Category ArchiveArticles on Animation

Articles on Animation 10 Apr 2010 07:48 am

Animation in the USSR

The following is an article ripped from the pages of ANIMAFILM #1, 1979. This is definitely dated since the walls fell, the Recession hit and none of these companies exist anymore. However, it’s always good to cover a snapshot of history.

Animated film is a welcome guest everywhere. It fills people with joy and expectations. It is a cathartic and rejuvenating agent. Its magic holds people of all ages spellbound. The Home Committee for the Art of Animation, meeting in a plenary session in Kishinev, has deliberated upon Soviet animated film-making as an international art. Prominent Soviet artists, who have laid down the foundations for domestic animated film production, animators of international repute as well as young newcomers to the art, have thoroughly and seriously discussed the further possibilities for developing animated film.

Animated film is a welcome guest everywhere. It fills people with joy and expectations. It is a cathartic and rejuvenating agent. Its magic holds people of all ages spellbound. The Home Committee for the Art of Animation, meeting in a plenary session in Kishinev, has deliberated upon Soviet animated film-making as an international art. Prominent Soviet artists, who have laid down the foundations for domestic animated film production, animators of international repute as well as young newcomers to the art, have thoroughly and seriously discussed the further possibilities for developing animated film.

Gaydar’s little boy an Rudyard Kipling’s Mowgli, Charles Perrault’s

Cinderella and Little Red Riding

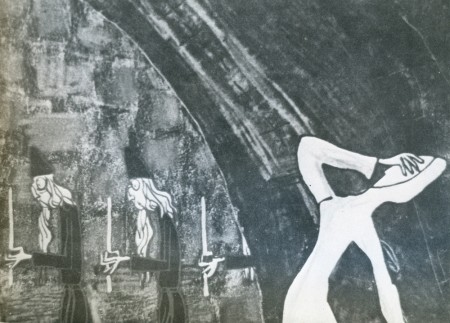

The Sauna, by Sergei Jutkievich, Anatoli Karanovich ____Hood, Alexei Tolstoy’s Buratino,

_______________________________________________and Ilya Muromets – the protagonist of the “hillins” (fables). Pushkin’s Duke Gwidon and the czar’s daughter-turned-swan by magic, Yershov’s Hunchbacked Pony, or Samuel Marshak’s and Korney Chukovsky’s enchanted animals – are the dearest friends from our childhood days. Animator’s hands and imagination have breathed new life into literary characters, making them available to young audience even before they can write and read. Actually, such encounters are for young viewers their first ineffaceable lesson in beauty, as well as a school of character because the stories deal with friendship, valiancc, goodness and justice. This is what the tremendous, inimitable value of animated film consists in. “Animated films cannot be compared to anything else”, said the great Soviet animator. F. Khitruk. at the Kishinev session.

Two-thirds of the animated film production in the Soviet is addressed to children. But adults value animated films equally highly. Its form makes this branch of art an ideal go-between linking adults and children. It is characterized by a variety of subjects, and a richness of styles, genres and ideas. The animated film industry is now developing in every Soviet republic.

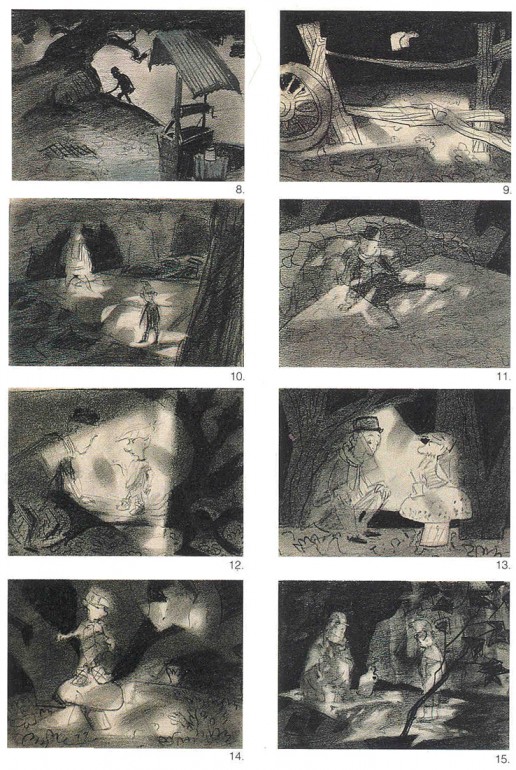

Film, film, film, by Fedor Khitruk

The production of twenty-two republican film studios was reviewed in Kishinev. The Chairman of the Home Committee for Animation, B. Stepantsev, who holds the title of the Merited Artist of the Russian Socialist Soviet Republic, pointed to the very important fact that young film makers in Georgia, Kazakhstan, the Ukraine and Estonia have become widely known for their courageous study of current customs, morals and philosophical problems. This group of artists derives inspiration from native folklore and everyday events. Another notable group is the animators from Moldavia who are busy searching for unconventional forms of artistic expression.

The Kishinev session has shown thai the Soviet art of animation is expanding vigorously. (ATEM)

The distribution of short animated films, as other films not quite fitting the established standards of distribution, encounters problems. However, over the past 10 years the Soviet’s movie industry and distribution workers, cooperating closely with civic organizations and animated films popular both with children and adults.

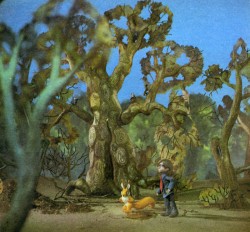

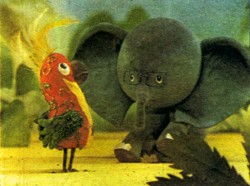

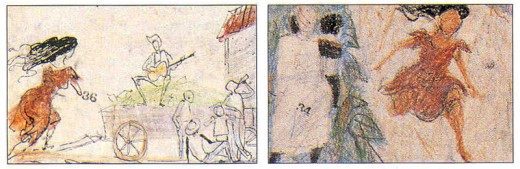

(Left) Farewell, Green Forest, by Michai! Kamenetski

(Right) One While Horse, by Vladimir Danilovich

The Soviet animated film studios annually turn out about 80 short films for children of different ages, not counting the films commissioned by various organizations, and didactic and advertising films. Every year the Soviet distribution network channels to viewers about 60 new animated films made in the USSR and about 20 such films made in socialist countries. On top of this the movie theatres have at their disposal about 500 archival films. Altogether, they avail themselves of a repertory of over 600 animated films, and that number is on a steady rise. Between 600 and 1000 copies of every film are made, some of them being reproduced on 16-mm tape for screening in schools and by travelling movie theatres.

.

There are various forms of film distribution, the most popular of them being feature-length package programmes. Sometimes such programmes exceed the standard length when a feature film is preceded by several, rather than one, short animated films. All in all, the package programmes are categorized into those addressed to children and (hose addressed to adults. Children’s programmes are mostly shown in special children’s cinemas (of which there are 300 at present) and during morning film sessions in standard cinemas on Sundays and holidays.

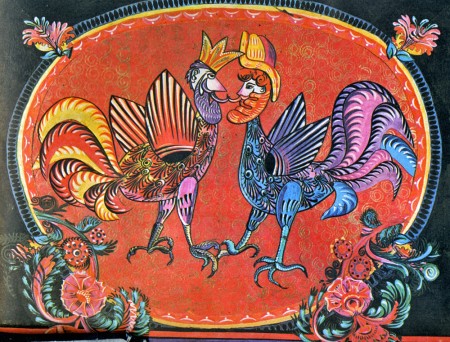

Gilt on Their Foreheads, by Nikolai Sercbrakov

Animated films tor adults chiefly accompany evening feature length film sessions or are shown in special short-films-only cinemas, of which there are over 200.

There also are four cinemas in Moscow which are exclusively used lo show animated films. Their combined capacity is 1.200 seats.

The methods of popularizing animated films are multifarious. For example, there are animated-film lovers’ societies attached to movie theatres attended by both adults and children.

The societies organize film shows to which they invite both domestic and foreign film animators and directors. Soviet audiences have already met with such animated film celebrities as Todor Dinov, Popescu-Gopo, Paul Grimault, Nedelko Dragic, Otto Koky, Stefan Janik and many others. Regular displays of works by the animators from the “Soyuzmultfilm” studio, and of children’s drawings, are held in cinema foyers. Every year animated film theatres have a turnout of 1,500 000 viewers.

The Spear, by Rein Raamat

Soviet film-makers lake an active part in popularizing the animated film art. The most effective means they employ are the folk festivals organized in the individual republics, regions and districts with the help of the USSR Film-makers’ Association and film distributors. The festivals provide abroad forum for presenting the top achievements of Soviet animated film in cities, towns, and villages. The events are widely advertised and covered by the local press, radio and television networks. Special documentaries on the films shown, stories about the film-makers and interviews with the participants are regular items attendant on the festivals. The “Soyuzmultfilm” studio has already organized folk festivals in Western and Eastern Siberia, in the Caucasus and northern regions, the Far East and Central Asia. Artists from the “Kievnautchnyifilm” (educational film studio), which has an animation branch, take part in the festivals held in Ukraine. Also film-makers from Estonia keep in close touch with audiences. The folk festival in Moldavia marking the 40th anniversary of “Soyuzmultfilm” was a resounding success. Over 120 meetings between animators and audiences took place in the republic’s capital, Kishinev. Undeniably, the folk festivals stir popular interest in animated-film production and enlarge the scope of its influence.

The publishing house of the V/O “Soyuzingormkino” enterprise regularly brings out advertising and informative material on animated films meant for local film distrihutors and advertising and information centres.

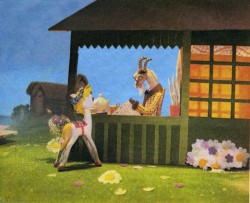

(Left) Where Is Baby Elephant Going, by Ivan Ufimccv

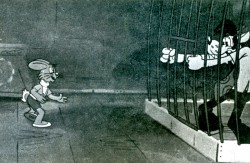

(right) Wait a Bit, by Vyacheslav Kotenochkin

Animated films are regular fixtures in central and regional television broadcasts. Every month the television networks in the Ukaraine and Georgia sponsor special broadcasts entitled the “Animated Films Panorama” and introduced hy the well-known animated film directors, Yevgeny Sivokon and Vachtag Bahtadze.

N. Venzher

This article gives me the opportunity of repeating a short anecdote on this blog.

It was 1977, and I was working at Raggedy Ann & Andy for Richard Williams. I was the head of Assistant Animators and Inbetweeners. A friend of mine who worked for an agency that supervised tours of Russian artists around the US, gave me a phone call. He was in NY with a pair of Russian animators who couldn’t speak a word of English, and he promised them that he’d try to get them into a NY animation studio. Could I do this on a Saturday?

I asked Richard Williams, and he said ABSOLUTELY NOT! (He was so violently against it, I could almost imagine that he’d had a bad experience in the past.) I called Faith Hubley (John was in England at the time working on Watership Down.) She and the studio were unavailable. The best I could do was to contact Howard Beckerman – in the same building as Raggedy Ann.

Howard had a one-man studio in NY, and had two small rooms and a couple of cubicles with lots of cel paint bottles coloring the space.

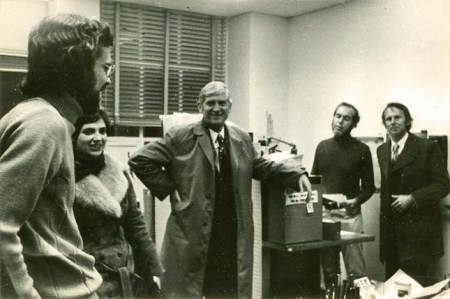

The two animators, who I met for the first time, were Rein Raamat and Vyacheslav Kotenochkin. I spoke poor to little Russian, with my friend, Richard Mayer, interpreting most of the conversation. We had a nice talk in their hotel room, went for a light breakfast and visited Howard, who was incredibly gracious and kind.

(L to R) Richard Mayer, Maxine Fisher, Vyacheslav Kotenochkin,

Howard Beckerman and Rein Raamat

Afterward, I offered to take them wherever they wanted to go in the City. I had my car.

Vyacheslav Kotenochkin wanted to go to “Yablokov Street”. I didn’t need a translator to figure out that that meant “Apple” street. I did need help to realize that he meant “Orchard” Street. “Yablokov” was the name of a storeowner on the street. I took them down to lower Manhattan to go shopping at these turn-of-the century type shops. Kotenochkin bought a dozen pair of jeans for his friends and a bunch of other things including a multi-colored clown-like wig. Rein Raamat just enjoyed watching.

When we were back midtown, Vyacheslav Kotenochkin left us for his hotel, and Rein Raamat wanted to see a Modigliani painting in the Museum of Modern Art. That was his favorite artist, at the time, and he’d never seen one in person. This part was easy. I was a member and got him in for free. When we turned the corner and this great big nude by Modigliani appeared Raamat gasped. A tear came into his eye, and the day was sunk in my memory as a key one.

For years after that, Rein Raamat exchanged letters and books. I’d sent him a large book on Modigliani and he sent me a German book on Bosch. We were able to write to each other in Russian. He didn’t speak it well, at the time, neither did I. Two people writing and reading pigeon-Russian seemed appropriate as a way of communicating.

Unfortunately, we haven’t spoken, nor have we written in a number of years. Though we have infrequently met up at some film festivals. Life’s like that some times.

See this post, to view some photos of the day.

Animation &Articles on Animation &Independent Animation &Puppet Animation 06 Apr 2010 06:15 am

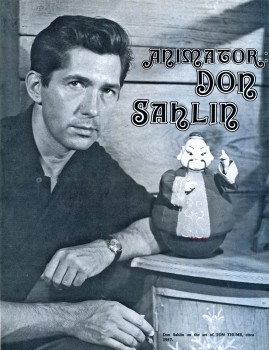

Don Sahlin

- After posting some stills from Ray Harryhausen’s Golden Voyage of Sinbad, I decided to look back and see if there were any other material I could post about 3D model animation.

I came upon this interview with Don Sahlin in Closeup Magazine, no. 2. published in 1976 by David Prestone.

(Bio)

Born in Stratford, Connecticut, Don Sahlin (say—lien) was introduced to the world of marionettes at age eleven, when he saw a production of HANS BRINKER AND THE SILVER SKATES by the New York Marionette Guild.

Born in Stratford, Connecticut, Don Sahlin (say—lien) was introduced to the world of marionettes at age eleven, when he saw a production of HANS BRINKER AND THE SILVER SKATES by the New York Marionette Guild..

Joining the PUPPETEERS OF AMERICA organization, he was soon inundating many of that group’s members with letters of inquiry as to the correct method of constructing and performing marionette shows. This correspondence brought Don an offer from Rufus Rose (who, several years later, was to create all of the figures for the HOWDY DOODY televison show) to spend several weekends with Rose and his wife as an apprentice.

.

In 1946, Don started another apprenticeship of many years standing when he began working with Martin and August Stevens, who performed sophisticated marionette dramas of subjects like Macbeth, Joan of Arc, and Cleopatra.

.

A stint of Summer Stock in Rhode Island followed, when Don felt he would try his hand at the acting profession, but he soon became disenchanted with this form of theater work. In 1949, Don traveled to Hollywood, where he worked with puppeteerist Bob Baker, doing party shows for many of the movie stars there.

.

Don then returned home to perform a show of his own designing, SAINT GEORGE AND THE DRAGON, which played around the Connecticut area. Later jobs involved working with very large puppets accompanied by a symphonic orchestra, Chinese shadow plays, and, in 1950, a marionette version of the LAND OF OZ stories that Burr Tilstrom was preparing as a television pilot. Working for a year on this project, Don was then drafted into the army.

CLOSEUP: How did you first get involved with stop-motion animation?

.

DON SAHLIN: When I got out of the Army in 1953, I had heard that Michael Myerberg was looking for puppeteers to work on HANSEL & GRET-EL. For some reason, he thought that puppeteers would make better animators than (stop-motion) animators! I was interviewed and got the job. I had to then go through a three-week training period with Myerberg in order to better acclimate myself with stop-motion. It was a very bizarre setup.

DON SAHLIN: When I got out of the Army in 1953, I had heard that Michael Myerberg was looking for puppeteers to work on HANSEL & GRET-EL. For some reason, he thought that puppeteers would make better animators than (stop-motion) animators! I was interviewed and got the job. I had to then go through a three-week training period with Myerberg in order to better acclimate myself with stop-motion. It was a very bizarre setup..

CU: Do you recall who sculpted the puppets?

.

DS: A man by the name of Jim Summers did the sculpturing. As I recall, they had a special machine shop where all the armatures were constructed. I’d give anything to own one of those armatures now. They were pieces of art.

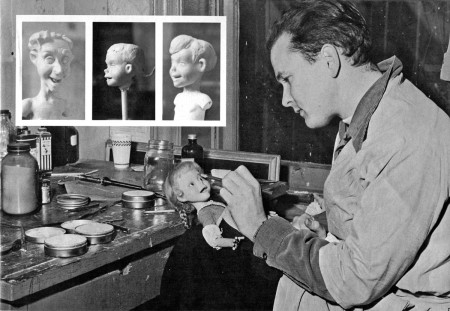

James Summers applies makeup to an almost finished Gretel.

Inset: Clay heads by Summers.

Below: Evil Witch Rosina Rubylips views herself

as portrayed in a preproduction sketch.

.

CU: Were they all ball-socket in construction?

DS: They were, but you’d press levers, which was really interesting. If you wanted to move the thigh, for instance, you’d press a little lever near the thigh area which would release it for a tiny movement. Removing pressure from the lever would freeze the puppet in position. As you may know, they were all held on the stage with electromagnets.

CU: Could you elaborate on how that was done? It’s interesting that Myerberg used that method of support as opposed to the tie-downs used by today’s animators. . .

DS: The base of the stage was all metal, and they had these strong electromagnets underneath. The puppets really clomped down on them. Of course, we’d have to break the electromagnetic field in order to move the legs to their next position. One night, as I remember, we were working on a very hard scene. Myerberg had a twenty-four-hour shift there, and the animation varied so greatly because people would come in and start animating where the day-shift had left off! We went out to dinner, and somehow, somebody had hooked the electromagnets into the main power source. Naturally, we killed all the lights as we went out. As we pulled the switch, we heard a series of plops. All the puppets had fallen over! We had to start the whole thing all over again! I quit twice on that film … I never got screen credit, because I quit before it ended.

CU: Here’s a quote from the book Puppet Animation in the Cinema: “The Kinemins used in HANSEL & GRETEL . . . were controlled by the use of electrical solenoids, and electromagnets in the feet. . . a system which is a closely-guarded trade secret…”

DS: (Laugh) That’s a lot of bunk, you know. The only thing “electronic” was the electromagnetic setup that held the puppets on the stage. Myerberg had a big panel upstairs where he’d use close-up heads that were wired to this big, blinking board. You’d turn knobs, but there was nothing electronic involved. There was simply a wire inside the mouth, and with a twist of a certain knob, the mouth would go “that way,” and so on. But it was all manual. Anything else that was said was a big put-on.

CU: A similar incident occurred with the publicity on Ray Harryhausen’s 7TH VOYAGE OF SIN-BAD, where the reporters of the media were quot-iny the producer on how the skeleton fight was “electronically” controlled . . .

DS: Nothing but press stuff, I would imagine. I’m glad you mentioned Harryhausen. God, I love his work. The one I saw recently again that I just adore was JASON AND THE ARGONAUTS. His work was absolutely superb. Classical mythology is such a wonderful area to explore. Why don’t they do more things like that?

CU: We’ve been asking ourselves the same question !

DS: Those skeletons were frightening! You know, I’ve learned to enjoy animation more now because I’ve been away from it for so long. But it’s a curious thing. Do you remember Trnka’s A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM? I saw it again and fell asleep through most of the whole thing! I was just so aware of how long it took to do each scene that it fatigued me … But it was a beautiful film.

CU: Getting back to HANSEL & GRETEL. Who actually did the camerawork on it?

DS: That was a very strange thing. Myerberg hired Martin Munkasci to photograph the animation. He was one of the great still photographers and had done a lot of things with Garbo and so on. Oddly enough, Myerberg felt that since stop-motion was nothing but a series of still frames, a capable still photographer would be more appropriate to do the camerawork. It was a very strange rationale on his part. Martin knew virtually nothing about motion pictures. Fortunately, a very fine Acme camera was used which was simple to operate, and he would just line up the shots and photograph. Anyhow, we went nuts, going up and down opening and closing those trapdoors all night long, sitting under that stage! And those sets were gigantic. Many of the backdrops were paintings, but a lot of it was also dimensional.

CU: We know that Myerberg isn’t with us anymore. What became of his organization after HANSEL & GRETEL?

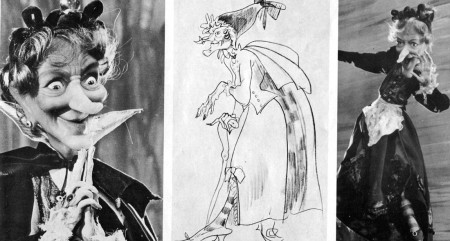

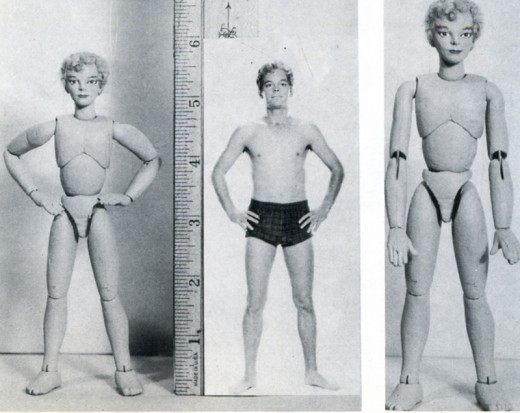

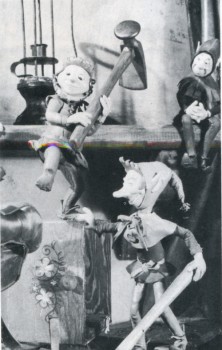

Above: The beginnings of the KINEMINS . . .

incomplete sculptures of Hansel and his father .

Below: Several puppet figures and a set (which predate all work

on HANSEL AND GRETEL) from ALADDIN AND THE WONDERFUL LAMP.

All sets and puppets for this project were put aside

once work began on the Humperdink musical.

.

DS: Myerberg had all sorts of aspirations to do other things, but they never materialized. I think his sons own the film now.

CU: Where did you go from there?

DS: After I left Myerberg, I was in association with Kermit Love, who had also worked on the film. We were going to do a full-length motion picture Of Beatrix Potter’s TAILOR OF GLOUCESTER. It’s a charming story about a tailor and a Whole community of mice. We were going to animate all of the mice. We had the whole thing set up in London . . . Robert Donat was signed to play the lead role and Margaret Rutherford was also cast for the film. We began building the mice and we had some funding, although we hadn’t gotten to the point where we were able to build them all. Suddenly, we had a bad partnership and the whole project collapsed.

CU: Would the animated mice have been combined with live actors in the same scene?

DS: No, they would have been separate. I don’t really like it when they combine things, although Ray Harryhausen is a master at it. I wouldn’t want to do it in that way, but I respect what he does very much. Anyhow, I returned to the States when our TAILOR OF GLOUCESTER failed, and then got 3 call to go out and do work on TOM THUMB. That film, I think, was the most enjoyable thing I worked on during this period, because it was my first big job in Hollywood.

CU: How did you get involved with George Pal?

DS: At the time, 1 had been out in California working with a puppeteer friend of mine named Bob Baker. When TOM THUMB began, I was asked to build a little six-inch stop-motion marionette of Tom that they were going to use in the long shots. It was a funny thing. They said that he had to wear a fig leaf, so I carved this puppet with ball and socket joints, and he really looked naked. George was in England shooting in 1957, and decided that he wanted the puppet for a particular scene. But all my work was in vain, because the fig leaf that Tom wore covered almost his entire body. I had thought that the fig leaf would be in scale with his body, but that’s not the way it turned out. I think Wah Chang has the little Tom Thumb figure now, but I would love to own it. It was really an exquisite little puppet. It was all carved out of walnut, and I filled the legs with lead to make them heavy. It was never used in the closer shots, just distance stuff.

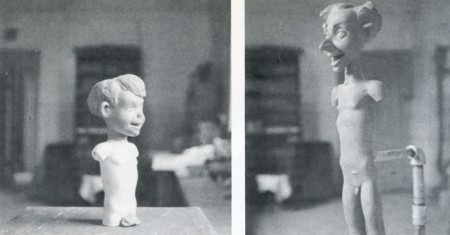

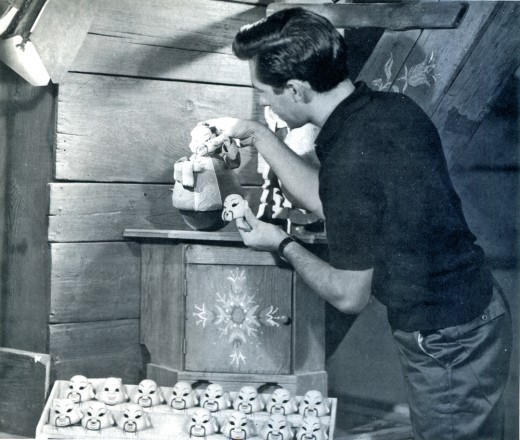

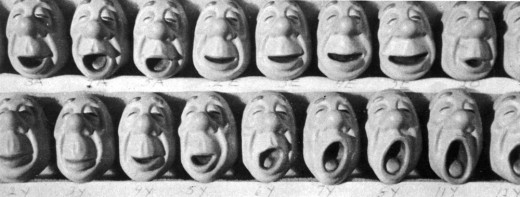

Two photos illustrating the replacement method of animation, utilized on TOM THUMB.

Instead of achieving changes of expression through manipulation of a stop-motion model’s

facial features, a series of heads are prodced, each head having a slightly different

expression on it. Changes are made by simply substituting one head for another.

Above: Don Sahlin placing a head on Con-fu-shun, and

Below: Numbered heads created for The Yawning Man animated by Gene Warren.

.

CU: How did you get to be a part of Project Unlimited?

DS: After I had carved the little stop-motion marionette, they started filming all of the animation sequences, but 1 had to go back to New York. Then Bob Baker called me from California and told me that they needed an animator. I talked to Wah Chang, I think it was, and he said, “Come on out and work for us!” 1 worked out at Project until about 1962. They wanted me to stay on, but Burr Tillstrom of Kukla, Fran and Ollie fame wanted me to come back to New York to work with him on a Broadway show. And it’s funny how fate is. I didn’t want to go; I really loved working at the studio, especially after THE TIME MACHINE. Anyhow, I did go to work for Burr on this small, cabaret-type show at the old Astor Hotel, but it soon folded. And like I say, 1 regretted leaving Hollywood, but I also met Jim Henson of the Muppets here in Mew York, and it led to probably my most successful period.

CU: Could you tell us just what you animated on TOM THUMB?

DS: I animated Con-fu-shun, a lot of the little guys that just popped up, and the Jack-in-the-Box. Gene Warren and I did all of the animation, just the two of us. Gene is a marvelous animator; he did the Yawning Man sequence. I spoke to Gene a little over a year ago, and I was so happy to find out that he does my favorite commercials—Chuck-wagon! To me, the most charming commercials ever done!

CU: What were some of the techniques used in animating Con-fu-shun?

DS: I remember Con-fu-shun was a very simple puppet. The armature was bolted to the stage and he just rocked. Occasionally, I think he got off for a couple of drop shots. The facial expressions were accomplished by replacing just the faces, which were made out of wax. We had a whole tray of all his faces. We’d just put on “E1″ or “E2,” or “Smile 1,” “Smile 2.” I know his eyes were not connected to the face; they were always independent. The faces just slipped on in perfect registration. I remember the little eye-pick I used for animating his eyes; it looked like a little hypodermic needle.

The TOM THUMB marionette created by Don Sahlin and used only in long shots.

CU: Did you have anything to do with constructing the large prop furniture, or giant hands and horse’s ears, that Russ Tamblyn was to interact with?

DS: No, that was all done at MGM, in England. Project Unlimited was a kind of neat little studio by itself, completely independent. Pal would do all of his stuff at MGM, but I wasn’t involved in the work done there, even on THE TIME MACHINE.

CU: You did some work on DINOSAURUS. Could you talk a bit about it? We know that,the models were built by Marcel Delgado, but little is known about who actually did what as far as the animation goes . . .

DS: I animated the Tyrannosaurus and the fight scenes that were involved with it. The rest of the animation was done by myself and Tom Holland; he got to do most of the Brontosaurus, the less ferocious of the creatures. I remember the night we finished the scene where the Brontosaurus died in the quicksand. The material used for quicksand was Fuller’s earth; I guess it’s used because it looks in scale. We had a kind of screw-jack that the puppet got on, and we kept pulling it down slowly in stop-motion, beneath the surface of the quicksand. When we finished the scene, we were exhausted. Then we asked ourselves, “Should we leave him in or take him out,” this great piece of sponge rubber? So we pulled him out again and we were hosing him off and cleaning him up. It was funny!

I also remember the night the big dinosaur fight took place. They were playing Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring in the background and boy, it really inspired us to animate! We got through that fast, where they were tearing and ripping at each other.

CU: Is Tom Holland still animating in Hollywood?

DS: I don’t know what Tom is doing now. It’s interesting; Tom wasn’t really an animator. He was an actor, primarily, and he somehow got involved in animation. We did all of those scenes together. I recall another amusing incident on DINOSAURUS. Do you remember those close-up shots of the manually-operated dinosaurs that we intercut? We once spent a whole day boiling ochra and straining it to make it look like saliva was really dripping from their mouths. It was just hideous!

CU: DINOSAURUS is an interesting thing to look at as an animation film, but technically, it did seem to be somewhat under par in comparison with some of the others. . .

DS: It was a very cheap film. A lot of the rear projection work was just awful, especially the scene at the beginning when the guy came running out of the shack and the dinosaur came to life. Those shots were far from pleasing.

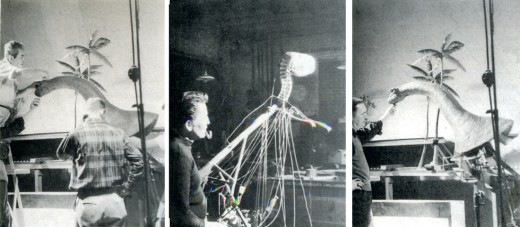

Project Unlimited technicians working on the large

manually-operated dinosaurs created for DINOSAURUS.

Left: Marcel Delgado applies the finishing touches to the Brontosaurus mockup.

Middle: Tom Holland and the Tyrannosaurs Rex “skeleton”.

CU: How big were the models in DINOSAURUS?

DS: Most of them were relatively small, except for the Brontosaurus, which was awfully big. You probably remember that we had a little doll of a boy riding on its back. I have a theory that large figures are hard to animate. Something happens, some strange phenomenon, which I can’t understand, takes place. I guess I’m not that kind of a perfect animator; I sort of do it loosely. I did TOM THUMB because that was all very contained. I got a lot out of the character as far as hand movements and so on. But the stuff that Jim Danforth did for BROTHERS GRIMM was just so superb that I would go insane doing that. I’m really into marionettes; I think that there’s a lot of potential in them for fantasy films in certain instances. I remember telling Gene Warren about some of those long shots where they were Trudging through the jungle in DINOSAURUS: “You know, I could do that better with marionettes.” I really think that one can augment the two.

CU: Project Unlimited also did some work on SPARTACUS…

DS: Yes, our little studio was always doing unusual props and effects for films, in between our animation jobs. Kirk Douglas was producing and starring in a monumental production of SPARTACUS, and Project Unlimited was called in to make about ‘ two or three hundred dead bodies, in various f scales, for some of the battle scenes. The largest * were about one-third life-size … We used molds to make them, and then we’d dress them in armor and sort of strew them all over the battlefields. I then i had to slash and “gore them up” with fake blood! We also made a bunch of horses out of polyure-thane foam. They weren’t very detailed, though-we just had to make sure they’d be recognizable from a distance, but none of them were shown in closeups.

CU: What did you do on THE TIME MACHINE?

DS: I worked on virtually all of the special effects.

There really wasn’t much animation, other than the decaying Morlock. That was done by Tom Holland. You know, I was in that film! I made my “screen debut.” Remember the guy in the window changing the clothes on the mannequin? That was me! I didn’t want the job because there was an actor there who worked with us, Dave Worrick. I asked them to give the job to Dave because I had no real desire to be in films. But they said, “No, we want you to do it.” So they got me a costume and animated me for the scenes.

CU: You mean you were actually pixillated as opposed to just speeding up the camera?

DS: Yes. I literally went in and they animated me per frame. The really neat thing about changing all of those costumes dealt with the fact that they were brought in from MGM. Somehow, in my subconscious mind, I recognized them. I remember saying to myself, “I’ll bet that’s a Lucille Ball dress.” Sure enough, it was, as their names are all sewn in them. But I loved the Morlock scenes. Some of the things I wish I had taken were a pair of Morlock feet and a Morlock head. They were great works of art; really spooky to look at! 1 animated the airplanes and dirigibles in the World War II scenes, but I never thought they were very realistic.

CU: In the earlier part of the film, there was a split-screen shot where boiling lava came oozing down the street. . .

DS: That was a great big fiasco, you know, because it didn’t really work. They had built these two bins full of colored oatmeal for the lava. One day, they decided to do a take. They covered all of the set with polyethylene. Now, they had prepared the oatmeal the night before, and nobody got up to look at it. Then they pulled the traps, with all these high-speed cameras going, and all the oatmeal had fermented and became watery. And the sight of all that! If I could have had a picture of the faces on those people! This foul-smelling, fermented mess came rushing down over all the cameras. I just went home. When they did the take again, they had put too much stuff together and it was too thick. I believe that’s how it appeared in the film. We were busy throwing burning cork and silvery material into the oatmeal, but it really didn’t work too well. It was fun, though.

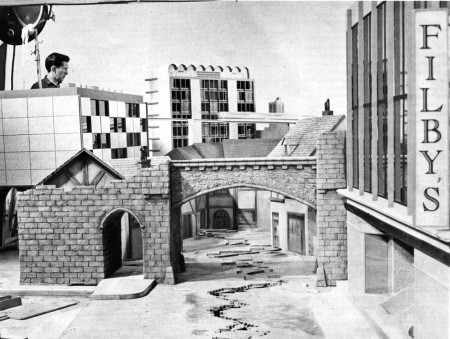

Don Sahlin on THE TIME MACHINE set.

Down this street will come the colored oatmeal “lava” flow.

CU: There was some inconsistency with the shot of you changing the mannequin. If the sun had been rising and setting at the speed depicted in the film, you shouldn’t have been able to see a man change a mannequin at all…

DS: Right. There are a lot of inconsistencies in that picture, but they’re very minor. It’s such a charming thing to watch. I never get tired of seeing it; it has such a haunting quality to it.

CU: Even the music and the actors seemed perfect.

DS: It did have a good score. Rod Taylor certainly seemed to be suited for the role. I had never been much of an Alan Young fan, but he played that triple role beautifully. And Yvette Mimieux was just out of high school at the time. The sound effects were great. I especially loved the off-camera sounds of the kettles underneath the ground.

CU: Did you work on the explosion scene towards the end?

DS: We had an incredible effect for that. We built a huge miniature set, about the size of a good-sized living room. It was all done on different levels of tables. We had legs underneath; and it was like a big puzzle. The legs were pulled at different times so the set would collapse. Then there would be explosions and flash-pots going off. It was really effective. There were many other scenes in THE TIME MACHINE that I worked on. There was the opening scene of the candles melting, and the ones of the flowers blooming. I remember we animated a snail; I also animated the Sphinx. You might recall the raising and lowering of those siren towers …

CU: Were they cardboard cutouts or was it a full miniature?

DS: It was dimensional. But there was very little animation involved in that. There was another scene, a blue-backing shot, where layers of lava were made to appear rising behind Rod Taylor in his Time Machine. That was all painted. They had a guy in another room, Bill Brace, an artist, and he was doing all those matte paintings where the trees were blooming and the apples were growing. And he painted the future scenes, too, where you saw the topography of the land changing, and the Eloi temple being built. The whole dome of that was a painting matted in, and the stairway leading up to it was part of MGM’s old QUO VADIS set.

DS: It was dimensional. But there was very little animation involved in that. There was another scene, a blue-backing shot, where layers of lava were made to appear rising behind Rod Taylor in his Time Machine. That was all painted. They had a guy in another room, Bill Brace, an artist, and he was doing all those matte paintings where the trees were blooming and the apples were growing. And he painted the future scenes, too, where you saw the topography of the land changing, and the Eloi temple being built. The whole dome of that was a painting matted in, and the stairway leading up to it was part of MGM’s old QUO VADIS set.

Do you know what I loved about working on TIME MACHINE? We literally did the sets ourselves. I loved doing the sets and dressing them. We were all very involved in the whole project instead of just one aspect of it. I remember working on that huge hole that Rod Taylor climbed into to get to the Morlock world. I loved getting down there, touching it up with a spray can and adding little details to it. I really feel proud to say that I worked on THE TIME MACHINE; I think it was a classic. I never received screen credit due to the politics of the organization, but it never bothered me. We were working on a very small budget. I think I remember Gene telling me that we did the effects for under $60,000, which was really a smal sum, yet it reaped an Academy Award. Have yot ever met George Pal?

CU: We’ve never had the pleasure.

DS: When you think about him, he was such an unusual producer when you realize the courage he had to have to do the kind of offbeat things he did.

CU: The last film you worked on for him was THE WONDERFUL WORLD OF THE BROTHERS GRIMM. Could we talk about what you did on that one?

CU: The last film you worked on for him was THE WONDERFUL WORLD OF THE BROTHERS GRIMM. Could we talk about what you did on that one?

DS: I did a lot of the animation, especially the scenes involving the elves. The opening scene of the elves took me a whole week to do. Dave Pal and George’s other son, Peter, worked with me. We got along famously. I had to leave before the picture was over, so Dave carried on from where I left off.

CU: Did you work with Jim Danforth on the film?

DS: Not directly. I was in one corner of the stage, and Jim was working in the other corner. It was so tedious because of the Cinerama camera. Each frame had to be photographed three times. You had to be careful not to make any mistakes. We couldn’t talk at all. Peter would work the camera and we made it a point never to talk to each other because it was so easy to make an error. I was animating five elves, and he had to work that complicated turret camera.

CU: Didn’t you have to brace some of the elves? Some of them had to leap off the stage. . .

DS: Yes. We had a lot of wire stuff on the film. The wires were very thin and they were coated with iodine. You really couldn’t see them. Each time we’d reposition the puppet, the wires would be in a different part of the frame. So they really cancelled themselves out.

CU: Did anything unusual happen on the animation set?

DS: I do remember one funny thing that happened on BROTHERS GRIMM. There was a scene where an elf walked across the set with a shoe. The peg holes, by the way, were covered with clay and painted to match the set each time the elf took another step. Anyway, one of my little mice from the aborted TAILOR OF GLOUCESTER project got into a frame while the elf was being animated. Just for one frame. It was a terrible thing, but Pal never saw it!

CU: Did you do anything outside of the elf sequences?

DS: Wah Chang set up all of the shots and lit them. While he was doing that, I loaded the camera, which to this day frightens me because I don’t consider myself that technically inclined. I also did all of the calibrations and animated the camera for trucking shots. All the fades and the simpler opti-cals were done in the camera.

CU: Did you actually plot out all of the animation before it was photographed?

DS: We had to on some of the things. When there are faces involved as there were in TOM THUMB, and you have to do all the vowels and so on, you have to plot them out beforehand. But I like to animate sort of “free;” I don’t like to be restricted too much. You mentioned Jim Danforth before. I believe I met him while I was doing TOM THUMB. He was very young at the time and was very wide-eyed at what was going on. He seemed so impressed with our setup. Then I saw his reel that he had done in his garage. He did incredible stuff, op-ticals and everything. He’s a genius; he really is an incredible animator. He’s so much better than I am because I haven’t the patience to do the detail that he does. I remember him animating the dragon in BROTHERS GRIMM. He did that whole thing, and he spent days with all sorts of pointers. He’s a perfectionist.

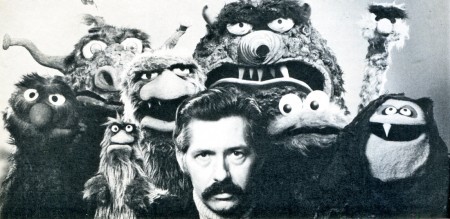

CU: Now that you’re no longer involved in stop-motion, could you tell us about your work with the Muppets?

DS: I build and co-design Jim Henson’s puppets. He starts out with a little thumbnail sketch; I would say that he really creates the essence with his sketch. Then I start building it. Jim comes in and looks at it and we play with them to see how well they’ll work. But it’s really a joint effort, although I don’t do any of the puppeteering. I built many of the most famous of the Muppets. Kermit the frog, Bert and Ernie, the Cookie Monster, and most of the others.

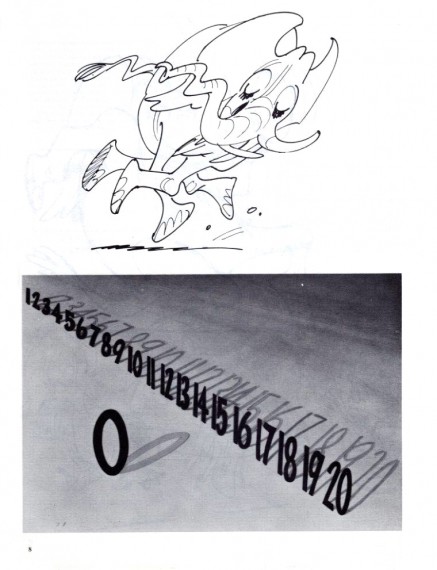

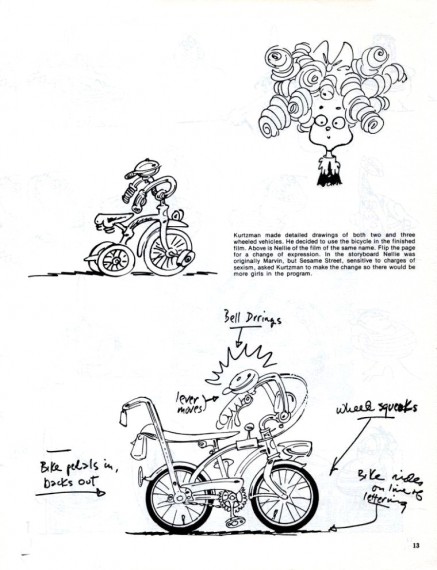

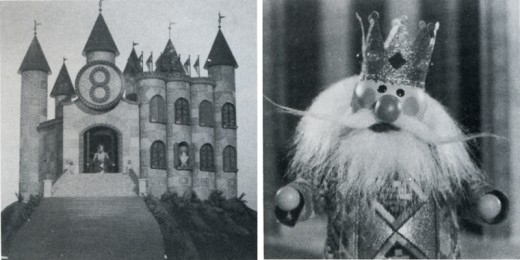

CU: You did two “counting films” for Sesame Street. . . were these very recent?

DS: Not really. They were done around 1970, right here in our Muppets, Inc. offices. Jim Henson supervised the filming, but he gave me all the freedom in the world to do what I wanted. THE QUEEN OF SIX was filmed on a rug, to simulate grass, and the backgrounds were all painted cardboard. The Queen figure was about 13 inches tall and I wanted her to have a very baroque, dresden sort of look. Her hoop skirt was a big lampshade that I put brocade on. She had a beautiful Marie Antoinette wig that I made out of silver thread, and I used one of those plastic Easter eggs you can buy for her head.

DS: Not really. They were done around 1970, right here in our Muppets, Inc. offices. Jim Henson supervised the filming, but he gave me all the freedom in the world to do what I wanted. THE QUEEN OF SIX was filmed on a rug, to simulate grass, and the backgrounds were all painted cardboard. The Queen figure was about 13 inches tall and I wanted her to have a very baroque, dresden sort of look. Her hoop skirt was a big lampshade that I put brocade on. She had a beautiful Marie Antoinette wig that I made out of silver thread, and I used one of those plastic Easter eggs you can buy for her head.

CU: I recall the other “counting film” you did, THE KING OF EIGHT, with the rhyme-speaking king, and his eight daughters opening and closing the windows of his castle. Both of these films were fairly short, weren’t they?

DS: Yes, none of those films done for Sesame Street are over a minute in length.

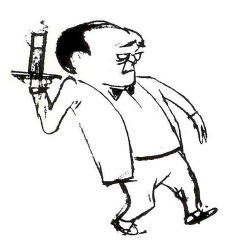

The King of Eights

CU: Are you satisfied with the work you’re doing now?

DS: Certainly. It’s very creative and enjoyable. I remember that when I was a kid, my sister wanted me to take regular college courses. I told her I wanted to take art courses. She would say, “What can you do with art? You’ll never make a living do ing puppets.” And it was only recently that we reminisced about that and, not trying to sound egotistical, I said to her: “Do you know that my puppets are all around the world?” Now that Sesame Street has been distributed in Europe, I have great satisfaction in knowing that my creations are

being seen and enjoyed internationally.

Don, as he appears today, with some of his more

“gruesome” creations for the Henson MUPPETS.

Articles on Animation 30 Mar 2010 07:21 am

Mel Blanc Intvw

- The following interview with Mel Blanc appeared in the Nov, 1985 issue of Video Times Magazine. By this time, Mel Blanc was on automatic pilot. He’d answered these same questions hundreds of times, so there may not be much original information here. I think it’s informative and entertaining just the same.

- The following interview with Mel Blanc appeared in the Nov, 1985 issue of Video Times Magazine. By this time, Mel Blanc was on automatic pilot. He’d answered these same questions hundreds of times, so there may not be much original information here. I think it’s informative and entertaining just the same.

A Thousand Voices

Mel Blank Croons a Looney Tune

Editor’s Note: We could think of no better way to end our special report on children’s video than to chat with the one man whose name has become synonymous with some of the most-beloved cartoon characters: Mel Blanc, better known as the voice of Bugs Bunny, Porky Pig, Daffy Duck, and many other zany cartoon characters. Gregory Cat-sos recently caught up with this 77-year-old Tasmanian devil (who is still working a full schedule) for a short conversation.

VIDEO TIMES.- Who is your favorite cartoon character?

Mel Blanc: Bugs Bunny. Bugs is the closest to me. He’s my favorite character because, without him, I don’t know what might have happened. He’s been more or less my main leading character. Not long ago, Warner Brothers conducted a poll among 10,000 children to determine what cartoon characters they liked best. Bugs Bunny came out number one. That made me realize how popular this “cwazy wittle wabbit” is. I hope it continues on that way.

Mel Blanc: Bugs Bunny. Bugs is the closest to me. He’s my favorite character because, without him, I don’t know what might have happened. He’s been more or less my main leading character. Not long ago, Warner Brothers conducted a poll among 10,000 children to determine what cartoon characters they liked best. Bugs Bunny came out number one. That made me realize how popular this “cwazy wittle wabbit” is. I hope it continues on that way.

VT: What character that you do is your real voice closest to?

MB: I’d say Sylvester, the cat, is the closest to my straight voice. I almost sound like him in real life.

VT: Each cartoon character you ‘ve created is different from the other.

MB: I always tried to make each character different or unusual. These characters have their own peculiarities, their own unique personalities. Like Daffy Duck’s crazy laugh, Bugs Bunny’s style of talking, Porky Pig’s stuttering, and the “spraying” sound of Sylvester when he talks.

VT: Warners has released a series of classic cartoons on videotape: Bugs Bunny’s Wacky Adventures, Daffy Duck: The Nuttiness Continues, A Salute to Mel Blanc, and others. How do you feel about this?

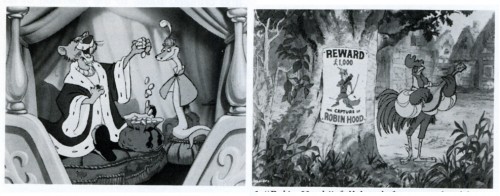

MB: I’m happy about it. People with video machines can now collect some of their favorite cartoons. The Salute to Mel Blanc tape contains some of my personal favorites: “The Rabbit of Seville” (1950), “Robin Hood Daffy” (1958),

“Ballot Box Bunny” (1951), and “Bad O1* Putty Tat” (1949).

VT: How many cartoon voices have you provided these past 50 years?

MB: For Warner Brothers alone I did about 700 different voices. I can also do 400 more different voices and dialects. So when they call me, The Man of 1000 Voices, they’re not kidding.

VT: Besides Warner’s cartoons, who else have you worked for?

MB: I’ve done the voices of Barney Rubble and Dino the Dinosaur in The Flintstones. I’m doing voices again for The Jetsons, with Penny Singleton. I also provided the original voice of Woody Woodpecker in 1936. Walter Lantz had asked me to create a voice for his woodpecker character. 1 did a few cartoons for his studio. But I had to stop doing Woody’s voice when I signed an exclusive contract with Warner Brothers. After that, a woman named Grace Stafford did the voice. I guess Walter Lantz didn’t want to lose her, so he wound up marrying her (laugh).

VT: Are there any voices that you Haven’t provided in the Warners’ cartoons?

MB: I did practically everybody except Granny (in the Sylvester and Tweety Pie cartoons). And in the beginning, I didn’t do Elmer Fudd. His voice was done for many years by Arthur Q. Bryan. After Bryan died in 1958, I began doing Elmer. But I didn’t want to imitate Bryan’s voice. 1 did my own interpretation of Elmer’s voice. I don’t like to imitate. I’m a creator of voices, not an impersonator.

VT: When did you start doing cartoon voices?

MB: In 1936. I did a drunken bull character in a cartoon called “Picador Porky.” Initially, I had some difficulty getting into the cartoon business. I tried many times to get an audition at Warner Brothers, but I was always told, “Sorry, but we have all the voices we need.” I kept going back for over a year and a half, but the man in charge still said, “No.” Finally, this man died. So I went over to Treg Brown, who was the head of the sound-effects department of animation, and asked for a job.

Treg listened to my audition and liked it. He even had me audition for some directors and producers at the studio. One director, Tex Avery, said to me, “Can you do a drunken bull?” I said, “I think so.” And Tex asked, “What would he sound like to you?” So 1 did my impression of what I considered to be a loaded bull, hiccuping and slurring my speech. He said, “That’s perfect! What are you doing next Tuesday?” Well, I wasn’t doing a damn thing. But I said, nonchalantly, “Oh, I think I can make it” (laugh). That’s how it all started.

VT: Did you also do Porky Pig’s voice in “Picador Porky”?

MB: No, I didn’t do Porky Pig at the time. The studio had a man there named Joe Dougherty, who actually stuttered in real life, who was then doing Porky. But this guy had problems coming in on cue and doing the dialogue properly. So the studio asked me if 1 could stutter on cue, to do Porky’s dialogue with the right timing, I did my interpretation of Porky’s voice for them, and they liked it.

VT: What was the first cartoon in which you did the voice of Porky Pig?

MB: 1 think I did Porky’s voice for the first time in “Porky’s Romance” in 1937.

VT: Did you have scripts for the cartoons?

VT: Did you have scripts for the cartoons?

MB: Absolutely, but first the writers showed me the storyboard. Through a series of pictures, the storyboard showed what the cartoon was about and what the characters would say and do. Then I created the voices.

VT: How long did it take the animators to make one cartoon?

MB: It would take 125 people about 9 months to make one 6-1/2 minute cartoon. Of course, they all worked on more than one cartoon at a time. These animators were all specialists. One would draw Bugs Bunny; another would create Daffy Duck; another would do the backgrounds, and so on.

VT: How long did it usually take you to do the voices for one cartoon?

MB: About an hour per voice. Originally it would take me about a day and a half to do all the voices. The voice is done first, you know. From the voice the animator draws pictures to fit the mouth movements. The animator looks in the mirror and copies his own mouth movements on the character and captures the right facial expressions. My dialogue is also timed with the footage.

Eventually, I suggested to the directors, “Why don’t you record each character individually? Let me do each voice first!” This way, I didn’t have to jump back and forth anymore. So they recorded each character’s lines individually. It saved a lot of time and money for the studio, and it was a lot easier for me this way.

VT: How much freedom did you have in contributing to the characters or the dialogue?

MB: I was given a lot of freedom with the cartoon characters, especially in contributing to their dialogue. I sat in on the story conferences and gave the writers and directors some of my own ideas. In many of the cartoons, I more or less ad-libbed a lot. My ad-lib was timed to the exact second. If I didn’t feel that certain dialogue was appropriate for Bugs Bunny, I ad-libbed something better or more in character for him, or I suggested substituting another line. And 99 times out of 100, the director agreed that my ad-lib or change in dialogue was better than what was in the script. For example, they were originally going to have Bugs say, “Hey, what’s cooking?” in all the cartoons. I said, “Instead of that corny expression, can’t we use a funny expression that’s been going around, What’s up, Doc?” The writers agreed that sounded better, and we used that catchphrase instead. I also ad-libbed something in “Knighty Knight Bugs” (1958). King Arthur sent out Bugs Bunny, the court jester, to take away a singing sword from the Black Knight (Yosemite Sam). After recapturing the sword, Bugs was supposed to say, “So this is the singing sword? How do you like that?” But instead, I said, “So this is the singing sword? Big deal!” 1 ad-libbed, “big deal!” It sounded better than the original line, and Friz Freleng, the director, kept it in.

VT: When Bugs Bunny chews on a carrot and says, “What’s up, Doc?” are you really chewing on a carrot?

VT: When Bugs Bunny chews on a carrot and says, “What’s up, Doc?” are you really chewing on a carrot?

MB: Yes, I actually chewed on a carrot. We had originally tried potatoes and celery but discovered the only-things that made the sound of a carrot was me chewing on a real one. But when 1 got a mouthful of carrot, I couldn’t swallow it all in time and then talk like Bugs. So, we’d stop recording for a moment, and I’d spit the carrot out in the wastebasket. Then, I would go on with the rest of the dialogue. I used to fill a few waste-baskets a day in order to do a little dialogue.

VT: Why does Bugs Bunny kiss Elmer Fudd on the lips in many cartoons? What’s that all about?

MB: The writers had put it in to get some more laughs in the cartoon. They thought this would be funny. At the time, we didn’t think anything of it. It was just an unexpected thing for Bugs to do. Elmer Fudd is pointing his shotgun at Bugs. Instead of being afraid, Bugs grabs Elmer and kisses him! Now, a rabbit kissing a man, in itself, was ridiculous. It got a good laugh and they kept using the gag. Warners had some marvelous and inventive writers in those days. They experimented with a lot of gags for Bugs that would look absurd. This was one of them, When I talk at colleges, some students will ask, “How come you never know what Bugs is? He keeps kissing Elmer and the other guys.” And 1 answer, “Bugs is not gay.” It’s just a gag that worked, and the writers used successful gags over and over. VT: What other gags were used a lot? MB: They had several running gags. Like the funny little signs Bugs or Daffy held up saying, “Funny isn’t he?” In one Road Runner cartoon, “Gee Whiz-z” (1956), the coyote falls off a cliff and holds up a sign saying, “How about ending the cartoon before I hit?” Another gag is, Bugs opens a door and finds another door behind it, followed by another door, and so on. Or Elmer Fudd points his shotgun at Bugs. Then, Bugs bends the barrel of the shotgun back the other way, so now it’s pointing at Elmer instead.

VT: When was Daffy Duck introduced?

MB: Daffy Duck was introduced in “Porky’s Duck Hunt” (1937). The cartoon was very funny and ended with Daffy hopping up and down, laughing over the “That’s all, folks” title card.

VT: When were Tweety and Sylvester introduced?

MB: In two separate cartoons. Tweety, the canary bird, was introduced in “Birdy and the Beast” (1944). Sylvester, the cat, made his debut in “Life with Feathers” (1945).

VT: How did they come up with Tweety Bird’s expression, “I taw a puttytat”?

MB: I said that phrase at one of the meetings—one of our story conferences. The writers thought it was a catchy line, and we used it in the Tweety cartoons. The same thing happened for Sylvester’s expression “suffering succotash.” We developed all these kinds of lines at our meetings.

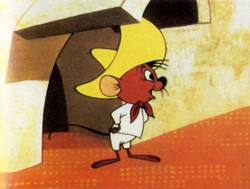

VT: How about Pepe le Pew, foghorn Leghorn, Yosemite Sam, and Speedy Gonzalez? When were they introduced? MB: Pepe le Pew made his first appear-ance in “Odor-able Kitty” in 1945, Foghorn Leghorn in “Walky Talky Hawky” in 1946, and Yosemite Sam in “Hare Trigger” in 1945. Speedy Gonzalez’s first cartoon was “Cat Tails for Two” (1953). That shows you how long these characters have been around.

VT: How about Pepe le Pew, foghorn Leghorn, Yosemite Sam, and Speedy Gonzalez? When were they introduced? MB: Pepe le Pew made his first appear-ance in “Odor-able Kitty” in 1945, Foghorn Leghorn in “Walky Talky Hawky” in 1946, and Yosemite Sam in “Hare Trigger” in 1945. Speedy Gonzalez’s first cartoon was “Cat Tails for Two” (1953). That shows you how long these characters have been around.

VT: How about the Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote?

MB: The Road Runner and the Coyote made their first appearance in “Fast and Furry-ous” (1949). This was the first time the Coyote chased the Road Runner in the desert. Chuck Jones was responsible for creating this series. I didn’t do the voice in the first Road Runner cartoon. The studio used a Klaxon horn to make the beep sound. I started doing the cartoons after the first one was made. One day, the studio couldn’t find their Klaxon and asked me to do the sound.

VT: What kind of director is Chuck Jones?

MB: Chuck Jones is a great director. When Chuck directed me he told me exactly what he wanted to convey in the cartoon. He’d also do some of the dialogue beforehand to demonstrate what he wanted me to do with the lines, the voice inflection, and the pauses between the lines. All of Chuck’s cartoons are well structured. In his Bugs Bunny cartoons, Chuck usually showed a reason for Bug’s mischievous behavior. Bugs Bunny is usually minding his own business in the rabbit hole. Then Elmer Fudd or somebody else comes along and bothers him. So Bugs says, “Of course, you know this means war!” and fights back. VT: What, in your opinion, are Chuck Jones’ funniest cartoons? MB: I think many of his Road Runner cartoons are very funny, such as “Zoom and Bored” (1957) and “Hook, Line, and Stinker” (1958). Warner Brothers has released a videotape titled, A Salute to Chuck Jones. On it are some of his greatest cartoons: “Duck Dodgers in the 24′/2 Century” (1953), “For Scentiment-al Reasons” (1949), and “What’s Opera, Doc?” (1957).

VT: Musical backgrounds are prominent in Warners cartoons, aren’t they?

MB: Yes, music was an important ingredient. Carl Stalling—and later on, Milt Franklyn—musical directors, used many popular melodies to advance the plot of the cartoons. They tried to make the melodies fit the situations. For example, if there was a lady in a red dress, their orchestra played “The Lady in Red.” If a character was leaving on a trip, you’d hear “California, Here I Come.” Something about Hollywood or movie stars would be “You Oughta Be in Pictures” or “Hooray for Hollywood,” and so on.

VT: Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck do a lot of singing in the cartoons. Why?

MB: The studio knew I could sing pretty well and that I was also a musician. So the directors asked me to do some singing in the different voices I did. In Bugs and Daffy’s voices I sang bits and pieces of songs like “Someone’s Rocking My Dreamboat” or “Singing in the Bathtub.” In the “Rabbit of Seville” (1950), 1 had Bugs sing “Figaro.” In fact, Carl Stalling even wrote a special song for Bugs to sing called “I’m Glad I’m Bugs Bunny.”

VT: Do you get residuals when your cartoons are shown on TV?

MB: Yes, I do. It’s in my contract with Warner Brothers.

VT: For most of your career not many people knew it was Mel Blanc doing ait those cartoon voices. Did that bother you?

VT: For most of your career not many people knew it was Mel Blanc doing ait those cartoon voices. Did that bother you?

MB: Yes, 1 kind of felt bad because the cartoon characters themselves had become so popular. When I finally did the American Express commercial a few years ago, people became aware of who I was. But I used to go to restaurants and nobody recognized me. Now, 1 can’t walk down the street or into a restaurant without somebody asking me, “Hey, have you got your American Express card with you?” And I answer, “Yes, I don’t leave home without it!”

VT: What’s next for Mel Blanc?

MB: All I can say is, “That’s not all folks!”

— GREGORY J. M. CATSOS

Articles on Animation 27 Mar 2010 08:13 am

Harald Whitaker / Don Hahn

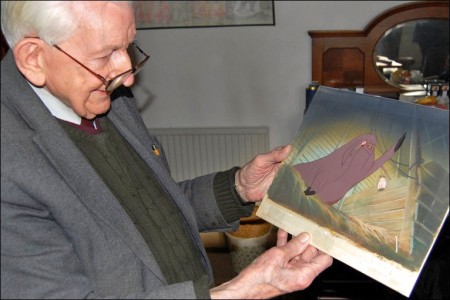

- I wasn’t aware that Harold Whitaker was still alive and kicking until I’d received this note from Animal Farm aficionado, Chris Rushworthy:

- I wasn’t aware that Harold Whitaker was still alive and kicking until I’d received this note from Animal Farm aficionado, Chris Rushworthy:

- I came across this BBC online article the other day. It has some very interesting images of Harold Whitaker and some of his Animal Farm collection. I salivated over the original background shown for the Old Major speech scene of which I have most cels and camera sheets.

Go here to see the pictoral piece.

Whittaker, of course, was the leading animator at the Halas & Batchelor studio for many years. After retiring from H&B, he wrote the book on Animation Timing that, to me, is one of the finest books available on animation production. The book, Timing for Animation, was recently updated by Tom Sito and is widely available. Everything in the book is explained in a deceptively simple way, yet it beams with clarity few other animation books achieve. I haven’t seen the updated version of the book, though I’m sure it stays true to Whitaker’s original.

Many thanks to Chris for directing me to this piece from the BBC; the photos are first rate.

Go here to visit Chris Rushworthy’s excellent site built around his collection of Animal Farm artwork.

Whittaker (front center) at the Anson Dyer studio.

____________________

– With the opening yesterday of Waking Sleeping Beauty, there’s a timed interview with Don Hahn in the Onion’s AVClub. It’s a long and excellent read with some pointed questions asked and answered. Here, for example, is one that caught my eye:

AVC: The story the film is telling changes throughout the film. It starts out being about the animators, and it ends up being about the executives. Did you always start out with that arc? Did it change as you got access to some of these people?

AVC: The story the film is telling changes throughout the film. It starts out being about the animators, and it ends up being about the executives. Did you always start out with that arc? Did it change as you got access to some of these people?

DH: We had access from the beginning. Some of the earliest talks we did were with some of the executives. I think what we wanted to do though, was—I didn’t want to create class distinctions between executives and artists. I didn’t want to create a good-guy/bad-guy scenario from the very beginning. I think that’s a little simplistic. The truth is, without the executive boldness and the artistic achievement, it wouldn’t have happened. I don’t think we even use the word “executive†in the movie. We talk about these people. We talk about who they are and what they do, but it was important to show that everybody had a role at the table, and if you pulled one of those people out, the checks and balances would be thrown off a little bit.

So the arc of the story was somewhat determined by what literally happened. It was a group of lost boys, a group of people right out of school with big dreams that couldn’t be expressed yet. And then having Wells and Eisner and Katzenberg come into the studio—at the same time Howard Ashman comes in—and you have this tremendous renaissance, a change in the approach, outsiders coming in, Roger Rabbit happening, and this huge growth in the potential of animation that culminates in great financial success, that culminates in some egos getting in the way. Then Frank Wells’ death is the domino that pushes over and starts to unravel a lot of those situations, which culminates in the end of the movie.

The film is a must-see for anyone connected with animation who takes Disney films seriously. It’s a strong entertainment and a producer’s vision of what he saw while living through it. Currently it’s at the Landmark Sunshine Theater in New York.

____________________

Articles on Animation &Bill Peckmann &Daily post 19 Mar 2010 08:30 am

Animation Overview – 1976

Here’s another survey of the year in animation for the March/April issue of Print Magazine circa 1976. Leonard Maltin did the surveying. Interesting that you don’t see many of this type article anymore.

Overview

by Leonard Maltin

British animator Bob Godfrey has said, “Animation is a medium that deserves masters worthy of it. I’d like to see animation Picassos or Matisses, and we haven’t had any so far.”

Of course, Matisse never had to raise two million dollars in order to create one of his paintings, and Picasso didn’t have to oversee a staff of inkers and painters to make sure his newest canvas would turn out right.

The artist who chooses animation as his medium must endure certain realities: that films cost money, that extensive filmmaking becomes expensive filmmaking, and that except for the most monastic souls filmmaking is a collaborative process. This is not to eliminate the possibility of individual artistic expression in animation, but there are simpler ways known to man.

Once the artist has made his film, another set of realities comes to the fore: trying to find a distributor, or at least an audience, and with any luck, establishing a way of recouping the monetary investment of making the film. Since individual backing is hard to come by, to examine “the state of the art” of animation is to examine “the state of the industry” at the same time; it’s nearly impossible to separate the two.

In this country—as around the world— animation means so many different things that even the most cursory observations can expand to extreme lengths. “Animation” covers a lot of ground, from high-school kids filming paper cutouts with a Super 8mm camera to major Hollywood factories turning out Saturday morning drivel by the carload, but there are some significant outposts along the way.

“Robin Hood” full length feature produced by Walt Disney Prods.

Producer/Director Wolfgang Reitherman

Rumors of the Walt Disney Studio’s abandonment of cartoons are greatly premature. There was a time several years ago when the future of animation at the studio was in doubt, but the whopping worldwide success of the animated Robin Hood is just one reason that animated features are an ongoing project in Burbank.

The studio’s current endeavor is The Rescuers, which concerns two detective mice who head a society of do-gooders. Like other recent Disney features, it will comprise some four years of work— anywhere from three to four times as much as most competitors spend on similar projects. Rescuers is being aimed for Christmas of 1977, but there’s no guarantee that it will be completed on time. No one rushes this group of craftsmen.

The two main objectives in any Disney feature are a strong story line, the backbone of the film, and equally strong personality development, which gives the film its heart. Unfortunately, the approaches to these objectives have become increasingly routine in the 1960s and 70s at Disney, with much of the personality emanating from big-name stars doing character voices, and not so much from the animator’s pencil, although character animation is still superbly handled.

Practically everyone working on The Rescuers in a major capacity has been at the studio for 30 to 40 years, and Frank Thomas, a senior member of the team, admitted to John Canemaker, “We are less experimental. [With Walt] every picture was completely different. We were always pushed into things that were exceedingly difficult to do. He was always asking us to rise above ourselves. Well, when he left it up to us, we quit that. We got old. We decided we were going to do the things that were fun to do.”

The quality is still there, and the years of care and precision that go into a Disney feature show up on the screen. But somehow, the magic is missing, and that has nothing to do with time or money.

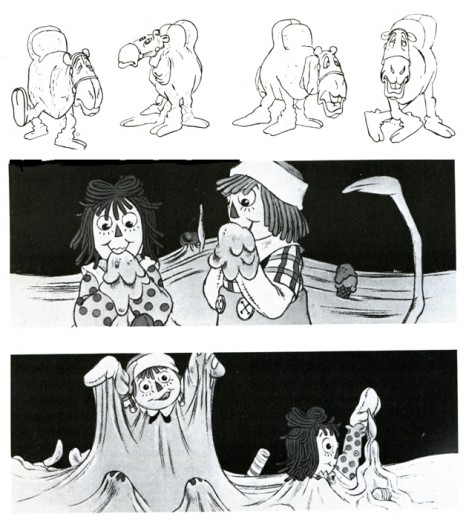

“Raggedy Ann & Andy” upcoming feqture based on Johnny Gruelle’s characters.

Production company: Lester Osterman Prods. Supervisor/director: Richard Williams

Into the breach steps a young man who has been hailed as “the new Disney,” Richard Williams. Canadian-born, British-based, he has impressed the animation world with his main titles for feature films (Charge of the Light Brigade, Return of the Pink Panther), theatrical shorts (“Love Me, Love Me, Love Me”), television specials (A Christmas Carol), and commercials.

The comparison with Disney is apt, because Williams has devoted himself tirelessly to the improvement of his work. Several years ago he began recruiting veteran Hollywood animators to come to London and work with his staff, as artists-in-residence, teachers, and colleagues. These men, in their 60s, 70s, and 80s, have all contributed to Williams’ pet project, an animated feature entitled The Cobbler and the Thief, which has been in progress for the better part of a decade. Williams and his people work on this when there is time, between commercial assignments. Among the distinguished Disney, Fleischer, and

Warner veterans who have pitched in are Art Babbitt, Shamus Culhane, Grim Nat-wick, and Ken Harris. It’s a two-way love affair, a happy collaboration between men of age and experience and younger animators with fresh ideas and outlooks.

Now Williams is hard at work on an ambitious American project, a musical feature version of Raggedy Ann and Andy set for release at Christmastime this year. He has gathered a hand-picked staff in New York and supplemented it with freelancers from places as far off as Arizona.

Oher animated features are also on the way. It took Fritz the Cat to convince distributors and theater-owners that animated films shouldn’t be regarded as kiddie-show fodder and nothing more. Now John Hubley is directing a cartoon version of the bestseller Watership Down, while Fritz’s director, Ralph Bakshi, is working on his fourth feature film (the third, Hey, Good Lookin’, is about to be released). Producer Lee Men-dohlson and director Bill Melendez are working on a third Peanuts feature in California, while a New York operation has completed a feature-length remake of Tubby the Tuba. Other features are in production and planned for the near future.

But feature films tell only part of the story. Many filmmakers, amateur and professional, work in the realm of short subjects, and bringing these to the attention of an audience, not to mention a distributor, can be a long and wearisome process. One splendid showcase is the annual awards competition sponsored by the New York branch of ASIFA, the international animation society. Their recent screenings of this year’s winners revealed much about trends, goals, and styles in current films.

In the Student Film Category were three astoundingly professional products: Eduardo Damino’s “Hello,” a slick, imaginative treatise on the history and impact of telephones, using colorful cutout animation and an abstract soundtrack; Stephen Ciodo’s “Cricket,” a finely crafted stop-motion film for children about a cricket who is ostracized by his peers because he’s unable to jump; and Linda Heller’s “Album,” a most intriguing series of vignettes based on flashbacks and flash-forwards in a photo album of a woman’s life.

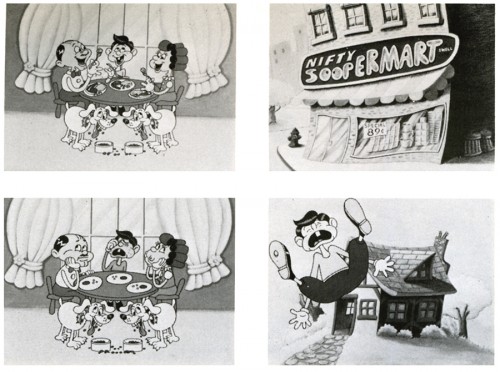

“A Dog’s Life” Due to soaring food prices, a family eats less while their dogs eat more.

Production company: Perpetual Motion Pictures | Producer: Marshall Patinkin

Director/designer: Hal Silvermintz | Animator: Vince Cafarelli

A vital category for prizes at ASIFA East is the Non-Sponsored Professional Film. Chapter president Dick Rauh explains that this category is intended to encourage members to take the time to make personal films, apart from their daily assignments; indeed, the five winners showed a wide range of highly individual styles and goals.

Mary Beams’ “Going Home Sketchbook” has an interesting visual concept, combining sketches, line animation, and what seems to be a rotoscope technique to create an impressionistic view of a trip home; unfortunately, there is no development within the film to give it any real interest beyond that technique. “Deep Sleep” is a feminist-oriented film by Peggy Tonkonogy that details a woman’s long, weird symbolic dream; again, an aimless-ness is somewhat compensated for by excellent visual effects. Both of these films received Honorable Mention.

George Griffin’s “L’Age Door” is an irresistible film that perfectly meshes form and content as a man is confounded and swallowed up by an endless succession of doors. Short, sweet, and quite funny. Griffin’s film won Third Prize in this category.

“Quasi at the Quackadero,” Second Prize-winner, is one of the most bizarre animated films I’ve ever seen. Sally Cruickshank’s visual extravaganza bears repeated viewings, just to absorb everything that’s happening on-screen; the style might be described as freaked-out George Herriman. Significantly, Cruickshank labels her film “a cartoon,” showing strikingly-designed characters attending a futuristic amusement park where the games and rides are based on time- and life-warps.

First Prize was awarded to Kathy Rose for her quiet and enjoyable film “The Doodlers,” the basic premise of which is that drawings beget drawings.

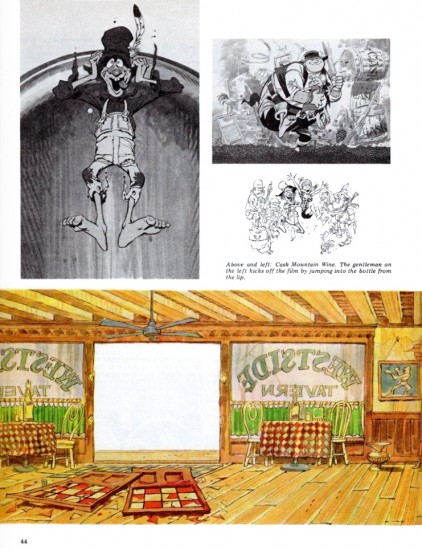

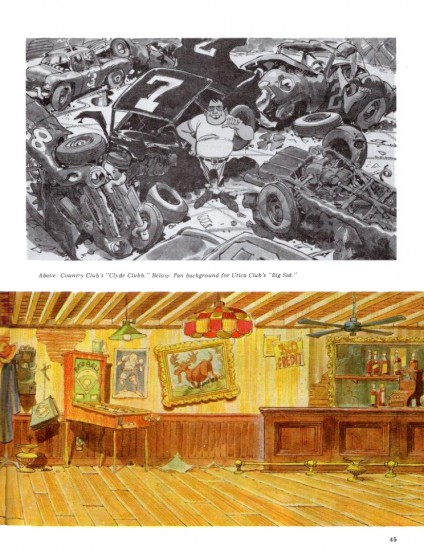

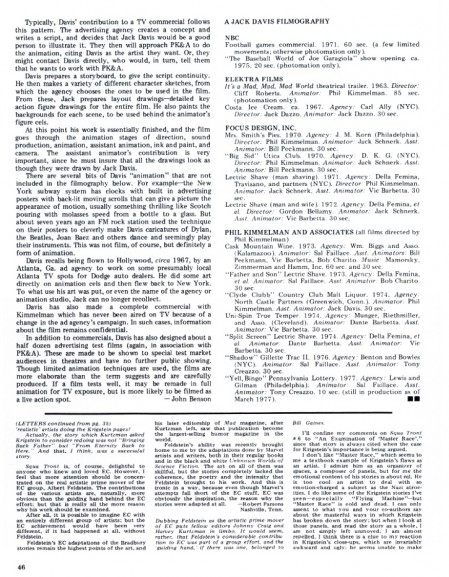

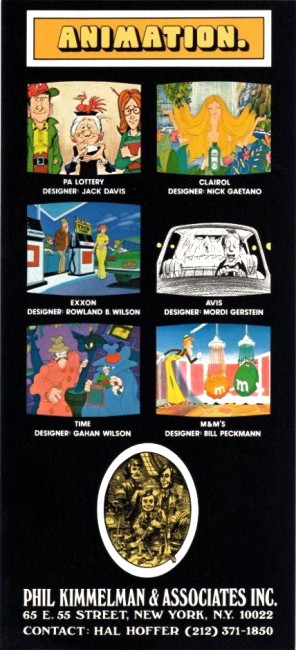

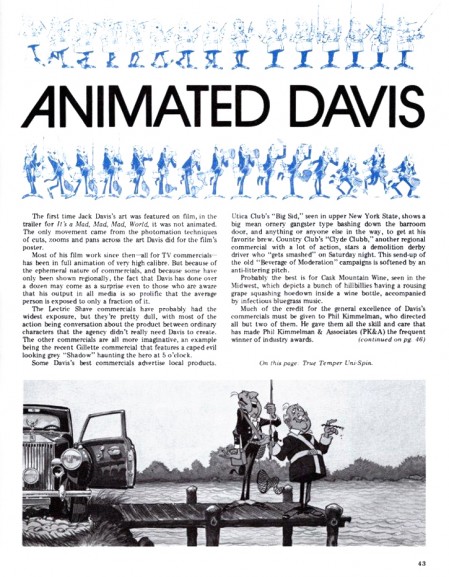

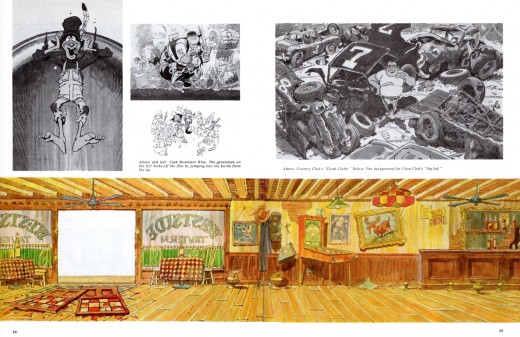

In the general categories, awards were divided according to soundtrack, technique, script/concept, humor, design, animation, and direction. Most of these were commercial and/or sponsored films, including several delightful commercials from Phil Kimmelman and Associates, a funny NBC “Weekend” gag-film by Ovation Films, some dazzling 7-Up graphic spots by Goldsholl Associates, and two fine shorts by the Wantu Studio headed by the talented James Simon.

“Whazzat” Clay figure animation based on blind man and the elephant

Sponsor: Encyclopedia Britannica |Production company: Crocus Pictures

Producer: Tel C. Determan | Director: Art Pierson

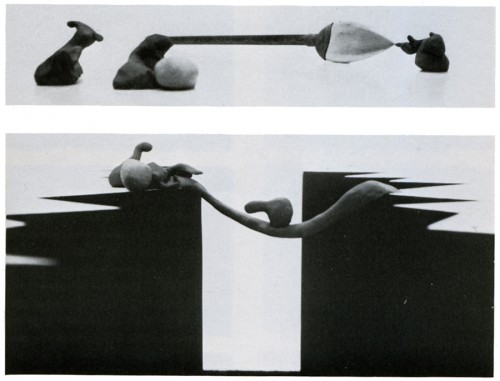

Awards for Best Animation and Best Direction went to Arthur Pierson and his associates Ron Lasner and Alan Baker for a disarming stop-motion clay film called “Whazzat?” (which had already won Spe-cialJury Prize for Best Film at the New York Animation Festival). The premise of “Whazzat?” has six clay objects assuming vivid personalities, although they have no faces or identifying features; together, they travel and enjoy each other’s companionship, until they come upon a strange being unknown to them. Through sophisticated and knowing animation, camera placement, and ingenious use of soundtrack, “Whazzat?” makes something special out of something elegantly simple.

Best Film in ASIFA’s competition was another repeater from the New York Festival, Stan Phillips’ “Water Follies,” produced as a soft-sell promotional film for the Denver Water Commission. An entertaining series of blackout gags on uses and abuses of water, this straightforward film quietly goes about its business and scores a bull’s-eye with its entertaining point of view and uncluttered animation style.

One may be hesitant to accept the idea of slick, professionally sponsored films competing with more personal, individual works. But the ASIFA screening brings out something very important about animated films. They come from individuals and they come from large companies; they range from utter simplicity to overstuffed detail, from quietude to clutter. But each film stands on its own, with its own set of goals to be met, and if it fails, all other considerations become worthless.

Not every professional film is better than an amateur effort. There are films made by eight- or nine-year-olds which burst with imagination and daring visual ideas; they put some professional filmmakers to shame. Likewise, some one-minute TV commercials are so outstanding in every respect (animation, design, humor) that they overpower more “serious” artistic works shown alongside them.

But does the film succed on its own terms? Be it Disney, Bakshi, commercial or collegiate, that’s the only question that really counts.

1

1  2

2  3

3

1.”Teeth Care” Sesame Street – Prod/Dir: James Simon Animator: Jack Schnerk

2. “The Strike” Morris Funk Foundation Prod/Dir: James Simon

Animators: Cosmo Anzilotti, Lu Guarnier, Ed Smith, Sal Faillace

3. “I Want My Avis” Prod Co: PK&A | Prod: Hal Hoffer

Designer: Mordi Gersteion | Animator: Jack Dazzo

4

4  5

5  6

6

4. “Water Follies” Sponsor: Denver Water Dept | Prod/Designer: Stan Phillips

5. “Ou Hound” CTW | Prod/Dir/Anim: John Strawbridge

6. “French T-Shirts” Bloomingdales | John Gati Film Effects

7

7  8

8

7. “Carton Graphics” 7-up | Goldscholl Associates

Designer: Morton Goldscholl Dick Greenberg

8. “No More Puckers” Yoplait Yogurt | PK&A producer: Sid Horn

Director: Phil Kimmelman | Designer: Bill Peckmann | Animator: Lu Guarnier

Leonard Maltin teaches the history of animation at the New School for Social Research, New York City, and is author of The Disney Films, among other movie books. He is currently guest programmer for the Museum of Modem Art’s “Salute to Film Comedy.”

Articles on Animation &Bill Peckmann &Illustration &Layout & Design 09 Mar 2010 08:42 am

Jack Davis @ PKA

- The esteemed illustrator/cartoonist, Jack Davis, did some brilliant art and design work for animation when working for Phil Kimmelman and Ass. Bill Peckman sent me the following article from Squa Tront magazine, and he added a couple of illustrations Davis did for PK&A.

Here’s the article:

1

1(click any image to enlarge.)

Pages 2 & 3 made a double page spread that looked like this.

I’ve split it apart so the images would be larger in thumbnails.

Some characters Davis did for a “Mrs. Smith Pies” ad.

All of the characters should be holding the product in hand.

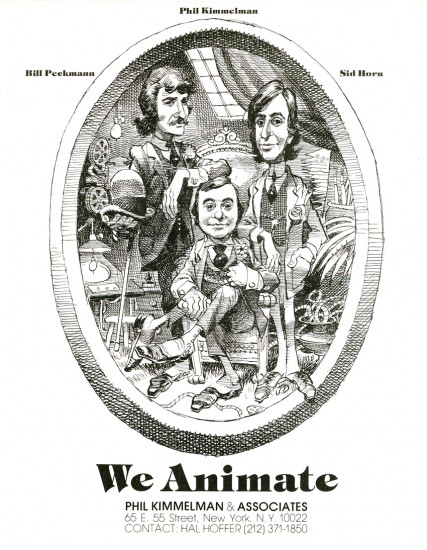

And, of course, the notable caricature by Davis of

Phil Kimmelman and his Associates for their print ad.

(As taken from the Funnyworld issue #18 – PK&A

regularly supported Mike Barrier’s magazine with their ads

Articles on Animation &Bill Peckmann &Layout & Design 04 Mar 2010 09:04 am

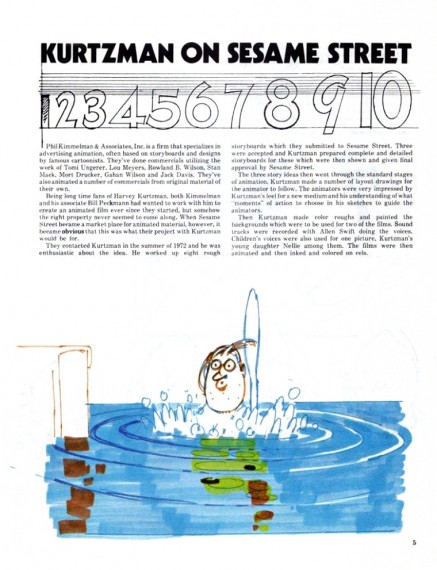

Kurtzman on Ses St

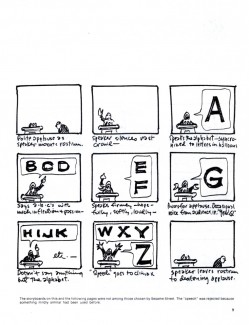

- In the old days, before Sesame Street stooped to working with softward developers to get low to free budget animation for their shows, there was an era of dignity on Sesame Corner. Animators were seen as artists and treated that way. Lots of Independent film makers were employed to create design and execute brilliant little animated pieces for the show. They created the hidden gems that made the show glow and helped support the excellent muppetwork of Jim Henson and gang.

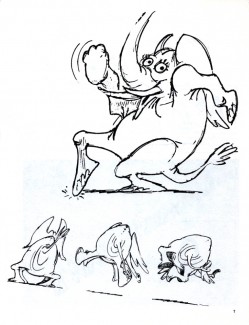

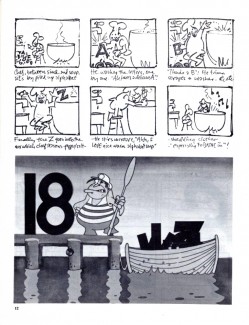

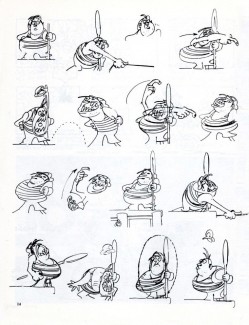

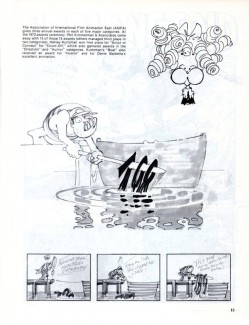

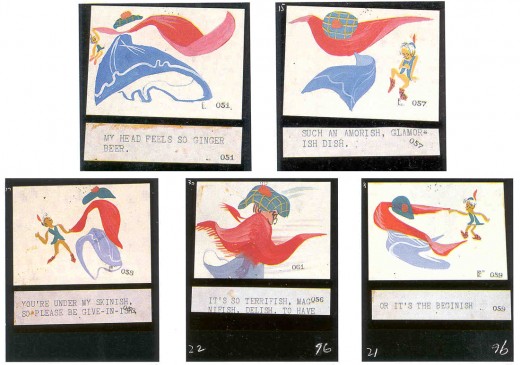

The magazine Squa Tront, issue No. 5, features an article about 8 Sesame Street films that were designed and planned by Harvey Kurtzman for Phil Kimmelman and Associates. Thanks to Bill Peckmann, here’s that article.

1

1(Click any image to enlarge.)

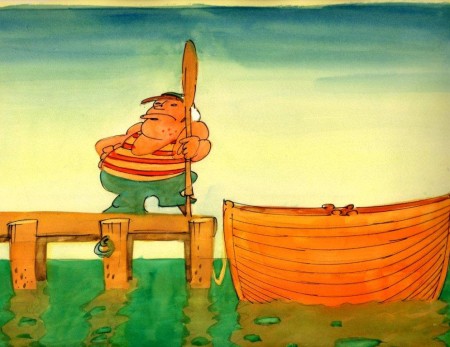

An image Harvey Kurtzman drew for his Sesame Street film, “Boat”.

Articles on Animation &Hubley 25 Feb 2010 06:40 am

Finian’s Rainbow – alt

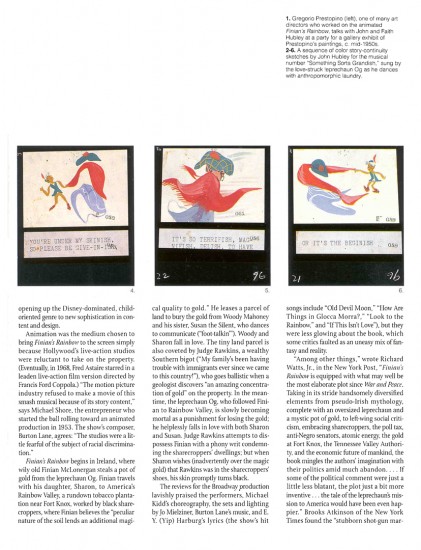

Yesterday I posted this very same article by giving the PRINT Magazine layout. Today I offer an alternate version, since I think it’s an important piece, wherein the text would be html and the illustrations could be posted larger. Hence, I’ve decided to post it twice, for whatever that’s worth. At least it allows me to keep it running for second day.

.

.

by John Canemaker

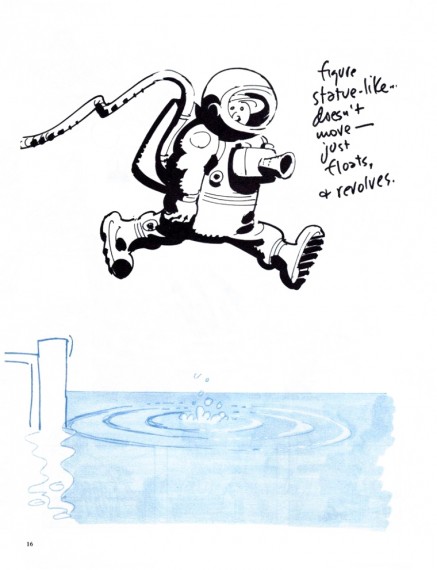

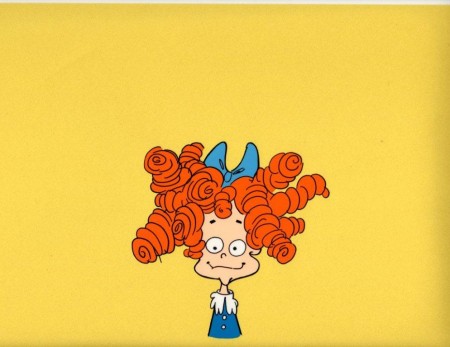

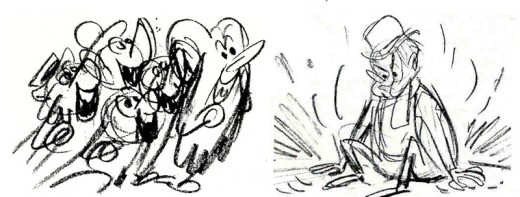

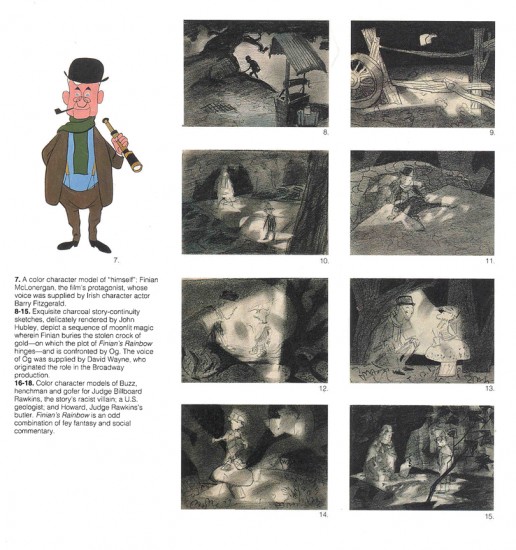

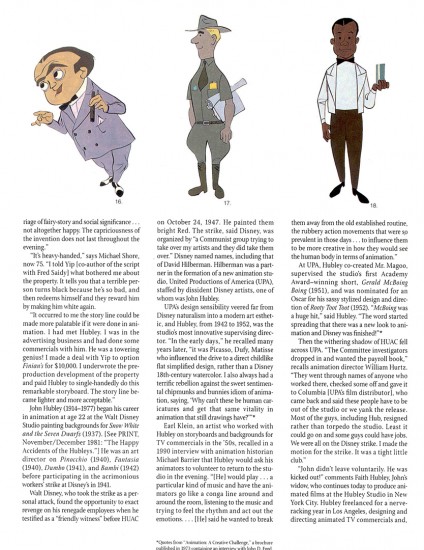

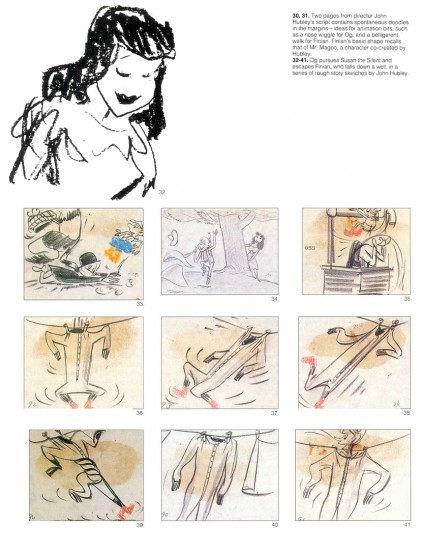

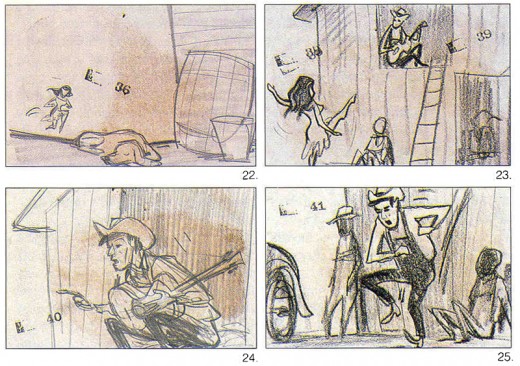

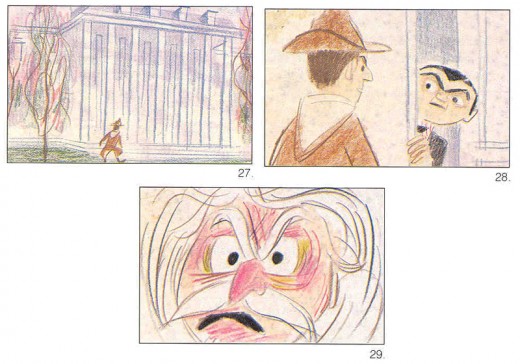

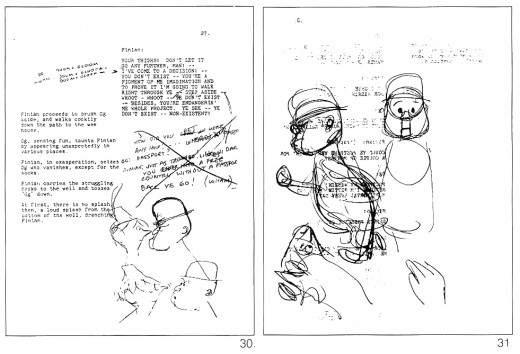

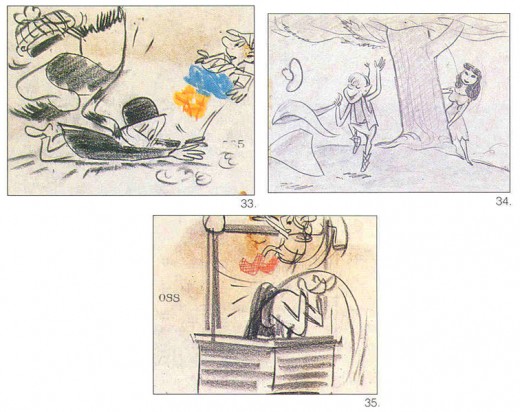

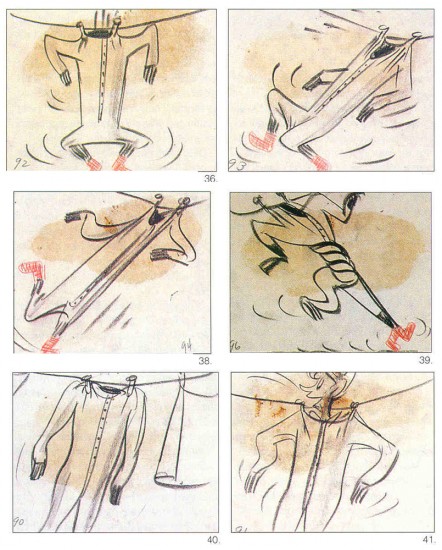

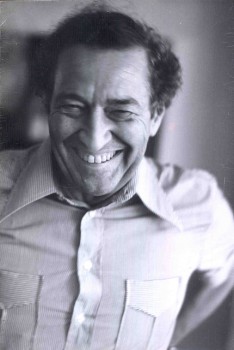

Animation innovator, John Hubley was slated to design and direct a film version of the Broadway hit, Finian’s Rainbow. But this was the fearful 50s and the witch-hunting zeal fo the time doomed the project. All that remains are 400 storyboard sketches which recently surfaced and are sampled here.

.

On January 10, 1947, the musical Finian’s Rainbow opened on Broadway to rave reviews, precipitating a successful run of 725 performances. In the fall of that same year, the U.S. Congress-approved House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) began a long-running show of its own: the official sanctioning of an “Inquiry into Hollywood Communism.”

On January 10, 1947, the musical Finian’s Rainbow opened on Broadway to rave reviews, precipitating a successful run of 725 performances. In the fall of that same year, the U.S. Congress-approved House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) began a long-running show of its own: the official sanctioning of an “Inquiry into Hollywood Communism.”