Category ArchiveArticles on Animation

Action Analysis &Animation Artifacts &Articles on Animation &Disney 09 Jun 2011 07:14 am

Action Analysis – March 15, 1937

- Here is yet more of the Action Analysis class notes transcribed at the Disney studio in this lesson wherein they study clips from several films including a Laurel & Hardy short and a Charlie Chaplin short. If you can get your hands on either (Netflix might have them) it’ll help you to understand the talk.

Participants include: Teacher, Don Graham, animators, Izzy Klein, Joe Magro, either Jacques or Bill Roberts and Stan Quackenbush, storyman Chuck Couch, and BG artist, Dick Anthony.

The complete body of these notes really works as a masterclass in animation for those who are interested and take the time to read them.

Cover

Articles on Animation &Bill Peckmann &UPA 24 May 2011 07:00 am

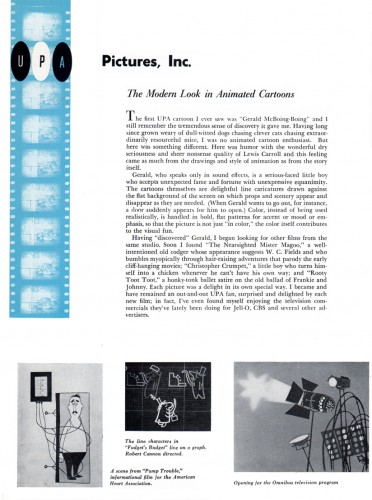

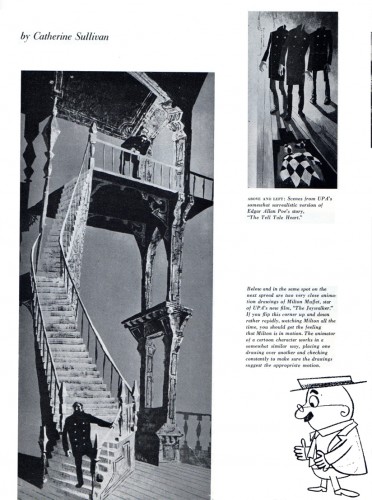

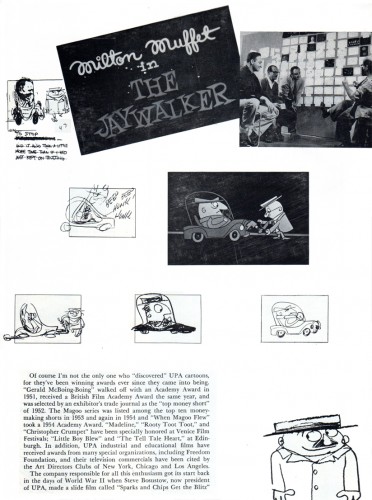

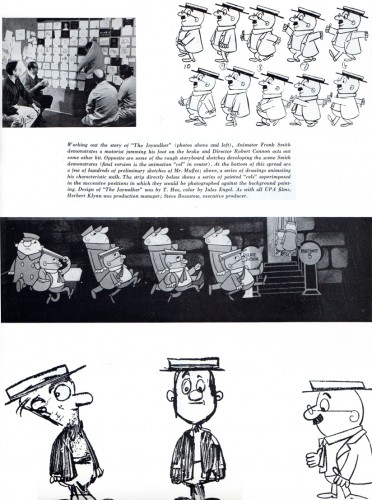

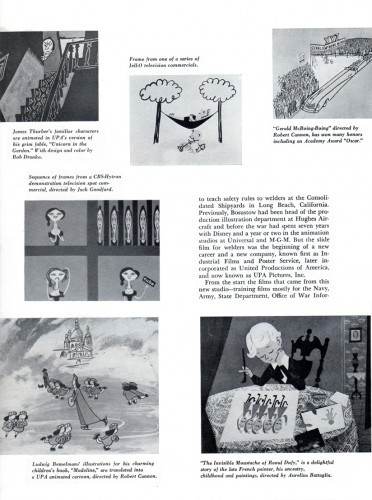

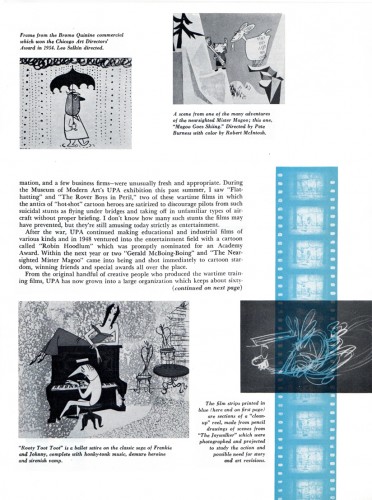

UPA mailer

- Bill Peckmann sent me this in case I hadn’t already posted it. In fact, I’ve never seen it before so it’s a bit of a treasure to me, a big fan of UPA. Here’s Bill’s note:

- This is a studio brochure/mailer* reprinted from American Artist Magazine Nov. 1955. I remember reading the article in high school, it had a huge impact. I remembered it for many years after because of the scarcity of animation articles at that time. And, because it appeared in an “art” magazine, it seemed to make “cartooning” legit.

Did Disney art ever appear in an “art” magazine around this time?

*This brochure was given to me by Ruth Mane (UPA Alumni) many, years ago.

And now, Bill’s passed it onto us. Many thanks, Bill.

1

1(Click any image to enlarge.)

There’s no doubt this article followed up on the Museum of Modern Art‘s 1955 show of UPA art. Amid Amidi posted an extraordinary piece about this show on his Cartoon Modern site. By the way, this is an exquisite site. It’s just a shame that Amid let it lay after his promotion for his book Cartoon Modern. Take some time and browse around that site when you have some time.

A snap of one of the walls at the 1955 MoMA UPA Exhibit.

(from Amid Amidi’s site, Cartoon Modern.)

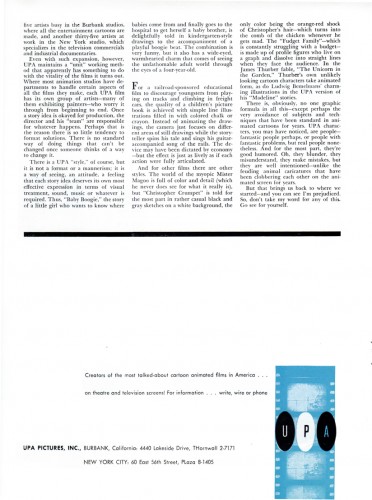

Articles on Animation &Bill Peckmann &Illustration &Rowland B. Wilson 13 May 2011 07:00 am

Rowland B. Wilson – Inspiration

- Leif Peng on his site, Today’s Inspiration, has been posting art of Rowland B. Wilson all this past week. Bill Peckmann has suggested we post a complementary piece today to work with Leif’s site. Consequently, here are a number of pieces. As we go through each, I’ll give you Bill to tell you in his own words what’s coming.

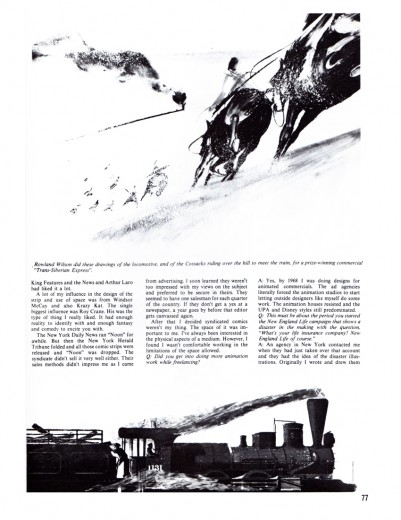

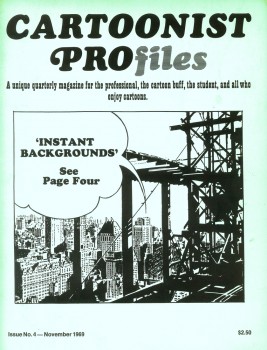

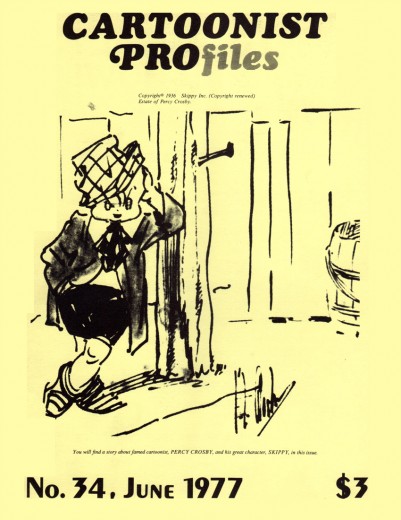

- I’m starting off with a CARTOONIST’S PROFILE of RBW. You’ve posted some of the art in color already, but it’s nice to see how it breaks down in B & W.

Rowland was always totally aware of how his color art would translate into the gray scale.

The cover of Cartoonist Profiles.

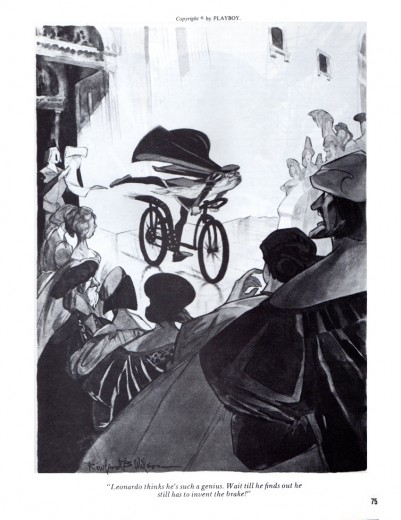

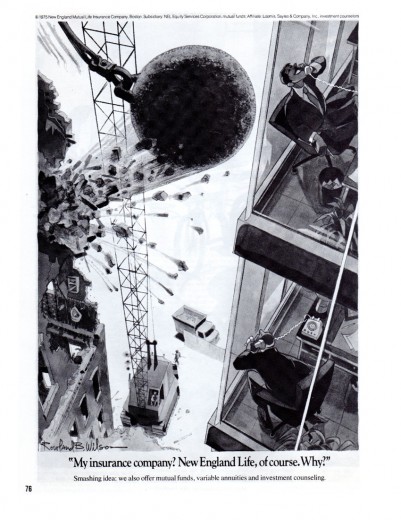

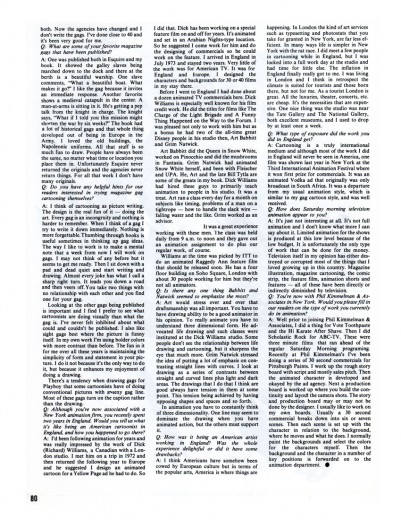

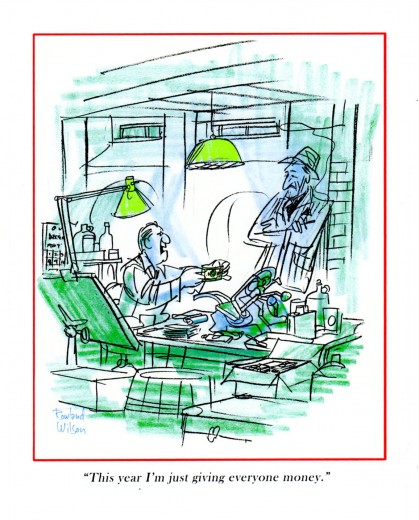

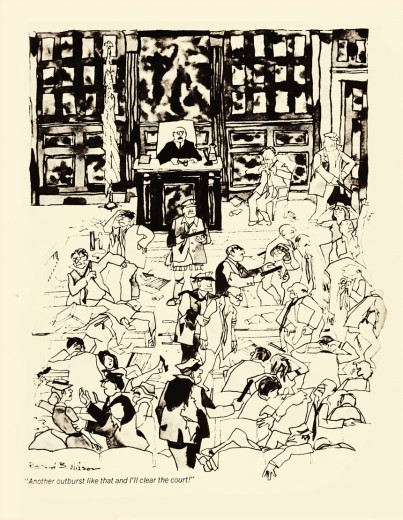

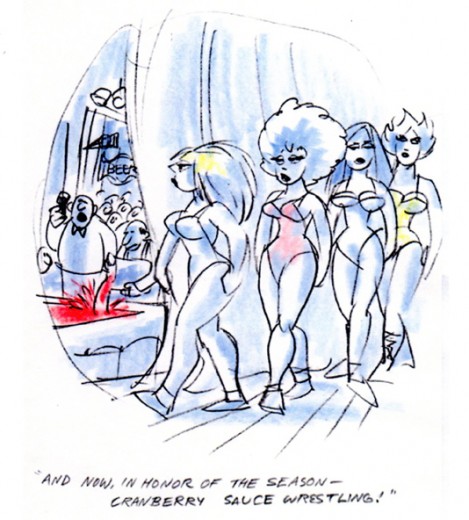

- The next two gags were taken from a reprint book titled “Esquire’s World of Humor”, 1964(?). Fortunately they hadn’t been reprinted in the Whites of Their Eyes, so they are somewhat “new”. Sadly, they were reprinted in B & W, the color art must have been beautiful.

1

1

- Here are examples of how Rowland figured out the shading of his full color TV GUIDE illustrations. He would take a Xeroxed line drawing and then “fool” with it with colored pencils.

1

1

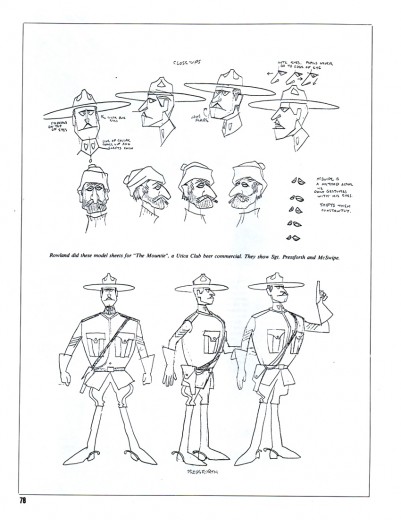

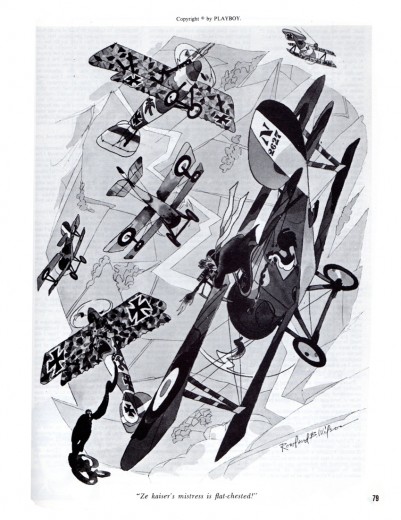

- The next 3 pieces are roughs for PLAYBOY gags. Even his roughs look “finished”. Suzanne Wilson was kind enough to send me these.

1

1

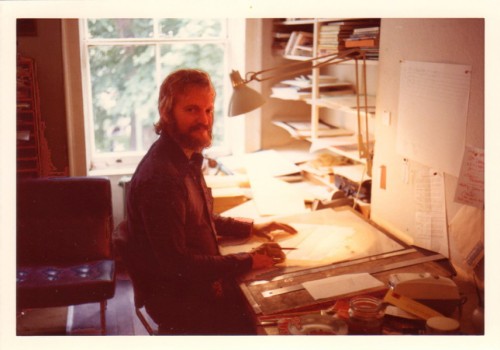

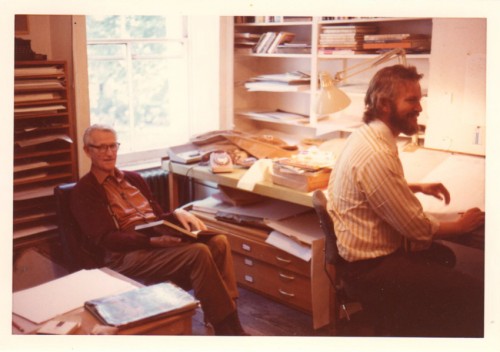

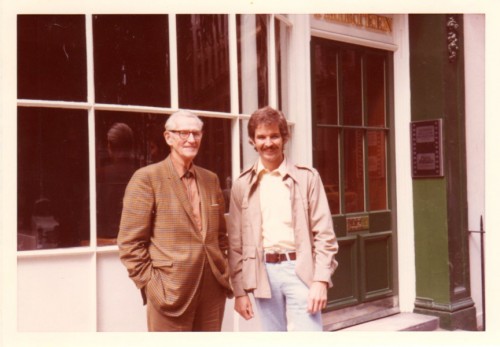

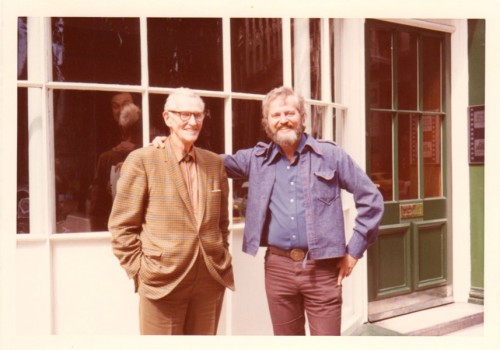

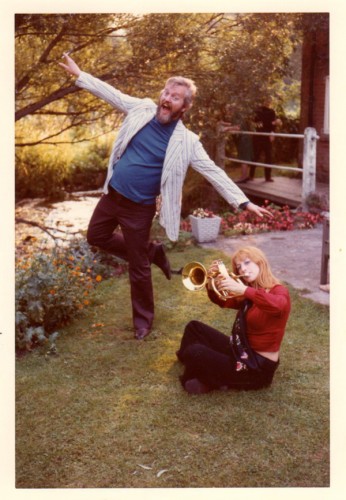

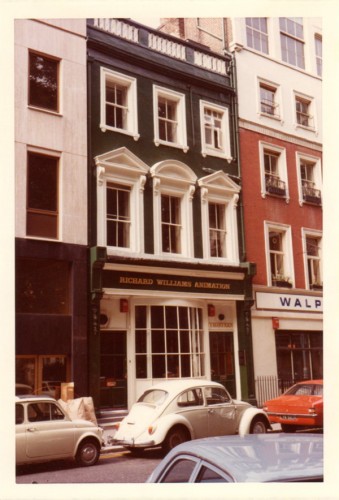

- Here are some photos from June, 1973 when Rowland started working at Richard William’s studio in London. Fortunately for Rowland, that was just the time that Grim Natwick was teaching over there and as they say… that was the start of a beautiful friendship!

1

1One Soho Square

2

2

Animator, Jeff Short with Rowland.

Finally, here’s a note from Suzanne Wilson about the Rowland B. Wilson book which is currently in the works:

- A compendium (?) of Rowland’s personal notes, techniques, sketches, etc. is in the works. It is largely based on Rowland’s collected “how-to” pages that he developed in order to create a system that could be applied to illustration, animation, cartooning and graphic novels.

The publisher is Focal Press. I don’t expect it will come out until 2012…

They haven’t said I can’t announce the book, but the title is not finalized (plus I am having conniptions about ever completing it on time… ![]()

I happened to scroll down on Michael’s website and see Laurel and Hardy. I didn’t know if you knew Rowland painted them on the cabinet doors of a workbench he built…

The workbench

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Articles on Animation &Richard Williams 31 Jan 2011 08:24 am

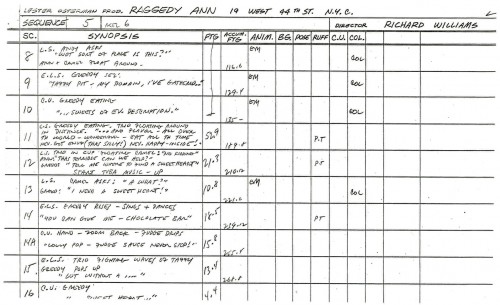

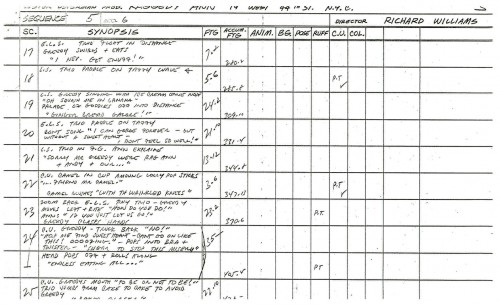

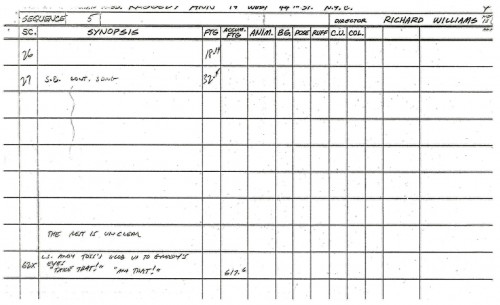

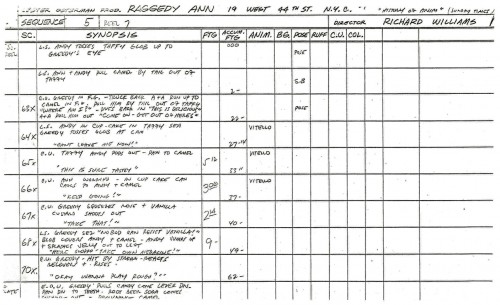

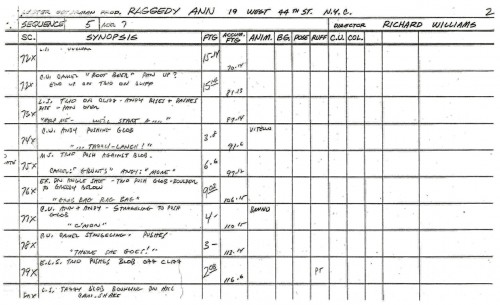

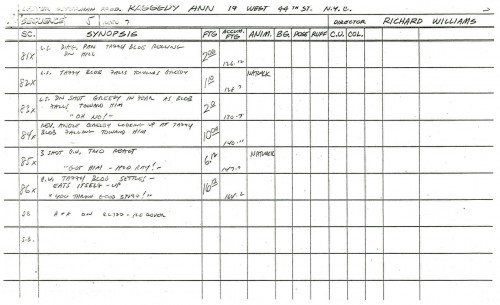

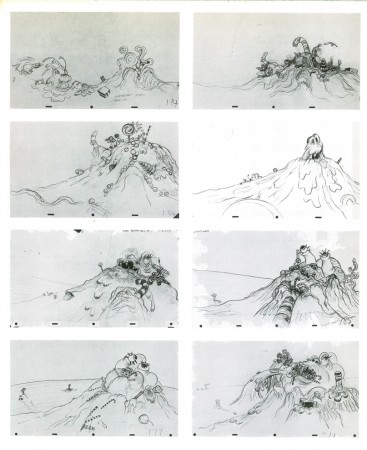

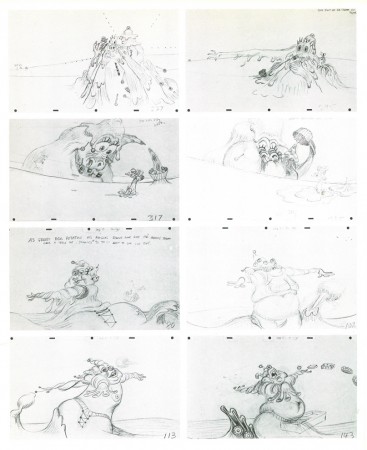

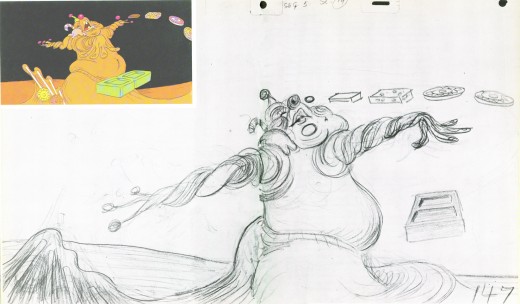

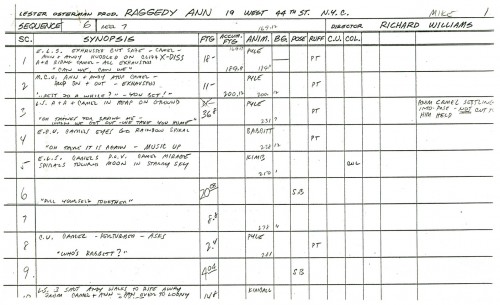

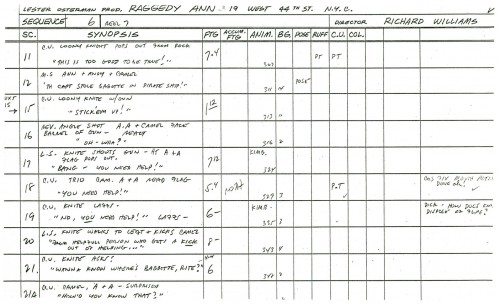

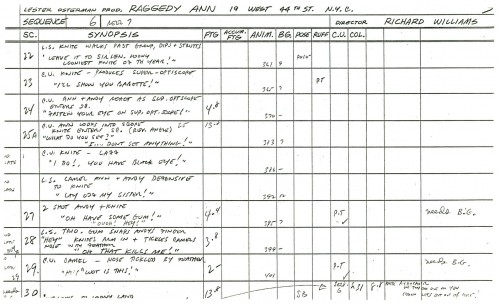

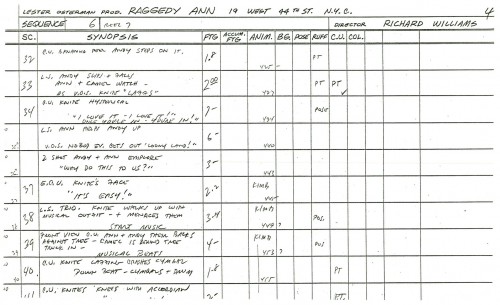

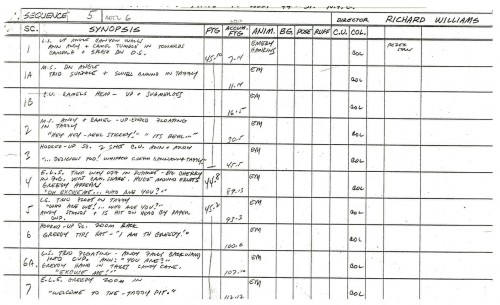

Raggedy Drafts – 4 / seq. 5 & 6

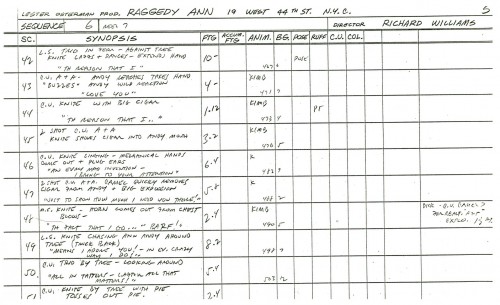

- Continuing the drafts to Raggedy Ann & Andy, I’m posting two sequences today:

5 contains Emery Hawkin’s taffy pit and

6 contains the meeting with the Looney Knight. (This is where the picture really goes off its wheels and takes a deep spin downhill.)

Seq. 5 employs these animators: Emery Hawkins. (A number of scenes were left blank for animator. At the end of the production they pushed this through pulling the sequence from Emery. Assistants became animators, and the animation looked shoddy.) Art Vitello, John Bruno, and Grim Natwick.

Seq. 6 is animated by: Willis Pyle, Art Babbitt, and John Kimball (Ward’s son). Again, several other animators came on at the end: Jim Logan stepped up from assisting to animating the Looney Knight, since Dick felt he was handling it so well.

Sequence 5

1

1

Here are some images from John Canemaker‘s excellent book, The Animated Raggedy Ann & Andy.

Articles on Animation &Illustration 05 Jan 2011 08:30 am

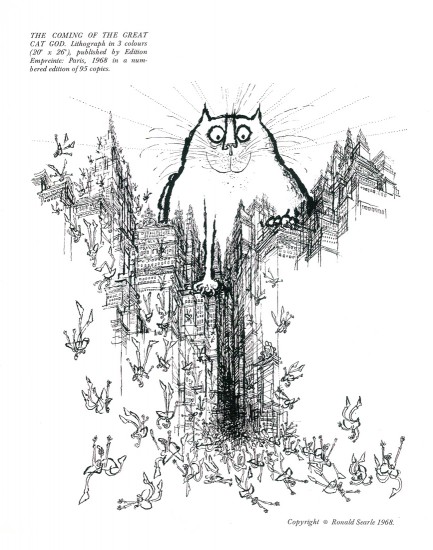

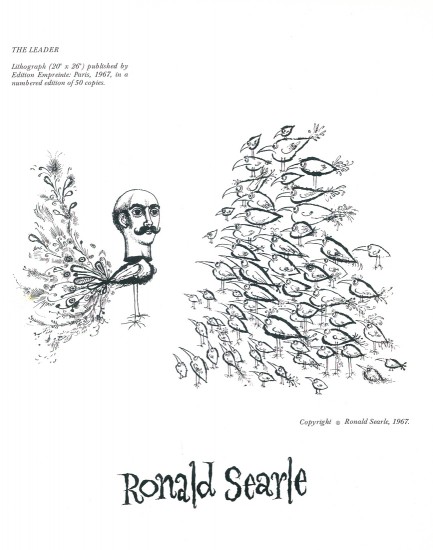

Ronald Searle in Cartoonist Profiles

- Here is an article about Ronald Searle pulled from a copy of Cartoonist Profiles issue #4. It dates back to November 1969.

Writes from

FRANCE

The following article, and the accompanying ‘ideas chart’, were written for CARTOONIST PROfiles by RONALD SEARLE, the noted European cartoonist who makes his headquarters in Paris. He created St. Trin-ian’s, which has become a part of English folklore, has illustrated more than 40 books in the past 23 years, has designed sets and costumes for films, made his own cartoon film John Gilpin’, and constantly does work for American, French and German magazines. One of his publishers describes him as Europe’s most accomplished cartoonist — a macabre black humourist, a lynx-eyed reporter, a gagman of genius, a draughtsman of the stammering line and the delirious arabesque that inimitably characterises his world.

My childhood was unremarkable apart from the fact that I was born and brought up in one of the most beautiful and ancient university towns in England. I drew before I could write legibly (I am left-handed), and I swapped comics in the school yard; no doubt gathering supplementary festering sores in the process. The dog-eared sheets which passed from filthy hand to filthy hand, were hardly recognizable as copies of “Comic Cuts”, “Film Fun” and “Chips ” — the most desirable titles at that time. The more pictures there were to a page and the less text, the happier I was, like all lazy-minded kids. My imagination was almost entirely visual and only faintly literary. However, my great love was books. I devoured everything in our town library, beginning with the infant shelves and graduating at the age of twelve to the adult library. My thirst was insatiable. I frequently took out five books in a day; making my way through A-B: “British Butterflies in Colour”(c. 1894)to Y-Z: “Zjululand, The journal of my encounters in” (c. 1901, I guess). By the time I was 13 I wanted my own library and I began to haunt the secondhand bookstalls and barrows in Cambridge. I earned, begged, and scraped together every penny I could and within five years I had accumulated some 500 volumes for a few pennies apiece. At the outset of my buying, one Saturday, I tumbled onto two or three volumes about caricature, at 6d. each. One of these volumes was Spielmann’s “History of Punch”. I had already decided I would be either an artist or an archeologist and with juvenile confidence I now added the intention of being a “Punch “cartoonist.

That Autumn I enrolled for evening classes in the Cambridge Art School. This had caused some argument between my mother and father for the fee was 7s.6d. a term (about $1.50 then), and we could not afford it. But the money was scraped together somehow. I can guess now that my mother probably put a thicker piece of cardboard in her shoe.

I was obsessed with drawing, and scratched away incessantly. I scrambled through the day at school and my homework afterwards and then rushed off at six in the evening, for three hours of art. By the time I was fourteen I had graduated from the plaster Discobolos into the life class, and painfully shaded my way through several years of floppy-breasted nudes with blue toes and purple legs. It was difficult to keep the fen winds, which blew across the North Sea from Siberia, out of our life-room. Side by side with my art-school work I scribbled comic drawings. The next year, when I was 15, the cartoonist of the local paper left for London and higher things. I stuck a cartoon through the letterbox of the “Cambridge Daily News”, utterly confident that the editor would take it, and that this would solve an important economic problem for me. He did take the cartoon and asked me for more at 10s.6d. a week (about $2.00 then). This represented all the drawing materials I needed, a bit for the family and something over for me.

I continued with those weekly cartoons from 1935 until the war, almost without a break. They were dreadful, but they taught me how to draw for reproduction.

By 1938 the local council had awarded me a full-time art scholarship, and I sweated away for over a year, as a “real, full-time artist”. Lautrec was more precocious, but he was never as happy as I was then. By the time I went into the army, at the outbreak of war in 1939, I had completely saturated myself in anatomy, perspective, history of costume, architecture, life drawing, and all subjects required for passing the Min. of Ed. Drawing Diploma. I missed failure by 2%, but achieved the solid Bolshi-Academic grounding characteristic of Cambridge in the ’30′s.

Also in 1939, I found on a secondhand bookstall, a small monograph by Marcel Ray on the work of George Grosz. It cost me 2s. and changed my artistic direction. I had already established a pedestal for Picasso as the foremost of my living heroes, and I was still grinding my teeth at being unable to raise the $35.00 he was asking then for a pen drawing at a local gallery. Forain I marvelled over, despite his loaded anti-semi-tism, and he had joined the line with Gillray, Rowlandson and Cruikshank, as my self-appointed guardian angels. Daumier’s work was difficult to find, and I had not been able to form an opinion of him then. Goya, however, was one of my gods, and I still day-dream that one day the Prado will drop me a note during a period of stocktaking, to say that they wonder whether I might be interested in accepting a couple of drawings of which they have duplicates.

If anyone influenced me in my work it was on the basis of draughtsmanship, rather than painting. I saw in line then, as I still mainly do now. Above all I admired “Roly’ Rowlandson, with his wit, genius, ability to handle line, ability to range from the broadest and most clownish grotesque to a cunning subversive charm. I cannot say that I have ever consciously had the desire to copy anybody. But if I have been influenced, it is by Rowlandson. And Grosz. Although I had known little about Grosz until I got the Marcel Ray book. I had seen the occasional Munchen album from the ’20′s, and had heard of his flight to America. From time to time I had come across a drawing of his in “Esquire”. But now he fitted into place for me. Grosz exposed the rotting military mind; the filth of war and the stench that lingered after it — and, how he could draw! With this book of his I headed off for my seven years as a soldier.

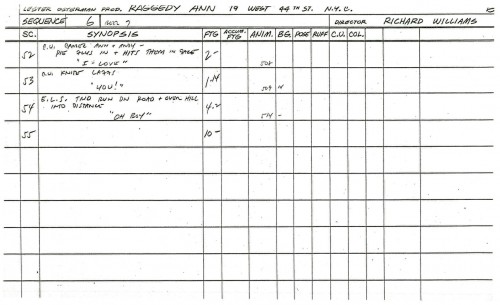

Searle and Monica on location in Rome last year, during the

filming of Paramount’s “Those Daring Young Men in their Jaunty Jalopies”,

for which he designed the animated credits sequence. Searle had previously

designed a similar sequence for the 20th Century Fox film “Those

Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines”. Working with Searle was

the lively young English group “Trick-film”, who made the very successful

“Yellow Submarine”, and with whom Searle is now associated in the

formation of an animation workshop in London.

During those seven years I never stopped drawing. I was a conventional art-student when I went into the army. Before 1939 I had rarely left the town in which I was born. When I came out of a Japanese prison in 1945, after four rough years, I had enough experience of humanity and inhumanity to provide me with a measuring-stick for a considerable part of my life. I also had the facility of seven years of practical application with my drawing. I had documented almost every move I had made, from my first miserable night in the army to the other side of the world and back.

I had been isolated from the world for almost four years; but had also developed in that isolation.

It was then that I was faced with earning my living. I had nothing but fantasies in my head, and a small army pension between me and the post-war wolves at the door while I was getting rehabilitated and thinking about long-term plans for the future. It seemed to me that the only fast and easy way of keeping myself fed was to sell cartoons. So I sold cartoons. This I rapidly discovered needed no particular ability apart from being able to communicate a personal way of looking at things; and apart from having enough nose to smell out the flavour of what was going on and putting it to use. Coming as I did from an atmosphere of stinking cells, wasted bodies and grim humour, my humour was ‘Black’. But so was the post-war climate of rationed England, and my work found a ready market there. I cannot say that I ever thought of cartooning as an ultimate career. All I knew was that I wanted to eat and that I wanted to draw, and this was one way of being able to get some of the disgust I felt for human behavior into print (comically wrapped-up for public consumption). At that point I became a part-time cartoonist. I still am.

Drawing for me has never been a case of therapy because I was shy, or not outstanding in physical activities, or anything else. It was a compulsion. I carried a sketchbook day and night, because I could not stop drawing. To sell a sketch was a pleasure, because it meant a little less economic worry and more freedom to explore. But if I had not sold, I still would not have stopped.

To me line is something which one can explore endlessly, and which keeps me in a constant feeling of excitement and adventure. I know I shall never live long enough to say and do all I want in line. I can only hope to get up each day, bursting to push the exploration a little further. But line is useless if one has nothing to say with it. The artist must be driven with the desire to express something, and use any device to achieve it. He must be perverse. Everybody will want to mould him to their pattern. But in the end he has to satisfy himself — or spend his life trying to please other people.

If satisfaction with one’s work creeps in, the time has come to give up and take to prostitution. A sure sign that there is still hope is when one is miserable at not having met one’s own demands.

The hand is feeble and the artist has still to express with exactitude what his brain conjures up.

Some day it may be possible

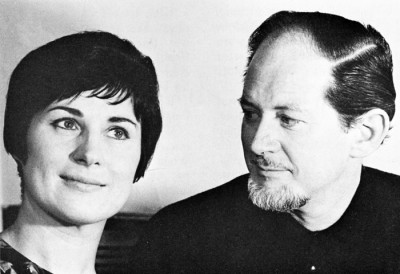

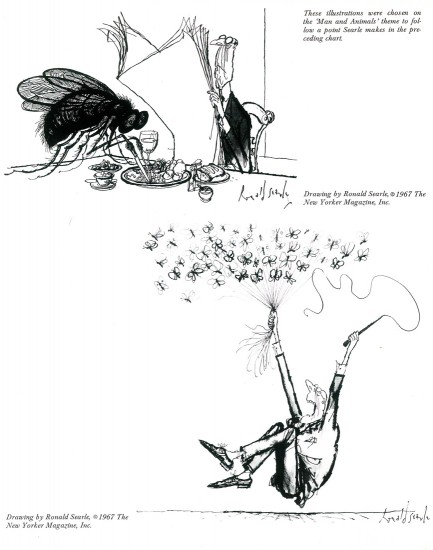

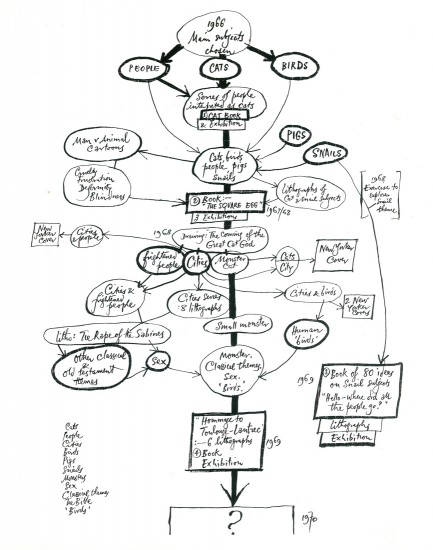

The apple tree on the opposite page was compiled out of curiosity in an attempt to answer the editor’s question: “What routine do you go through to dredge up ideas?”.

It covers the period 1966-1969, and covers the area of ideas only, as opposed to other work made alongside: Book illustration, cinema animation and so on. In 1966, I set out with three main themes as subjects: Cats, Birds, and People. Subsidiary themes, such as Pigs, and Snails crept in soon after. The first four subjects led me to three books, and the Snails led me to a fourth. Lithographs, New Yorker covers and cartoons, and a series of exhibitions developed alongside. As is apparent from the confusion above, I do not attempt to force ideas, but rather to let them drift inconsequentially — and frequently into a dead end. In this case I started out with Cats in 1966, and arrived at Toulouse-Lautrec in 1969. Some drift! I work with no fixed market in mind. Some ideas may best be expressed in lithography, others as large water-colours, others in pen. When they have been sufficiently developed I start worrying about placing them. The outcome of the three years in question was: some 30 large lithographs; 12 New Yorker cartoons and four covers; four books: “Searle’s Cats” (1966/67), “The Square Egg” (1967/68), “Hello – where did all the people go?” (1968/69), and “Hommage to Toulouse-Lautrec” (1969). In addition, 19 exhibitions in galleries in France, Germany, Austria, Sweden, Switzerland and England were arranged for 1966-1970. Here, either the originals or series of lithographs are for sale. Exhibitions are aided by the fact that, to publish books of this sort at an economic price, they need to be captionless and published in simultaneous co-production in England, France, Germany and America. Most of the material in these books has not been previously published — apart from the occasional sale of serial rights. As a working method it is not particularly scientific, or organized. The only factor I watch is: that whatever I do is thought of as an international idea — that it will have equal appeal in any of half-a-dozen countries. Or be equally rejected.

1

1

Articles on Animation &Disney 23 Dec 2010 08:15 am

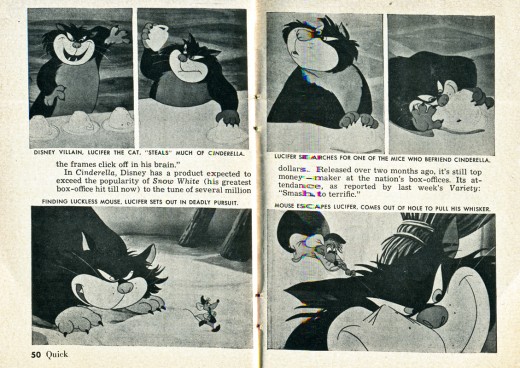

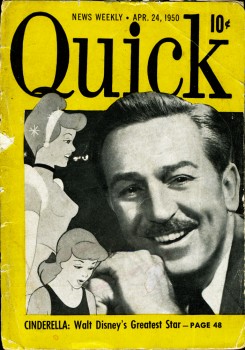

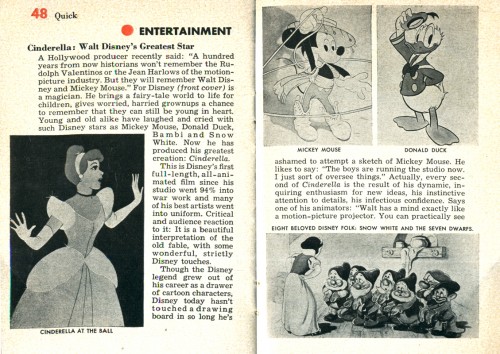

Quick 10¢

- My friend, Tom Hachtman, dropped by with a little gift. Here’s an ancient magazine he’d found called Quick. It’s a “News Weekly” and publishes a lot of strange stories. (One page includes a picture of a woman who’d jumped out of a window and landed on the hood of a car. A bit sensational, for my taste.)

- My friend, Tom Hachtman, dropped by with a little gift. Here’s an ancient magazine he’d found called Quick. It’s a “News Weekly” and publishes a lot of strange stories. (One page includes a picture of a woman who’d jumped out of a window and landed on the hood of a car. A bit sensational, for my taste.)

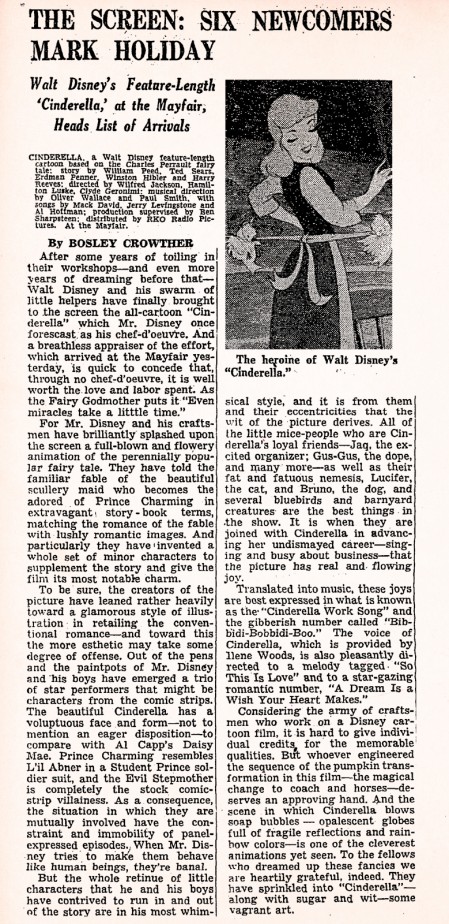

The cover features Walt Disney and Cinderella, which was obviously in its first national release. There’s a nice picture-feature on this film, and naturally I’d like to share.

Curiously enough, the magazine is dated one day after my 4th birthday. The film opened on Feb. 23rd, two months earlier.

The Magazine is printed on poor quality newsprint paper. That means it’s virtually crumbling in my hands. Hence the quality of the photo features isn’t quite up to the Life or Look magazine features you’d have seen in the day. But it does provide some small record.

Here are the four pages, double spread:

1

1

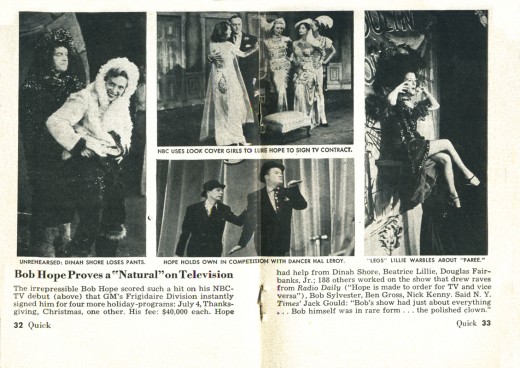

For amusement I’m posting a couple of other pages. Apparently, Bob Hope televised his first TV Special. One of many to come.

3

3

Below, just for amusement’s sake, I’ve added the 1950 review from Boseley Crowther at the NYTimes.

(Click any image to enlarge.)

Articles on Animation &SpornFilms 11 Dec 2010 08:45 am

Sporn-O-Graphics #3

- In 1991, I’d started a small booklet publication, called Sporn-O-Graphics, that I sent out to about a thousand people on my mailing list. Basically, we were promoting ourselves by giving brief interviews and articles about the people in animation who had touched our films in some way. We focused on the films just about to air or were recently completed.

- In 1991, I’d started a small booklet publication, called Sporn-O-Graphics, that I sent out to about a thousand people on my mailing list. Basically, we were promoting ourselves by giving brief interviews and articles about the people in animation who had touched our films in some way. We focused on the films just about to air or were recently completed.

In a lot of ways, it was more fun having a hard copy magazine rather than a blog. It seemed a bit more permanent to have something in your hands, that stayed there until you were done with it.

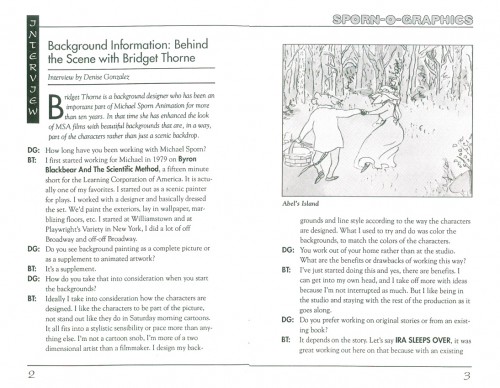

The third issue, July 1992, concentrated on two specific films, NIGHTINGALE and THE POKY LITTLE PUPPY’S FIRST CHRISTMAS. Denise Gonzalez had just taken over editing the magazine and she conducted many of the interviews and articles for the issue. Her interview with art director/designer, Bridget Thorne, was the key piece, for me, in this issue. She also wrote a bit about voice acting for animation, concentrating on Heidi Stallings who had done the principal adult part for THE POKY PUPPY film.

I’ve posted these two pieces, here, to represent that issue.

1

1(Click any image to enlarge.)

Here are links to issue #1 and issue #4

Articles on Animation &Disney &Fleischer 07 Dec 2010 09:19 am

Life after Pearl Harbor

- Today marks the anniversary of the bombing of Pearl Harbor. This was not only a disastrous day for our country, and whatever affects our country affects the animation studios equally.

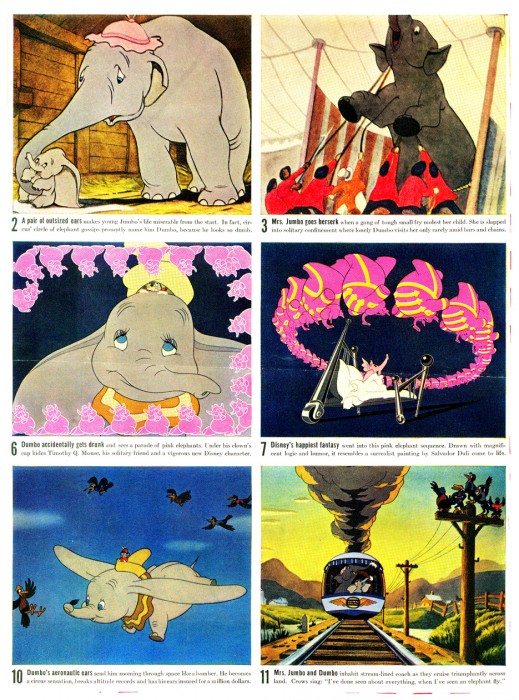

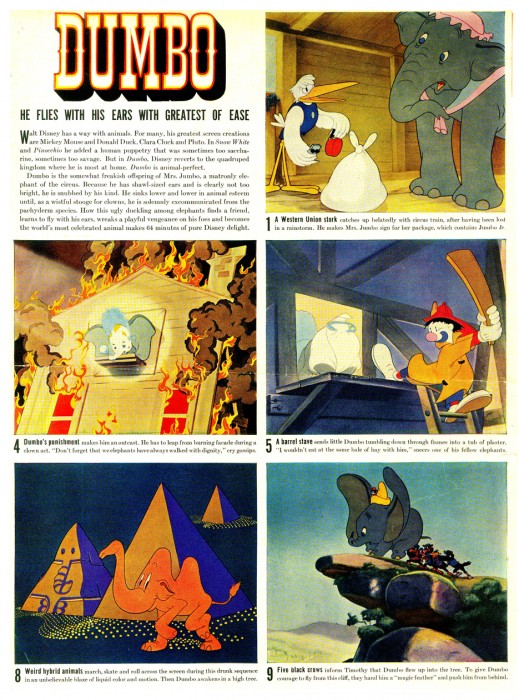

The December 8, 1941 issue of LIFE Magazine included this display of DUMBO stills. A day after the bombing, I kind of suspect no one was into noticing the stills. George MacArthur was on the magazine’s cover – not intentionally bringing War into the issue, but accidentally doing it.

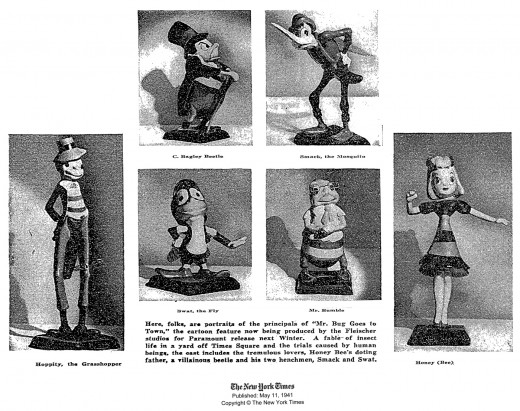

Fleischer’s Hoppity Goes To Town had the same sad problem. It opened the week after Pearl Harbor and sank as quickly as the Hawaiian Fleet. The film was finally reviewed in the NY Times in February 1942 (as can be read below) but there wasn’t much to save it at the box office.

Here’s a promotion that ran in the NYTimes in May of 1941,

six months before the film would be released to a deadened market.

Articles on Animation &Commentary &Daily post &Miyazaki 04 Dec 2010 09:53 am

Grab-bag

- There’s a wonderful new blog post on Darrell Van Citters’ Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol blog. It features the story of Abe Levitow as told by his children, “REMEMBERING THE MOOSE†by Judy, Roberta and Jon Levitow. A great piece to read, I encourage you all to take a look.

- There’s a wonderful new blog post on Darrell Van Citters’ Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol blog. It features the story of Abe Levitow as told by his children, “REMEMBERING THE MOOSE†by Judy, Roberta and Jon Levitow. A great piece to read, I encourage you all to take a look.

This is a great site, by the way. Plenty of material about the artists who were involved in those changeover days at UPA. Great artists get their due, lots of artwork from the film and the period, and lots of info to learn.

- According to Variety, Disney has picked up the distribution rights for the Spanish animated feature, Chico and Rita. This is director/producer, Fernando Trueba‘s first attempt at directing an animated film. Spanish graphic artist, Javier Mariscal, co-directed the film.

- According to Variety, Disney has picked up the distribution rights for the Spanish animated feature, Chico and Rita. This is director/producer, Fernando Trueba‘s first attempt at directing an animated film. Spanish graphic artist, Javier Mariscal, co-directed the film.

The film celebrates the Cuban jazz pianist, Chico, and his relationship with nightclub singer, Rita, as they leave Cuba to move to the jazz world of the New York in the late 40s.

Disney will release Chico and Rita Feb. 25 on more than 100 screens. (This, of course will allow Disney to enter it into next year’s Oscar fest. in an attempt to get the number up to 16 for a five nominee ballot.)

The film won for best feature at the Holland Animation Film Festival in November. The animated movie continues Trueba’s taste for Latin music, already reflected in three awarded musical docus (“Calle 54,” “Blanco y negro” and “The Miracle of Candeal”) and the creation of a Latin jazz record label.

It’s unlikely they’re expecting a wealth of cash from the distribution of the film except, perhaps, making something from the DVD, if it gets good reviews. I notice that they haven’t picked up the TV rights.

– Meanwhile, writer/director, Geoff Marslett’s animated feature, Mars, opened in New York

yesterday. The NYTimes review by Jeannette Catsoulis wasn’t all that it might have been. She called it “. . . low key, low budget and low energy . . .” and pretty much left it at that. The film is another of those rotoscoped-animation type things not quite as energetic as “Waking Life†and “A Scanner Darkly.â€

yesterday. The NYTimes review by Jeannette Catsoulis wasn’t all that it might have been. She called it “. . . low key, low budget and low energy . . .” and pretty much left it at that. The film is another of those rotoscoped-animation type things not quite as energetic as “Waking Life†and “A Scanner Darkly.â€

Marslett, who teaches animation at the University of Texas at Austin. The film is playing at: the reRun Gastropub Theater, 147 Front Street, Dumbo, Brooklyn.

- William Benzon, again, has written several excellent pieces on animated films on the blog New Savannah. He has a two part article on Miyazaki‘s film Porko Rosso. The article intelligently argues the idea of a pig, the leading character, being the only non-human in a particular world where no one takes notice. Part 1 and Part 2.

There’s also a third recent article on thoughts generated by Miyazaki in his book, Starting Point, about how he constructs his films with an ever changing and growing storyboard that doesn’t get done until the film is, usually, already being animated. Go here to read this piece.

- I received a letter, accompanied by a Press Release, from Don Hahn re the video release of his documentary, Waking Sleeping Beauty. Here’s part of the email letterL

- I received a letter, accompanied by a Press Release, from Don Hahn re the video release of his documentary, Waking Sleeping Beauty. Here’s part of the email letterL

- After a yearlong trek though film festivals and art house cinemas, my documentary WAKING SLEEPING BEAUTY is coming out on DVD this week and I hope you’ll get a chance to review it. WSB tracks the renaissance of Disney Animation from box office disappointments and the near closure of the studio, to great success with films like The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast and The Lion King.

The positive response to the film has been bigger than I ever imagined. Not only has it appealed to the fans of animation, it’s also struck a chord with corporations and organizations of all kinds that have gone through their own periods of declines and resurrections. We found that WAKING SLEEPING BEAUTY not only entertained, but touched people emotionally as well.

The DVD has over 80 minutes of bonus material with amazing footage of Howard Ashman working with Jodi Benson during the recording sessions for The Little Mermaid and Howard’s priceless talk to the animation crew about musical theater and animation. I also put together an audio commentary track that features alternate narration from Peter Schneider and myself as well as new unheard material from Glen Keane, Mike Gabriel, Kirk Wise, Rob Minkoff, Jeffrey Katzenberg and Roy Disney.

I hope you’ll get a chance to view the doc and announce to your readers that WAKING SLEEPING BEAUTY is out on DVD tomorrow, November 30th.

I wrote about this film and reviewed it when it was released theatrically back in March of this year. You can read that here.

Articles on Animation 04 Nov 2010 07:11 am

Animation Renaissance

- I enjoy rereading some of the articles in older magazines that talk about the “current state” of animation. We get to see, in hindight, what was thought of the industry during a time of change.

This article from Horizon Magazine, was written by John Canemaker in 1980, some 15 years before Toy Story and the serious explosion of cgi would take place in 1995. Many thanks to John for the article.

Animation. Renaissance ?

From Disney to independents,

animation continues to thrive.

By John Canemaker

Every few years the press alternately declares animation to be enjoying a “renaissance” or predicts the medium’s gloomy future. In the early 1970s, while Ralph Bakshi was riding a crest of popularity with the success of his cartoon features, Fritz the Cat (1972) and Heavy Traffic (1973), animation was rediscovered and pronounced “born again!” Last September, a dozen animators quit the Walt Disney studio and joined Aurora, a film production company started by three former Disney executives. Aurora is spending $7 million to produce a feature-length cartoon of a Newberry Award-winning children’s book by Robert C. O’Brien, Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIHM. Ironically, Mrs. Frisby is a mouse, and, back at the Mouse Factory (as the Disney studio was nicknamed in the 1930s), the premiere of a new cartoon feature, The Fox and the Hound, had to be postponed for six months because of the departure of one-sixth of the animation department. With the recent Disney defections, the pundits (including the New York Times) lamented the “serious gap” in Disney’s creative ranks and noted that the animation industry (and, by implication, the art of animation) had been “long depressed.”

When a dozen animators quit Walt Disney, The Fox

and the Hound, Disney’s twenty-fourth animated feature,

had to be postponed for six months.

Nothing could be further from the truth. Further, the tacit assumption that Disney and the cartoon-film industry represent the

total contemporary animation scene—or even the most important part of it—is a benighted one.

Disney, to be sure, is a great and beloved name, synonymous with animation to the general public; but Disney today is only part of an international art form comprised of a dazzling variety of styles, techniques, and content. Animation continues to thrive and flourish as it has for more than eighty years, not only in industry-run cartoon studios that produce TV series, commercials, specials, and feature-length theatrical films, but in the experimental, personal alternative forms of motion graphics created by the swelling ranks of independent animation-film and -video makers.

Regarding the current Disney situation, it is important to know that it is not an unprecedented event. At least twice before, Disney artists have left the studio en masse — and each time the result was positive for both Disney and the animation industry. In 1928, for example, Walt Disney lost rights to a cartoon character named Oswald the Rabbit; at the same time he suffered the departure of some of his key animators. Oswald was replaced by a new character—Mickey Mouse—and Disney soon enlarged his staff with a corps of artists who, within a decade, advanced character animation to a new plane. Two of the 1928 defectors went on to form the Warner Brothers cartoon studio and, later, the MGM cartoon studio.

In 1941, a large contingent of employees participated in a strike at the Disney studio that crippled production for several weeks.

In 1941, a large contingent of employees participated in a strike at the Disney studio that crippled production for several weeks.

One effect of that walkout was Disney’s eventual diversification into areas other than animation, such as live-action features, nature documentaries, television, Disneyland, and Walt Disney World. The financial security derived from such variegation allows Disney to continue making animated features. Some of the 1941 strikers formed a new studio, United Productions of America (UFA), which revolutionized the design of studio cartoons by moving away from the ultranaturalistic Disney style toward bolder graphics rooted in modern art.

An illustration from_______ Animation production manager Don A. Duckwall revealed that

Le Cuchemar du Fantoche__ despite the recent walkout at Disney, “things are going

a 1908 short by Emile Cohl.__ along beautifully. There is a resurgence of enthusiasm for the

_______________________ product and the future.” Duckwall feels the defection has “cleared the air,” and the studio has promoted peopie who are ‘ ‘taking the responsibility and doing leadership work” on TheFoxandiht Hound feature. So confident is Ron Miller, Disney executive vice-president for creative affairs, that he has scheduled the long-awaited fantasy epic The Black Cauldron as the studio’s next animated-feature project.

“Another benefit of all the publicity about the ones who left,” explains Duck-wall, “is the tremendous number of portfolios being submitted by people wanting to join our animation training program. We now have eight trainees, which is a goodly number for us.” Paula Sigman, assistant archivist at the Walt Disney Archives, confirms the positive effect of the changeover; “Instead of sounding the death knell in the animation department, this has been like a breath of fresh air—to hear the rest of the young guys tell it. There’s a new feeling of unity, of openness and willingness to communicate, of ambition. And although they’re pushed back on Fox and Hound, they’re quite excited.”

Don Bluth, the forty-two-year-old leader and spokesman for the animators who left Disney, said the resignations were “trig- ‘ gered by a dispute over training practices and artistic control.” He plans to make their feature, Mrs. Frisby, in the Disney mode (“It’s the style we love!”), but claims “the content will be different.” Mike Barrier, editor of Funnyworld, a periodical devoted to animation and comic art, has commented that “the real reason the group ! left is not that they want to go beyond what Disney has already done, but because the present studio is not ‘Disney’ enough!”

It is too early to tell if Bluth and company will succeed with their first solo venture and go on to take animated features into areas uncharted by Disney or if the Disney studio itself can succeed with this new creative challenge. The missing factor this time around is, of course, the powerful healing presence of Walt Disney himself; but certainly the competition of the two studios in the area of animated features is a healthy one for animation.

Otto Messmer (second from left) created Felix the Cat

at the Pat Sullivan studio in NY around 1919.

Computers such as Computer Creations “Videocel”

technique are being used today to cut production costs.

The last decade has seen an astonishing increase in the number of animated features produced by studios other than Disney. This trend can be traced back to The Yellow Submarine (1968) directed by George Dunning in London. A still-fresh, pop-art fairy tale of our times, starring the magical Beatles, it is a milestone film that redefined the stylistic and narrative borders of animated features. It also tapped a lucrative nontraditional cartoon-feature market composed of young singles and teenagers as well as attracting the usual family-kiddie audience.

Ralph Bakshi confirmed the existence of this “other” audience with his two aforementioned X-rated cartoons, which, though sloppy structurally, were compel-lingly earthy and poetic. They explored darker, more sensual themes and emotions than Disney dared to. Of a dozen animated features released in the last three years, several aimed toward a wider audience: Watership Down, Lord of the Rings, Allegro Non Troppo, and Dirty Duck. Internationally, there are about twenty animated features currently in production or in the planning stages.

While it can take two to three years to produce a ninety-minute animated feature, the half-hour Saturday morning children’s series on television devour huge amounts of screen footage each week. Abhorred by parent’s groups, but passively tolerated by children, Saturday morning “kidvid”—or “illustrated radio,” as veteran animator-director Chuck Jones terms it—clones on season after season with formula mediocrities such as Casper and the Space Angels, The New Schmoo, Godzilla, Fangface, Scooby’s All Stars, etc.

But in addition to the series, each year brings a number of animated specials to television. With higher per-show budgets and longer preparation time than for series, the specials’ quality level is higher. Look, for example, at the Peanuts specials, The Doonesbury Special, Everybody Rides the Carousel, The Pumpkin Who Couldn ‘t Smile, and The Hobbit, among others. As if this were not enough to keep animators busy, the PBS educational series (Sesame Street, Electric Company, 3-2-1 Contact) solicit brief, informational, animated spots from many studios and individual film makers. TV commercials often use animation when their selling approach delves into the fantastic, as in the surreal Levi’s spots by Robert Abel & Associates and the virtuoso, action-packed Jovan: The Power by Richard Williams Studio.

Today, animation is not just for kiddie cartoons.

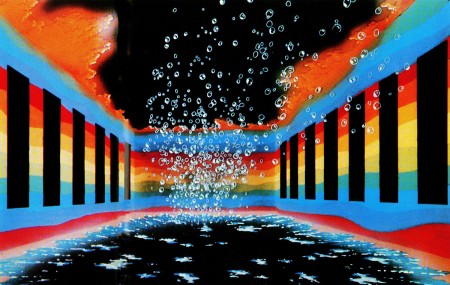

The Oriental Nightfish was a short developed to

be used in the concerts of the rock group, Wings.

The above outlets for animation, theatrical features, and television are dominated by “the industry”—films made by a group of artists and craftspeople in a studio using mostly cartoon designs. It is this work that is most accessible to the general public, both actually and aesthetically. But there is another force working in animation, much less well known but gaining each year in terms of recognition and in avenues of distribution and exhibition. This is a large, vital international network of independent animation-film and -video makers who, freed from profit-motive considerations, explore alternative ways of communicating, interpreting, and expressing themselves and the world through animation. Many work for years on a short film; some subsist on canvas, or a sculptor to clay.

“Because it depends so heavily on technical expertise, we believe the medium of animation enters into the realm of art only when it has a strong personal imprint,” said George Griffin, a leading experimentalist. Griffin, whose inventive films explore the “act of art-making” in a variety of techniques from flip-books to Xeroxed graphics, last year privately published an anthology of new American independent animators.

Titled Frames, the book represents the work of more than seventy animators in this country alone. Their techniques and graphic signatures are lavishly diverse: some artists work in collage (Frank Mouris), others use optical printing (Peter Rose, Anita Thacher), or drawing on film (Steve Segal), direct three-dimensional manipulation (Caroline Leaf, Eli Noyes), rotoscoping (Mary Beams), drawing on paper (Kathy Rose, Dennis Pies), and “cel” animation

(Suzan Pitt, Sally Cruickshank).

To the independents, Griffin notes, “experimental film is not about what a work looks like, but what it does. How it invents its own form, makes its own rules, while stretching the definition of the medium of animation.”

Slowly, the work of these individualistic artists is reaching a larger public. The 1978 New York Film Festival featured a showcase of new animation, as did the USA Dallas Film Festival and the Los Angeles Film Exposition. Independent animators from around the world consistently win top prizes in animation festivals in Zagreb, Yugoslavia, Annecy, France, and Ottawa, Canada. Cable and public television stations book these works, thus introducing them to a wide scope of interested viewers. For two years PBS sponsored the International Animation Film Festival series, which booked many nontraditional animated films. A feature-length compilation, The Fantastic Animation Festival, was distributed theatrically and found particular favor on this country’s college campuses. More and more nontheatrical distributors, who sell and rent films to schools, universities, and library collections, are responding to their patrons’ interest in the new animation and are signing many experimental animators to contracts.

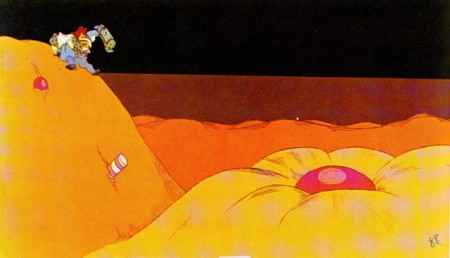

A color model from the pop-art animated feature

The Yellow Submarine (1968) indicated to the

opaquers which colors to use in the final frames.

In the beginning, naturally, all animation was experimental. Although no one knows who first discovered the magic inherent in the camera’s ability to shoot single frames of film, three pioneers defined the animation medium by experimenting and inventing the basic tools still in use today. James Stuart Blackton, a cartoonist-reporter for the New York Evening World, made Humorous Phases of Funny Faces in 1906 and used animation to promote himself and his film company, Vitagraph. The Parisian Emile Cohl made or contributed over 250 animated sequences starting in 1908; his series, The Newly weds, made in America and based on a popular American comic strip, was very influential in identifying the animated-cartoon genre with the weekly comic strip in the public’s mind. Winsor McCay, the most gifted cartoonist-draftsman of his age, tirelessly explored the possibilities of line and motion in his ten films including Little Nemo (1911) and Gertie the Dinosaur (1914)) and promoted animation on his chalk-talk vaudeville tours.

It was in 1914 that American cartoonist John Randolph Bray turned animation into a business. Bray, who might be termed the Henry Ford of animation, organized a staff of specialists doing assembly-line tasks in cartoon studios. He cannily took out patents on certain work- and time-saving inventions (the most important being clear Celluloid acetate sheets called “cels”) which enabled large numbers of films to be produced in series. Thus began the industry of animation, the mass production of cartoon films starring a parade of internationally famous characters. Often the characters came from the newspaper strips, like Mutt and Jeff. But Felix the Cat, created by Otto Messmer at the Pat Sullivan studio in New York circa 1919, was made for the screen —the first creature to express an individuality in drawings that move. Felix’s unique design and, most important, his personality profoundly influenced Walt Disney’s famous animated rodent.

The experimentalists continued to work by themselves creating films that widely diverged from the commercial mainstream. Often the influence of the avant-garde was felt in the studio product, but it was adapted into the “accepted” version —reduced for the conditioned taste of the public who rarely experienced the strong individuality of the original source. (A prime example is the preliminary work the German abstractionist Oskar Fischinger contributed to a sequence in Disney’s Fantasia [1940].) Strong, beautiful, short films of singular vision were made by animators in Europe during the period 1920-1935 and in America in the 1940s and 1950s. Among these animators were Len Lye who painted directly onto film, Lotte Reiniger who used cut-out silhouettes, Alexander Alexeiff who worked in pinscreen, John Whitney with his computer works, and Jordon Belson whose specialty was video projects.

Interest in animated films has been enhanced by a wave of printed supporting material: in the last five years, scores of periodical articles and eighteen books on all aspects of animation have been published. Some of the books deal with cartoon nostalgia (The Fleischer Story), some focus on technology and technique (Visual Scripting), others on a particular genre (Puppet Animation in the Cinema), or historical perspective (Experimental Animation: An Illustrated Anthology). Six new books in the works aim toward publication within two years.

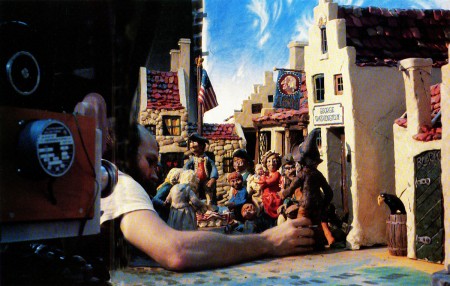

Oscar-winning Will Vinton, one of today’s innovative animators,

adjusts characters from Rip Van Winkle, a half-hour clay animation.

The current issue of the American Film Institute’s Guide to College Courses in Film and Television shows that more than sixty major American colleges feature animation workshops and/or film-tape appreciation courses in their curriculum. Most celebrated is the California Institute of the Arts, which divides its animation work-shops into an experimental group under veteran designer Jules Engel and a character-animation section headed by Disney shorts-director Jack Hanna. Many of En-gel’s students have become some of today’s most exciting independent animators and several of Hanna’s students have found their ways to jobs at Disney or other cartoon studios.

The cross-pollination of ideas gained by the proximity of the two Cal Arts animation courses is a good omen and symbol for the future of animation. The art today is undeniably vigorous and varied; computers are being developed to enhance productivity and cut production costs (such as Computer Creation’s “VideoCel” technique). The growing visual sophistication of audiences and the international exchange of ideas between the avant-garde and the industry, the new technology outlets for films and tapes, such as video-disks and home-tape consoles, make the future of animation exciting and unlimited.

- Who’s Watching Cartoons?

Most viewers are children, but there is a healthy contingent of adults, particularly for reruns of old theatrical shorts.

Tim Roberts, head of creative services at New York’s Channel 5, notes that his station receives a “steady number of phone calls from adult viewers” inquiring as to the titles of the shorts shown in the daily series. “Some people want to see a certain favorite, like Bugs Bunny or Woody Woodpecker, but most of the callers have videotape machines and want to tape certain films to add to their cartoon collections.”

Last November Channel 5 presented a half-hour Cartoon Film Festival for one week in prime time (8 P.M.), with interesting viewer results. Diane Sass, vice-president of marketing and research at Channel 5, consulted the Arbitron report, a book of TV viewer demographics and noted that the festival received a ten rating, which she said is “very good. The usual programming in that time slot is a game show, ‘Crosswits,’ which usually pulls a six to seven rating.” More interesting was the breakdown of viewers according to age. The Cartoon Festival, said Sass, “had a total viewing audience of 1,217,000. Of that 438,000 were kids, 225,000 were teenagers—age twelve to seventeen—and the majority of viewers, 554,000, were adults, eighteen-plus.”

A guest fellow at Yale University teaching animation history, John Canemaker is the author of The Animated Raggedy Ann & Andy—An Intimate Look at the Art of Animation: Its History, Techniques and Artists and makes animated films and documentaries about animation.