Category ArchiveLayout & Design

Bill Peckmann &commercial animation &Independent Animation &Layout & Design 27 Mar 2012 07:10 am

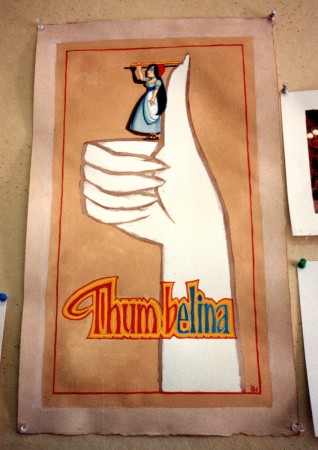

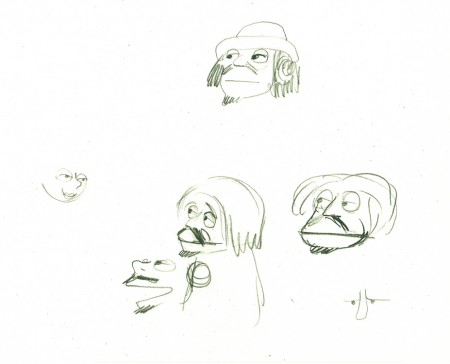

Thumbelina Photos

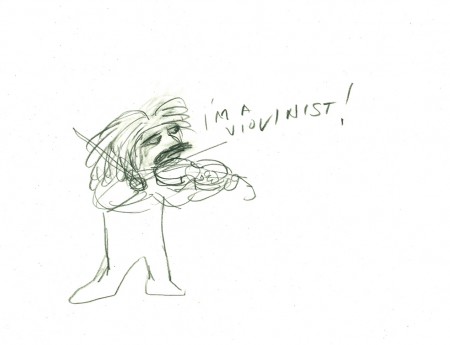

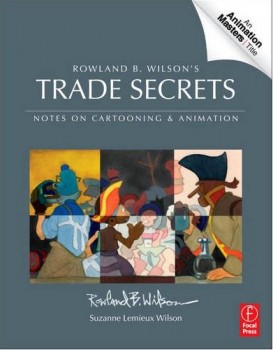

- There’s a wonderful new book on the market, and I want to keep it in your attention. So I’m trying to give as much attention to the great work of Rowland B. Wilson.

- There’s a wonderful new book on the market, and I want to keep it in your attention. So I’m trying to give as much attention to the great work of Rowland B. Wilson.

Rowland B. Wilson’s Trade Secrets: Notes for Cartooning and Animation seems to offer quite a bit of attention to Mr. wilson’s animatoin art as it does his brilliant illustration and cartooning.

Keep it in mind.

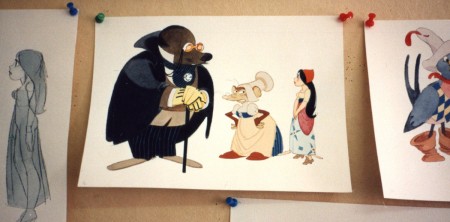

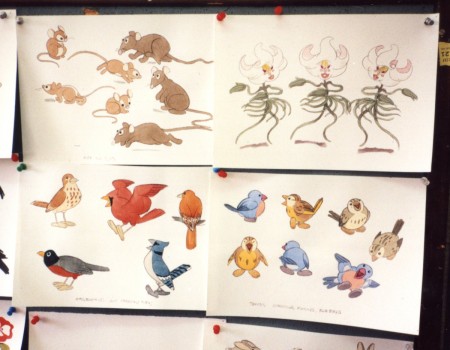

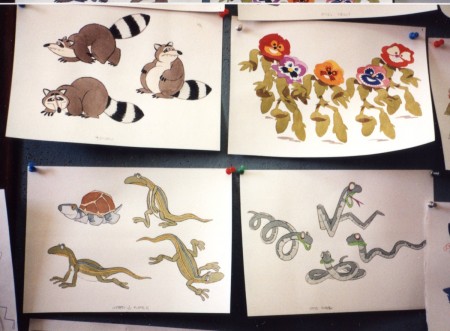

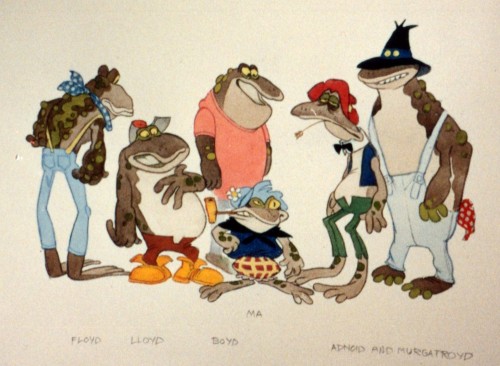

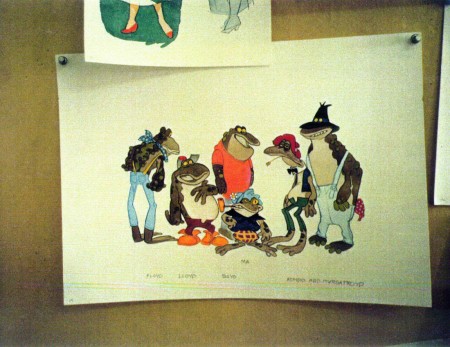

- Yesterday, we saw a lot of B&W models by Rowland B. Wilson done for Don Bluth‘s feature, Thumbelina. Today, I have a cache of photos taken by animation producer, Phil Kimmelman, when he visited Rowland in Ireland. Many of the models overlap, except that these are in color.

These all come by way of Bill Peckmann‘s great collection, thank you very much.

1

1Rowland at his desk.

18

18

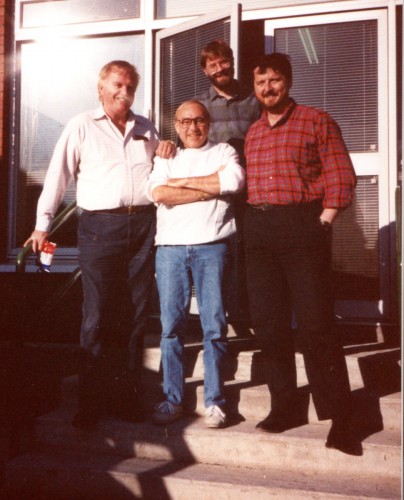

Rowland (L), Phil Kimmelman (Ctr)

Bill Frake (R), unknown in rear

Animation Artifacts &Bill Peckmann &Illustration &Layout & Design &Models &repeated posts &Rowland B. Wilson 26 Mar 2012 07:23 am

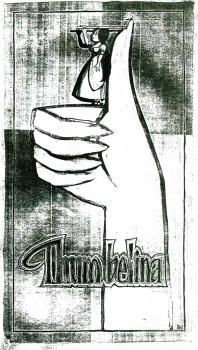

Thumbelina from Rowland B. Wilson

- Thanks to Bill Peckmann‘s extraordinary collection of design material, I have access to quite a few model sheets by Rowland B. Wilson.

- Thanks to Bill Peckmann‘s extraordinary collection of design material, I have access to quite a few model sheets by Rowland B. Wilson.

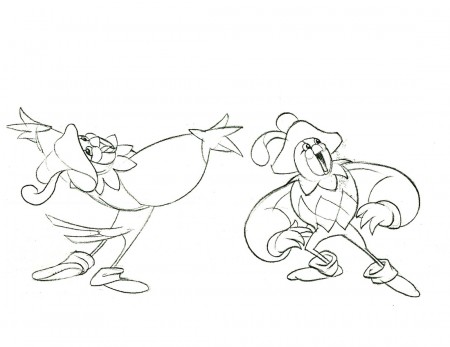

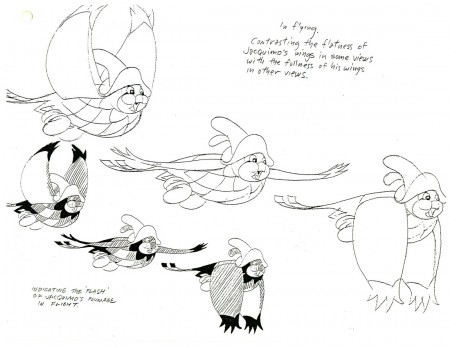

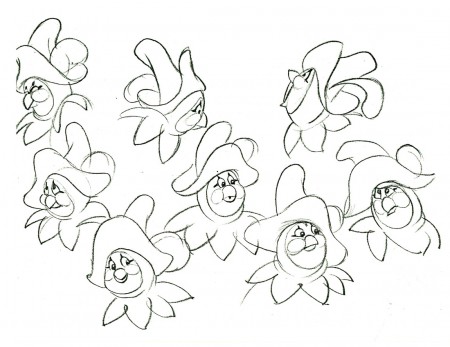

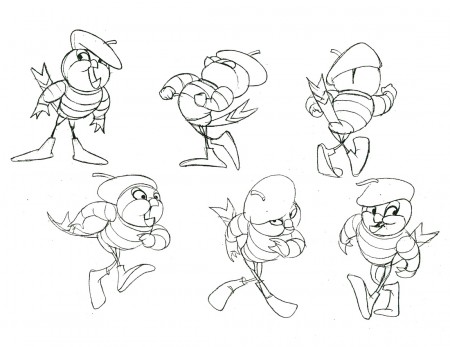

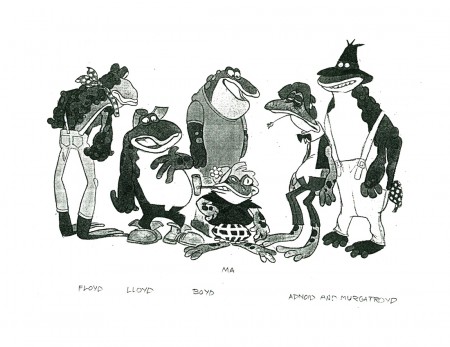

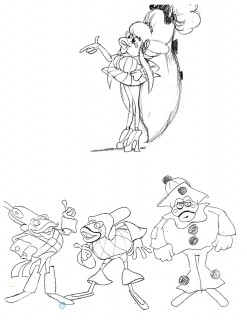

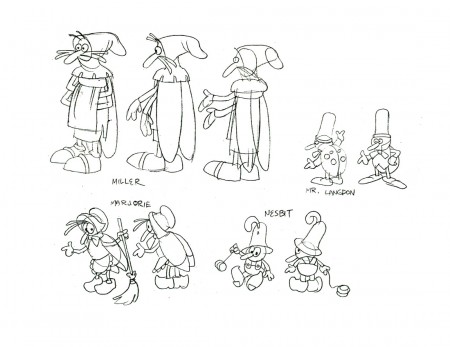

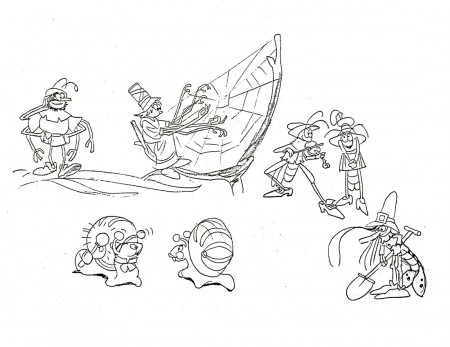

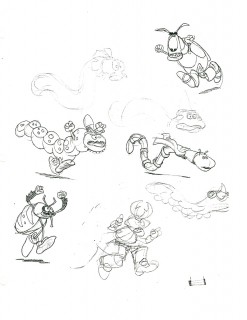

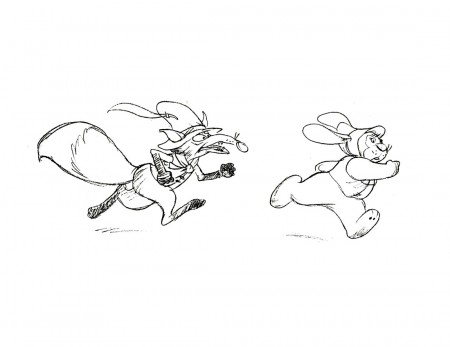

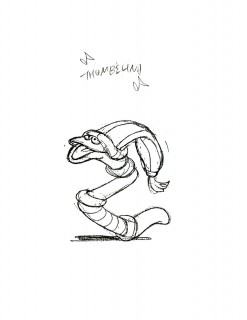

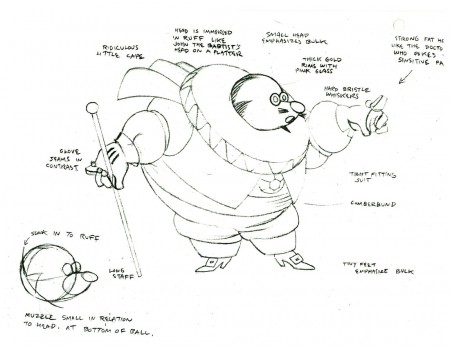

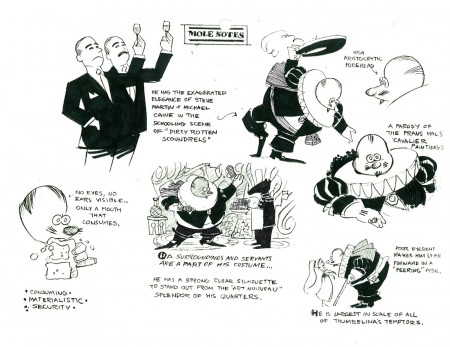

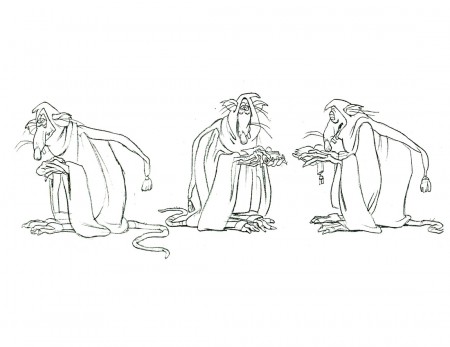

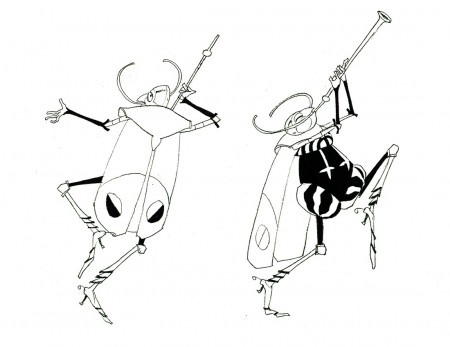

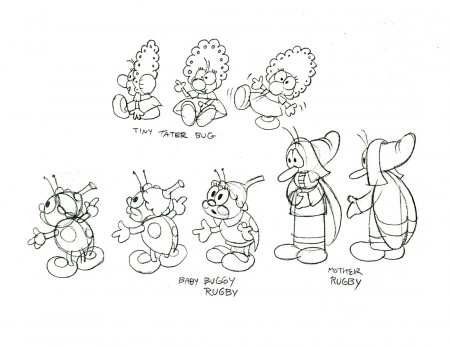

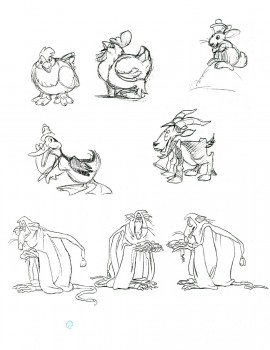

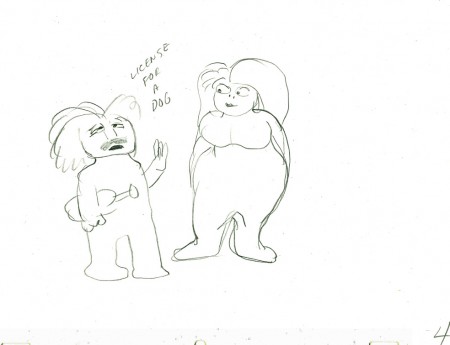

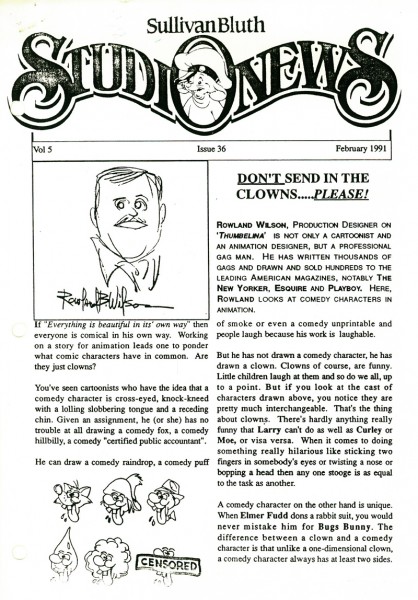

His models for Don Bluth‘s feature, Thumbelina, fill a binder. I’m gong to have to break it up into two posts.

Here, I’ll reproduce the article Rowland had written for the in-house organ “Studio News.” This follows with models for some of the lead character models.

These models were done in pencil and ink, sometimes in color. Unfortunately, all of these are 8½ x 11 xerox copies. Blacks wash out and washes blacken. Regardless, they all come across fine enough to get the idea.

Any feature takes a lot of work. You can understand that just in the large number of model sheets that grace the production. When you have a talented artist such as Rowland Wilson doing that modelling for you, your art is off to a good start.

1

1(Click any image to enlarge.)

1

1

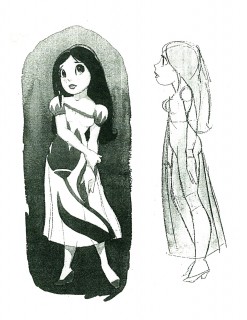

Here we have the model that Rowland drew for Thumbelina.

This is definitely not the rotoscoped princess that we saw in the film.

2

2  3

3

Here we have a lot of different costumes Thumbelina

will wear as she travels on her expeditions.

4

4  5

5

An original idea – a character who wears

more than one costume in a film!

This film is far from the best of Don Bluth, but it goes to show how much solid work is done for any feature film. There’s also quite a bit to be learned from any feature. Many of these models didn’t end up in the film (take a look at Thumbelina herself in yesterday’s post) but the drive was a forward one.

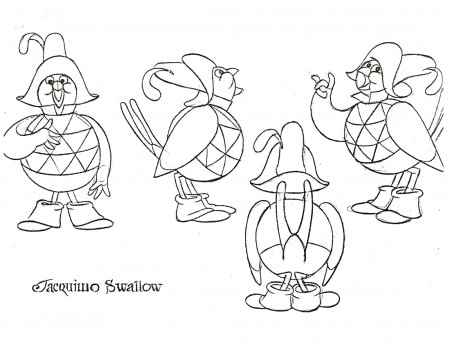

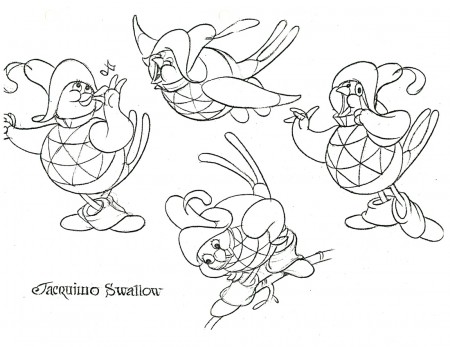

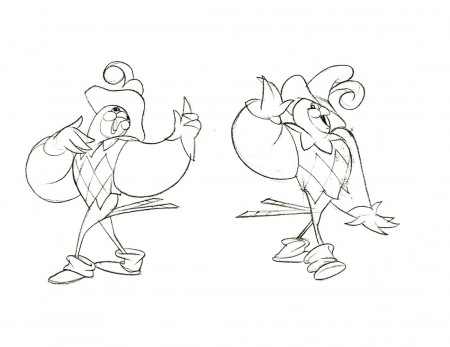

Off to the modelshow:

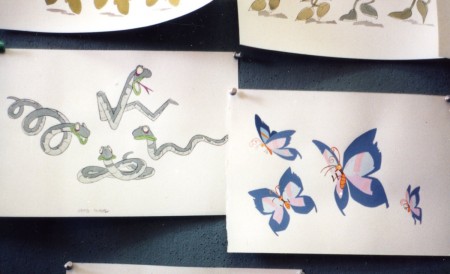

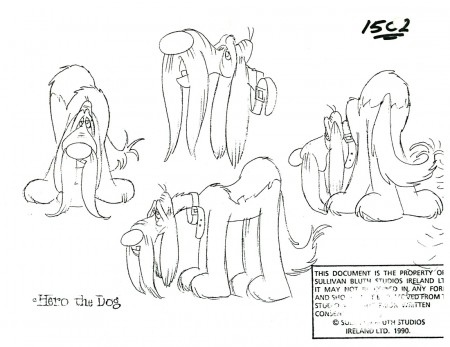

1

1

(Click any image to enlarge.)

3

3

Another color one copied in B&W

30

30

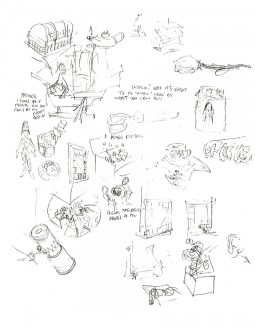

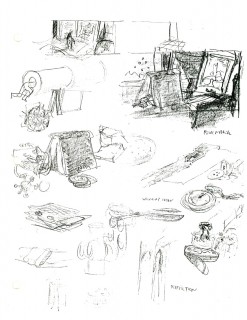

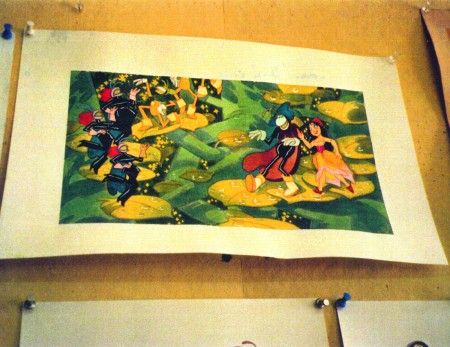

Finally, here are two color photos Rowland took of his presentation art.

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Disney &Layout & Design 01 Feb 2012 07:47 am

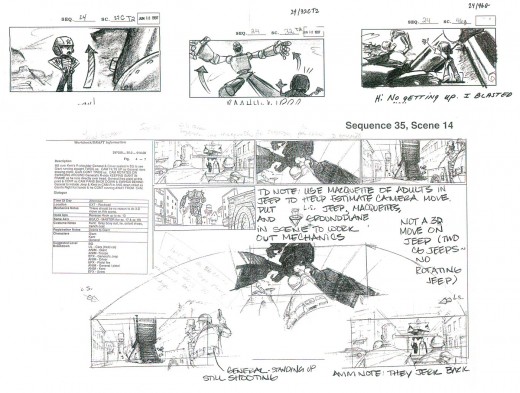

Roger – Scene 45 -part 2

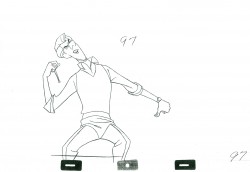

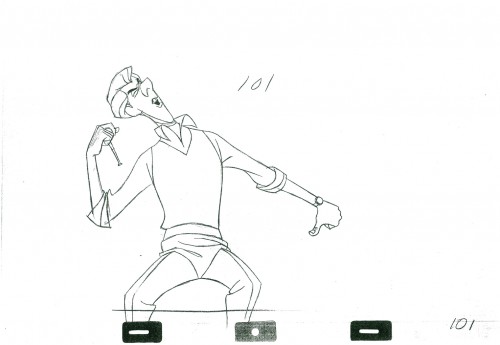

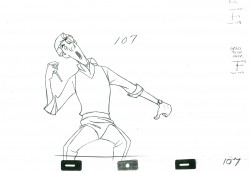

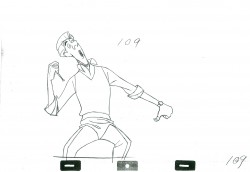

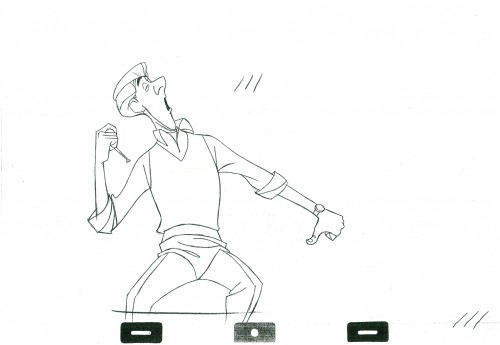

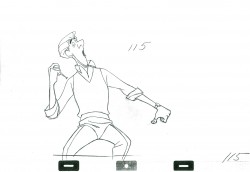

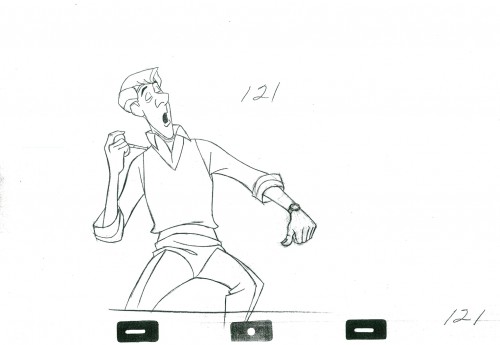

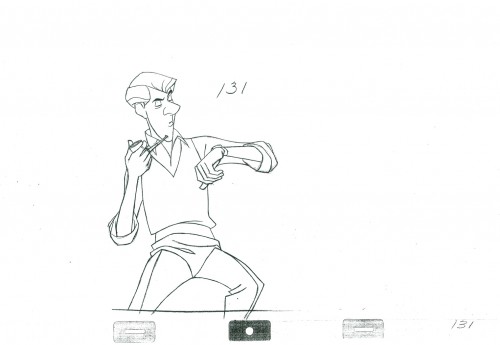

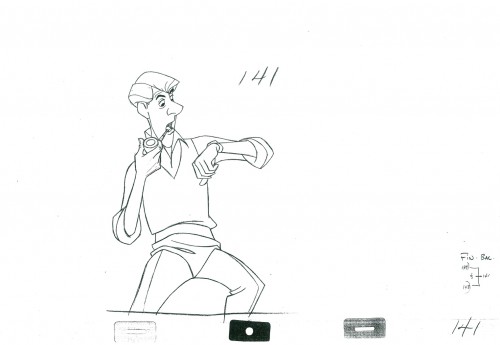

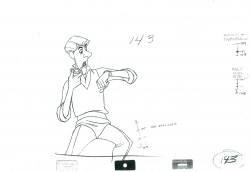

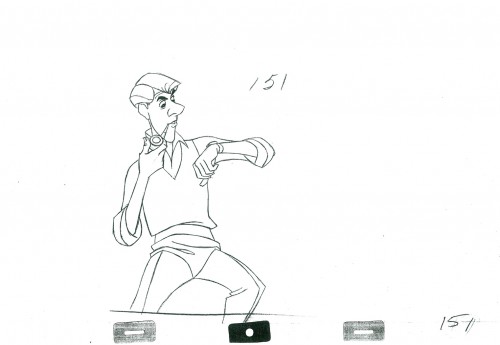

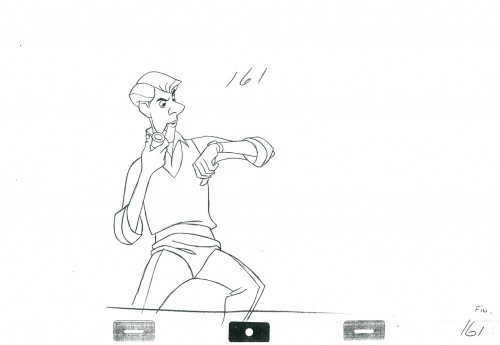

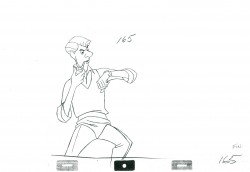

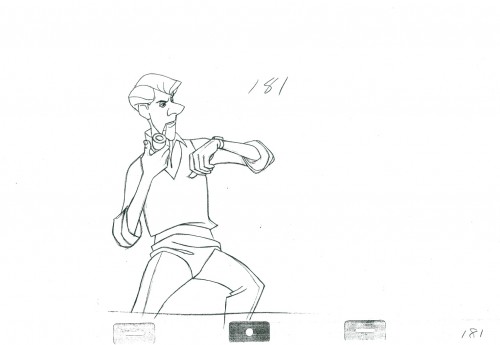

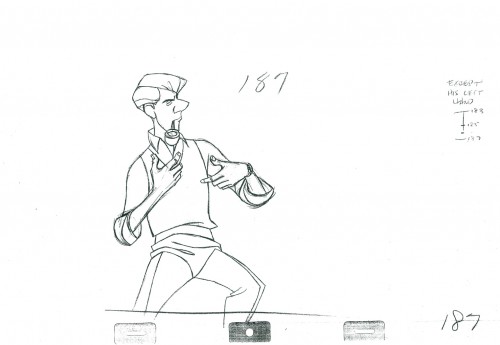

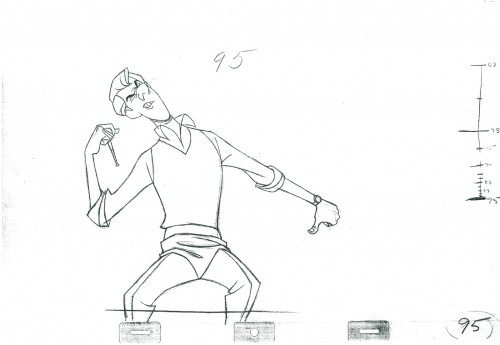

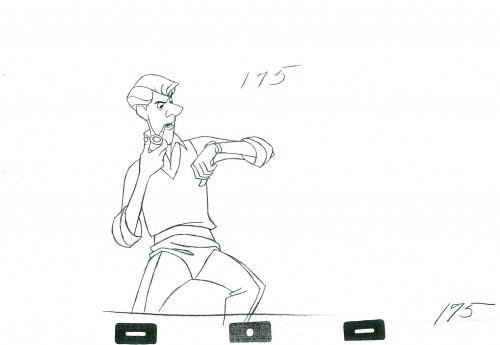

- Here is the second part of this scene from 101 Dalmatians. Roger is at the piano; Pongo has moved the mantle clock ahead by a ½ hour. Roger turns, yawns and checks his watch against the clock.

- Here is the second part of this scene from 101 Dalmatians. Roger is at the piano; Pongo has moved the mantle clock ahead by a ½ hour. Roger turns, yawns and checks his watch against the clock.

Milt Kahl animated Roger. Bill Peet did the storyboard drawing to the right. (In fact, he did the entire storyboard by himself.) This is the first of four scenes, I’ll post here – Sequence 1 Scene 45. The animation is, for the most part, on twos. There are a couple of ones at the very end ot the scene as Roger shakes his wrist. (Much of the rest of that will come with the conclusion, next week.

We start today with the last drawing from the first post.

95

95

175

175

An inbetween is missing from this part.

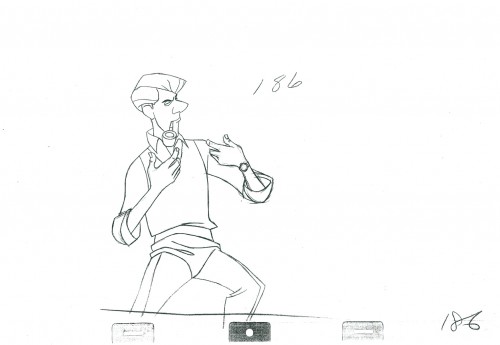

186

186

The goes on ones for a few frames as Roger shakes his wrist.

______________________

The following QT incorporates all the drawings from

this post and those in Part 1 as well.

All posts will be combined in the final piece.

All drawings were exposed on twos unless indicated otherwise.

The registration is a bit loose. Sorry but, these are copies ofcopies and there’s plenty of shrinkage.

Completion of the scene will come next week.

.

For more on 101 Dalmatians check out the animator drafts on Hans Perk‘s great and resourceful site, A Film LA. Hans has also posted Bill Peet‘s story treatment for the film several years ago. See it here.

For a look at the art direction of the film including some beautiful reconstructions of the BGs as well as some of the BG layouts go to Hans Bacher‘s great site One1More2Time3.

Andreas Deja has one of the more extraordinary blogs to visit. He just posted some beautiful drawings by some of the key animators on 101 Dalmatians as they set about to find the characters. See them here as well as a comparison of Milt Kahl‘s characters against Bill Peet‘s version. here

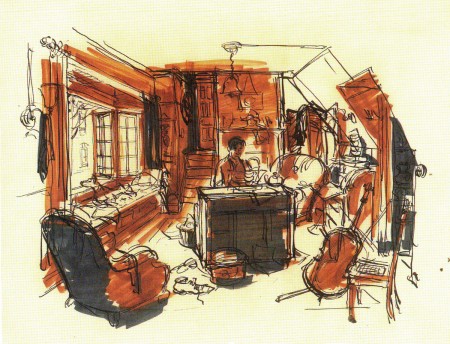

For those who own Fraser MacLean‘s excellent book, Setting the Scene, you’ll know that on pages 182-188 there’s an extensive discussion of this opening sequence from the film with plenty of beautiful images of the set.

Ken Anderson’s sketch of the room.

Articles on Animation &Independent Animation &Layout & Design 17 Jan 2012 07:00 am

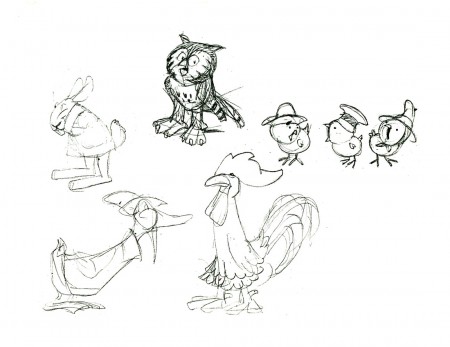

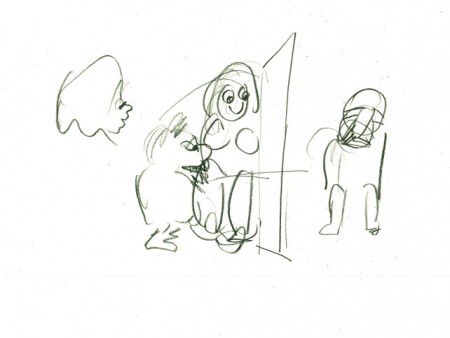

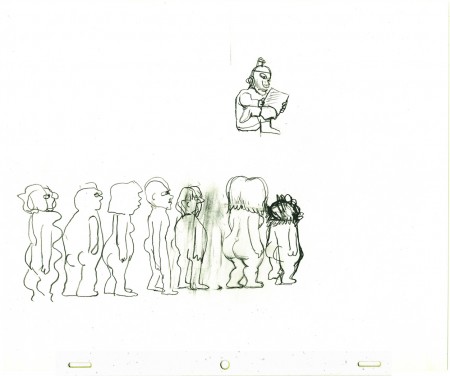

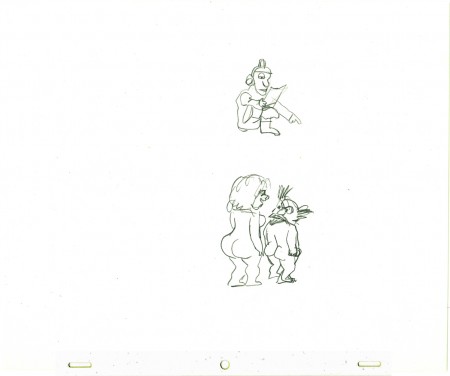

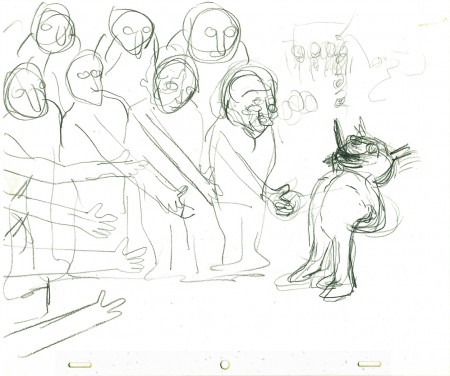

Designing Animal Farm

Chris Rushworth, whose site AnimalFarmWorld, is dedicated to the collection of material about and from the Halas & Batchelor feature animated film, Animal Farm, has sent me an article he’s found and which I thought extraordinarily interesting. It’s from a UK publication called “Art & Industry” dated September 1953.

Since there were difficulties with the scans, I had to retype the article so it could be legible and I played with the images in photoshop trying to bring some clarity to the sketches. I think they work well enough for this posting.

Geoffrey Martin, a senior member of the design team of the

Halas & Batchelor Cartoon Studios, describes his work on the production

of George Orwell’s ANIMAL FARM as a full-length feature cartoon film.

The painter and the film and stage designer work with similar motives but from varying standpoints. One one hand, the painter needs only to justify himself, while on the other, the work of the designer must fit within the framework of another man’s concept. The painter is more or less free to stand apart, and need not e called upon to explain his motives or analyze his emotions. The designer, to achieve his ends is dependent on others, and must therefore rationalize and be able to explain every nuance of his work in order to amplify the trends and emotions in a story and convey them to an audience.

The principles of designing a cartoon film are little different from those involved in a live-action film, With the obvious difference of the medium and its flat dimension, the other elements involved derive purely from the mechanics of animation. Both films set out to tell a story, to corner an idea, and to induce a reaction from the audience.

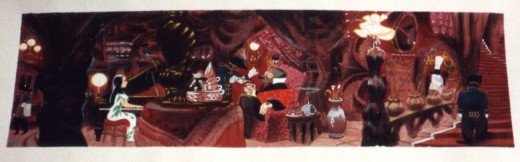

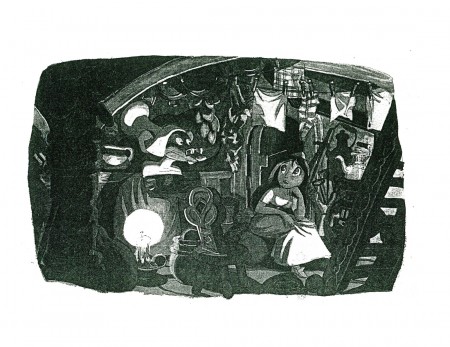

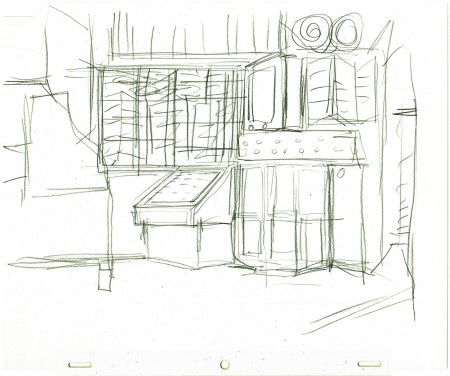

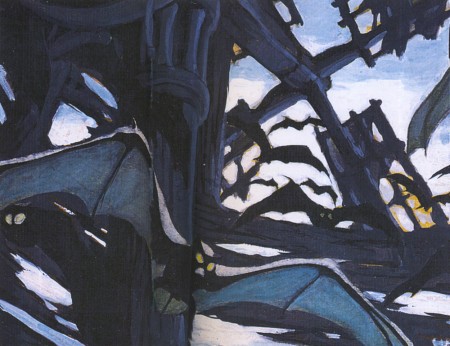

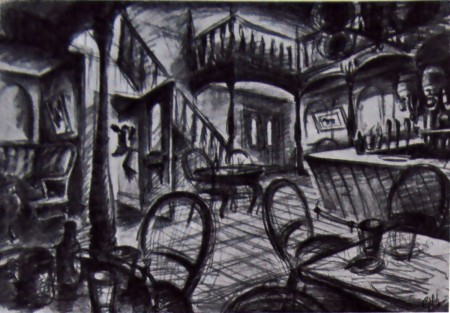

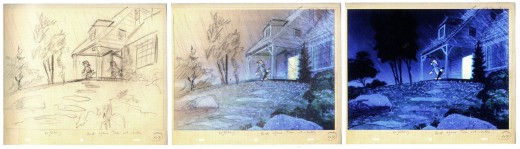

One of Geoffrey Martin’s rough atmosphere sketches

embodying his conception of the farm in relation to the story

in which the animals revolt and dispossess the farmer. The

mood of Orwell’s political satire is excellently captured in this scene.

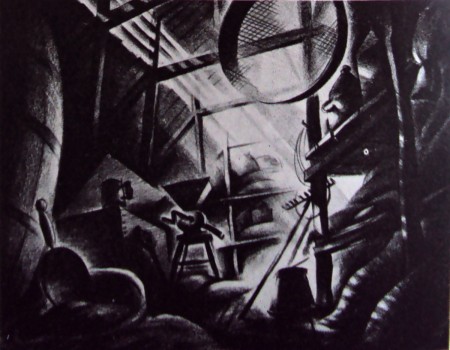

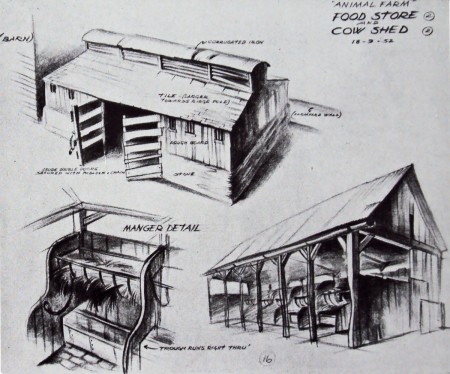

This sketch shows a corner in the farm’s food store

and was created to suggest possible props.

The cartoon designer is, if anything, more directly concerned with, and responsible for, the graphic impression on the screen than the art director in a live-action studio. To him falls the choice of angle of every sot and the responsibility of ensuring that the angle cuts smoothly to another, while constantly preserving the audience’s sense of time and place.

Once having designed and built his settings, the art director on the live-action film is largely in the hands of the director and his lighting cameraman; on these people depends how much of his original attempt is retained in the finished film. It is in this respect that the cartoon set designer is more fortunate; he has much more control over his medium, and is able to assess the result of his work more immediately by seeing the designs in actual use soon after leaving his drawing-board.

Above: The final interpretation of the scene shown opposite

painted by Matvyn Wright, principal background artist on the

production. Colour heightens the dramatic impact of the scene.

Until comparatively recent years, cartoon films were more or less and American monoply, but just ten years ago John Halas and his wife, Joy Batchelor, set up in London what is to-day the largest cartoon production group in Europe. Wisely, perhaps, they never attempted to emulate the exuberant style of M.G.M.’s ‘Tom and Jerry’ and others who work in similar vein, and as far as the feature field was concerned, Walt Disney, with his lavish and technically superb productions, reigned supreme. Instead, the concentrated on an entertaining series of educational and sponsored subjects with a definite adult flavour.

In late 1951, American producer Louis de Rochemont (‘The House on 92nd Street,’ ‘Boomerang,’ and ‘The March of Time’ series) asked the Halas and Batchelor studios to prepare an animated version of George Orwell’s sharp-edged political satire, Animal Farm. De Rochemont felt the studios to possess a style markedly different from their American counterparts – a style eminently suited, moreover, to what was, to all intents and purposes, a paradox, a ‘serious’ cartoon.

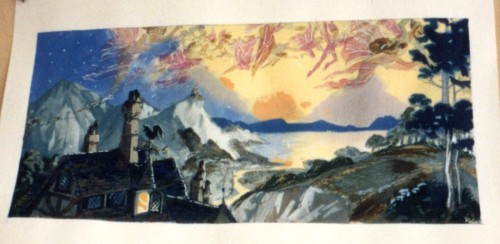

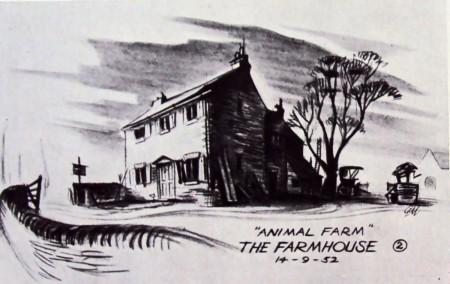

Above: Winter landscape. The half completed windmill

and the farmhouse are shown in this sketch suggesting

the starkness and economy of the settings.

When the studios first embarked on the subject, I was, as a designer, faced with many new problems. For although I possessed considerable experience of short films, Animal Farm was the first feature cartoon to be produced in this country and in length alone, was something completely new to me.

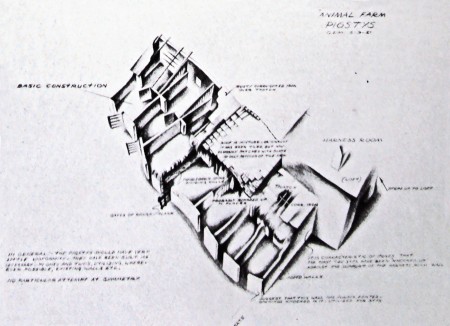

A first attempt to specify the

general style of the farmhouse.

After discussing the story with John Halas and Joy Batchelor, I made a considerable number of atmosphere sketches and rough plans. In these, I attempted to embody our many ideas regarding the conception of the farm in relation to the story.

On reading the book, I had been impressed by the windswept starkness of the farm-qualities contrasting strongly with the warm normality of the local Inn and the village, representing the outside world. We decided that the coulour would eventually go a long way towards emphasizing the contrast between those two main locations.

Since much of the designer’s work is dependent on other departments, I feel that at this point it would be well to describe the production processes of a cartoon studio. Firstly, a word here about animation, itself. In the layman’s view the animator merely ‘makes the characters move’. He does more than that, in effect, he is the very ‘life’ of the film. To make a character move does one thing, but to invest him with the spark of life and a distinct personality is a major achievement, and an element nowadays too often taken for granted.

Audiences have become accustomed to such miracles. Without character there can be no story; the characters within a play are the play. A cartoon film needs a gifted team of animators to bring life and conviction to the characters, and on their work it stands or falls.

To return to actual production, however, the story is broken down into convenient sequences to facilitate handling. In Animal Farm, we have 18 sequences, varying between three and four minutes of screen time each; this represents some 6,400 feet of film in all.

The animation director, who is to the cartoon what the choreographer is to the dance, must then time the action of each scene with stopwatch and metronome. The entire action is planned against a musical score, and to various tempi: so many bars per minute and hence per foot of film.

It is here that the designer enters the picture again. He must work to present the action the director has visualized in the most direct way possible. His department must produce the layout of each scene and the finished drawings of the settings – including sketches of the characters and their size in relation to their settings and notations as to camera movements within the scene.

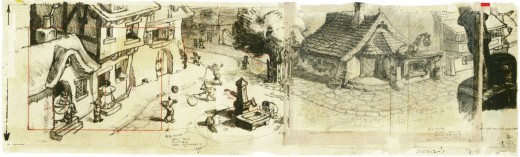

A panoramic view of the farm – used to establish

the relationship of the outbuildings to the farmhouse.

Sets of the drawings are then passed to the animation team responsible for the sequence. On completion of the work, a test shot is made of their rough drawings.

This test is checked and corrected to refine and smooth out the action. I no drastic alterations are required, the layout drawings are passed to the background department who render them in colour. The animation is traced on to sheets of celluloid and coloured with opaque paint, and the characters on the ‘cells’ are finally united with their appropriate backgrounds under the Technicolor camera.

In planning the finished layout of each scene and staging each individual piece of action, we sometimes found that perhaps the story-line demanded a change in the location of a basic set. Having solved such a problem quite happily, we might then have to rearrange our set as it was originally a demand imposed, perhaps by a later sequence.

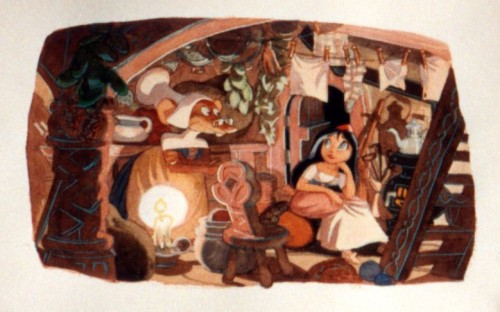

Tentative design for the interior of the village inn.

There is, in fact, a period in every cartoon film when the settings are in a continual state of change and compromise. The designer must bear in mind all the miscellaneous action which takes place in any given location throughout the film and work with this in mind.

The live-action film director is at an advantage in that once his sets are built, the are constant. He can modifu his ideas about camera angles as he goes along. But for us, any slight change of angle withina setting means a new drawing and it is quite possible to accumulate ten or fifteen layouts featuring the same doorway from various angles -made simply in order to stage differing pieces of action.

Such a process involves problems of continuity, for in each drawing ever stone and subtlety of texture must be identical from each angle. Inevitably, it becomes necessary to simplify in order to reduce the amount of work in reproducing every detail; pet ideas are swept away, and like any artist, one is sometimes reluctant to change what one feels to be an eminently satisfactory piece of design. But hard as this may be, there s the final satisfaction of knowing that one’s sets are completely workable.

Another atmosphere sketch depicting

the general appearance of the pigstys.

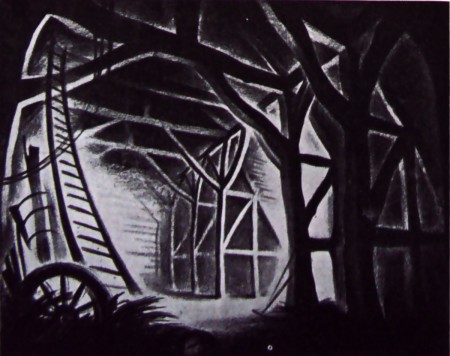

Interior of the great barn, the mise-en-scène

for the planning of the revolution.

Adaptability is, I feel, the first requisite of any setting, whether for stage, film or cartoon. Admittedly, it must carry the fight amount of atmospheric quality, but this must never hamper or dominate the actors – it is essentially a mounting, yet strong enough to be felt by the audience.

Designs establishing the appearance of farm outbuildings

and a detail of one of the mangers.

One of the main problems of designing for Animal Farm has been that the action takes place over a period of years. We have been faced with the problem of reproducing the same settings time and time again – sometimes in bright sunshine, and sometimes, in the depth of winter. It is here that the designer depends very greatly on the background department, and in Matvyn Wright, the principal background artist ont he production, we have been very fortunate. He has a reat feeling for mood and overal texture – qualities with which each of his paintings is invested. It is ovious, of course, that the background painters can make or mar the designer’s work; the effects striven for can be over-stated or lost completely. As an artist he is in the unenviable position of having to work on second-hand ideas. The initial conception is not his, only the interpretation. So often our first rough sketches have a life and excitement that is hard to reproduce.

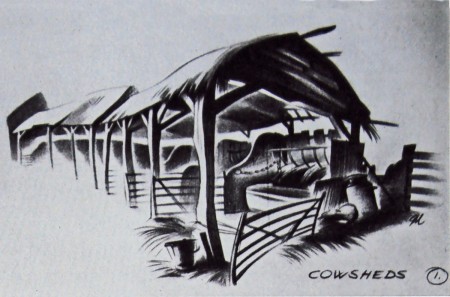

Sketch finalising the type of structure used for housing the cows.

The reader may now begin to understand that the cartoon studio is a closely integrated unit. It is, in fact, an essentially co-operative art. Although each and every person working on the production is an artist in his own right, we are all, to greater or lesser extent, interpreters, each of us contributing towards the achievement of a common idea.

The designer is dependent on a basic idea, and depends yet again on others to finalize his own individual contributions. The designer depends on the background artist; the animator depends on his assistants to refine his rough drawings, and the people who trace and colour his work. No one thing appearing on the screen can truly be claimed as any artist’s sole property, since we all of us have had a hand in it to a greater or lesser degree. The original conception came from George Orwell’s story – we have interpreted his ideas to the best of our several abilities. The final assessment of the studio’s work rests, as always, with the public.

.

Thanks, again, to Chris Rushworth for passing this article on.

I wasn’t even aware of its existence, but find it quite valuable.

.

Books &Commentary &Layout & Design 06 Dec 2011 06:37 am

Setting the Scene – Book Review

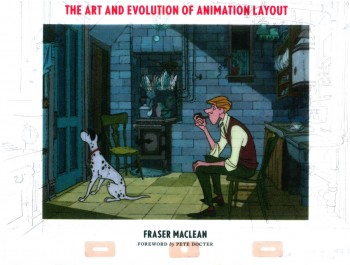

- Setting the Scene: The Art and Evolution of Animation Layout is a beautiful new book by Fraser MacClean. This is a stunningly attractive book with a great number of illustrations going all the way back to Winsor McCay right up to recent Dreamworks films.

- Setting the Scene: The Art and Evolution of Animation Layout is a beautiful new book by Fraser MacClean. This is a stunningly attractive book with a great number of illustrations going all the way back to Winsor McCay right up to recent Dreamworks films.

The book talks about the history of the layout artist and gives plenty of examples from the past to the present, 2D to CG. It addresses how McCay did his films, through the silent animation era, past the Golden Age of animation, right up to the present day’s more complicated methods for computer graphics. It’s a wonderful and heavily researched book with an enormous number of illustrated examples.

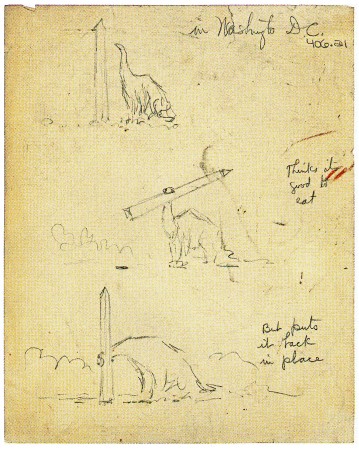

A Winsor McCay LO for Gertie

Original drawn layouts for the likes of One Hundred and One Dalmatians, Chuck Jones/Maurice Noble shorts, Betty Boop shorts, Gulliver’s Travels and The Thief and the Cobbler dress this book giving it a strength that none of the words could offer. Storyboard sequences for Peter Pan, The Rescuers Down Under, Cinderella or Song of the South help get any point across in the most visual way possible.

The book is somewhat dense and took me quite some time to go through it carefully. The material is so interesting, though, that I was ready to give it all the time necessary. Every time you turned a page there’d be another beautiful illustration that just took a lot of time to study.

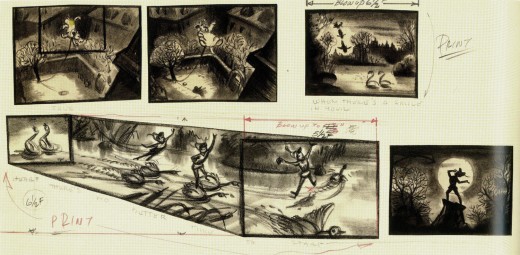

A planning drawing for the great multiplane scene in Pinocchio

from B&W to color

Johnn Didrik Johnsen’s LO for Tom & Jerry “Puppy Tale” (1954)

Probably my only complaint about this book would be that the type is small and harder to read. At times even the illustrations are a bit smaller than I’d like. This, of course, is because anything larger would require greater printing costs and make the book too expensive. So, I’d rather have what sits in my hand than something I’d think hard about buying. As it is, the book is a must own for animation enthusiasts, and there’s a lot to learn for anyone interested in the process of animated film making. I wouldn’t hesitate to wholeheartedly recommend this book to anyone.

Brad Bird’s planning sketch for “The Iron Giant”

I could keep pulling more and more illlustrations from this book. They’re all unique and totally illustrate what the author is talking about at the moment. And they’re all gorgeous. You have to take a look at this book. It’s is another beautiful book from Chronicle Books. They are batting a perfect score, as far as I can see.

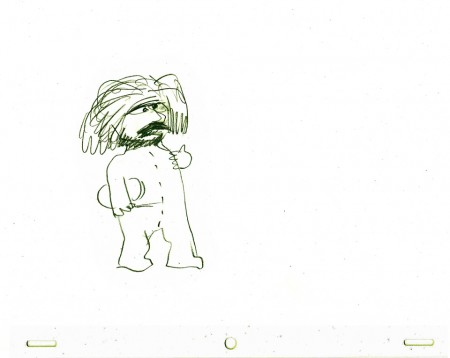

Animation Artifacts &Hubley &Layout & Design &Tissa David 03 Oct 2011 06:53 am

Eggs recap

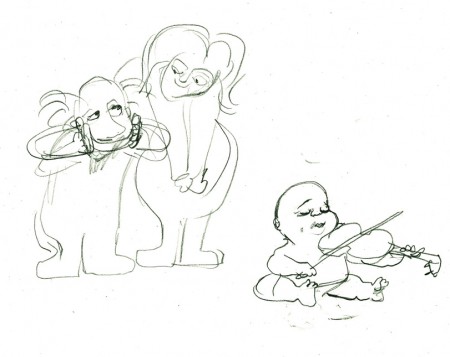

Leading up to the Hubley show next Monday at AMPAS in NY, I’ve said I’ll be posting a lot of Hubley artwork. Today and Wednesday I have a couple of pieces from EGGS.

- I have a lot of artwork from the Hubley short, EGGS, which was wholly animated by Tissa David.

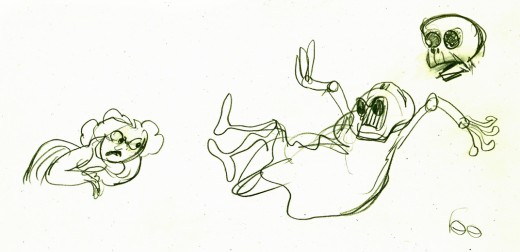

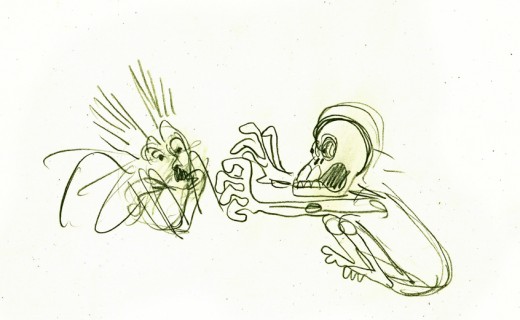

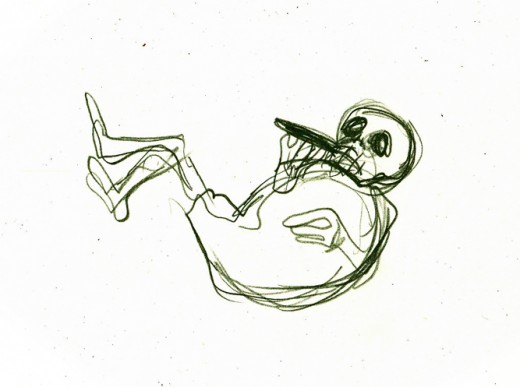

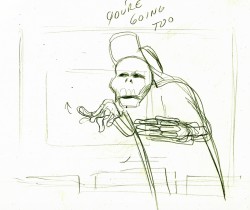

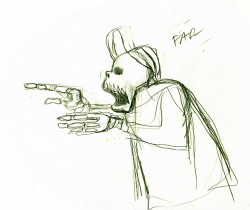

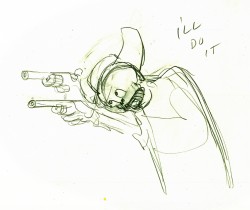

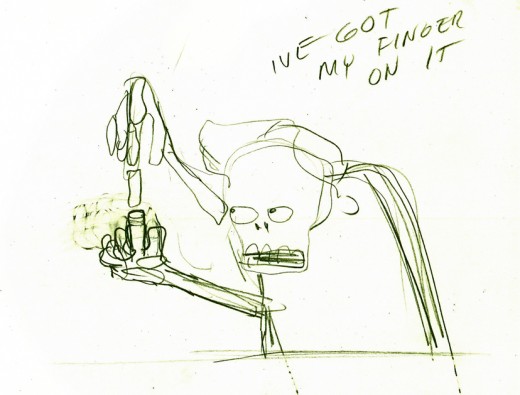

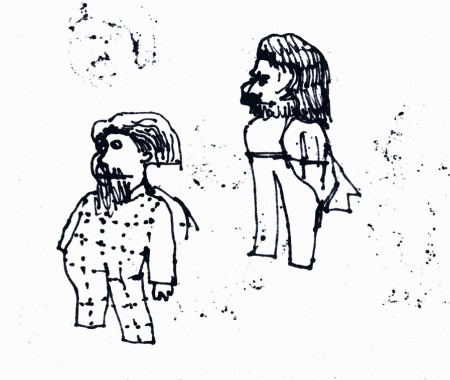

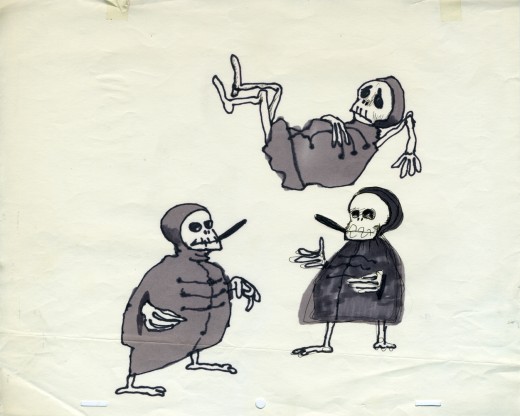

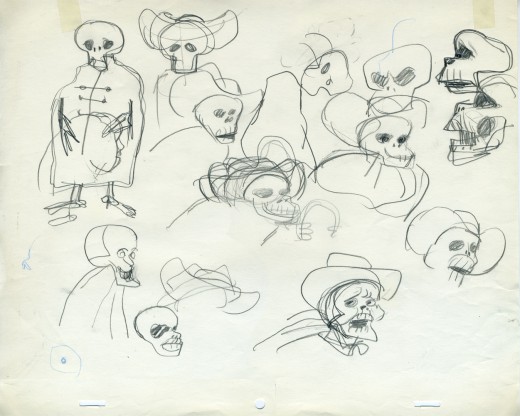

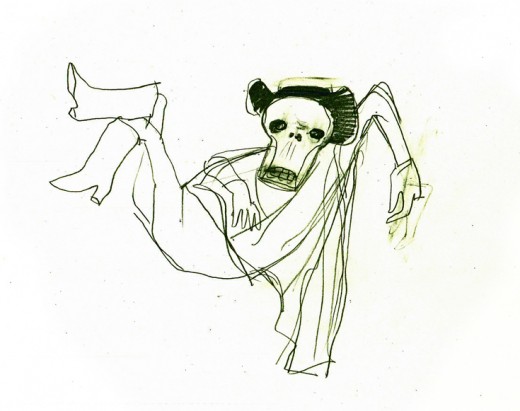

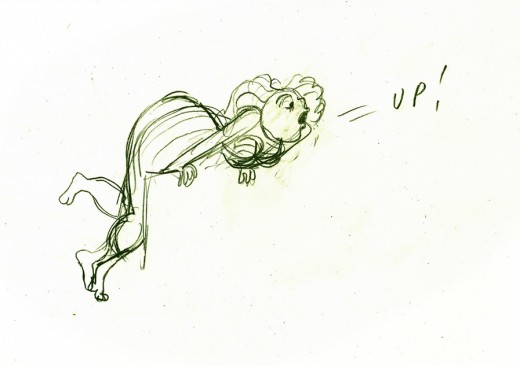

One of the two characters starring in the short is a skeleton, symbolic of death and destruction. The other is a nymph, who represents fertility. The show is basically about the complications overpopulation has presented to the world.

I thought it appropriate for today to post some of the drawings and models for the death character. The images displayed are cropped from the full animation sheets; when you click these displayed it’ll enlarge to the full page. Here they are.

The first model of the character came close to the final.

This is a drawing by John Hubley.

He soon solidified in this model by Hubley.

Tissa David finally worked out some of the problems for herself

and created this working model sheet.

Here’s a beautiful working drawing by Tissa as

she started to pose out the scenes.

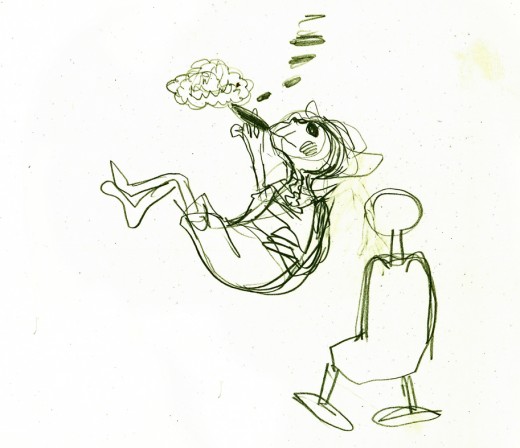

Tissa’s roughs are deceptively simple but convey so much. These drawings

are for her eyes only, usually, she’ll clean it up somewhat for animation.

Unfortunately the dvd is a bit soft partially because of the nature of the

underlit final artwork. Perhaps someday there’ll be a better digital transfer.

Fertility is oozing sexuality in every drawing. This is part of the

same scene as she converses with death about the human race.

Eggs was a short film which was rushed out at a low budget for a PBS show called The Great American Dream Machine, which was produced by designer, Elinor Bunin.

The film follows the political thoughts of John and Faith; they were concerned about overpopulation (there are at least four shorts they made about the subject) and were able to blatantly make a political short for this TV series.

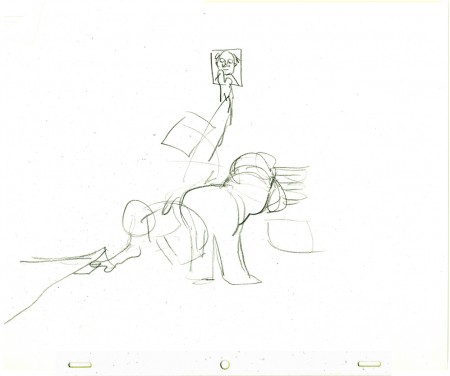

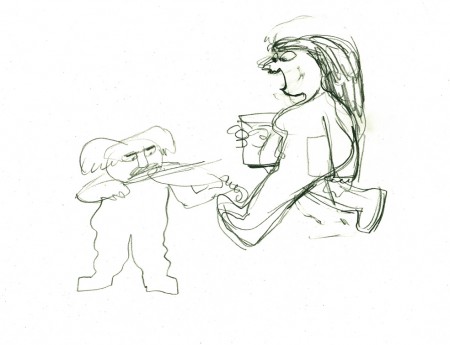

These three drawings are character Layouts by John Hubley.

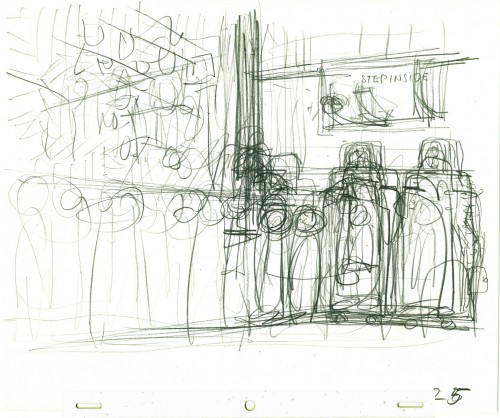

This is a BG Layout John gave Tissa.

This drawing and all the remaining are Tissa David’s drawings.

She would block out her own rough Layout

before jumping in in to animate.

It gave her the chance to thoroughly think out what

little information John had given her. Usually just a

conversation with some very rough sketches.

Here’s a YouTube interview with John & Faith Hubley done in 1973. They discuss Eggs and Voyage to Next.

The video of EGGS starts at 4:50.

Disney &Frame Grabs &Layout & Design &Models 25 Jul 2011 06:53 am

The Old Mill Multiplane

- Having visited the multiplane camera scenes of SNOW WHITE, I can only see the usefulness of going to the keystone of the camera, “The Old Mill.” It’s on this lyrical and beautifully produced short that they admittedly devised the idea of testing the multiplane camera in action. However, in an interview I’ve read with director, Wilfred Jackson, we find that the camera wasn’t available for much of this film. It was being tied up with a number of shots from

- Having visited the multiplane camera scenes of SNOW WHITE, I can only see the usefulness of going to the keystone of the camera, “The Old Mill.” It’s on this lyrical and beautifully produced short that they admittedly devised the idea of testing the multiplane camera in action. However, in an interview I’ve read with director, Wilfred Jackson, we find that the camera wasn’t available for much of this film. It was being tied up with a number of shots from  SNOW WHITE. The interview is by David Johnson posted on American Artist‘s site. Here’s the passage I’d read:

SNOW WHITE. The interview is by David Johnson posted on American Artist‘s site. Here’s the passage I’d read:

- DJ: Since you worked on The Old Mill, you were involved with the multiplane camera. Can you tell me about Garity [the co-inventor] and the invention of this thing and some of the problems and miracles that it did.

WJ: What I can tell you about my experiences with it was the The Old Mill was supposed to be a test of the mutiplane, to see if it worked. Somehow, we were so held up in working on The Old Mill by assignments of animators because Snow White was in work at that time and animators that I should have had were pulled away just before I got to them and other animators were substituted because Snow White got preference on everything. And we got our scenes planned and worked out for the multiplane effects and by that time some of the sequences on Snow White were being photographed. The multiplane camera itself had all kinds of bugs in it that had to be worked out. We were held up until so late that I actually did work on another short – I don’t remember which short. I don’t even remember if I finished it up – did work on some other picture to keep myself busy while we could get facilities to go ahead on The Old Mill. By the time they had got the bugs out of the multiplane camera, they had multiplane scenes for Snow White to shoot and they got it busy on those first. Finally in order to get The Old Mill out the scenes that had been planned for multiplane had to be converted to the flat camera to do the best they could. You won’t find more than a very few multiplane scenes in The Old Mill.

DJ: I wasn’t aware of that.

WJ: I’ve had messed up schedules on pictures but I’ve never had a more messed up one than I can remember for The Old Mill.

So, of course, I’ve searched for scenes that I believe are definitely part of the shoot done on Garity’s vertical Multiplane Camera.

The film is little more than a tone poem of an animated short. It’s about as abstract a film as you’d find coming out the Disney studio in the 30s.

Let’s take a look at some frame grabs from the film, itself:

1

1We open on a slightly-out-of-focus mill with a spider’s web

filling the screen, glistening in focus, in the foreground.

2

2

The camera moves in on the mill and the

spider’s web goes out of focus and fades off.

3

3

Dissolve through to a closer shot as we move in.

4

4

Dissolve through to an even closer shot.

5

5

Foreground objects go out of focus as we move in on the mill.

7

7

Cut to a bird flying in the foreground carrying a worm.

8

8

The interior of the mill, viewed through the window, is dark grey.

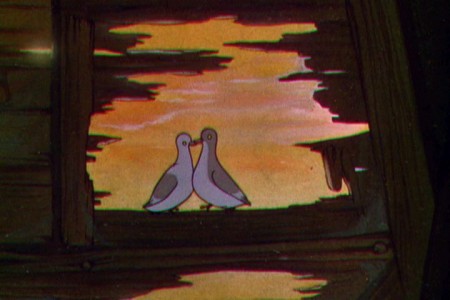

9

9

Dissolve into the next shot which looks as though it appears in the framed window.

Here, we cut to a long pan up the mill using the multiplane. The lighting in this scene is inconsistent. There are flares and glares and some minor jerks to the artwork. No doubt this was done on the multiplane camera, and it would have been reshot if there were time and money.

I couldn’t hook up the artwork to simulate the pan since overlays from one frame didn’t match the next. It was all moving with multiple levels (maybe five?) and they didn’t match from one frame to the next.

1

1The shot starts from the top of the mill looking down on the birds.

2

2

It starts moving up the central column.

6

6

Stopping on a pair of lovebirds.

7

7

The camera continues upward.

At this point there is a cut outside to bats fleeing the Old Mill for the night.

Gustaf Tenggren made some preproduction drawings of this scene which can be found in John Canemaker‘s book, Before the Animation Begins which in itself is something of a tone poem of a book devoted to many of the designers at the Disney studio.

1

1

Now here are frame grabs from the film, itself.

1

1

4

4

The multiplane camera is used only for the exterior shots of the mill

shown over the course of a number of scenes.

5

5

Placed as I’ve done with them, they look as though

they’re one continuous scene over the length of the storm.

21

21

Finally, things settle down and the camera comes to

the Old Mill at rest in the morning.

Animation &Disney &Frame Grabs &Layout & Design 20 Jun 2011 06:56 am

Pinocchio – Multiplane

- In highlighting the use of the multiplane camera in Disney’s animated films, the pinnacle has to be Pinocchio. Two specific scenes jump out in any mention of the multiplane camera: the move in to Gepetto’s workshop and the awakening of the village.

So let’s get right into it:

Sequence director: Ham Luske

Layout by Hugh Hennesy

Animated by “Music Room 2″

1

1Start in the sky with the wishing star that will play

a large part in the film in a couple of moments.

2

2

Circle down from the sky field to an overhead of the village.

3

3

Continue moving down over the rooftops.

5

5

We first see Gepetto’s workshop from a distance.

6

6

There’s a matching cut and we continue to move in.

7

7

The POV of the camera is through Jiminy’s eyes.

8

8

When he moves in, it’s in hops.

10

10

Leaps and bounds as he (through our camera’s eye) gets closer.

12

12

The warm window into the workshop begins to fill the screen.

15

15

. . . looking into the workshop through the window.

16

16

Cut to an interior shot – the interior side of the window.

Jiminy Crickey, with hands and face up to the glass.

Then we move onto a miracle of a shot that would be hard even for computer users. Today, we wouldn’t anchor the feet properly on all those kids walking and running about. It’s an amazing piece of animation history.

The sequence director was Wilfred (“Jaxon”) Jackson.

Layout by Thorington C. “Thor” Putnam.

The animators involved in this scene include: John McManus, Jack Campbell, Cornett Wood, John Reed, Art Babbitt, Milt Kahl, Don Lusk, and Sandy Strother.

1

1The camera starts at the bell tower over the sleeping village.

2

2

Doves fly out as the bell starts to chime.

3

3

The birds fly out of focus as they move forward.

4

4

This allows the camera to start the big move

with the birds covering the tower.

6

6

The camera pushes in to cross the

little footbridge to enter the town.

7

7

The last bird leaves us, and . . .

8

8

. . . we’re into the village.

10

10

We move in toward the cross section of the town . . .

11

11

. . . as people start to come out of their houses.

12

12

The camera moves to the right.

13

13

We move toward a woman with geese as the

camera goes under an overpass.

15

15

We head a few steps down as more

chldren come out running to school.

17

17

The camera continues to the right

seemingly led there by one running boy.

19

19

. . . reaching Gepetto’s house.

20

20

The camera moves in on the house.

21

21

At this time we cut in and the big-time animators take over.

Milt Kahl handles Pinocchio, Art Babbitt does Gepetto, Don Lusk animates Figaro.

Although there are numerous beautiful scenes from Pinocchio that employ the multiplane camera, there’s one last sequence I’d like to concentrate on. This is where J. Worthington Foulfellow (“Fox”) and Gideon the cat cajole Pinocchio into following them so that they can sell him to the puppetmaster, Stromboli. This is a particularly interesting scene for the multiplane camera.

The sequence director was T. Hee.

Layout by Ken O’Connor.

The animators involved in this scene include: Ugo D’Orsi, Jack Campbell, Hugh Fraser, Charles Nichols, Marvin Woodward, Preston Blair, Milt Kahl and Charles Otterstrom and

Phil Duncan.

1

1The multiplane camera scene is several away from this,

but I feel as though this scene really sets up the big one.

2

2

We properly meet the fox and cat as they walk through the town.

3

3

They are well into conversation.

5

5

The fox picks up a cigar stub, telling us about their financial state.

7

7

Several short scenes later, they run into Pinocchio and

coax him away from school to follow them to the theater.

9

9

This cuts into the overhead multiplane shot.

11

11

We watch from overhead with trees and ornaments

marginally blocking our vision of the characters.

13

13

They turn a corner and the camera follows them.

17

17

A quick circling of the tree.

19

19

They do it again, but . . .

20

20

. . . Gideon the cat continues forward moving off screen.

21

21

The fox and Pinocchio continue on the path.

23

23

. . . catching up with them.

24

24

We view them through a tree and the side of a building.

25

25

They go up several steps, but the camera stops.

28

28

. . . the next scene, Jiminy Cricket is running. He’s late trying

to catch up to Pinocchio, thinking he’s on the way to school.

29

29

Jiminy is animated here by Phil Duncan.

David Nethery correctly points out in the comment section,

that Milt Kahl animated this scene.

Animation Artifacts &Illustration &Layout & Design 08 Jun 2011 07:35 am

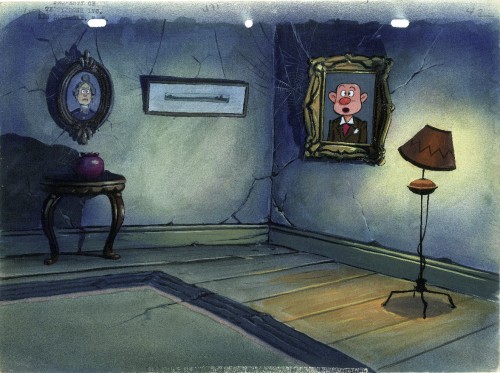

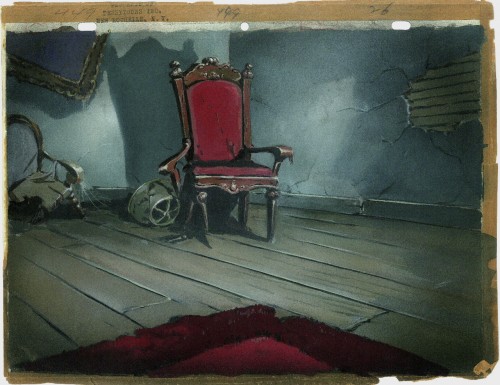

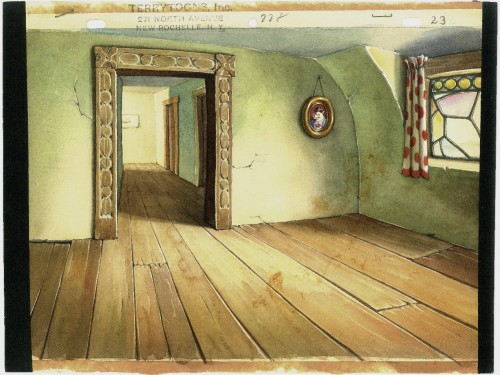

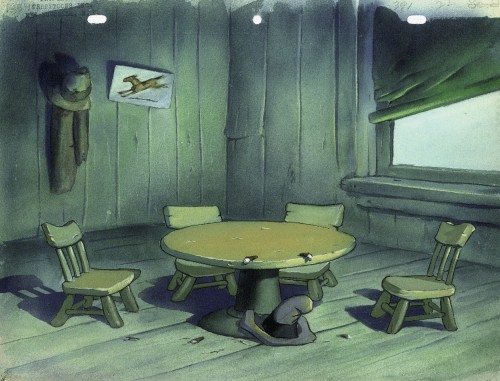

Terry Bgs

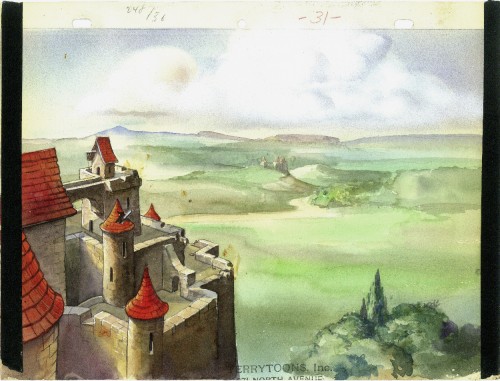

- I have a few Terrytoon Bgs and thought I’d post them today. They come from a number of different shorts from the late ’30s. If you have any idea of titles, please don’t hesitate to leave a note.

I have to say that I really am in awe of the watercolor and/or tempera painting abilities of the artists. They’re quite attractive in person. I must say that they stand up well against some of the other studio work I’ve seen. There were a couple of second rate watercolors done for some MGM Tex Avery shorts I’d seen only yesterday. I wouldn’t expect Terrytoons to be better, but they are.

Enjoy.

1

1

6

6

This Bg is from “The Three Bears” (1939)

Disney &Frame Grabs &Layout & Design 06 Jun 2011 06:40 am

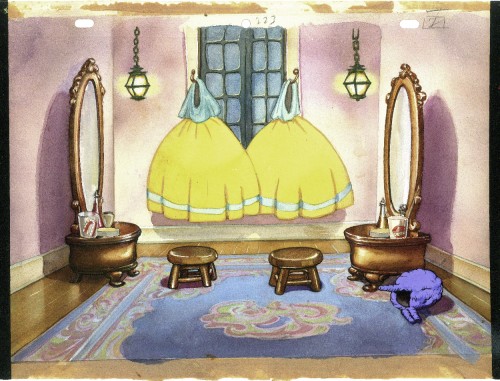

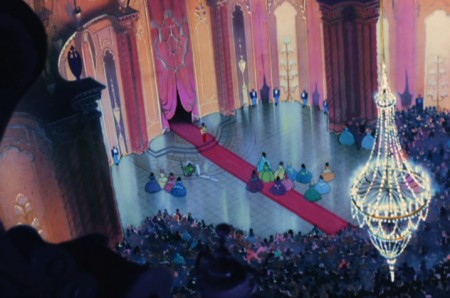

Cinderella Multiplane

- Cinderella was produced on a rather tight budget. After having produced a number of package films, containing collections of shorts, the film was Disney’s attempt to get back into features. His coffers were emptying, and he wanted to get back into the mainstream. They tightened the budget for the film and produced it quickly.

- Cinderella was produced on a rather tight budget. After having produced a number of package films, containing collections of shorts, the film was Disney’s attempt to get back into features. His coffers were emptying, and he wanted to get back into the mainstream. They tightened the budget for the film and produced it quickly.

As such, I was curious to see how many multiplane shots were in the film. I was only able to locate five of them, and they’re all uncomplicated shots – all with a simple camera move in. They didn’t allow for much in the way of focus changes and kept focus pretty mcuh constant throughout them all. There was nothing elaborate built into the camerawork.

1

1

Seq 1.1 Scene 55

This is the opening of the film, after the storybook section reveals the back story.

2

2

The camera slowly begins to move in.

4

4

We’re starting to see some marginal soft-focus in the foreground elements.

5

5

The final setup before the dissolve into Cinderella’s room.

1

1

Seq 2.0 Scene 1

The town with the castle in the distance.

2

2

The camera moves past the town into the castle.

3

3

We end on the castle before dissolving to the interior of the castle.

With this shot we have images of some of the elements used to create the multiplane shot.

The artwork looks to be for a night version of the same shot. I haven’t seen this in the film.

3

3

Level #3 – the castle with sky separate.

1

1

Seq 2.0 Scene 2

The camera moves through the glass. King is out of focus/ glass is in focus.

2

2

As we get closer, king comes into focus and glass out of focus.

1

1

Seq 4.0 Scene not listed on drafts

Cinderella’s coach is on the way to the ball.

2

2

The camera moves in on the Palace.

3

3

The final setup before the dissolve to the next shot.

1

1

Seq 4.0 Scene 1

We move in from an aerial view of the ball – through a window.

Next week I’ll take a look at the multiplane camera in Disney’s feature, Peter Pan.