child of cinema. Most moviegoers just want to watch beautiful people. Bonus if the beautiful people are celebrities; extra bonus if the beautiful people are performing sex or violence onscreen. Animation can deliver meaning, story, ideas – but it doesn’t satisfy the sexual voyeur that drives most cinephiles. In live action, a camera can linger for minutes on a beautiful actress’ face, as the audience attends to all that information: every eye-blink, every change in pupil dilation, the subtlest nostril flare, the slightest movement of any of the hundreds of facial muscles lurking below the makeup. In live action, such a scene is watchable. How could such a serious and pensive scene be conveyed in animation? It would either be painfully dull (a long still) or ridiculous (imagine a Bill Plympton interpretation where every nuance is exaggerated: small nostril flare becomes huge, facial muscle twitch becomes twitchy animal running around under skin) and, like all animation, exhausting.

Live action satisfies our voyeurism, animation ridicules it.

Since I can’t take voyeurism seriously, I go for ridicule.

Animation &Commentary &Independent Animation 11 Jul 2008 08:03 am

John Schnall

- I’d like to talk about a film, but actually it’s not the film but the filmmaker that I’m interested in.

A couple of weeks ago, Mark Mayerson wrote a piece on his blog about Animation and Theater. Mark has become something of an authority on acting and animation. This piece was, in ways, an extension of past comments he’d made about the subject. Having attended a one-man show about Theodore Roosevelt, which was entitled “Bully,” Mark discussed the possibility or the likelihood of animation pulling off such a subject with as much success.

This made me think about the subject that has fascinated me for years. Animating long monologues with any such success. A year or so ago, I’d gone through a number of theatrical monologues thinking I’d have an actor record the piece (or pieces) and try getting them to work. Using animation as a medium to delve beyond the surface to understand character and characterization. One thing leading into another, I never got to complete that project – though I haven’t given up on it.

This made me think about the subject that has fascinated me for years. Animating long monologues with any such success. A year or so ago, I’d gone through a number of theatrical monologues thinking I’d have an actor record the piece (or pieces) and try getting them to work. Using animation as a medium to delve beyond the surface to understand character and characterization. One thing leading into another, I never got to complete that project – though I haven’t given up on it.

Now I find, thanks to a correspondence with John Schnall that he has done this.

John is one of the more daring animators/animation directors out there. He has for years chosen difficult subjects and difficult projects to animate. They all have a strong sense of the bizarre, but they’re all breaking molds that I don’t see others even trying to break.

His most recent film, Dead Comic, is as difficult as it gets. The film is a monologue by a dead comedian, and it offers a gruesome exploration of the afteryears of someone married, eternally to his job. The film could have been called Dead Animator, in my case, but it wouldn’t have been as funny. John has animated a monologue – a difficult monologue.

The film is so difficult that audiences seem to be afraid of it. (Is the subject of death that difficult?) The recent ASIFA-East festival didn’t have the patience even to sit through it, though, in my opinion, it’s better than most of those that won prizes. It’s just more challenging, and the audience wanted more of the expected rather than something complex and difficult.

I don’t think it’s the greatest film of all time, but I do think it’s brilliant. You should watch it and understand that the staging is incredibly complex, the timing is very sharp and the design and writing are wholly original and unafraid. it took hard effort, knowledge and ability to make it work.

I don’t think it’s the greatest film of all time, but I do think it’s brilliant. You should watch it and understand that the staging is incredibly complex, the timing is very sharp and the design and writing are wholly original and unafraid. it took hard effort, knowledge and ability to make it work.

In any case, I am always eager to see what John is up to. He’s one of the few artists working in New York and in Independent animation.

Go to John Schnall‘s website here.

See Dead Comic here.

Buy a 40 min. compilation of John’s films here.

The last two illustrations are from Ha Ha Ha and The Binding of Isaac.

Daily post &Festivals &Independent Animation 25 Mar 2008 08:16 am

Local Talent

- It’s nice to see some local talent get good press for their animation work. Currently, The New York Observer has a solid article about Emily Hubley in conjunction with the screening of her feature film, Toe Tactic, at the New Directors/New Films festival held at MOMA and Lincoln Center.

- It’s nice to see some local talent get good press for their animation work. Currently, The New York Observer has a solid article about Emily Hubley in conjunction with the screening of her feature film, Toe Tactic, at the New Directors/New Films festival held at MOMA and Lincoln Center.

Here’s a short quote from the informative article:

__ Originally, there wasn’t going to be any animation at all in the film. But Ms. Hubley hand-

__ drew the dogs (with some help from animator Jeremiah Dickey) to help shepherd the

__ short poems about love, life and mortality into the movie. “At the beginning [of the

__ process] the dogs are just a joke, but then they nosed their way into the rest of the

__ story,†she said. “Poetry is one thing that is very hard to put into movies… I just thought

__ that the only way to keep it fun, or keep people from glazing over, or I guess to keep it

__ from being too self-loving, would be turning it into something else completely.â€

__ All together, the result is a highly emotional fable. “I want [the audience] to feel full

__ when they walk away,†she said. “It’s really about personal art; it’s not a factory

__ product.â€

As I reported last week the film’s stars include: Lily Rabe, John Sayles, Marian Seldes, Eli Wallach, Andrea Martin, and Mary Kay Place. Ms. Place and Ms.Martin are two of my favorite performers; John Sayles is the father of Independent Cinema, and I love Eli Wallach. Lily Rabe was brilliant when I saw her in the play, Crimes of the Heart, now playing in New York. What more is there to say.

The film is scheduled to play:

__ Sat Mar 29: 6:00pm (Walter Reade Theater)

__ Mon Mar 31: 9:00pm (MoMA)

- I received some information from the Hiroshima 08 Festival, and was pleased to note that two ASIFA East members are featured.

- I received some information from the Hiroshima 08 Festival, and was pleased to note that two ASIFA East members are featured.

Ray Kosarin is among the International Selection Committee Members. Along with Rao Heidmets from Estonia, Elena Chernova from Russia, Sophie Lodge of the UK, and Kiyoshi Nishimoto of Japan, Ray will represent the US in the selection of films for the festival to be held August 7-11. Add to that information, David Ehrlich, also of ASIFA East, will have a special exhibition and performance for his art. With Paul Driessen as the International Honorary President, the Festival sounds like a big one this year.

Congrats to Ray Kosarin and David Ehrlich.

Daily post &Independent Animation 15 Aug 2007 05:35 pm

Ray Kosarin’s UNCLE

– On Thursday night at 10pm, Ray Kosarin‘s short, Uncle, will premiere on ReelTalk on local channel PBS Thirteen.

– On Thursday night at 10pm, Ray Kosarin‘s short, Uncle, will premiere on ReelTalk on local channel PBS Thirteen.

As I wrote about this short (click here to read) last Saturday, Ray put it out there and said what he thought was important to say, politically, back in 2003 when it wasn’t popular to go against the system. I applaud hiom for that and for the excellent craft in the making of the film.

I sincerely hope you can get the chance to see it.