Category ArchiveFrame Grabs

Frame Grabs &Independent Animation 31 Oct 2011 06:59 am

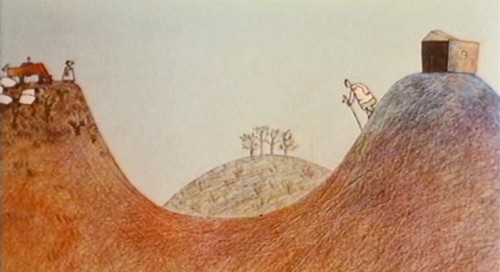

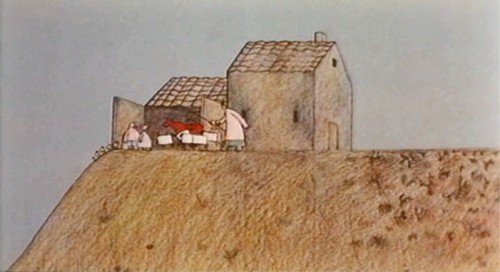

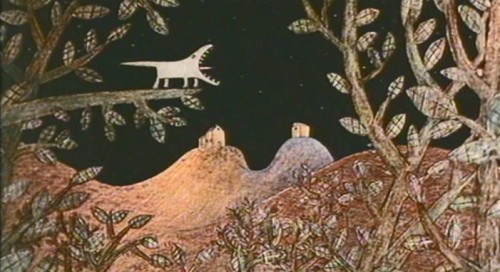

The Hill Farm – 1

- The Hill Farm is one of my favorite films. It was a school project for Mark Baker who burst on the animation scene with this first film. It ended up being the first of three Oscar nominations he’d receive. His second (The Village) and third (Jolly Roger) shorts were also nominated.

He has since formed his own commercial animation studio with Neville Astley, and they were ultimately joined by Phil Davies to form Astley, Baker, Davies. They are jointly responsible for three television series: Peppa Pig, The Big Knights and Ben and Holly’s Little Kingdom.

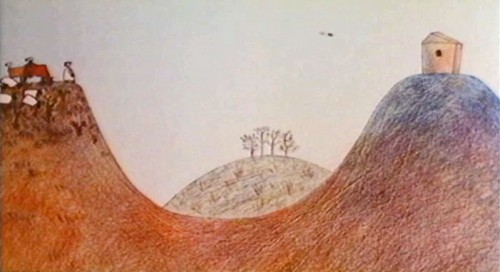

The story of The Hill Farm takes place over three days and shows how the same landscape affects three different sets of people: farmers, campers and hunters. The graphics are beautifully designed and are obviously inspired by a period of Paul Klee’s art. Julian Nott’s score this film, and for all of Baker’s shorts, is just excellent; it couldn’t be better.

The DVD for The Hill Farm can be bought from AWN; it’s packaged with “Gopher Broke” and Plympton’s “Fan and the Flower”.

Here are frame grabs from the first half of the film.

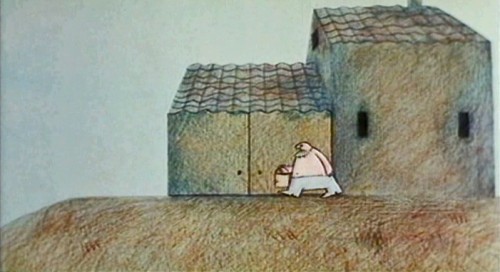

The Farmers:

1

1.

2

2.

3

3The film shows a remarkable sense of professionalism

and knowledge given that it was a student film.

.

4

4.

5

5.

6

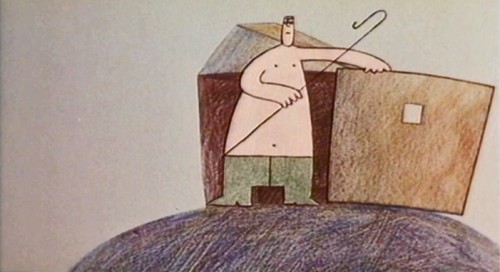

6Time was taken to develop each character in the film.

.

7

7.

8

8.

9

9.

10

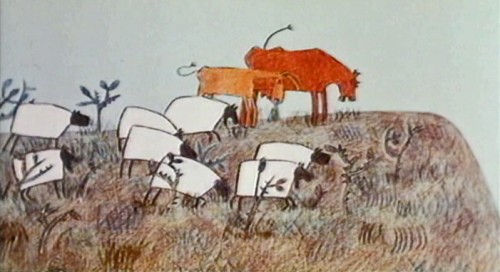

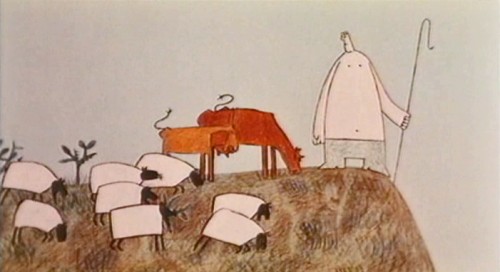

10The animals also take on a character.

.

11

11.

12

12.

13

13.

14

14.

15

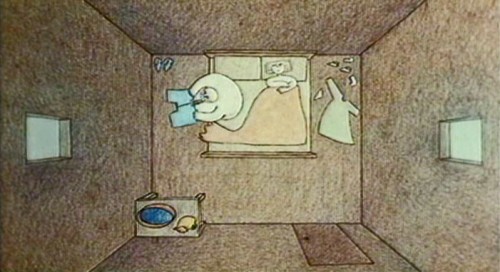

15Mom wakes up Junior – or is it a farm hand?

.

16

16.

17

17.

18

18.

19

19.

20

20.

21

21.

22

22.

23

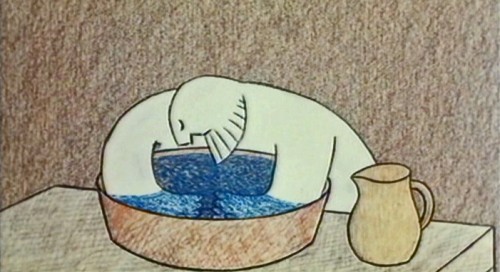

23Junior seems to have some recurring relationship with the bear

who has threatened to eat the sheep.

.

24

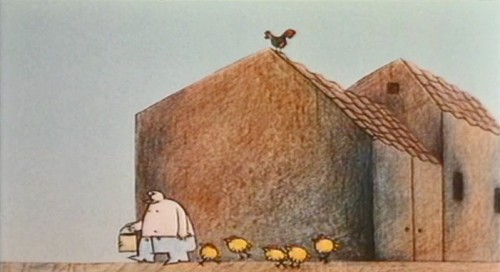

24The pig has his character . . .

.

25

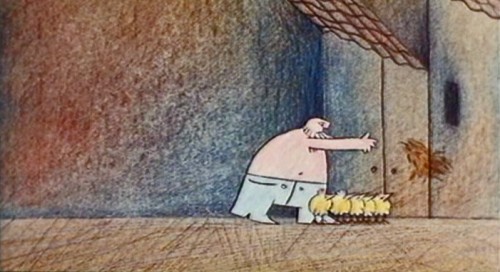

25. . . while the funny and cute chickens are obviously meant for killing.

This gives meaning to all the animals on the farm – as is natural.

.

26

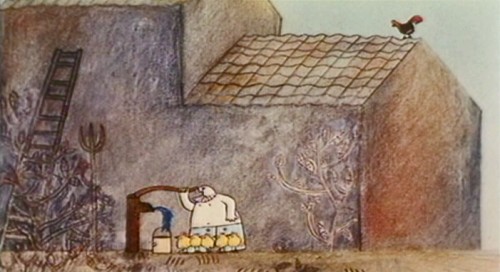

26And they are the prime concern of the farmer.

.

27

27.

28

28.

29

29We are reminded that there are also animals in the wild

other than the threatening bear.

.

Here is a contrasty version on YouTube with some distortion in parts. Part1, Part 2

Animation &Commentary &Frame Grabs 17 Oct 2011 06:57 am

Lantz and Me – recap

In scouting around the internet, I came back to Thad Komorwoski ‘s great piece on Ace In The Hole. It was nice to see these drawings again, and it pushed me back to my own post on the film. I thought I’d bring some attention to that by reposting it, today.

- Like many others, reading the Roger Armstrong reminiscence on Mike Barrier‘s site really got me into the Walter Lantz mood.

I first went back to Mike’s book, The Hollywood Cartoon, and read what info he had about Lantz. After a bit of reading there, I went to look at some of the old Woody Woodpecker shows – I have that collection from Columbia House that came out years ago which includes about three half hour shows per DVD, 10 DVDs, and some beautiful prints.

I first went back to Mike’s book, The Hollywood Cartoon, and read what info he had about Lantz. After a bit of reading there, I went to look at some of the old Woody Woodpecker shows – I have that collection from Columbia House that came out years ago which includes about three half hour shows per DVD, 10 DVDs, and some beautiful prints.

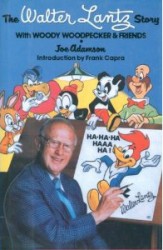

Then I reread one of my all time favorite animation books, The Walter Lantz Story by Joe Adamson. This isn’t a terribly large book, but it sure is packed with a lot of first-rate information.

As an owner of my own animation company I get a real charge in reading about the ups and downs Lantz had to go through, financially, to keep his company afloat. In one chapter, Universal dropped him, and he rebuilt, financing a couple of films with the help of a few animators. Then he went back to Univeral and sold the films to them with a brand new deal. It took enormous entrepreneurial strength believing in what he did and going forward with everything on the line.

It’s a great book, and Joe Adamson should be proud of the effort. I also encourage you all to read it. (If only there were a similar book about Paul Terry.)

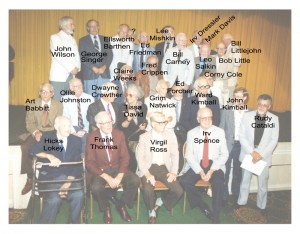

I got to meet Lantz a couple of times in his late years. One was at Grim Natwick’s 100th birthday. Too bad Walter didn’t sit for the group photo; it would’ve added something to the collected group of animation veterans.

The group photo with ID’s alongside this picture.

(Click to enlarge.)

Another event in LA was the Walter Lantz Conference on Animation in which a number of speakers spoke and films were screened. Lantz was everywhere in those few days. It was great.

However, my most memorable meeting came thanks to John Canemaker. John had interviewed and met with Lantz several times during a group of meetings Walter and Gracie were having in New York in the 70s. There was, if I remember correctly, a special screening of their films at which they would talk. Since I was going there, John asked if I wanted to meet up with him and ride to the event with Walter and Gracie in their limousine. It was a treat to meet them one-on-one and to have a chance to share a few words. I have to say he was one of the most kind people I’ve run across, who gave me plenty of chance to talk. It was one of those standout moments in my life.

.

- Back in the day, when I was just a teenager, there was very little in the way of media, as there is today. If you were desperate to become an animator, there weren’t many directions to turn. You had what was on the four or five tv channels that existed and there was the library.

- Back in the day, when I was just a teenager, there was very little in the way of media, as there is today. If you were desperate to become an animator, there weren’t many directions to turn. You had what was on the four or five tv channels that existed and there was the library..

TV offered the Walt Disney show, which two out of four Wednesdays (which eventually moved to Sundays) each month, they’d touch on “Fantasyland”, and you could watch some Disney cartoons – usually Donald and Chip &

Dale, or there was the Woody Woodpecker show, during which Walter Lantz would talk for four or five minutes about some aspect of animation.

Dale, or there was the Woody Woodpecker show, during which Walter Lantz would talk for four or five minutes about some aspect of animation.

For all those other hours of the day when you wanted animation you had to make do with what you could create for yourself.

At the age of 11, I took a part time job for a pharmacist delivering drugs to his clientele.

I lived off the tips that were offered, and I saved my money until I had enough to buy a used movie camera.

The trek into downtown Manhattan was a big one for an eleven year old child, but I loved it. I went by myself to Peerless camera store near Grand Central Station. (It later merged with Willoughby to become Peerless-Willoughby; then it went back to just being Willoughby.)

The trek into downtown Manhattan was a big one for an eleven year old child, but I loved it. I went by myself to Peerless camera store near Grand Central Station. (It later merged with Willoughby to become Peerless-Willoughby; then it went back to just being Willoughby.)

That store, I quickly learned had a large section devoted to films for the 8mm crowd. Lots of Laurel and Hardy, Our Gang and Woody Woodpecker cartoons. Once I had the camera, I saved for a cheap projector and eventually bought some 8mm cartoons.

.

.

Independence. Now, I didn’t have to wait to see them on TV, I could project them myself whenever I wanted. Even better, I jiggered the projector to maneuver the framing device which allowed me to see one frame of the film

at a time, so that I could advance the frames one at a time. I could study animation.

at a time, so that I could advance the frames one at a time. I could study animation.

.

.

I know, I know. I’m describing the stone ages. Today all you have to do is get the DVD (which is incredibly cheap compared to the cost of those old 8mm films) and watch it one frame at a time or any other way you want. And every film is available. If you don’t have it just join Netflix and rent it. Your library is always open and growing.

Yes, Peerless had a large 8mm film division, so you could buy the latest Castle film edition of some Woody Woodpecker cartoon, or you could find many of Ub Iwerks’ films. I had a collection of these. Ub Iwerks was my guy. Everything I’d read about him (in the few books available) got me excited about animation. Actually, Jack and the Beanstalk and Sinbad the Sailor were the first films I’d bought and watch endlessly over and over frame by frame.

Yes, Peerless had a large 8mm film division, so you could buy the latest Castle film edition of some Woody Woodpecker cartoon, or you could find many of Ub Iwerks’ films. I had a collection of these. Ub Iwerks was my guy. Everything I’d read about him (in the few books available) got me excited about animation. Actually, Jack and the Beanstalk and Sinbad the Sailor were the first films I’d bought and watch endlessly over and over frame by frame.

In short time, I knew every frame of Jack and the Beanstalk backwards and forwards. I didn’t realize that it was Grim Natwick who had animated (and directed the animation) on a good part of the film. Meeting Natwick years later, I think I surprised him by saying as much. He just moved on to another subject, appropriately enough.

.

.

In some very real way, I learned animation from that film and several others that I bought in those primitive years of my career. Before I knew principles of drawing, I’d been able to figure out principles of animation. I’d had the Preston Blair book, and I had the Tips on Animation from the Disneyland Corner. I just measured what they said about basic rules and watched – frame by frame – how these rules were executed by the Iwerks’ animators. The rest was up to me to figure out, and I was able to do that.

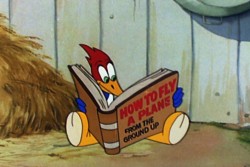

Eventually I bought a Woody Woodpecker cartoon. I was reluctant because so many of them were the very limited films done in the early 60′s – Ma and Pa Beary etc. It took a while to figure out that Ace in the Hole was a wartime movie and the animation would be a bit better. It was also the Woody that I liked – just a bit crazy. So I sprang for it and swallowed that film’s every frame for years.

Eventually I bought a Woody Woodpecker cartoon. I was reluctant because so many of them were the very limited films done in the early 60′s – Ma and Pa Beary etc. It took a while to figure out that Ace in the Hole was a wartime movie and the animation would be a bit better. It was also the Woody that I liked – just a bit crazy. So I sprang for it and swallowed that film’s every frame for years.

I’m not sure who George Dane is, (he seems to have spent years at Lantz before working years at H&B and Filmation) but I studied and analyzed his animation on this film closely and carefully.

I’m not sure who George Dane is, (he seems to have spent years at Lantz before working years at H&B and Filmation) but I studied and analyzed his animation on this film closely and carefully.

The work reminded me of some of the animation done for Columbia in the early 40′s. It had that same mushiness while at the same time not breaking any of the rules. Regardless, he knew what he was doing, and I had a lot to learn from him. And I did.

Things keep changing, media keeps growing. I’m glad I had to fight to get to see any of those old 8mm shorts back in the early years. When I bought my first vhs copy of a Disney feature, it took a while to grasp the fact that I could see every frame of it whenever I wanted. In bygone years, I could only see the rejects that TV didn’t want. I wanted to study Tytla and Thomas and Natwick and Kahl. Instead, I studied George Dane. And you know what, it was pretty damn OK. I learned enough that I knew a lot when I started in the business.

Things keep changing, media keeps growing. I’m glad I had to fight to get to see any of those old 8mm shorts back in the early years. When I bought my first vhs copy of a Disney feature, it took a while to grasp the fact that I could see every frame of it whenever I wanted. In bygone years, I could only see the rejects that TV didn’t want. I wanted to study Tytla and Thomas and Natwick and Kahl. Instead, I studied George Dane. And you know what, it was pretty damn OK. I learned enough that I knew a lot when I started in the business.

I just jumped in and was animating for John Hubley within days of getting that first job. (It helps that it was an open studio like Hubley’s where the individual artist could do anything, as long as he kept his head above water. In most studios there’s a rigidity that keeps you in your classified job.) In fact by then, I was more interested in Art Direction and Direction than I was in animation, but that’s another post.

If you want to learn from the masters, just pop in a DVD and watch it frame-by-frame. If you don’t get a charge out of it, you might begin to wonder if you’re really in the right business. After all these years, I still get the thrill, and I imagine I always will – even from watching Ace in the Hole AGAIN.

Frame Grabs &Hubley &repeated posts 11 Oct 2011 06:54 am

Hubley and the Telephone

- The Hubley show last night was brilliant. A first rate job by John Canemaker. Most of the prints were spotless and beuatiful (something you rarely see with Hubley films – the DVD copies are soft focus and poorly transferred.) I’ll write about it later in the week. I have a lot of photos to add to that post.

I’ve been posting some pieces about the Hubley work. Given the start I had concentrating on it, I can’t come down so quickly. There’ll be a couple more posts on his work this week. This piece is something you won’t see projected any time soon. It’s an industrial done for AT&T originally posted back in July, 2009.

– In 1965, John Hubley directed animation inserts for an educational film for Jerry Fairbanks Productions and AT&T. It’s the story of the history of the telephone and how it works. The story, such that it is, tells about two kids visiting their uncle, an animator (actually, an actor playing an animator). He gives them an animated lecture on the story of the phone.

– In 1965, John Hubley directed animation inserts for an educational film for Jerry Fairbanks Productions and AT&T. It’s the story of the history of the telephone and how it works. The story, such that it is, tells about two kids visiting their uncle, an animator (actually, an actor playing an animator). He gives them an animated lecture on the story of the phone.

The film reminds me very much of another film done by the Hubley studio. UPKEEP was the history of the IBM repairman. We travel through history to see how the repairman has worked over the years. It’s a successful device that works in John’s hands.

The film is available to view on the Prelinger Film Archives. I’ve made some frame grabs to post to give an idea of the style. The characters seem to shift a bit stylistically from the humans at the beginning to those later at the circus. From Hubley to Jay Ward. This was a period where John Hubley was beginning to experiment with more expeditious styles for the jobs that came in. The more artful Maypo style was a bit complicated to pull off. The cels, here, are cel-painted traditionally. (I actually have a hard time believing the date on this film – 1965. It feels more like late 50′s.)

The backgrounds are all by John Hubley, and they remind me of those he would do for UPKEEP and PEOPLE PEOPLE PEOPLE. Lots of white space and soft images. The animation looks like it was done by several people. I recognize Emery Hawkins‘ style, and I also can see Bill Littlejohn in there.

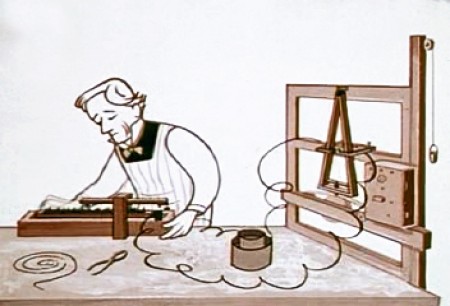

1

1The animator’s studio.

2

2

Kids are always fascinated when an animator draws.

3

3

The character goes from this . . .

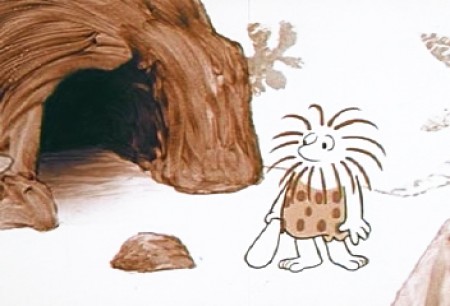

5

5

The caveman has to deliver a message.

![]()

This is the full length of his run, the pan wherein the character

runs from being a caveman to an Egyptian to a Roman.

Here’s the same BG broken into four parts:

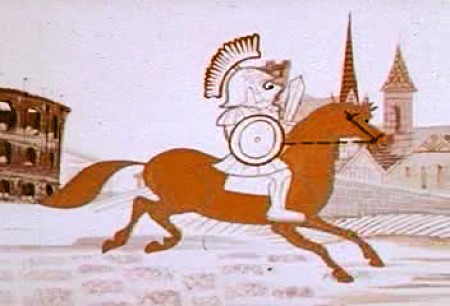

6

6

Once on horseback, man travels through

the middle ages to the pony express.

7

7

Man turns to smoke signals to communicate.

11

11

Morse invents the telegraph.

12

12

Alexander Graham Bell invents the telephone.

13

13

Now the animator explains how the telephone works

to two very interested children. .

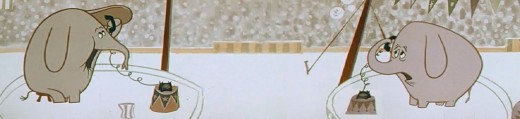

19

19

We get the fable about the lion who calls . . .

21

21

Though he shouts too loudly into the phone.

24

24

Then there’s the squirrel who can dial the phone . . .

25

25

. . . and the bear who answers the phone too late.

Then there’s the elephant who dials the wrong number.

28

28

Finally there’s the pig who won’t get off the phone

so the fox can make an important call.

29

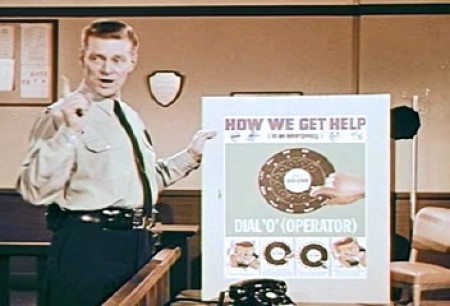

29

Next the animator takes the kids to the police station.

30

30

This way the cop can tell the kids how to make emergency calls.

Commentary &Frame Grabs &Hubley 19 Sep 2011 07:23 am

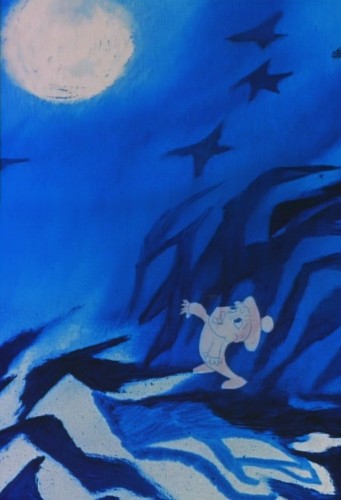

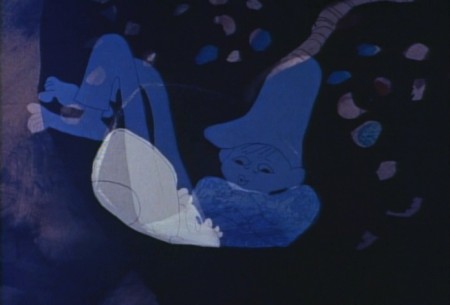

Moonbird

Opening title pan down- Moonbird

- In 1964, John and Faith Hubley‘s film, Of Stars and Men opened at the Beekman Theater in Manhattan. This was their first feature; it was accompanied by a number of their short films. I was in High School, and this is the first time I saw any of the Hubley films, and my life had changed at that screening.

The flat colors of the Disney and Warner Bros cartoons were suddenly replaced with textures. It wasn’t only the backgrounds that had a texture; it was the characters as well. I’d already taught myself quite a bit about animation, but this was something new for me. I sat with saucer eyes watching every element and filmic device John Hubley came up with in creating these flms.

The flat colors of the Disney and Warner Bros cartoons were suddenly replaced with textures. It wasn’t only the backgrounds that had a texture; it was the characters as well. I’d already taught myself quite a bit about animation, but this was something new for me. I sat with saucer eyes watching every element and filmic device John Hubley came up with in creating these flms.

It was so clear that Hubley was using a system of double exposures, doubling the characters in at an exposure of about 60% so that the white paper would be somewhat translucent over the dark backgrounds. The rough pencil lines of the animators clearly delineated the characters in this technique, though they picked up some of color of the Bgs. Obviously, the white paper of the character had been painted black – up to the animator’s lines so that the extraneous parts of the paper was matted out. What a brilliant idea!

It was so clear that Hubley was using a system of double exposures, doubling the characters in at an exposure of about 60% so that the white paper would be somewhat translucent over the dark backgrounds. The rough pencil lines of the animators clearly delineated the characters in this technique, though they picked up some of color of the Bgs. Obviously, the white paper of the character had been painted black – up to the animator’s lines so that the extraneous parts of the paper was matted out. What a brilliant idea!

I explain this process in depth in this post from the past.

.

This enabled us, the audience, to see the rough lines of the animators and brought the same life the Xerox line had brought to 101 Dalmatians. It was thrilling for me.

The sing-song muttering of a child introduces us to “Hampy”.

The rough lines of animator, Bobe Cannon, are a treat on the screen.

Every oil painting background beautiful, alive and modern.

The other amazing thing was that the films used real dialogue.

It didn’t sound like a script. It was obviously, somehow, improvised.

It took me a while to learn how this was done

and what a wonderful way they had of doing it.

Moonbird was different from the other shorts of that period.

Its soundtrack was completely improvised by the

two boys of the Hubleys, Mark and Ray.

. . . but it also used NO music track.

This is very different for the Hubley films that had

such a devotion to the use of jazz on the soundtrack.

The film not only looked different for the time, 1959,

but it sounded different.

This film had clearly been the results of years of experimentation.

After all those brilliant UPA shorts, particularly Rooty Toot Toot.

The original Hubley produced shorts took a new, brilliant turn.

Adventures of an * moved animation forward

in its pursuit of 20th Century Art.

Picasso and Steinberg had been mimicked in the UPA films.

With Adventures of an * the Abstract Expressionists

came under the magnifying glass as John Hubley used

the New York school as his inspiration.

With Tender Game they moved that style into a more emotional

character animation, and by the time they did Moonbird, they

had settled into a very rich style that animation hadn’t noticed.

Two of animation’s finest animators delivered

the brilliant lyricism in this film.

Bobe Cannon, for years, had delivered great animation.

His work with Chuck Jones had produced new and rich

experimental heights particularly in the 1942 short, The Dover Boys.

Hubley had stated that this film was an inspiration

in the move to 20th Century graphics in animation.

Cannon’s work with UPA, both directing and animating,

brought a new sense of poetry to the medium that finally

plays out in this film, Moonbird.

The young Ed Smith rose to great heights

while working for Hubley. His work on Tender Game

showed a natural warmth that spills over in this film.

Animation, double exposures, oil painted Bgs,

improvised voices, no music all pushed this film

to the forefront of animation at the time.

Despite the looseness of the style, it all blends

together as if it had been done by the one artist.

I love the soft airbrushed look Hubley was able

to pull off with much of this double-exposed artwork.

And yet the characters always remain front and center.

A tribute to the two animators and the directoral staging.

This delicate and lyrical film was followed by an anmiated

discussion of nuclear warfare and armament. The Hole

was twice the length and had a political point to make.

The characters’ colors change and fluctuate and sparkle

even as scenes progress, but this all becomes part of

the style which the Hubleys pursued for

the rest of their filmmaking life.

As in Moonbird, the voices in The Hole were improvised

. . . but this time by adults, Dizzy Gillespie and George Mathews.

The Hubleys took their process of improvisation to a new level.

In the end, animation grew up, once upon a time.

The question is whether we’ve squandered that development

and have retrogressed to the 19th Century illustration styles

that Disney pursued. Recently, we seem to have had only

bad drawing or cgi puppets to choose from.

Time to step up, ladies and gentlemen.

Animation &Disney &Frame Grabs 12 Sep 2011 06:34 am

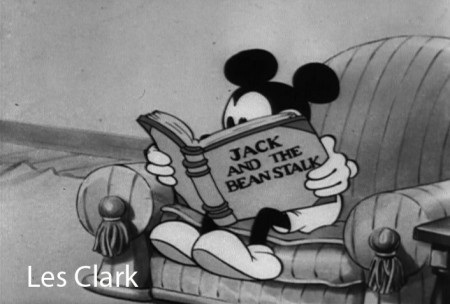

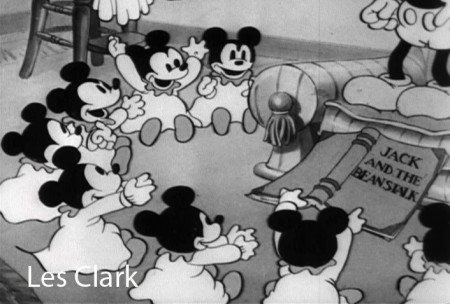

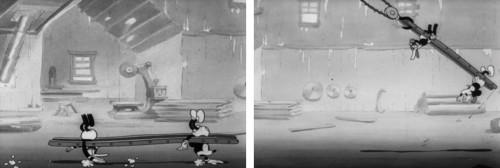

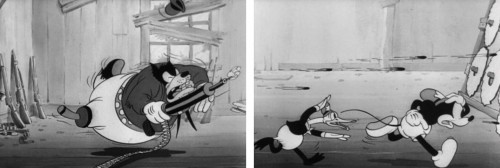

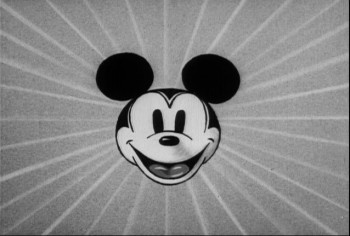

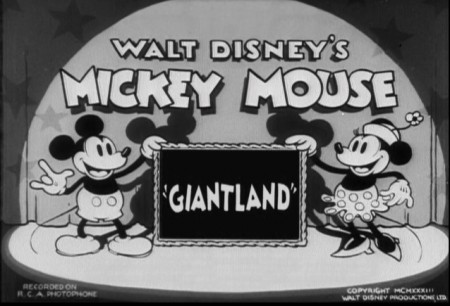

Giantland

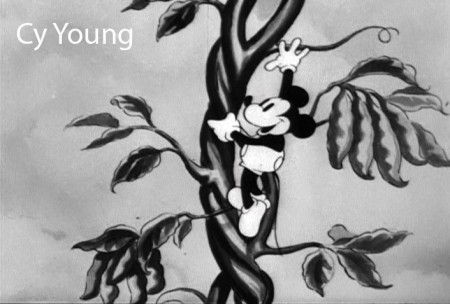

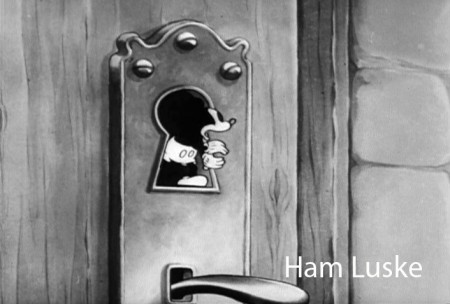

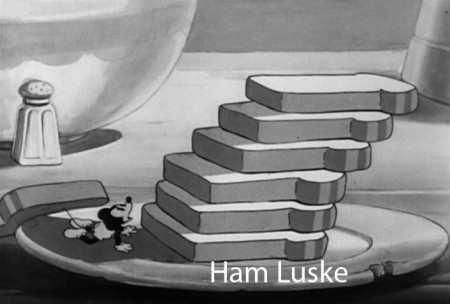

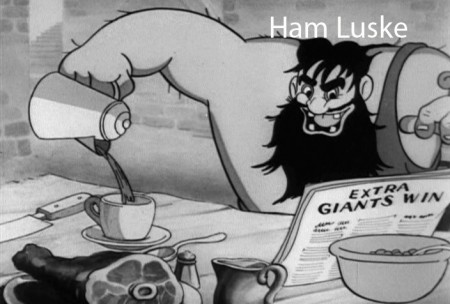

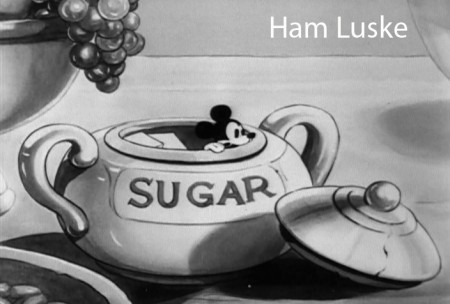

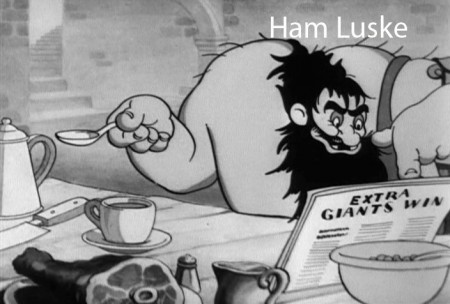

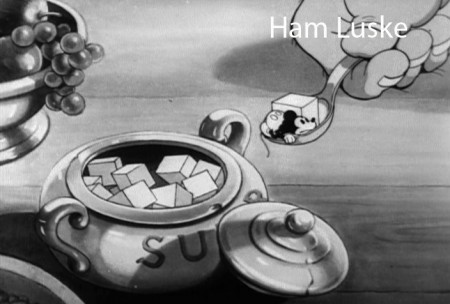

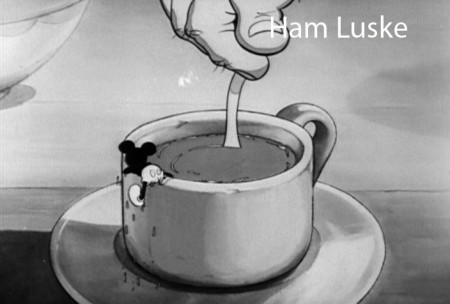

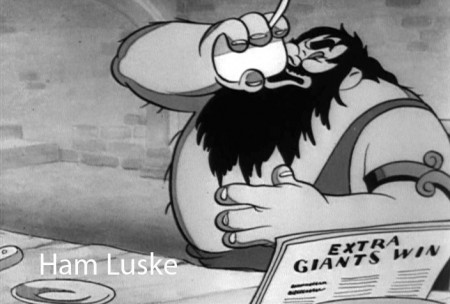

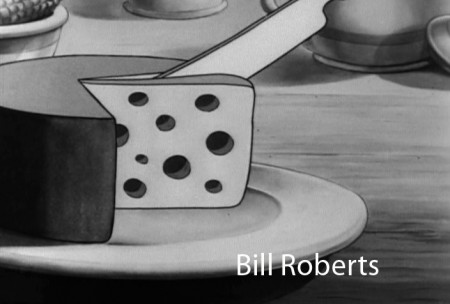

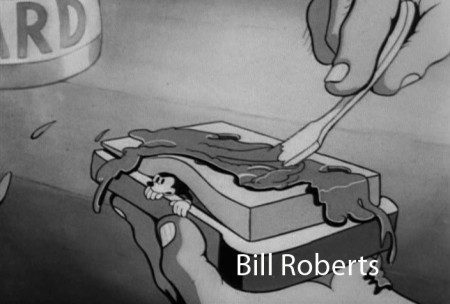

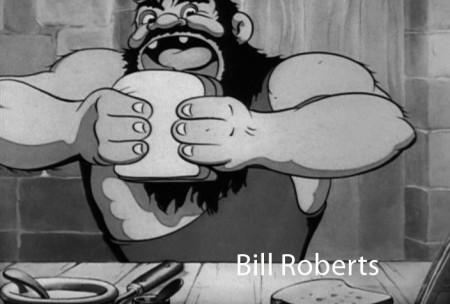

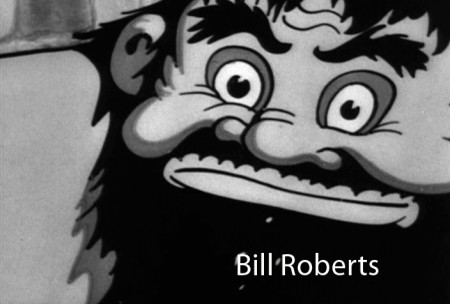

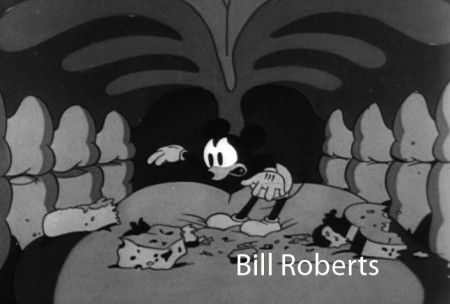

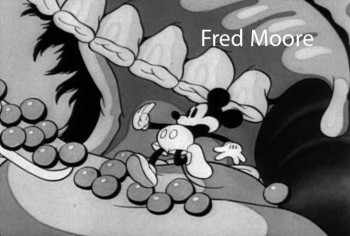

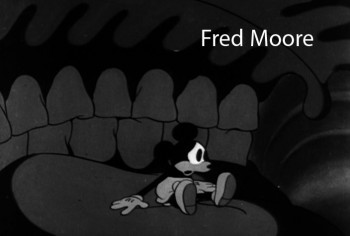

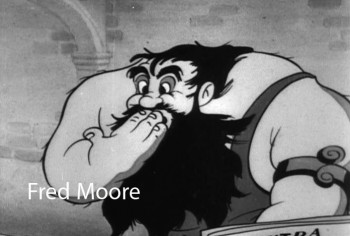

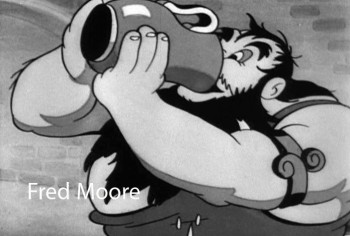

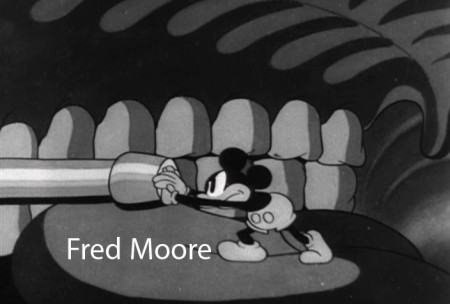

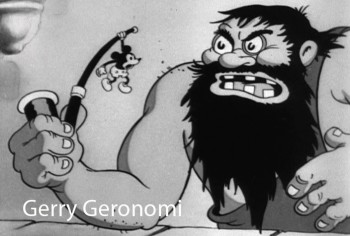

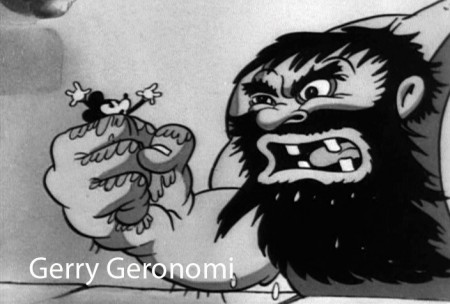

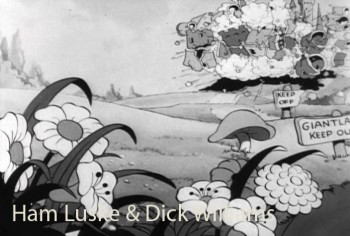

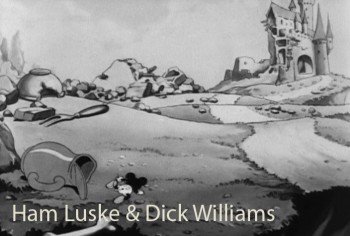

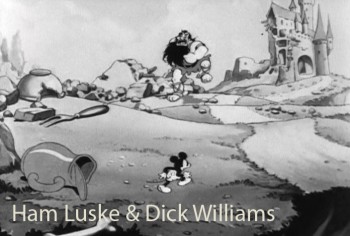

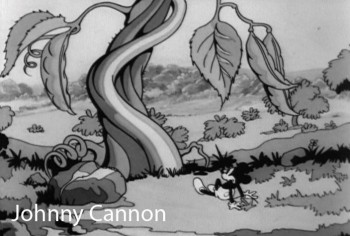

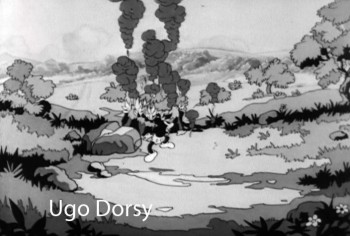

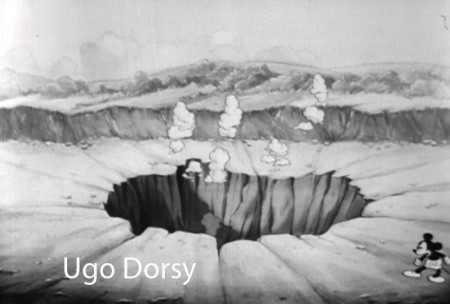

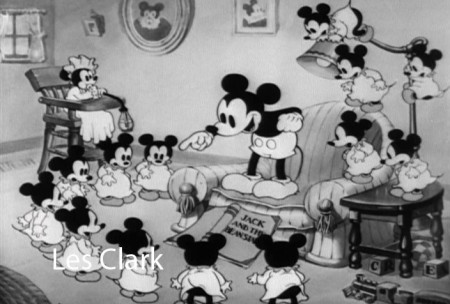

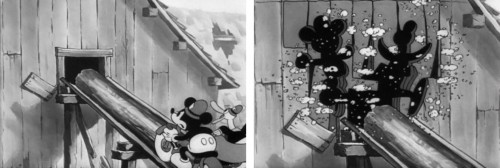

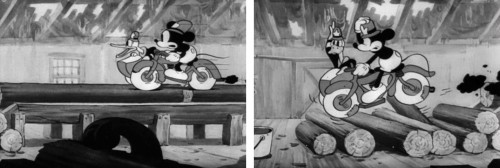

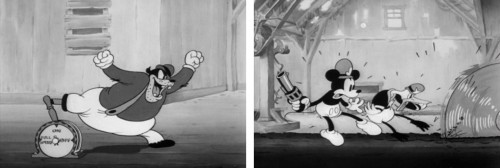

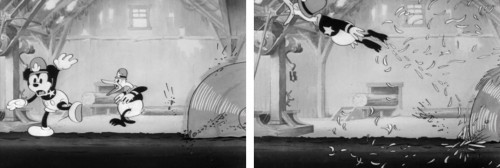

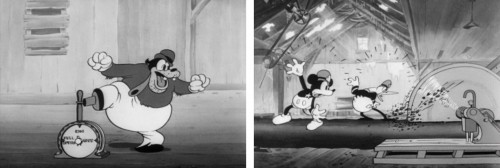

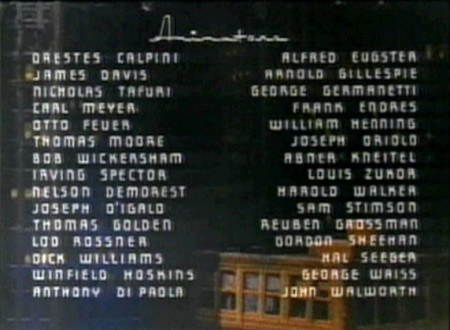

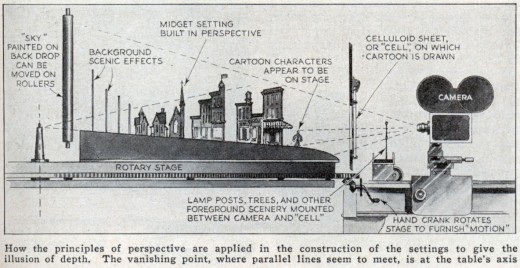

- For the past couple of weeks, Hans Perk at A Film LA has featured the animator drafts for the Disney short, Giantland. I’ve taken the opportunity to pull some frame grabs and label the animator for each particular scene. The original drafts have the film titled at “Mickey and the Giant.”

- For the past couple of weeks, Hans Perk at A Film LA has featured the animator drafts for the Disney short, Giantland. I’ve taken the opportunity to pull some frame grabs and label the animator for each particular scene. The original drafts have the film titled at “Mickey and the Giant.”

The film was directed by Burt Gillett and released on 11/25/1933.

The animation was by Les Clark, Cy Young, Johnny Cannon, Dick Huemer, Ham Luske (one scene with Dick W[illiams]), Bill Roberts, Fred Moore, Gerry Geronimi, Gilles Armand “Frenchy” de Trémaudan, Ben Sharpsteen, and Ugo D’Orsy.

Here’s the YouTube version:

_________________

The Ub Iwerks short, “Jack and the Beanstalk” is interesting in that Castle Films distributed the 8mm & 16mm home movie versions of the short duriing the 50s and 60s. This allowed the Iwerks film to be more familiar to many people today. I actually studied the film frame-by-frame dozens of times when I was a kid. I got to tell Grim Natwick that his was the first animation I ever really studied.

The film had many similarities, but the approach was very different. By this time, the Disney studio was trying to improve themselves. Cartoon fantasy such as buzzing saws, representing sleep, and the tips of shoes opening to reveal smelly toes, would not be part of the Disney approach. There was more realism, hence better acting, in the Disney shorts. Iwerks hung fast to the fantasy, just as the Fleischer films did so into the late 30s.

The Iwerks film was in color (albeit Cinecolor.)

It’s amazing how similar yet very different the Iwerks short,

Jack & the Beanstalk is. The Disney studio seems to have

gone for a more realistic approach, while the Iwerks’ team

delved more into the cartoon fantasy of the animation.

Disney &Frame Grabs 06 Sep 2011 07:04 am

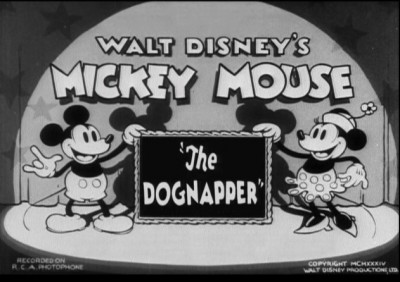

Dognapper

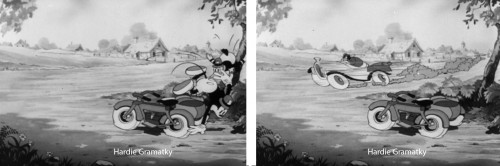

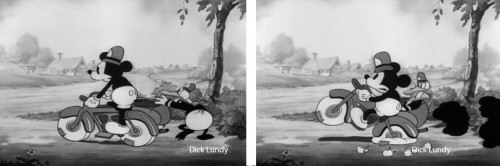

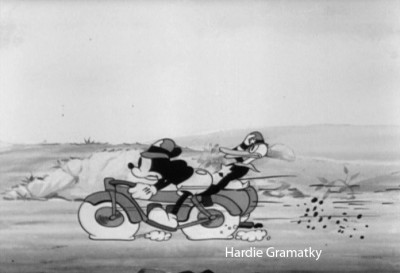

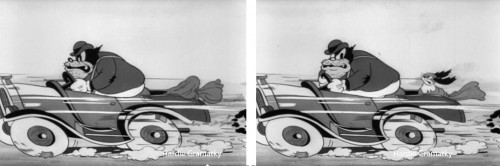

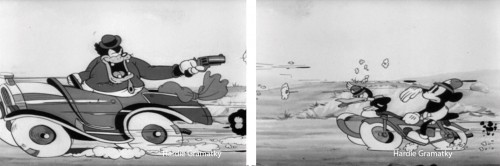

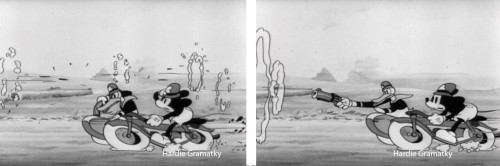

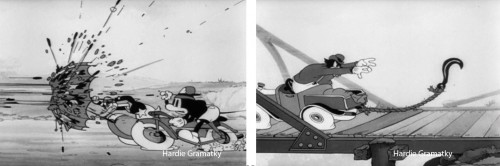

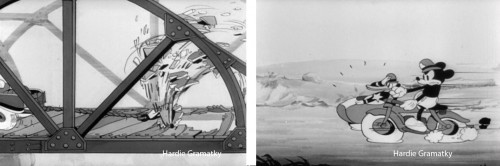

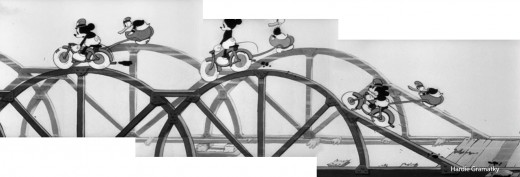

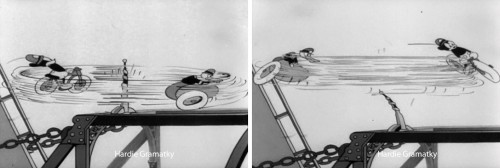

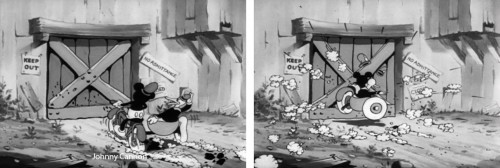

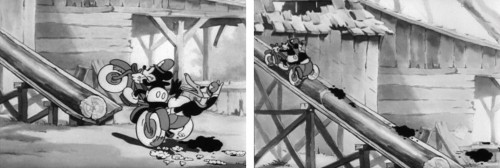

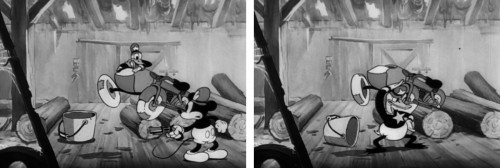

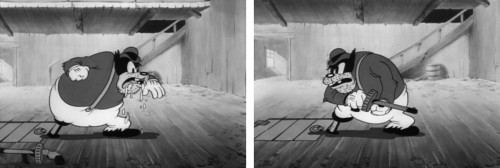

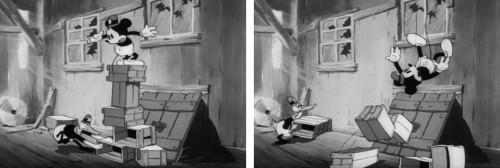

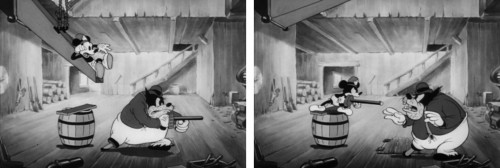

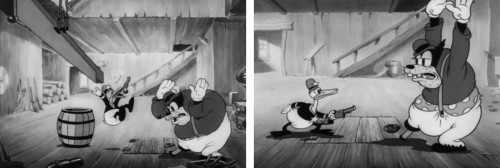

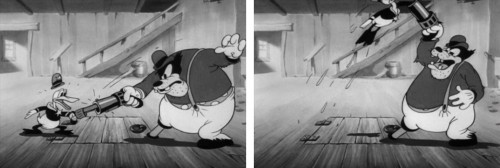

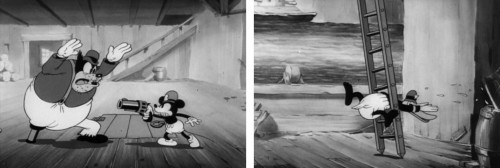

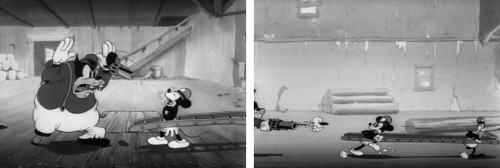

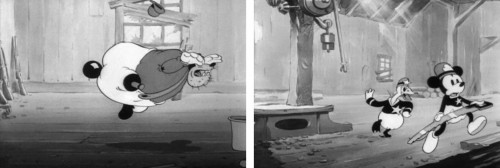

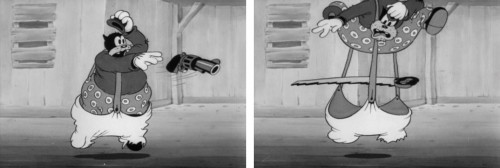

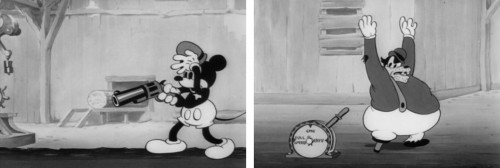

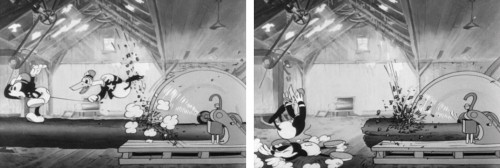

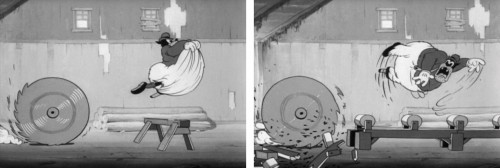

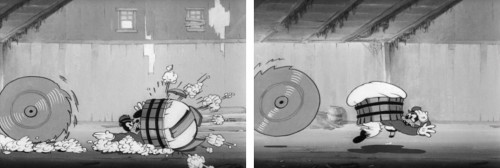

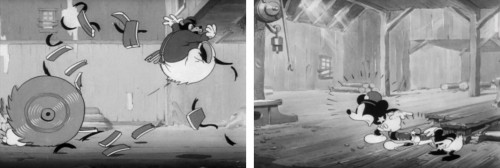

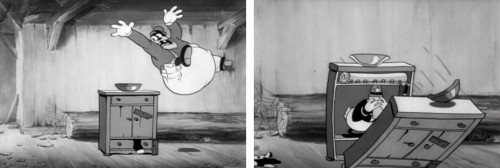

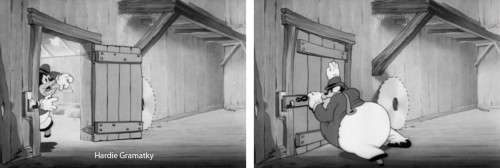

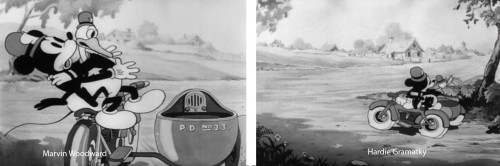

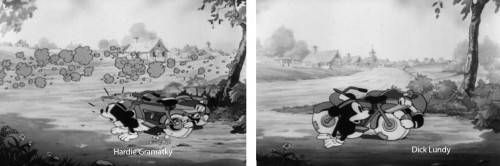

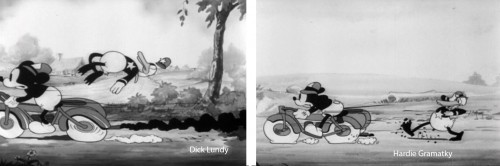

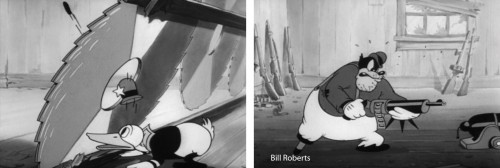

- Time to move on from the Mondays at the Multiplane Camera by putting up an enormously large number of frame grabs from this Mickey/Donald short film, The Dognapper. It’s only the third Donald Duck cartoon, (following The Wise Little Hen and Orphan’s Benefit) and already he’s co-starring with Mickey. (Although he doesn’t get billing, yet.) The short was done in 1934, and the Disney animation was just starting to get a bit more sophisticated than the rubber hose characters they’d done in the silent era. I find this a very attractive short; the Backgrounds really help. This is the Disney period that I love. I can’t get enough of the animation of Johnny Cannon and Hardie Gramatky. I’m not so keen on the non-stop action of the short, but I like the look and the imagination within the format. The film was directed by David Hand.

I’ve added animator credits to each frame. This comes from the film’s drafts as posted by Hans Perk on his site, A Film LA, a treasure of a site. (IMDB has Ham Luske and Les Clark as animators on it. I’m not sure where they got their information.)

Here are a bunch of frame grabs:

Title Card

3

3

Marvin Woodward – Hardie Gramatky

5

5

Hardie Gramatky – Dick Lundy

7

7

Dick Lundy – Hardie Gramatky

36

36

Bob Wickersham – Gerry Geronomi

47

47

Gerry Geronomi – Bill Roberts

67

67

Hardie Gramatky – Bob Wickersham

Here’s the movie.

Daily post &Frame Grabs 29 Aug 2011 06:41 am

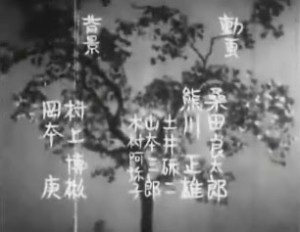

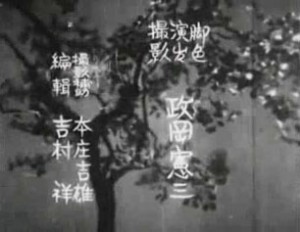

The Multiplane Camera in Masaoka’s 1943 film

- Kenzo Masaoka was an early pioneer of Japanese animation. Masaoka established Masaoka Film Production In 1932 and gained the support of the company, Shochiku; together they produced “The World for the Power and Women†in 1933, which was the first talking film in Japan. He also introduced the use of cels to Japan. He produced many other films in the thirties and was considered the “Japanese Disney”.

In 1943 he created the short Spider and the Tulip. The film tells the story of a spider who lures a ladybug to its web. The spider, in blackface, is obviously a representation of the the American force trying to invade Japan. The innocent ladybug does its all to fight back. The film incurred the wrath of the military since it wasn’t obviously about the war.

The film, has extensive use of the multiplane camera throughout. Primarily, it’s used for pans and the look of depth in many of the still setups with the BGs out of focus. I’m going to post some frame grabs culled from a streaming video copy, which I also embed at the bottom of this post, so you can watch the film. Unfortunately, the frame grabs are small. I encourage you to go to Network Awesome where I was first introduced to this and several other Japanese classics. Cory Gross did an excellent job of analyzing these films.

1

1The opening titles are against a

soft BG probably multiplane.

3

3

The flower backdrops set the mood

for the delicate film to follow.

4

4

The last title looks to be a constructed set

as the camera moves in on the tree.

5

5

The camera move feels almost hand-held.

6

6

CU of the spider against a soft background.

8

8

There’s a long pan of flowers as the fly

flies across the screen to the ladybug.

9

9

Flowers pass in multiplane levels.

17

17

The pan ends on the beautiful rose.

18

18

The ladybug stands on a leaf in the foreground, singing.

19

19

She turns as the fly enters the scene.

21

21

Cut to the spider who sings a response.

22

22

You can see that all the Bgs use the multiplane focus.

23

23

The spider moves closer to her.

24

24

There’s a two-shot with the ladybug in focus

and the spider out of focus.

25

25

Rack focus and the spider comes in sharp.

26

26

The camera moves in on the spider.

27

27

It goes in full on the spider.

29

29

Later in the film, a storm comes up.

30

30

There are many attractive shots within this sequence,

and I urge you to watch the film, embeded below, for it.

32

32

This is quite an interesting film regardless

of the year it was created in Japan and the

enormous struggles going on in that country.

.

Fleischer &Frame Grabs 08 Aug 2011 06:44 am

Fleischer Hoppity Multiplane

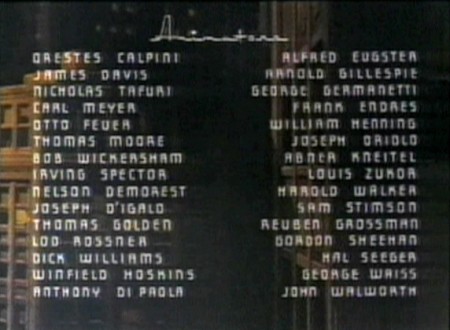

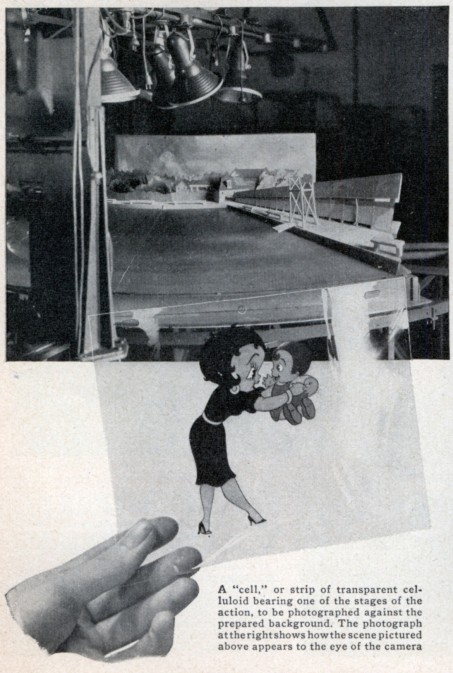

- Last week we looked at the Fleischer multiplane camera. It’s a horizontal device that shot flat animation art (cels) standing in front of 3D background constructions. Little sets that were able to add a unique look to their cartoons.

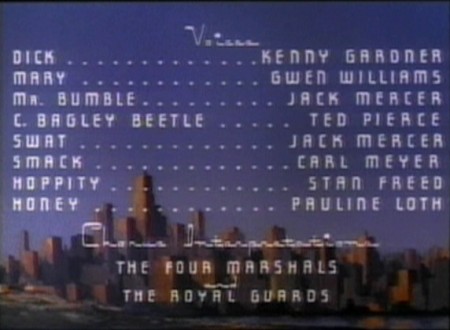

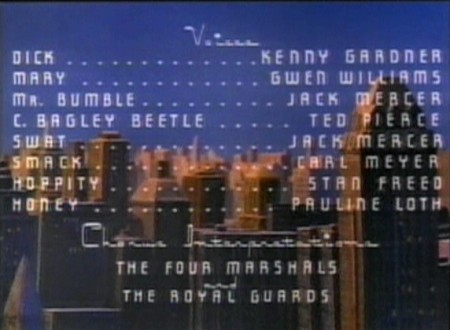

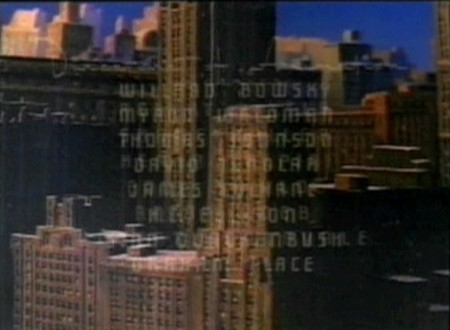

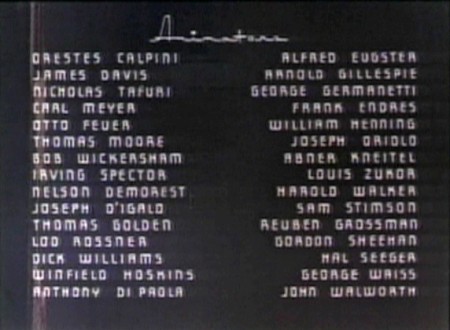

In the two Fleischer animated features, there’s only one scene that uses this multiplane camera, and that’s in the opening titles of Hoppity Goes To Town. I felt we couldn’t leave the Fleischers without a focus on that scene. So that will be the subject of today’s post.

Dave Fleischer in front of the multiplane 3D camera on Hoppity Goes to Town

Picture borrowed from: Ryan & Stephanie’s Fleischer Gallery

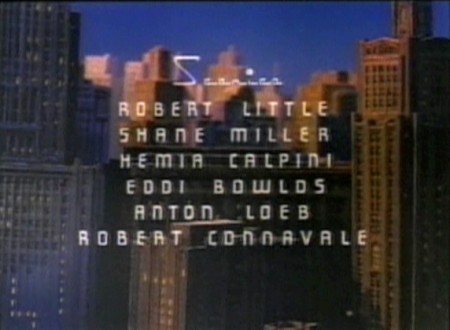

The entire multiplane pan is blocked out, in part, by the film’s credits.

I’ve taken frame grabs trying to indicate the move

while trying to accomodate the credits.

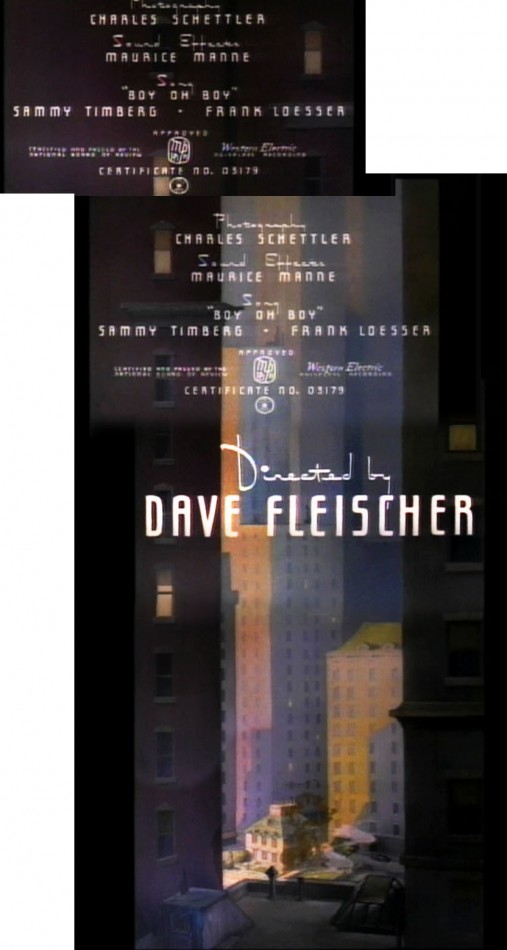

1

1

The opening starts over flat art coming from a star

in outer space, down to earth to this LS cityscape.

2

2

The multiplane scene dissolves in here . . .

3

3

. . . and pans down toward the street level as

it moves toward screen right.

5

5

That’s the Brill Building in the screen’s center

nopt far from the studio of the Fleischers.

7

7

As we go down, the color mix gets less golden . . .

8

8

. . . and sits more in shadow.

11

11

Here is a transition point.

12

12

The background darkens to accomodate the

dissolve to a flat-art pan during a credit dissolve.

The pan of the 3D setup dissolves to this flat art

which pans down to the start of the film.

There are so many good examples of the Fleischer multiplane. I just chose two in the past couple two weeks, and I hope you’ll review some that you like. There are many on YouTube.

Fleischer &Frame Grabs 01 Aug 2011 06:30 am

Fleischer’s 3D Multiplane – Little Dutch Mill

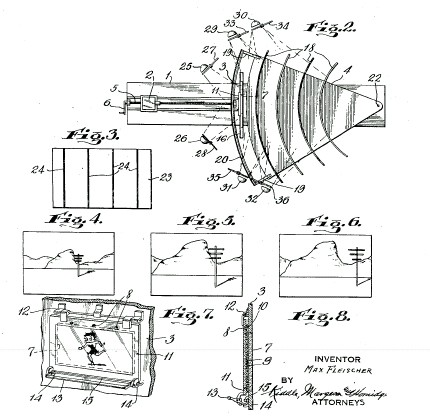

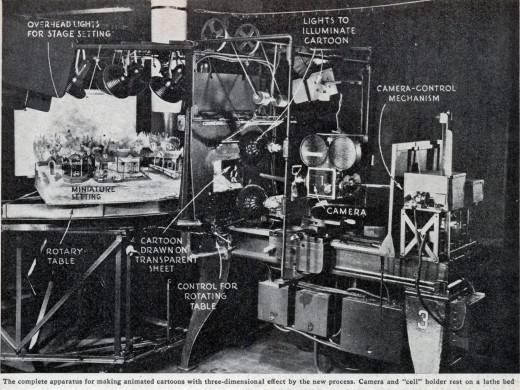

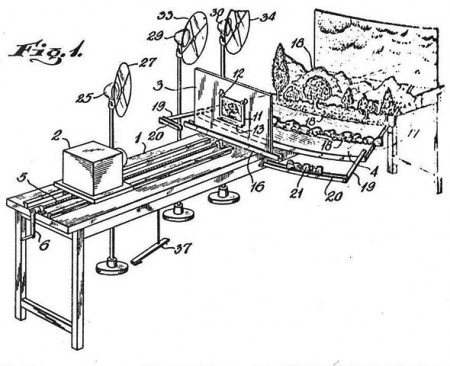

- We’ve been looking at the Disney multiplane camera, but let’s keep going back in time. The Fleischer studio had its own 3D setup, and it was very different from the Disney version. Little cartoon sets were constructed on a horizontal setup with the cels being placed in the foreground of the set. These sets could move east and west or in a circular motion. The 2D animated cels stood in front of the moving set and it gave the effect of a 3D world behind them. The end result was to show the 2D cels moving in front of a 3D set.

Here are some stills and artwork showing how the contraption worked.

Images from the patent application for the Fleischer 3D multiplane camera.

Images above from Modern Mechanix/November 1936

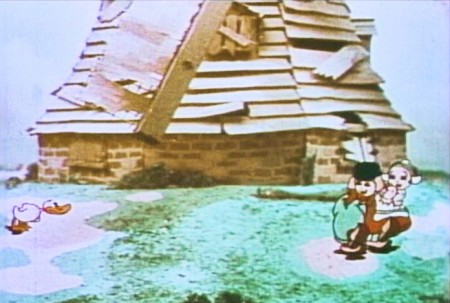

One of my favorite cartoons that really showed off this process, was a color cartoon called, The Little Dutch Mill. There was a lot of rotation of the characters running and skipping around the mill, which, of course, had the blades turning. It felt like the rotation was 360°, but that certainly couldn’t have been the case. But it was well planned to make it feel as though that were happening. Here are some grabs of scenes that employed the specialised camera.

1

1Disney still had the rights to Technicolor, so the

Fleiscers used the 2-strip Cinecolor – orange & green.

3

3

Here’s the first scene done as flat art.

5

5

. . . which revolves as the kids enter the scene.

6

6

The closer shot of the kids looks flat, especially with that animated windmill blade.

7

7

The mill isn’t revolving here.

8

8

But the camera zip pans across to some 3D scenics.

9

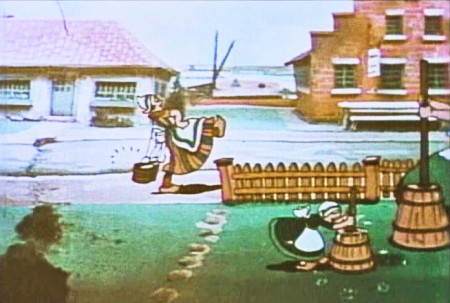

9

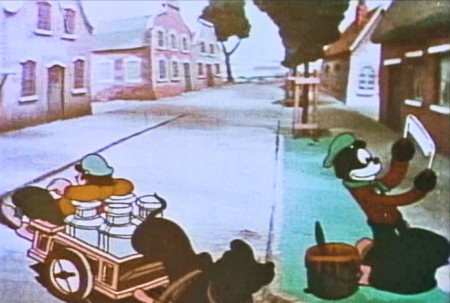

We follow a woman carrying water as she walks . . .

10

10

. . . into town. 3D movement on the BG.

11

11

The woman, the picket fence level, and the

churning family have to match the BG movement.

12

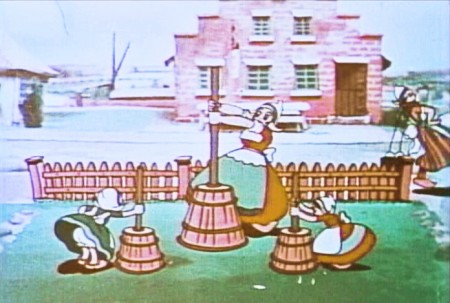

12

We stop on some kids & a woman churning butter.

13

13

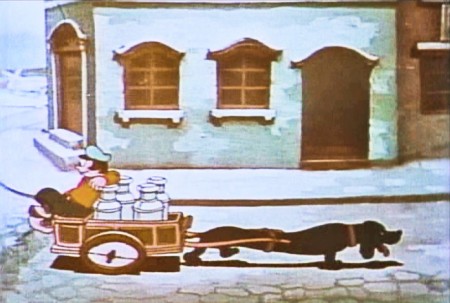

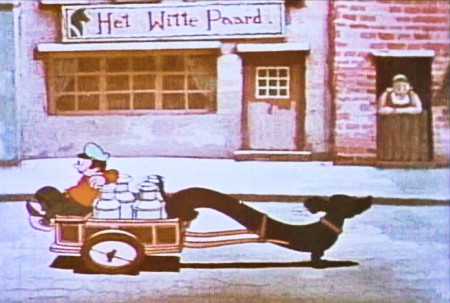

A dachsund leads a cart with a lazy guy.

14

14

The town moves in 3D perspective.

15

15

The dog & cart cycle is repetitive.

16

16

The cart turns toward the camera leading us toward . . .

17

17

. . . a shoeshine boy carving away at the wooden shoe.

19

19

. . . to countryside that we seem to have seen before.

22

22

. . . the old miser/villain of the short.

23

23

He rattles his nasty complaint.

24

24

He steps on three tulip plants.

25

25

He stops to beg a coin from a fat guy with a pipe.

26

26

Another Zip pan to screen left.

27

27

Back to the revolving mill. The kids are dancing with their duck.

There are a lot of other scenes that reuse the master BGs of the mill.

There’s only one other scene I want to feature which isn’t repeated frequently. Within the miser’s home, the town saves the day by cleaning things up. We get a pan across the place once the town has wiped everything down.

1

1We get a simple pan across the mill interior.

2

2

The pan shows off the 3D camera well. Everything is modeled and well constructed.

3

3

There’s no animation in the scene, so the BG looks great.

4

4

Most of the other interior shots of the mill are flat art,

so this scene is a stand-out.

Basically, other than a sweet story creatively told, there’s little more than the wonderful scenery moving. Oftentimes there’s not even animation or there are animated cycles moving in front of the panning BGs. The one regret is that the film hadn’t been done in

3-strip Technicolor.

Disney &Frame Grabs &Layout & Design &Models 25 Jul 2011 06:53 am

The Old Mill Multiplane

- Having visited the multiplane camera scenes of SNOW WHITE, I can only see the usefulness of going to the keystone of the camera, “The Old Mill.” It’s on this lyrical and beautifully produced short that they admittedly devised the idea of testing the multiplane camera in action. However, in an interview I’ve read with director, Wilfred Jackson, we find that the camera wasn’t available for much of this film. It was being tied up with a number of shots from

- Having visited the multiplane camera scenes of SNOW WHITE, I can only see the usefulness of going to the keystone of the camera, “The Old Mill.” It’s on this lyrical and beautifully produced short that they admittedly devised the idea of testing the multiplane camera in action. However, in an interview I’ve read with director, Wilfred Jackson, we find that the camera wasn’t available for much of this film. It was being tied up with a number of shots from  SNOW WHITE. The interview is by David Johnson posted on American Artist‘s site. Here’s the passage I’d read:

SNOW WHITE. The interview is by David Johnson posted on American Artist‘s site. Here’s the passage I’d read:

- DJ: Since you worked on The Old Mill, you were involved with the multiplane camera. Can you tell me about Garity [the co-inventor] and the invention of this thing and some of the problems and miracles that it did.

WJ: What I can tell you about my experiences with it was the The Old Mill was supposed to be a test of the mutiplane, to see if it worked. Somehow, we were so held up in working on The Old Mill by assignments of animators because Snow White was in work at that time and animators that I should have had were pulled away just before I got to them and other animators were substituted because Snow White got preference on everything. And we got our scenes planned and worked out for the multiplane effects and by that time some of the sequences on Snow White were being photographed. The multiplane camera itself had all kinds of bugs in it that had to be worked out. We were held up until so late that I actually did work on another short – I don’t remember which short. I don’t even remember if I finished it up – did work on some other picture to keep myself busy while we could get facilities to go ahead on The Old Mill. By the time they had got the bugs out of the multiplane camera, they had multiplane scenes for Snow White to shoot and they got it busy on those first. Finally in order to get The Old Mill out the scenes that had been planned for multiplane had to be converted to the flat camera to do the best they could. You won’t find more than a very few multiplane scenes in The Old Mill.

DJ: I wasn’t aware of that.

WJ: I’ve had messed up schedules on pictures but I’ve never had a more messed up one than I can remember for The Old Mill.

So, of course, I’ve searched for scenes that I believe are definitely part of the shoot done on Garity’s vertical Multiplane Camera.

The film is little more than a tone poem of an animated short. It’s about as abstract a film as you’d find coming out the Disney studio in the 30s.

Let’s take a look at some frame grabs from the film, itself:

1

1We open on a slightly-out-of-focus mill with a spider’s web

filling the screen, glistening in focus, in the foreground.

2

2

The camera moves in on the mill and the

spider’s web goes out of focus and fades off.

3

3

Dissolve through to a closer shot as we move in.

4

4

Dissolve through to an even closer shot.

5

5

Foreground objects go out of focus as we move in on the mill.

7

7

Cut to a bird flying in the foreground carrying a worm.

8

8

The interior of the mill, viewed through the window, is dark grey.

9

9

Dissolve into the next shot which looks as though it appears in the framed window.

Here, we cut to a long pan up the mill using the multiplane. The lighting in this scene is inconsistent. There are flares and glares and some minor jerks to the artwork. No doubt this was done on the multiplane camera, and it would have been reshot if there were time and money.

I couldn’t hook up the artwork to simulate the pan since overlays from one frame didn’t match the next. It was all moving with multiple levels (maybe five?) and they didn’t match from one frame to the next.

1

1The shot starts from the top of the mill looking down on the birds.

2

2

It starts moving up the central column.

6

6

Stopping on a pair of lovebirds.

7

7

The camera continues upward.

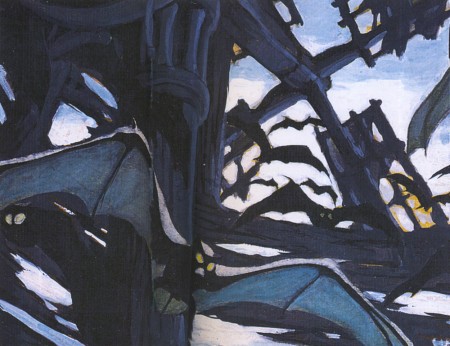

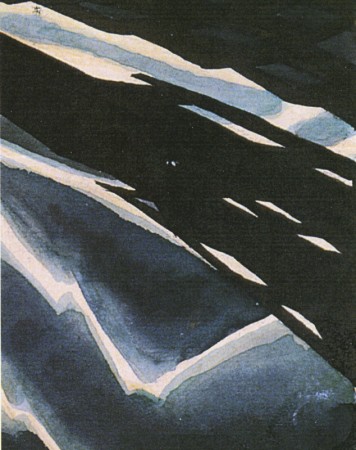

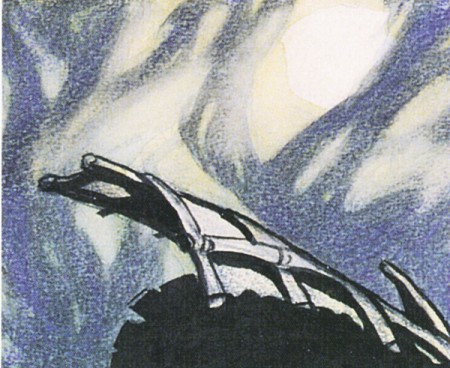

At this point there is a cut outside to bats fleeing the Old Mill for the night.

Gustaf Tenggren made some preproduction drawings of this scene which can be found in John Canemaker‘s book, Before the Animation Begins which in itself is something of a tone poem of a book devoted to many of the designers at the Disney studio.

1

1

Now here are frame grabs from the film, itself.

1

1

4

4

The multiplane camera is used only for the exterior shots of the mill

shown over the course of a number of scenes.

5

5

Placed as I’ve done with them, they look as though

they’re one continuous scene over the length of the storm.

21

21

Finally, things settle down and the camera comes to

the Old Mill at rest in the morning.