Category ArchiveDisney

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Disney &repeated posts 17 Aug 2011 06:38 am

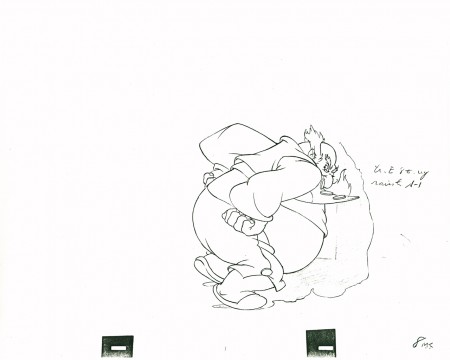

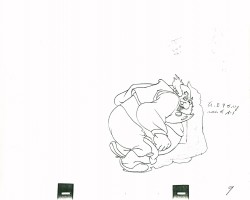

Dumbo’s Bath – recap

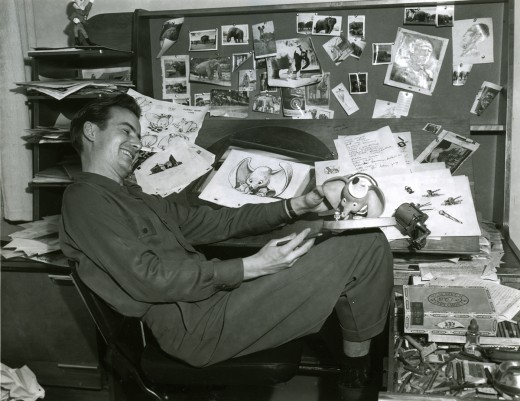

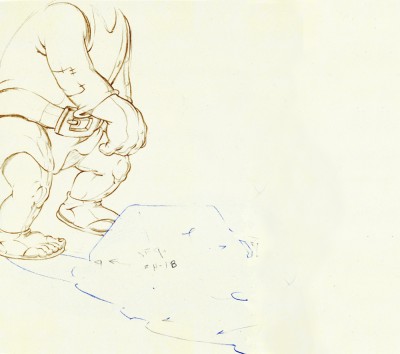

Continuing the celebration of Bill Tytla’s magnificent artrwork, I’m reposting this piece on Dumbo’s bath.

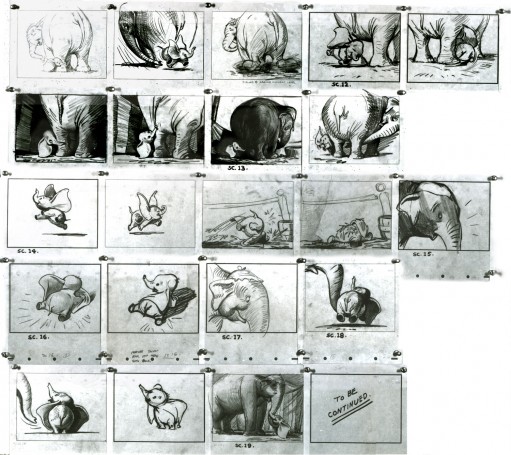

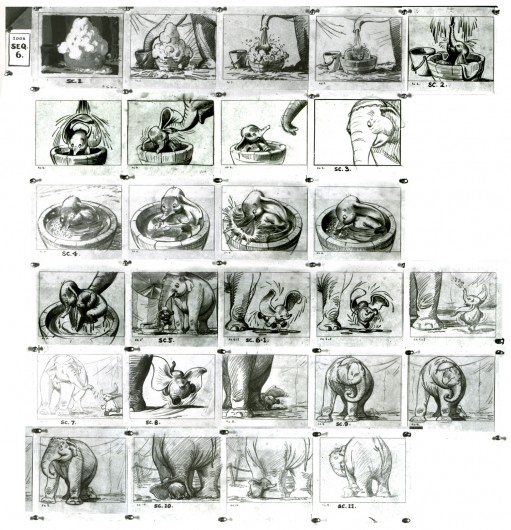

- Thanks to a loan from John Canemaker, I can continue posting some of the brilliant storyboard work of Bill Peet. The guy was a masterful artist. Every panel gives so much inspiration and information to the animators, directors and artists who’ll follow up on his work.

- Thanks to a loan from John Canemaker, I can continue posting some of the brilliant storyboard work of Bill Peet. The guy was a masterful artist. Every panel gives so much inspiration and information to the animators, directors and artists who’ll follow up on his work.

This is the sequence from Dumbo wherein baby Dumbo plays around the feet of his mother. Brilliantly animated by Bill Tytla, this sequence is one of the greatest ever animated. No rotoscoping, no MoCap. Just brilliant artists collaborating with perfect timing, perfect structure, perfect everything. Tytla said he watched his young son at home to learn how to animate Dumbo. Bill Peet told Mike Barrier that he was a big fan of circuses, so he was delighted to be working on this piece. Both used their excitement and enthusiasm to bring something brilliant to the screen, and it stands as a masterpiece of the medium.

Of this sequence and Tytla’s animation, Mike Barrier says in Hollywood Cartoons, “What might otherwise be mere cuteness acquires poignance because it is always shaded by a parent’s knowledge of pain and risk. If Dumbo “acted” more, he would almost certainly be a less successful character—’cuter,’ probably, in the cookie-cutter manner of so many other animated characters, but far more superficial.”

I had to take the one very long photstat and reconfigure it in photoshop so that you could enlarge these frames to see them well. I tried to keep the feel of these drawings pinned to that board in tact.

(Click any image to enlarge.)

Here are frame grabs from the very same sequence of the film showing how closely the cuts were followed. Even in stills the sequence is stunning.

(Click any image to enlarge.)

.

.This film is a gem.

The dvd also has one of my favorite commentary tracks throughout.

John Canemaker, by himself, talking about the film. It’s great!

From Hans Perk’s A Film LA:

Seq. 06.0 “Menagerie – Mrs. Jumbo Goes Berserk”

Directed by Wilfred Jackson, assistant director Jacques [Roberts?], layout Terrell Stapp.

Dumbo being washed by Mrs. Jumbo, animated by Bill Tytla, with effects by Art Palmer, Cornett Wood and Sandy Strother.

Animation Artifacts &Books &Commentary &Disney 11 Aug 2011 06:52 am

Response

- On Tuesday, I’d posted a review of Timothy Susanin‘s excellent book, Walt Before Mickey: Disney’s Early Years 1919-1928. I loved the book and, in fact, worried that I was being too critical. I did tend to go on quite a bit about the details on details within the book.

To my surprise I’d received an email response from Mr. Susanin, and I asked him if he would mind my posting his letter. He immediately gave me permission and here’s his response to my review:

Dear Mr. Sporn,

Dear Mr. Sporn,

Many thanks for reading my book; for writing a review; and for your kind words.

I can’t tell you how much fun I had learning the story of Walt’s first decade. It was a most enjoyable and unexpected hobby, and I am sorry it’s over!

I am biased about Walt, of course, so I found the subject matter thrilling and a page turner, like you.

Your review is dead on in a number of respects. I am a Disney fan, not an animation expert, thus I was not equipped to search for the art, as were J.B. and Russell. Being a lawyer who has done many investigations, and written many detailed factual reports based on investigations, I was simply all about finding out what happened during Walt’s “missing decade.”

There was a reference in the Laugh-O-gram bankruptcy file to a studio “minute book,” and I would have been thrilled had a daily diary of any or all of that decade still existed! For me, following Walt day by day was the way to learn the real Walt and to see how he really got started.

So for me, a novice author and biographer — and maybe this notion would not be acceptable to other, experienced authors and biographers — there was real worth in learning all of the detail you mention in your review. Because no daily account existed, trying to find out at least what he was doing on a monthly basis helped bring this period alive for me.

The overload of detail — again, for me — allowed the physical spaces he occupied, the friends and colleagues, the look and feel of the period, the films produced to all come together and create a real portrait of that missing decade.

I agree that the question is: is this a viable biography for others outside this “niche market?” I didn’t set out to write a book, and once a book resulted, it was the book I would have wanted, because of the level of detail I wanted to know in order to really learn that period of Walt’s life. So, it worked for me!

And, as you point out, there were limitations. I had no budget. I had no publisher until the book was finished. I was not sure until near the end of the process that the Disney Company would provide photos.

So….this was very much a project where I was limited to take what others had done

and try to build on it, add facts to it, string things together, on my own and in my

spare time —- evenings and weekend.

I pulled all this together to learn about Walt in the 1920s. The info turned into a timeline that turned into a more detailed chronology that turned into a book. Along the way, I tried to find answers to whatever questions I had so that the blanks could be filled in.

I think what resulted is a work that I would have loved to come across in a book store or in a library, along with the realization that others would feel the same way, but maybe not a lot of others!

In the end, I got a real sense of who Walt was; what the first ten years of his career were like; how they set the stage for the rest of his career; and how a lot of his original collaborators fit into the big picture. It really sets the table nicely for me to now go on and read and learn about Walt in the 30s, 40s, etc.

In the end, I got a real sense of who Walt was; what the first ten years of his career were like; how they set the stage for the rest of his career; and how a lot of his original collaborators fit into the big picture. It really sets the table nicely for me to now go on and read and learn about Walt in the 30s, 40s, etc.

Unlike you, I did not want the book to go on. After six years and many rewrites and endless proofreading, I wanted it out the door and almost got sick of it! Maybe you can predict what happened after that: I now find myself wondering with increasing frequency about the spring of 1928, and what happened —- in a detailed way, on a daily or monthly basis! —- as Mickey appeared on the scene.

I thought that I would have nothing further to contribute to the Disney canon because, from Mickey’s appearance in 1928 til today, enormous amounts have been written about Walt’s story. Unlike the “missing decade” of the 1920s, the record is complete as far as the other decades of Walt career are concerned.

And yet….I find myself getting the urge to dig into the spring of 1928 and see where that takes me.

I don’t really know if I have another book in me, but my mind is starting to wander in that direction. I’ll keep you posted!

Many thanks again for your interest and your review.

Boy, do I hope he comes up with something about those several months between the start of Plane Crazy and the premiere of Steamboat Willie. Can you imagine the pressure on Walt and Roy? They’d just been robbed of their staff and had lost a semi-lucrative job doing Oswald cartoons. They create a mouse character, and no one wants the first short. So they do a second film starring Mickey, and still they can’t sell it. They do a third one trying to capitalize on the incoming sound transition. They show the film at one theater – for free – just to get it in front of an audience. Success! That short period is a tale in its own, and it’s never really been covered by writers.

In the photo, above: LtoR – Irene Hamilton (Inker), Rudy Ising, Dorothy Manson (Inker), Ubbe Iwerks, Rollin Hamilton, Thurston Harper, Walker Harman (Inker), Hugh Harman, Roy Disney. Walt took the photo.

On to something else that’s related. Mark Sonntag on his extraordinary blog, Tagtoonz, has posted some rarely seen photos of the first days of Disney’s filming in Kansas City. After posting the one photo of Walt directing and Red Lyon filming the Cowles children in 1922, he was contacted by a member of the Cowles family, and they offered additional photos. Take a look.

Action Analysis &Animation &Books &Disney &repeated posts 10 Aug 2011 07:07 am

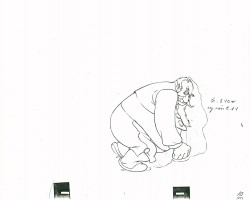

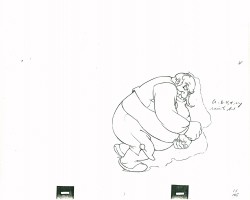

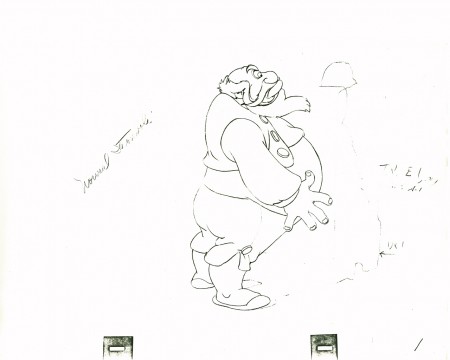

Tytla’s Willie – recap

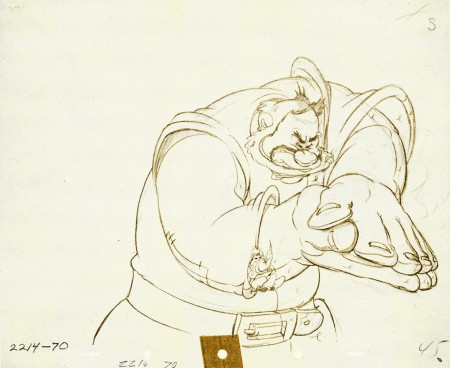

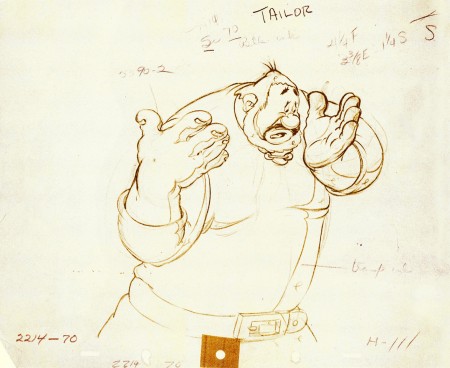

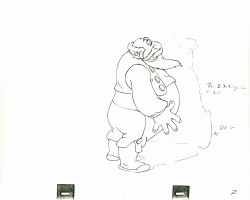

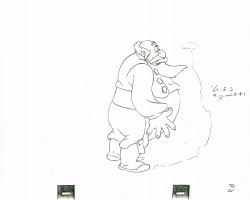

Continuing with my recap of all things Tytla, here’s a post I did on Tytla’s work on The Brave Little Tailor.

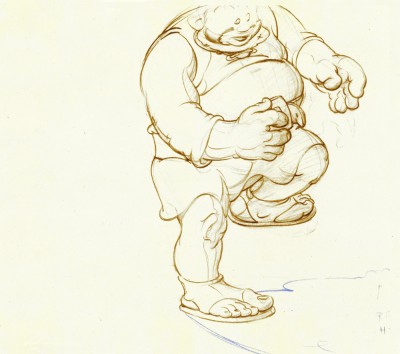

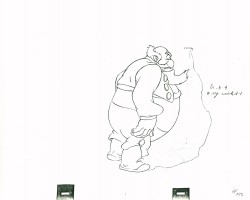

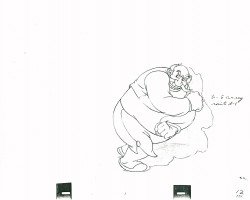

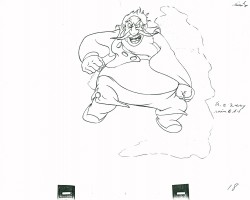

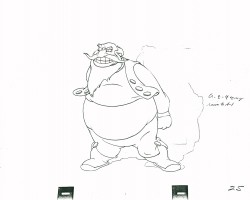

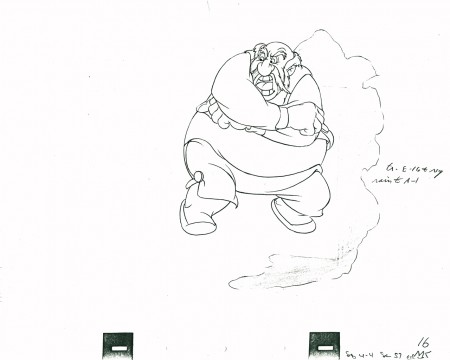

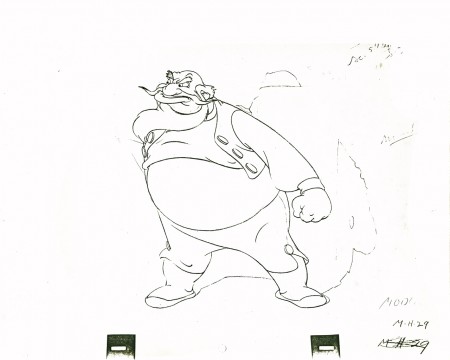

- When I was a kid, I was never a big fan of the “Willie” character, the giant in Mickey & the Beanstalk. It seemed that every fourth or fifth Disneyland tv show would have this character in it (or else Donald and Chip & Dale). As I got older and grew a more educated eye for animation, I came to realize how well the character was drawn and animated.

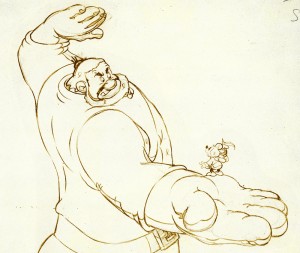

Willie first appeared in the classic Mickey short, The Brave Little Tailor, and he appeared fully formed. Bill Tytla was the animator, and he appeared to have fun doing it.

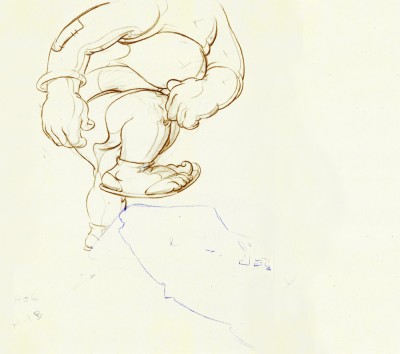

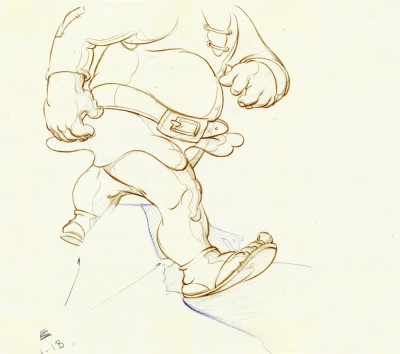

In John Canemaker‘s excellent book, Treasury of Disney Animation Art, there are some beautiful drawings worth looking at. Here they are:

1

1(Click any image to enlarge.)

So let’s take a closer look at some of these drawings.

.

Drawing #3 features this weight shift. As the right foot hits the ground it pronates – twists ever so slightly inward. The hands do just the opposite. The left hand reaches in while the right hand holds back, completely at rest.

It’s a great drawing.

.

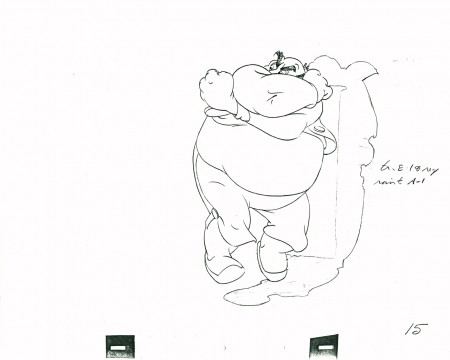

.

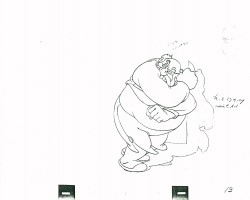

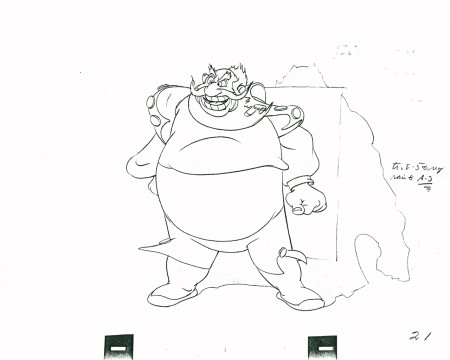

.

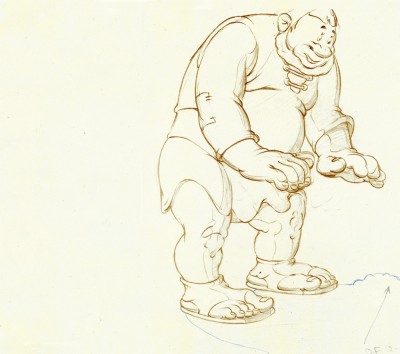

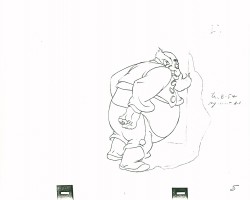

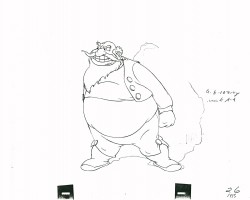

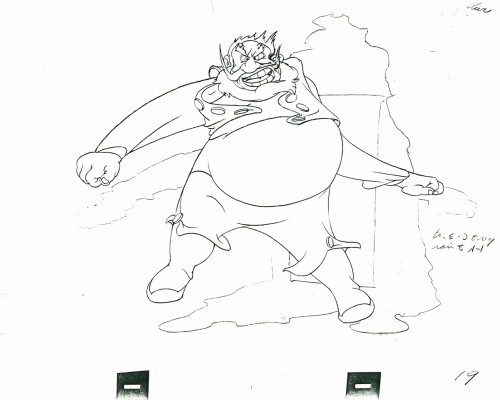

Drawing #4 shows Willie landing on that right foot, and his entire body tilts to the right. The hands twist completely to the left trying to maintain balance. The left foot up in the air is also twisting to the left before it lands twisting to the right.

.

.

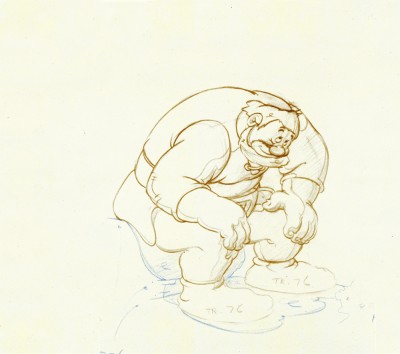

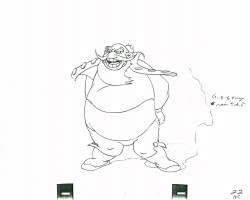

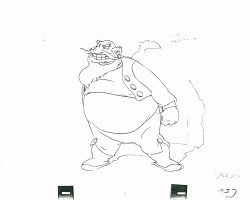

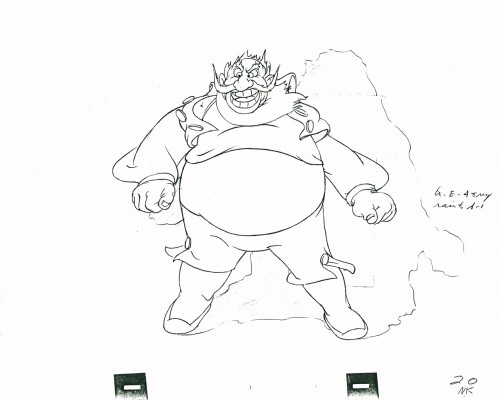

I love how drawing #5 features the two hands flattened out to

make his final stand before sitting down. It’s all about gaining balance.

.

.

.

.

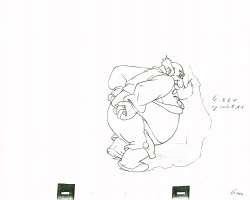

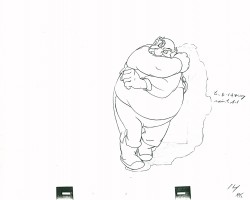

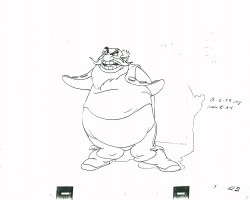

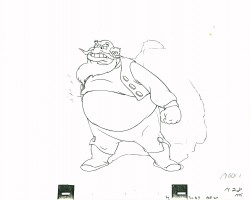

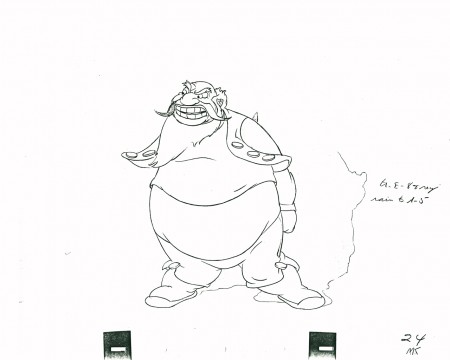

Just take a look at this beautiful head in drawing #6. He’s seated, his head has come forward and tilted forward. The distortion is so beautiful it almost doesn’t look distorted.

What a fabulous artist! This guy just did this naturally.

.

.

.

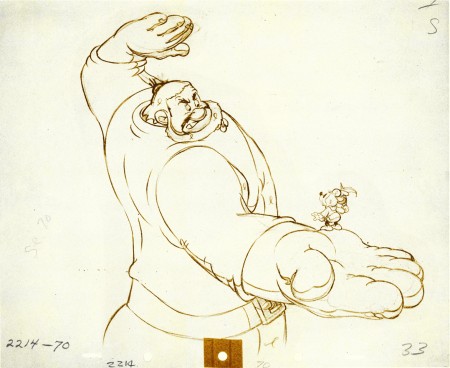

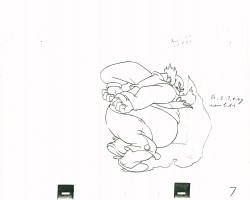

This scene begins with the seated giant eyeing the tiny Mickey Mouse in his hand. The characters are drawn beautifully almost at a rest waiting to get into the scene. The intensity of Willie’s glare is strong, and it’s obvous Mickey is in trouble.

.

Here’s the drawing of the sequence.

Here’s the drawing of the sequence.

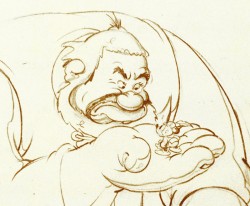

The major problem with drawing a giant is his proportion to all the other characters. The screen is more oblong and horizontalal than it is square. (Fortunately, when this film was done it was closer to a square but still not one.) Throughout the film, Tytla had to deal with a BIG Giant and little Mickey. The landscape is also small.

An obvious way of handling it – and one that would be done today, no doubt – would be to force perspective showing it from the ground up – most of the time. In the 30′s and 40′s they stuck to the traditional rule of film and editing, and they would NOT have done this.

Tytla plays with scale as the giant steps over a house and ultimately sits on it.

In this drawing, he does a brilliant drawing forcing the perspective with Mickey in the foreground and Willie’s left hand in the distance. The giant draws into this forceful perspective without calling attention to itself. Today it would be more exaggerated, but Tytla doesn’t want it to be noticed – just felt.

A real bit of art!

Here, Willie moves through that perspective of the last extreme, and he gets larger as he slams his hands to flatten Mickey. To exaggerate that flattening, Willie’s hands flatten for this key drawing. His head flattens as well in grimace.

The giant’s head will move in toward the hands to see the results, and the audience has a front row seat seeing Mickey escape up the giant’s sleeve. There’s a lot going on in this drawing.

.

.

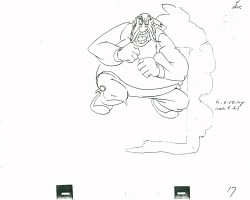

Finally, Willie tries to figure out what’s happened.

The drawing loses most of its distortion and comes to rest.

(Note that there’s still perspective distancing between the two hands.)

Mark Mayerson has done a mosaic breakdown of this cartoon and adds his excellent commentary.

Hans Perk on his site, A Film LA, has just posted the drafts to the earlier Disney short, Giantland. The draft for The Brave Little Tailor was posted a while back on this great site.

Books &Disney 09 Aug 2011 06:44 am

Walt Before Mickey – a book report

- Before I write about the book, let me say that I am truly sad to hear of the death of Corny Cole, one of those great people you meet in the world of animation who seriously changes things for you. I thank Richard Williams for introducing me to him. I’ll try to post a number of his drawings later this week.

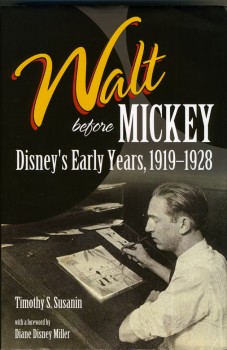

- I’ve spent a lot of time in the past two weeks reading a thoroughly enjoyable and inspiring animation book, and I wholeheartedly recommend it to anyone interested in Walt Disney or animation. Walt Before Mickey: Disney’s Early Years 1919-1928 is by Timothy Susanin, and it’s such a real treat that I had a hard time putting down. Yet I wanted to keep it alive, so I brought a bunch of other books in for the ride. I took my time reading it even though taking my time was hard to do.

- I’ve spent a lot of time in the past two weeks reading a thoroughly enjoyable and inspiring animation book, and I wholeheartedly recommend it to anyone interested in Walt Disney or animation. Walt Before Mickey: Disney’s Early Years 1919-1928 is by Timothy Susanin, and it’s such a real treat that I had a hard time putting down. Yet I wanted to keep it alive, so I brought a bunch of other books in for the ride. I took my time reading it even though taking my time was hard to do.

The book tells in elaborate detail (and I do mean elaborate) all of the steps that Disney had taken to get started in this business. The boy who learned how animation could become much more than it was and fought with all the “jack” he had to put it all on the screen. He and Roy, partners in those early days, staked everything on their belief in what they were doing. It’s a great story and makes for something of a page turner.

In J.B. Kaufman and Russell Merritt‘s book, they open with an evaluation of the early period of Disney animation: ” . . . the first striking fact about Disney’s 1920′s films is that they take no particular direction: they don’t evolve, they accumulate.” How accurate an assessment of these films. They don’t get better, they get worse almost as though Disney soon tired of doing them. The gags become repetitive; the characters lose all sense of characterization; even the live-action “Alice” goes from having a large part in the films to flailing her arms so that we can cut back to the drawn animation. This is not the Disney we know from the Thirties & Forties – the one who pushed his people to create the Art form. Essentially, Kaufman and Merritt are looking for the “Art” and give a sharp report on their findings.

This isn’t true of Susanin. His book searches only for the facts and records. But then, let’s look at how the two books were constructed. Susanin’s interviews were limited in comparison to someone like Mike Barrier who did several hundred interviews to write Hollywood Cartoons. He helped Mr. Susanin with many an interview; he also got some help from Kaufman and numerous others in gathering the details and data for the book. Mr. Susanin said, “. . .the Library of Congress, the New York Public Library, MOMA, and the like. I visited the studio when work took me to Burbank, and the Walt Disney Family Museum construction site when work took me to San Francisco. Otherwise, it was lots of virtual work and lots of phone calls with librarians around the country! ”

A lot of the source information came from authors who’d done their own books. Susanin gathered the material – and gathered A LOT OF MATERIAL.

A lot of the source information came from authors who’d done their own books. Susanin gathered the material – and gathered A LOT OF MATERIAL.

The accumulation of the facts is collected in an almost overwhelming fashion by Susanin. Every sentence in the book seems to have some source information backing it up. An almost minute-to-minute account of these early days is gathered and written about. Prior to this book, I found myself guessing at some of the material. I hadn’t really seen all the details until I had them laid out in this book. Add to that details upon details, and you’re breathless from the material presented. (Every person Disney meets seems to have their history displayed. And just read about the Laugh-O-Grams bankruptcy suit in the epilogue.)

Make no mistake about it, this is a period I am wholly and completely intrigued with. I’ve read every book and interview about it that I could find. Kaufman & Merritt’s Walt In Wonderland, Mike Barrier’s The Animated Man, Donald Crafton’s Before Mickey, even Canemaker’s Winsor McCay. I’ve read and read and read again through the material. Yet the way it’s ultimately presnted in this book is so involving. Perhaps it’s all those details I love reading.

In the three week period Walt and Lillian spent in New York looking to sign a second contract to produce the Oswald animation for Universal, you see all the meetings he has taken. All the visits to Universal and Charlie Mintz (who actually contracts the job to Disney and ultimately steals a large part of his staff so that he can dump Disney) and to MGM (Fred Quimby – of all people) and Fox. He spends a lot of time with Jack Alicote the editor of Film Daily who counsels Walt on the business side of the business. You see all the connections; you understand the seriousness of Walt’s situation and you ride with him trying to grasp what straws he has left. It’s hypnotic in all its detail, and it serves as a tight climax in a well written book.

In the three week period Walt and Lillian spent in New York looking to sign a second contract to produce the Oswald animation for Universal, you see all the meetings he has taken. All the visits to Universal and Charlie Mintz (who actually contracts the job to Disney and ultimately steals a large part of his staff so that he can dump Disney) and to MGM (Fred Quimby – of all people) and Fox. He spends a lot of time with Jack Alicote the editor of Film Daily who counsels Walt on the business side of the business. You see all the connections; you understand the seriousness of Walt’s situation and you ride with him trying to grasp what straws he has left. It’s hypnotic in all its detail, and it serves as a tight climax in a well written book.

This segment takes Mr. Susanin 12 pages, full of details, yet it took Mr. Barrier fewer than 2 pages in The Animated Man and fewer in Hollywood Cartoons. It took Kaufman & Merritt in Walt In Wonderland just a bit more than 2 pages to get the information across. It’s not that I needed that additional information to grasp the dire situation Disney was in, it’s that I wanted it. Yet any strong quote in Barrier’s books or Kaufman & Merritt’s has ended up in Susanin’s. It seems that ANY detail that could be found was used to tell the story.

For a geek like me who can’t get enough of this, it’s great. But I wonder about the average reader.

My only real problem with the book is that I wanted the story to go on. At least through Steamboat Willie. Susanin gives a quick sketch of the rest of Disney’s career, but I wanted to get more about that two month period when Plane Crazy was in production. After all, the staff that would leave him – Hugh Harman, Max Maxwell, Mike Marcus, Ham Hamilton and Ray Abrams – stayed on to finish the Oswald pictures while Ubbe Iwerks worked with Les Clark and Johnny Cannon to draw the first Mickey film. A real disappointment set in for me when I came to that epilogue as Disney boarded the train home to start over again.

Yet even in that epilogue there are those delicious details. All of the books personae are laid out with short bios of where they went and when they died. Everyone from Hazel Sewell to Johnny Cannon to Les Clark to Rudy Ising. What a sense of detail. I can tell you I’ll use this book for information for a long time, and there’s not doubt I’ll read it a few more times. This is a wonderful book, and I encourage you to pick it up.

There are some fine interviews with Mr. Susanin on several sites:

- Didier Ghez talks with him on his Disney History site.

- On Imaginerding there’s a nice informal interview.

- Moving Image Archive News also has a review mixed with interview.

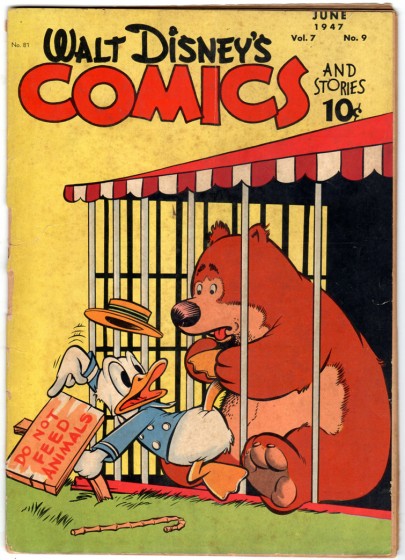

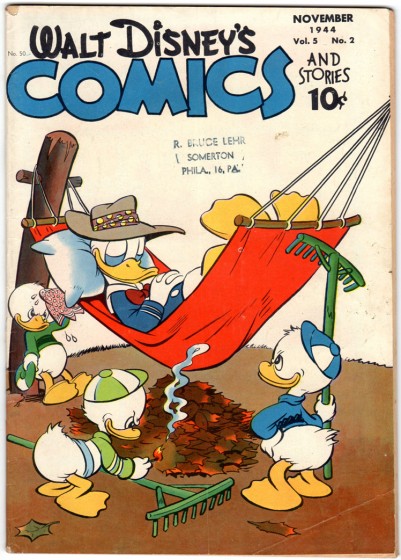

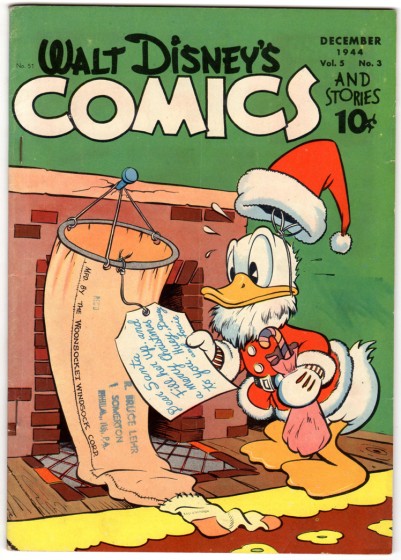

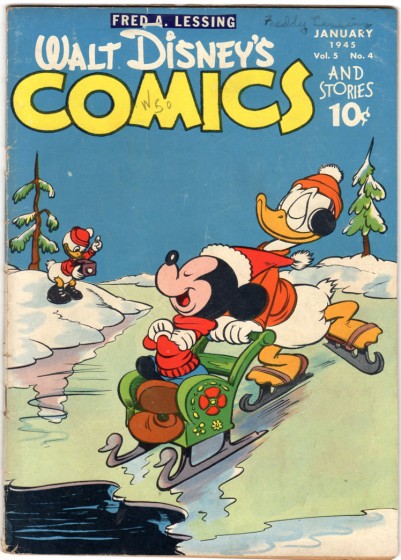

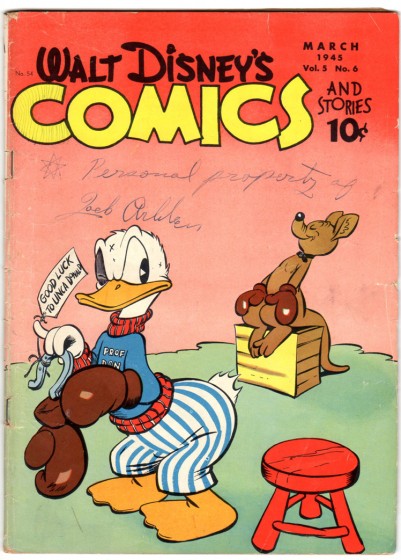

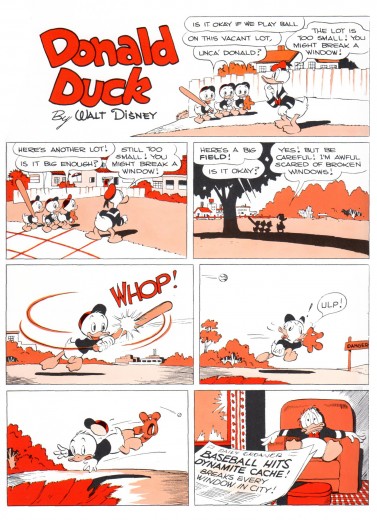

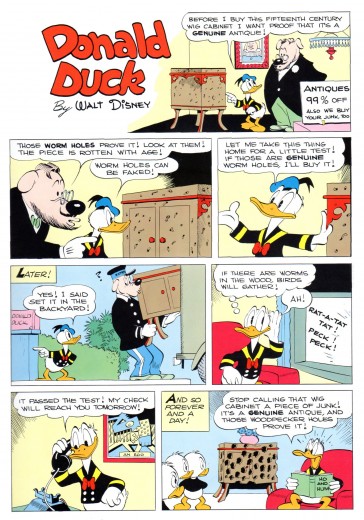

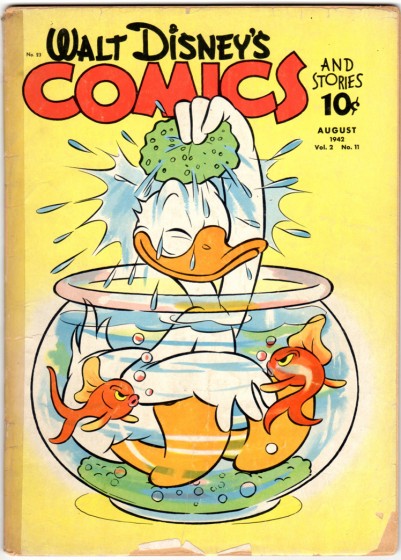

Bill Peckmann &Comic Art &Disney 05 Aug 2011 06:54 am

More Walt Kelly Disney Covers

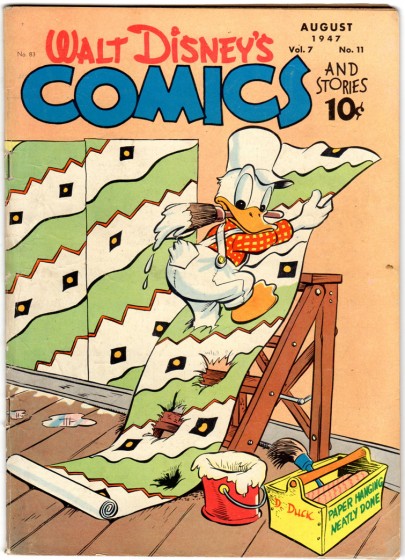

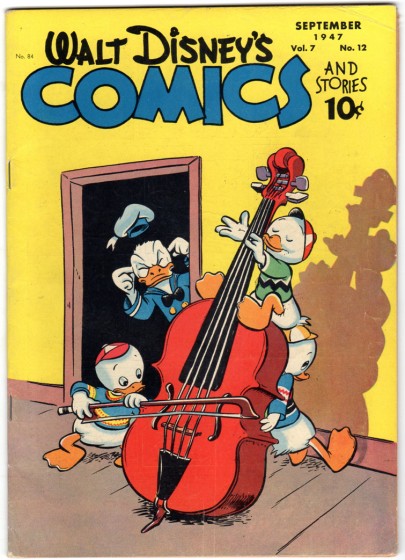

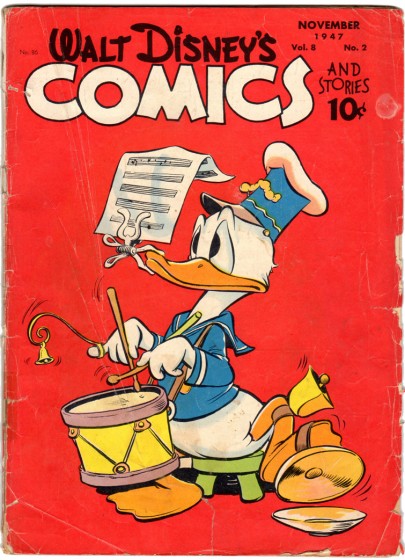

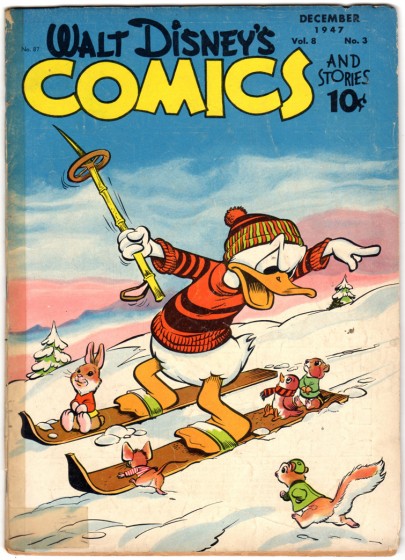

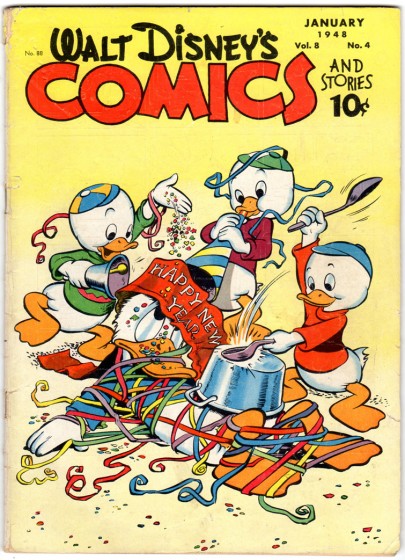

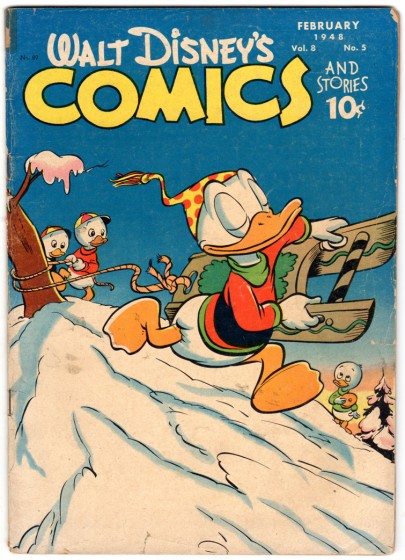

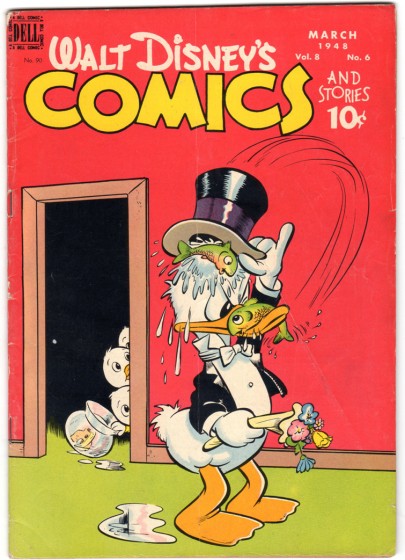

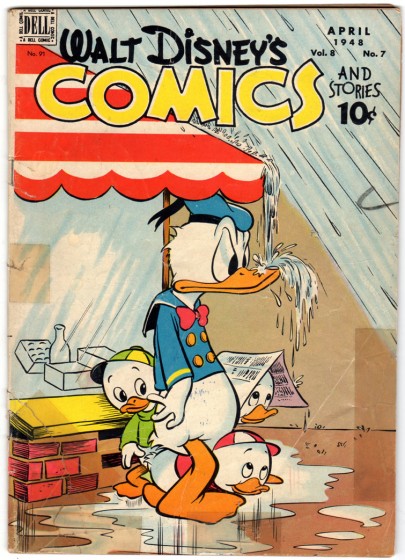

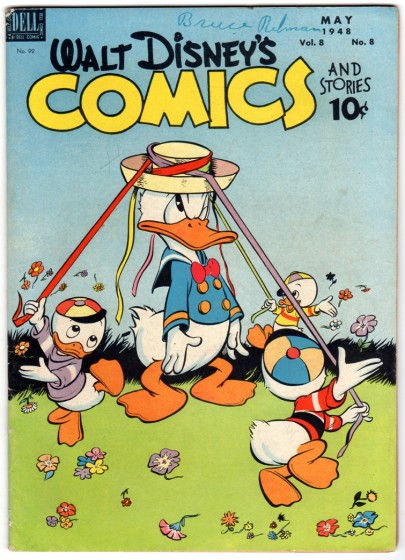

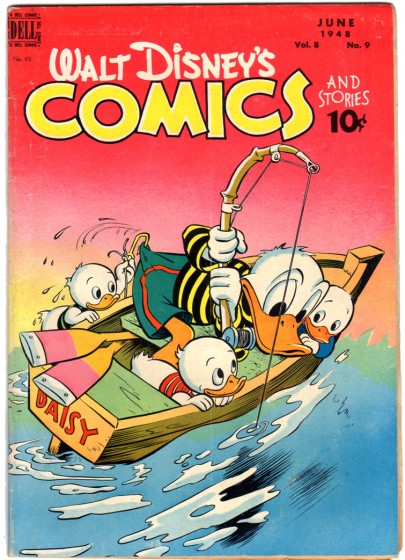

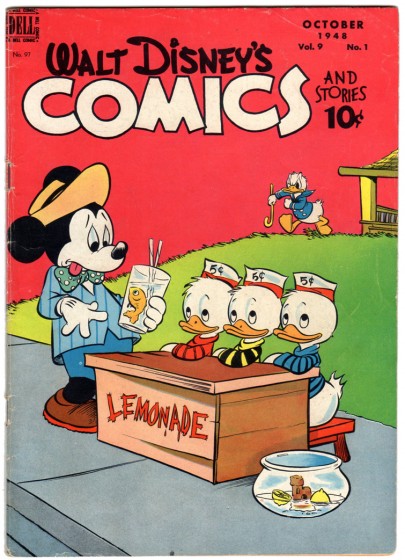

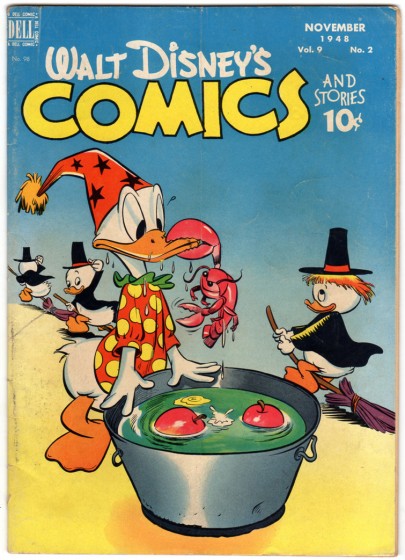

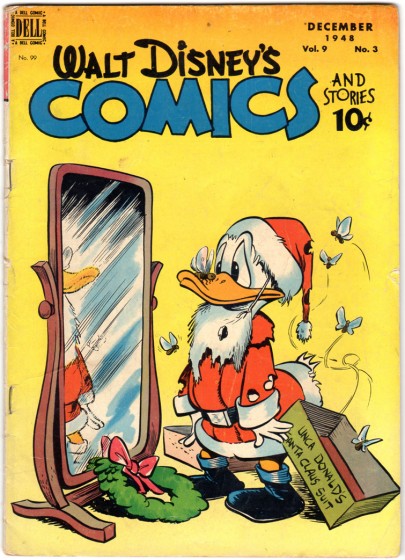

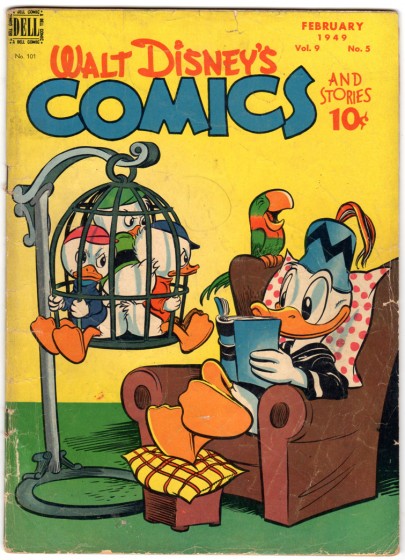

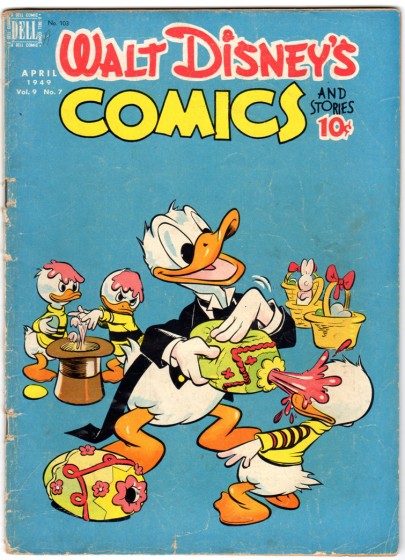

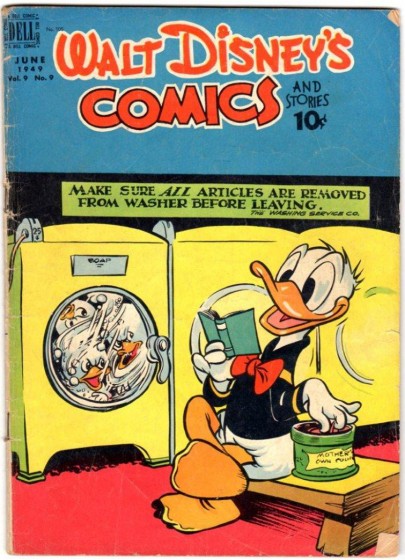

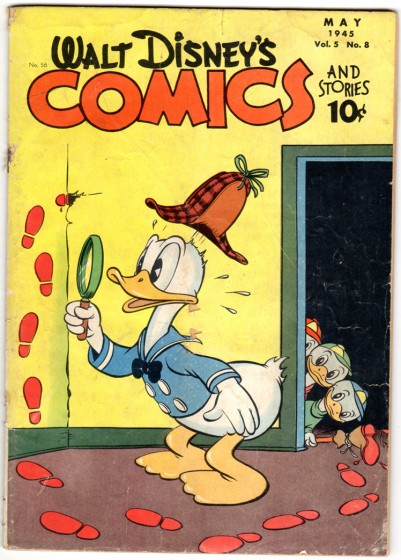

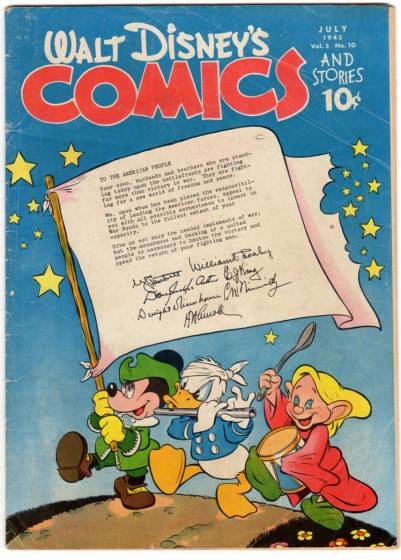

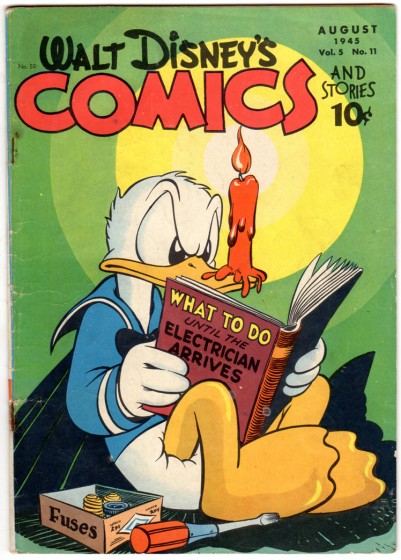

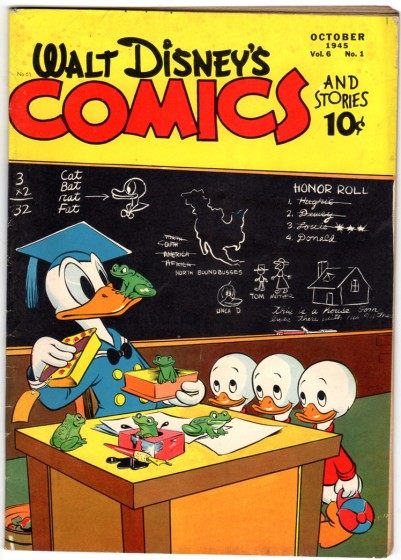

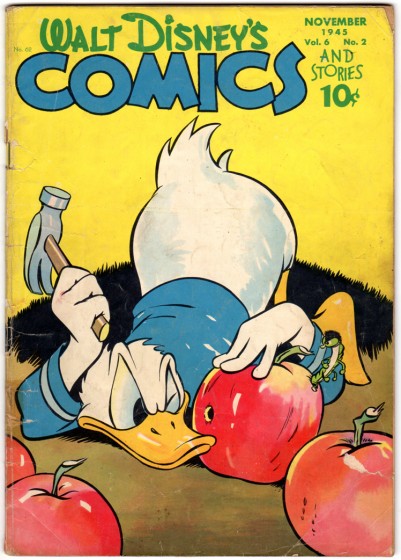

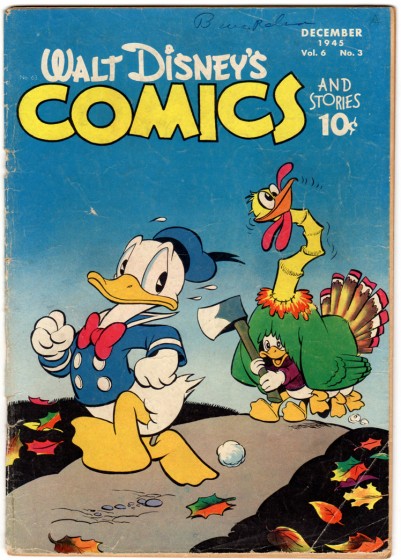

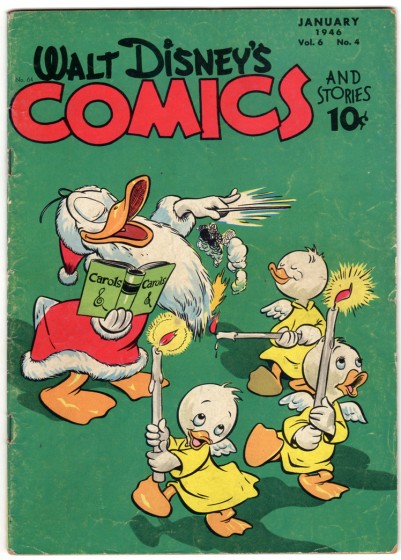

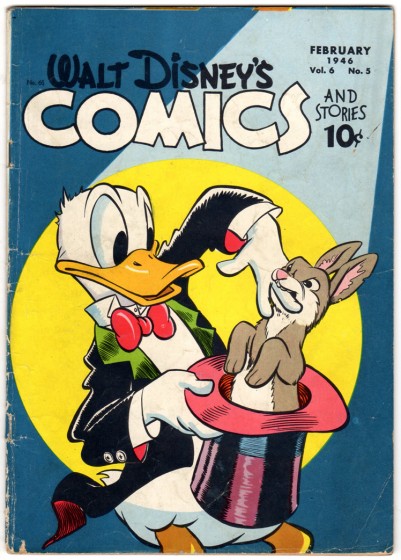

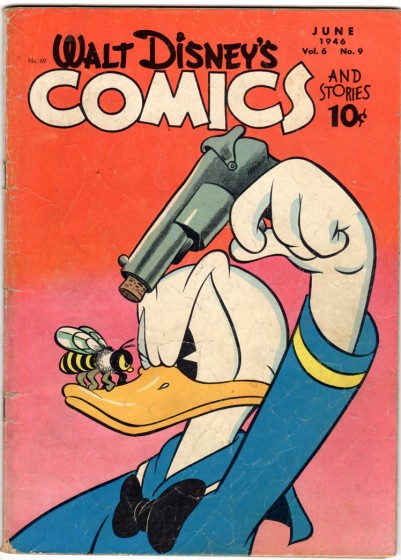

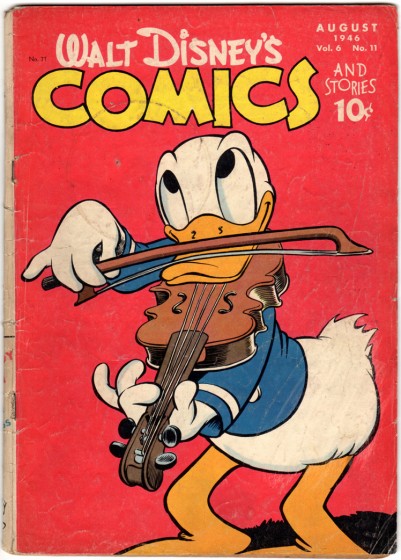

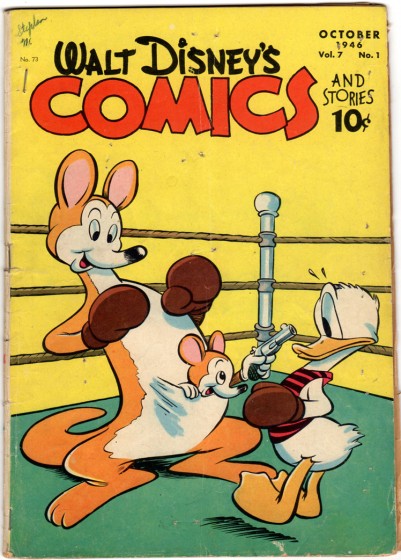

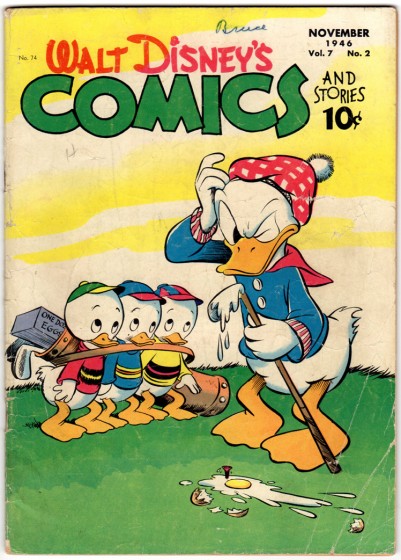

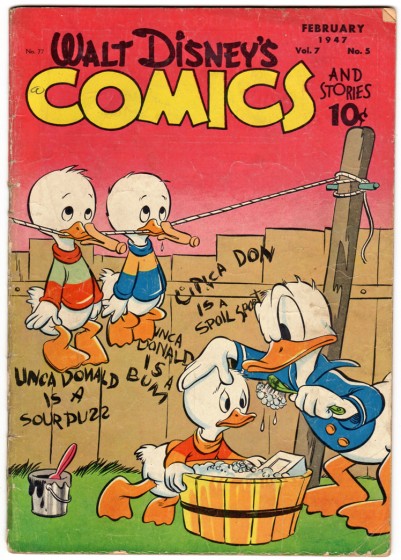

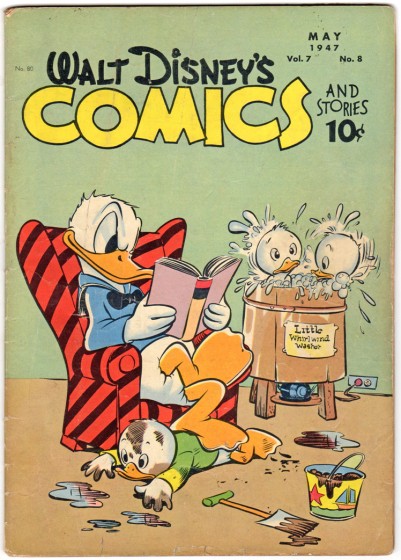

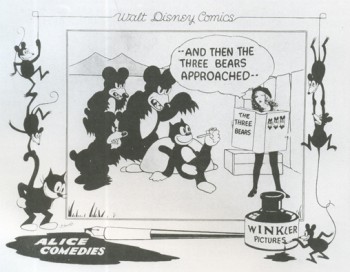

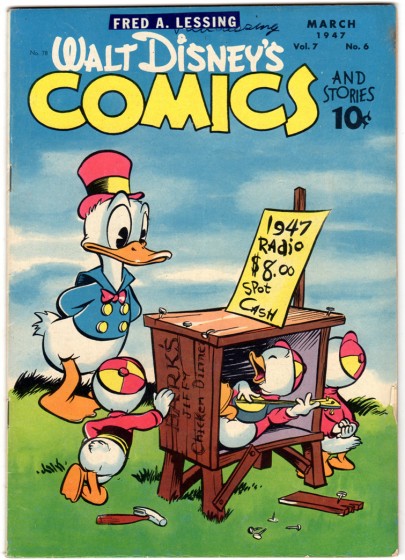

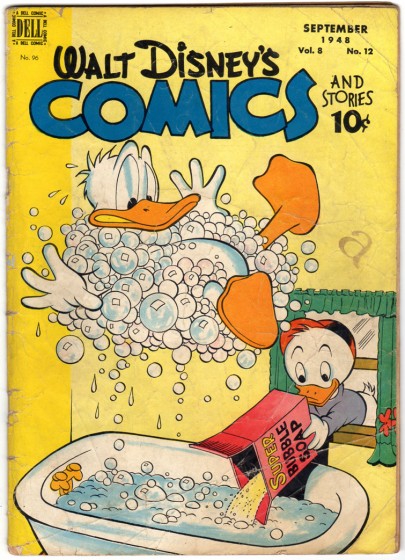

- Last week I posted a bunch of beautiful covers to Walt Disney Comics from the 40′w. For the most part they were done by Walt Kelly, and they were stunning. Here, thanks to another beautiful lode sent me by the inestimable Bill Peckmann, are some more of these wonderful covers by Kelly (except where noted). They are all gems. You can see the hint of Pogo starting to peek through in the non-Disney, secondary characters. Such clear composition and such clean design.

1

1

20

20

This is Carl Barks’ second cover that he did for “Comics and Stories”.

Many thanks, again, to Bill Peckmann for sharing his immense and invaluable collection.

Action Analysis &Disney 02 Aug 2011 08:16 am

Action Analyisis – April 19, 1937

- We return to the Disney Action Analysis notes for the classes held at the studio in after hours in early 1937. (You’ll remember that we left off with the April 5 notes that were posted out of order. Thanks to Mike Barrier contributing those notes that I didn’t have.)

Here we have the notes for April 19, 1937. Screened is a loop of a Charlie Chase action. Chase was a Vaudevillian who slipped into silent movies, became a star in the Hal Roach studios. When sound came in his star fell a bit. He performed minor roles in many films including Three Stooges comedies. He died in 1940 at the age of 46.

Taking part in this session are the following: Bill Shull, Ken Peterson, Bernie Wolfe, Roy Williams, Robert Leffingwell, Milt Neil, Joe Magro, Paul Satterfield, Jimmie Cullhane, Stan Quackenbush, Izzie Klein, Jacques Roberts, and Bill Tytla. They are definitely looking at him with the dwarfs in mind.

Here are the notes:

1

1Acts as the cover page

A small note on these documents. Some of you may have noticed that infrequent peg holes show up on some of the scans on the left side. This is because the originals were printed on 5 hole animation punched paper. A couple of the documents I’ve posted came from originals, but many of these are copies of copies and the image of the holes has vanished into the old Xerox ether.

Bill Peckmann &Comic Art &Disney 28 Jul 2011 07:07 am

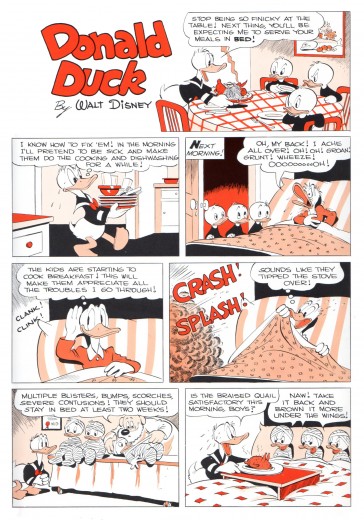

Walt Disney Comics Covers

- Bill Peckmann has sent me a stash of original comic book covers for the Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories. There are 20 in all, and they all are beautifully drawn and colored. It’s a real charge to see them; for the most part they’re the work of Walt Kelly, and it’s great to see how his comic styling develops. Bill wrote the following about them:

- The issues of “Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories” are in order of publication, it’s not a complete run but it is a fun one. Being the number one selling title of it’s day, it’s easy to see why some of the kids put their names on the covers, I’m guessing they didn’t want to lose them or trade them off by mistake. (Trading comics and bubble gum cards in those days was always going on, easy way to save money.)

All of the covers were done by Walt Kelly, except the very first one (August 1942, “Goldfish Bowl”), that was done by Al Taliaferro, long time Donald Duck newspaper strip artist.

Here are the covers from December 1945 to May 1947.

1

1(Click any image to enlarge.)

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Disney 27 Jul 2011 07:16 am

Stromboli Jump Recap

As I pointed out a couple of weeks back, I’m going forward with recap posts of the Tytla scenes I’d previously posted. They should be seen and studied often. They’re too good.

- Here’s a scene all of 29 drawings in length, but if you check it out in the film it’s enormous. Everything’s moving – the wagon they’re standing in, the pots & pans, things on the table and most definitely Stromboli who in one enormous drawing changes the scene, Pinocchio’s world and the mood in the audience. “Quiet!” is all the dialogue shouted in the scene. It”s frightening.

(Make sure you click to enlarge every drawing here.)

15

15

Closed position starting to open his body – legs first.

16

16

Pulling it all into a ball,

he shouts, “QUIET” – the dialogue for the scene

19

19

Couldn’t open up more than this.

Just look at the distortion in this drawing. Magnificent.

Open, loud, ready to burst. One frame only.

20

20

Next frame he’s landed and gathered himself.

Only the secondary action – vest, pants, beard –

echo the outburst.

24

24

His clothes lag behind in pulling themselves together.

29

29

He’s set to give the demand and end the scene.

The following QT movie represents the entire scene from Pinocchio.

Click left side of the black bar to play.Right side to watch single frame.

Here are frames from the actual scene:

1

1.

8

8.

19

19.

20

20.

26

26

What a difference the shake of the coach and the

bounce of the hanging utensils make to the scene.

There’s danger everywhere, here.

It’s scary.

Many thanks to my friend, Lou Scarborough, for the loan of this scene.

Bill Peckmann &Comic Art &Disney 26 Jul 2011 07:15 am

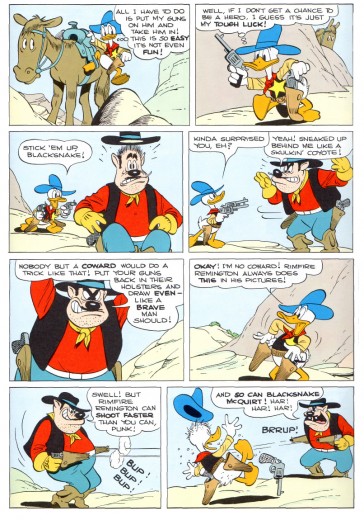

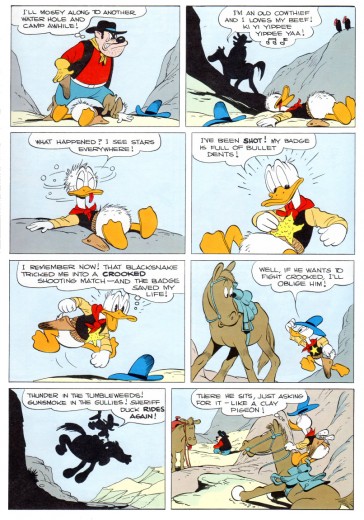

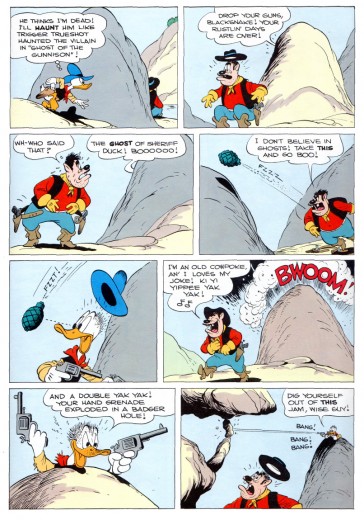

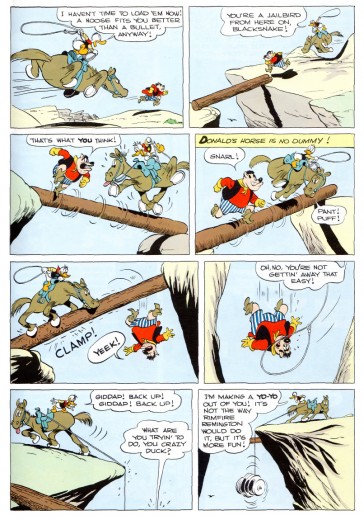

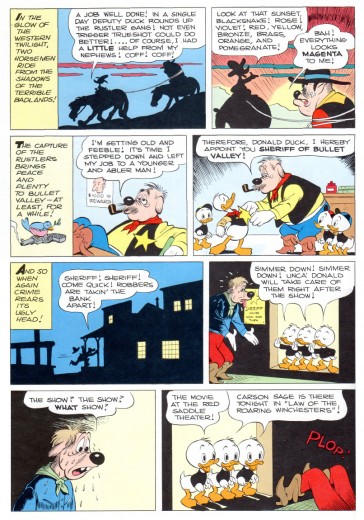

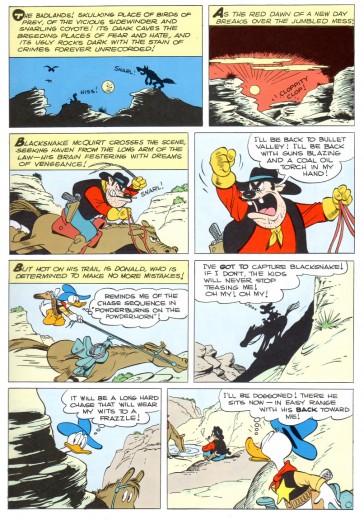

Sheriff of Bullet Valley – 3

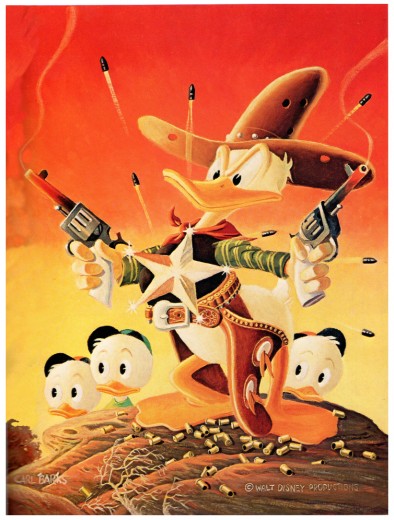

- At last, we’ve reached the final part of the Carl Barks Donald Duck story, “Sheriff of Bullet Valley”. This is one of the most treasured of the Donald comics, and thanks to Bill Peckmann‘s sending the book, we can get to see it all of a piece.

You can visit part 1 & part 2 on this blog in the past two weeks.

Let’s start with another oil painting by Carl Barks adapted from the cover of this magazine. It’s from “The Fine Art Of Walt Disney’s Donald Duck.”

“The Sheriff of Bullet Valley” (18″x24″)

The handling of this third version of Bullet Valley is close to the original comic book

cover and truly conveys the ominous atmosphere of the showdown scene.

.

Now here’s the remainder of the story, The Sheriff of Bullet Valley.

We pick up where Part 2 left off . . .

1

1

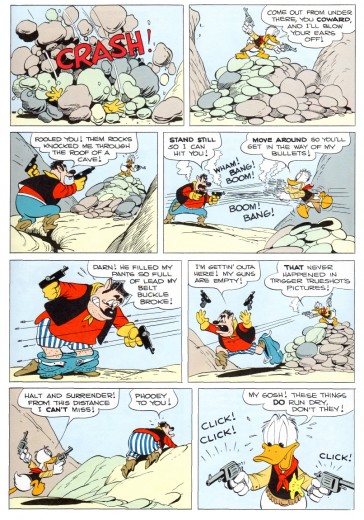

To fill out this post Bill Peckmann had sent another couple of one-page gags. Here’s his additional note:

- Here are the two end page gags done in the original two color format which looks great as well as the back cover gag done in full color, which also looks terrific. When we were kids, all of us “Good Duck Artist” fans, (Remember at that time we didn’t know the name of the cartoonist who drew our favorite DD stories) would have loved to have seen a whole DD comic printed and colored on cover stock (like back cover gags) and not on the ratty, pulp newsprint paper. Unfortunately now, when comic book reprint albums are printed on quality paper, the coloring is so ham fisted, they loose so much of the essence of the original book, especially Barks’ beautiful line work. It’s probably better to see it in it’s original black and white but then something else seems to be missing. (There are some people you just can’t seem to please!)

1

1

Thanks again to Bill Peckmann in sharing his library with us.

Disney &Frame Grabs &Layout & Design &Models 25 Jul 2011 06:53 am

The Old Mill Multiplane

- Having visited the multiplane camera scenes of SNOW WHITE, I can only see the usefulness of going to the keystone of the camera, “The Old Mill.” It’s on this lyrical and beautifully produced short that they admittedly devised the idea of testing the multiplane camera in action. However, in an interview I’ve read with director, Wilfred Jackson, we find that the camera wasn’t available for much of this film. It was being tied up with a number of shots from

- Having visited the multiplane camera scenes of SNOW WHITE, I can only see the usefulness of going to the keystone of the camera, “The Old Mill.” It’s on this lyrical and beautifully produced short that they admittedly devised the idea of testing the multiplane camera in action. However, in an interview I’ve read with director, Wilfred Jackson, we find that the camera wasn’t available for much of this film. It was being tied up with a number of shots from  SNOW WHITE. The interview is by David Johnson posted on American Artist‘s site. Here’s the passage I’d read:

SNOW WHITE. The interview is by David Johnson posted on American Artist‘s site. Here’s the passage I’d read:

- DJ: Since you worked on The Old Mill, you were involved with the multiplane camera. Can you tell me about Garity [the co-inventor] and the invention of this thing and some of the problems and miracles that it did.

WJ: What I can tell you about my experiences with it was the The Old Mill was supposed to be a test of the mutiplane, to see if it worked. Somehow, we were so held up in working on The Old Mill by assignments of animators because Snow White was in work at that time and animators that I should have had were pulled away just before I got to them and other animators were substituted because Snow White got preference on everything. And we got our scenes planned and worked out for the multiplane effects and by that time some of the sequences on Snow White were being photographed. The multiplane camera itself had all kinds of bugs in it that had to be worked out. We were held up until so late that I actually did work on another short – I don’t remember which short. I don’t even remember if I finished it up – did work on some other picture to keep myself busy while we could get facilities to go ahead on The Old Mill. By the time they had got the bugs out of the multiplane camera, they had multiplane scenes for Snow White to shoot and they got it busy on those first. Finally in order to get The Old Mill out the scenes that had been planned for multiplane had to be converted to the flat camera to do the best they could. You won’t find more than a very few multiplane scenes in The Old Mill.

DJ: I wasn’t aware of that.

WJ: I’ve had messed up schedules on pictures but I’ve never had a more messed up one than I can remember for The Old Mill.

So, of course, I’ve searched for scenes that I believe are definitely part of the shoot done on Garity’s vertical Multiplane Camera.

The film is little more than a tone poem of an animated short. It’s about as abstract a film as you’d find coming out the Disney studio in the 30s.

Let’s take a look at some frame grabs from the film, itself:

1

1We open on a slightly-out-of-focus mill with a spider’s web

filling the screen, glistening in focus, in the foreground.

2

2

The camera moves in on the mill and the

spider’s web goes out of focus and fades off.

3

3

Dissolve through to a closer shot as we move in.

4

4

Dissolve through to an even closer shot.

5

5

Foreground objects go out of focus as we move in on the mill.

7

7

Cut to a bird flying in the foreground carrying a worm.

8

8

The interior of the mill, viewed through the window, is dark grey.

9

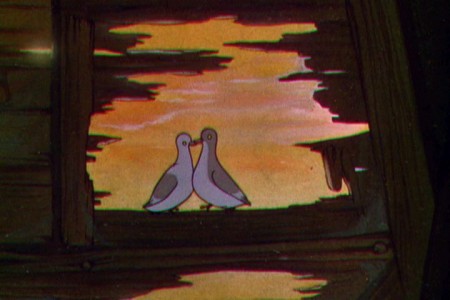

9

Dissolve into the next shot which looks as though it appears in the framed window.

Here, we cut to a long pan up the mill using the multiplane. The lighting in this scene is inconsistent. There are flares and glares and some minor jerks to the artwork. No doubt this was done on the multiplane camera, and it would have been reshot if there were time and money.

I couldn’t hook up the artwork to simulate the pan since overlays from one frame didn’t match the next. It was all moving with multiple levels (maybe five?) and they didn’t match from one frame to the next.

1

1The shot starts from the top of the mill looking down on the birds.

2

2

It starts moving up the central column.

6

6

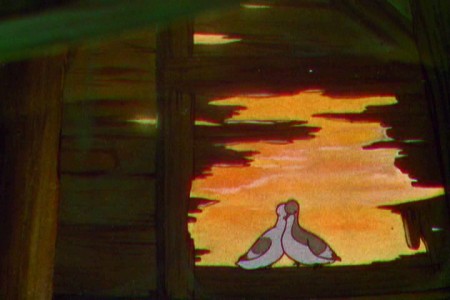

Stopping on a pair of lovebirds.

7

7

The camera continues upward.

At this point there is a cut outside to bats fleeing the Old Mill for the night.

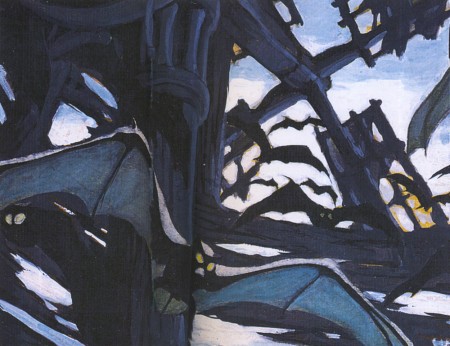

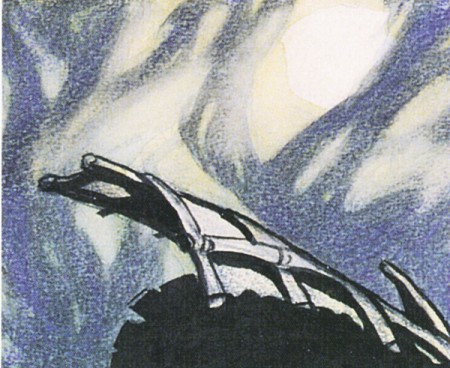

Gustaf Tenggren made some preproduction drawings of this scene which can be found in John Canemaker‘s book, Before the Animation Begins which in itself is something of a tone poem of a book devoted to many of the designers at the Disney studio.

1

1

Now here are frame grabs from the film, itself.

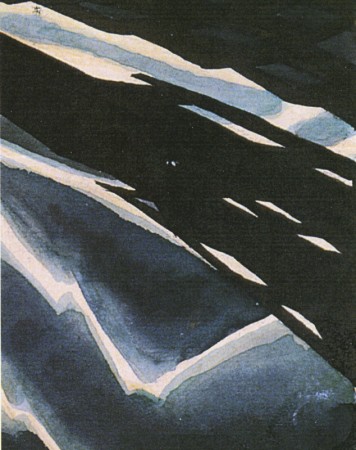

1

1

4

4

The multiplane camera is used only for the exterior shots of the mill

shown over the course of a number of scenes.

5

5

Placed as I’ve done with them, they look as though

they’re one continuous scene over the length of the storm.

21

21

Finally, things settle down and the camera comes to

the Old Mill at rest in the morning.