Category ArchiveArticles on Animation

Articles on Animation 24 Jan 2009 09:40 am

Scrapbook Beanies

I recently wrote about the scrapbook I had as a child, and I shared a couple of mangled pages I had which represented the debut of The Bullwinkle Show.

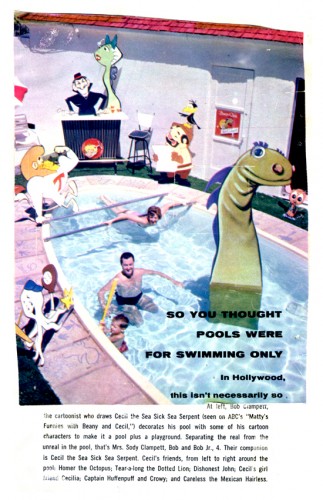

The pointless memorabilia continues with two pages I’ve saved about the debut of The Beany & Cecil Show. I don’t for the life of me know what “Matty’s Funday Funnies” was supposed to be, but I remember their using this title for something. I believe The Bugs Bunny Show followed Beany & Cecil on Tuesday nights for a very short time, otherwise B&C was a Saturday morning show.

(Click the following images to enlarge.)

A small magazine ad I’d found.

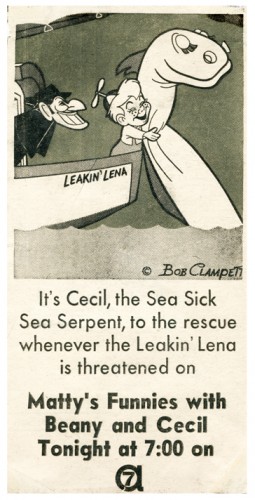

And this wacky one-page piece appeared in TV Guide.

Wasn’t TV Guide a very different magazine once-upon-a-time!

That’s about all there was for ads for this show.

Animation &Articles on Animation 20 Jan 2009 08:50 am

Obama, Borge, Babbitt, Bunin

My favorite post on the subject comes from Tom Sito‘s blog –

as might have been expected.

_______________________________

- I recently received an email from Borge Ring, and thought I’d share its contents with you:

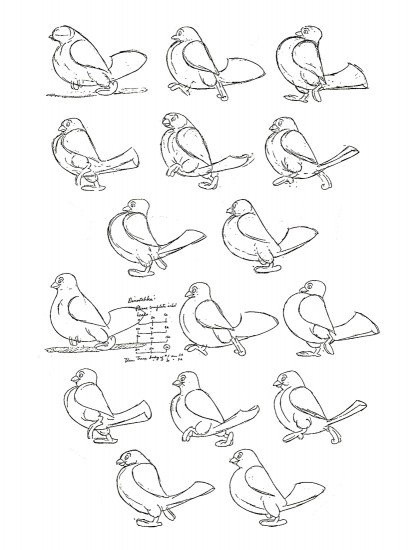

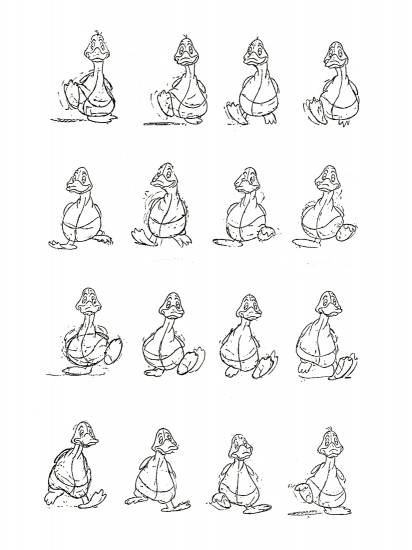

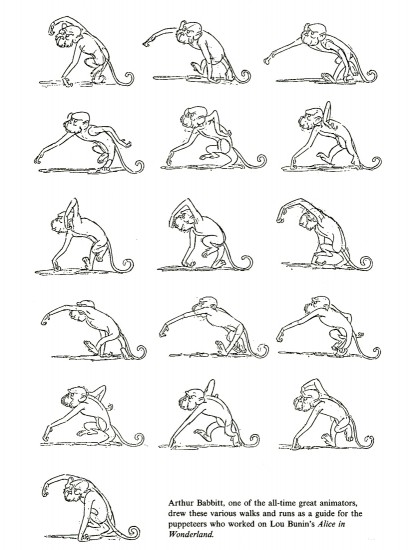

- Back in the sixties I pumped Lou Bunin at Annecy for knowledge about Art Babbitt – “My worlds best animator” at the time – whom I had never met”.

Bunin was friendly and praised Art’s animation for Bunin’s own puppet film about “Alice in Wonderland” but added:

“One thing about him surprised me”,

“What”?

“That he was”such a poor draftsman”

Art animated his scenes on paper for the puppet animator to follow.

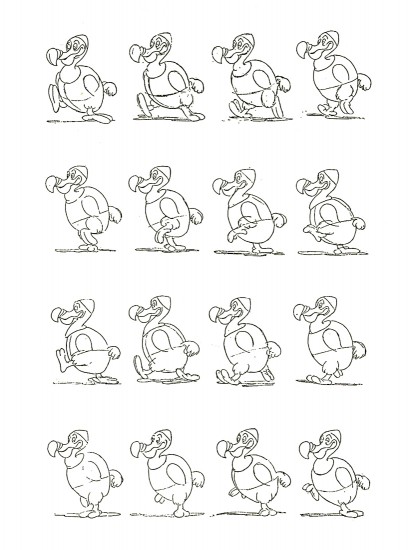

Years later I saw a scene from Bunin’s Alice of the rabbit walking up to a door and knocking.

It reeks of Babbitt.

Given this comment, I think it’d be appropriate to post these pages from Shamus Culhane’s book, Animation, From Script to Screen.”

The book includes an enormous wealth of other animation referential material and is a must-own for animation fans. I’d posted two of these two years ago.

(Click any image to enlarge.)

It’s remarkable that Babbitt was animating for Lou Buinin’s Alice at the very same time his former employer, Disney, was doing their version of the same book. Both films were released almost simultaneously.

Disney, at one point, took Bunin to court trying to suppress his Alice, but the judge sided with Bunin. The material was in public domain.

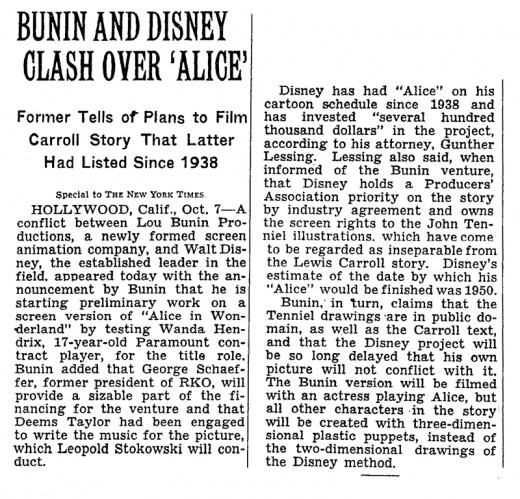

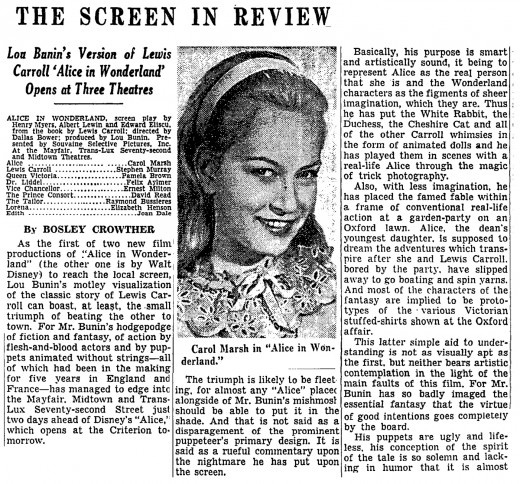

Here’s the review for Lou Bunin’s film:

Articles on Animation 16 Jan 2009 09:42 am

NY Makes it Big

- For as long as I can remember, we, in NY, have been told that the big studio is returning. Again and again we hear that lots of big projects are coming, and we’ll all have to gear up for the glory days. I saw this with Raggedy Ann & Andy; I heard this with Shamus Culhane studio’s Noah’s Ark series of 1/2 hours (before he skipped town to do them in Italy.) It was obviously happening with the advent of Doug, and then MTV, or Courage the Cowardly Dog, or whatever.

- For as long as I can remember, we, in NY, have been told that the big studio is returning. Again and again we hear that lots of big projects are coming, and we’ll all have to gear up for the glory days. I saw this with Raggedy Ann & Andy; I heard this with Shamus Culhane studio’s Noah’s Ark series of 1/2 hours (before he skipped town to do them in Italy.) It was obviously happening with the advent of Doug, and then MTV, or Courage the Cowardly Dog, or whatever.

It always seems to get back to a few smallish studios (like mine) doing individual work. That’s jsut the way it is.

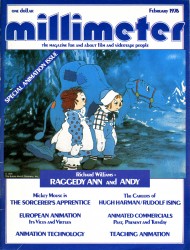

Here’s an article John Canemaker wrote for Millimeter magazine back in January 1981 (a year after I’d formed my studio.)

Return of “Long” Cartoons

by John Canemaker

Recently, New York’s animation industry has been enjoying the flattering attention of the television networks in the area of TV specials and series. Last year, three animated prime-time specials and one Saturday morning series (live-action with animated segments) were produced in the Big Apple. With three specials currently on the drawing boards at one studio, and proposals for “longer” shows being prepared by several other local houses, it appears the East Coast, particularly New York City, is witnessing a new and healthy growth in television cartoon production.

Recently, New York’s animation industry has been enjoying the flattering attention of the television networks in the area of TV specials and series. Last year, three animated prime-time specials and one Saturday morning series (live-action with animated segments) were produced in the Big Apple. With three specials currently on the drawing boards at one studio, and proposals for “longer” shows being prepared by several other local houses, it appears the East Coast, particularly New York City, is witnessing a new and healthy growth in television cartoon production.

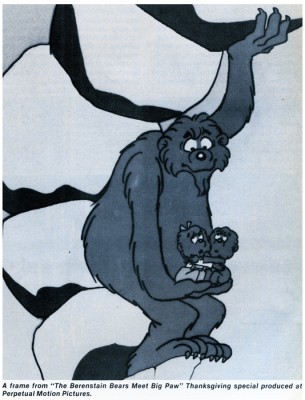

Busiest and one of the largest of the New York studios is 12-year-old Perpetual Motion Pictures, whose 1979 half-hour NBC special, “The Berenstain Bears’ Christmas Tree,” was the fifth highest rated out of 70 specials that year. The show’s success led to 1980′s “The Berenstain Bears Meet Big Paw,” aired during the Thanksgiving holiday, and a repeat of the Christmas show. This spring will see “The Berenstain Bears’ Easter Surprise” and in 1982, “The Berenstain Bears’ Comic Valentine.” In addition, Perpetual Motion is producing a special which may develop into a series, “Strawberry Shortcake in Big Apple City,” as well as its usual 60 to 70 commercials each year.

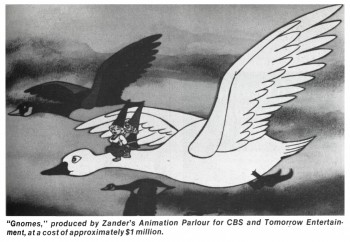

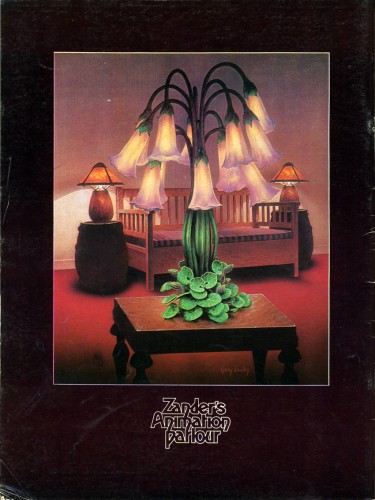

Zander’s Animation Parlour, which occupies two floors in midtown Manhattan and (as its ads say) has been “keeping the nicest company for 10 years,” managed to produce its annual load of commercials (close to 100) while producing the hour-long special, “Gnomes, “based on the best-selling picture book, for CBS/Tomorrow Entertainment.

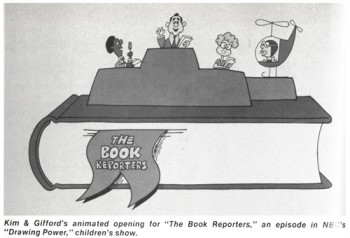

The well-established Kim & Gifford Productions Inc. also completed a full complement of titles and commercials while producing the animation for the NBC kidvid series, “Drawing Power,” produced by the creative team of George Newall and Tom Yohe. “Drawing Power,” the only new entry in Children’s Programming on NBC’s line-up of Saturday daytime programs last fall, was Newall and Yohe’s first series, although they previously produced “Schoolhouse Rock” cartoon inserts for ABC and “Metric Marvels” for NBC.

Exploring the significance of increased production

Buzz Potamkin is the 35-year-old president of Perpetual Motion Pictures. He is fond of quoting Pasteur’s, “Chance favors the mind that is prepared” to explain his studio’s dominance in the production of East Coast cartoon specials. “My partner, Hal Silvermintz, and I decided back in the early ’70s that we wanted to get into the programming area. So when opportunities arose, we took advantage of them.” Perpetual produced animated segments throughout the last decade for NBC’s “First Tuesday,” “Grandstand” and “Weekend,” among other shows.

Potamkin acknowledges a “strong negative reaction against New York City about 10, 15 years ago” on the part of TV programmers. “First, the rise of the TV commercial industry in New York required a different production flow than animated series produced on the West Coast. From a production point of view, more care than is necessary is put into a commercial. The best people went into commercials because the money was good and that was the market available in New York City. There were a few shows done in New York 10 or 12 years ago, but they were not done well—bad scripts, the wrong people working on them, not enough money, wrong concepts. And because there were so few of them done in New York, it became axiomatic that if you do it in New York, it’s going to be bad.

“Secondly,” continues Potamkin, “Hanna-Barbera had discovered a way to produce animation less expensively. That spread like wild-fire through the West Coast, so the West was being set up to produce less expensive, longer animation, and the East Coast to produce short-form, more expensive animation. And the labor pool followed that. We still have a local labor pool of perhaps 300 people as compared to 2500 people on the Coast.”

Jack Zander, who started in the animation business in 1931, recalls network negativity about the smaller New York talent pool. “A lot of people said you can’t make a long film in New York because there are not enough good animators. I said that’s not true!”

Potamkin feels the turning point in this attitude came about three years ago. “The West Coast,” he explains, “became overloaded. With the networks pushing back their pick-up dates for Saturday morning to such an extent, for that six-month period that there was work on the West Coast, you literally couldn’t fit a special in anywhere.”

Network producers began to compare the quality of East and West Coast animation, and as Zander points out, “some commercial clients expressed the opinion that the California group of animators has been working so long on Saturday morning stuff that all their animation looks alike.”

Network producers began to compare the quality of East and West Coast animation, and as Zander points out, “some commercial clients expressed the opinion that the California group of animators has been working so long on Saturday morning stuff that all their animation looks alike.”

Potamkin agrees: “With the tremendous footage requirements per week, a lot of very good West Coast animators forgot how to animate. They have difficulty getting back into fuller animation. The networks became aware of this as their specials tended to drop off in quality level.”

“New York animation,” begins Tom Yohe of “Drawing Power,” is just crisper. There is something about the formula look to Saturday morning animation done’on the West Coast—a tendency on the Coast to take a budget and figure if you have so much a minute, that comes out to three drawings a second, or whatever. I think budgets are utilized in a much more thoughtful way by New York animators, like Kim & Gifford’s Al Eugster. Here you have a scene of limited animation or a pan across something, then in another scene you heavy-up the animation. So the overall feeling is more properly paced and gives you a feeling of fuller animation than you get from the formula stuff coming out of most West Coast studios.” I Lew Gifford adds, “There’s plenty of I talent around New York. Often East Coast animators go west for work. I can see the West Coast animators coming here under the right circumstances.”

More studios available.

Another factor in New York’s favor is I the current availability of New York studios with the physical space and personnel necessary for the production of longer films. Zander cites “relatively cheaper costs in L.A. in terms of film footage and work space. And people at the networks are impressed by the space in L.A. Big rooms with lots of people sitting in them—it is important.” Potamkin agrees. “For the first time in 10 years,” he says, “two studios grew up in New York, Perpetual and Zander’s, that were large enough for someone to say, ‘we can trust them with a project this size.’ We’re not four guys sitting in an office somewhere.”

“Perpetual was being forced to consider having to relocate its studio out of New York because of the difficulty in finding a suitable studio area,” comments Nancy Littlefield, head of the New York City Mayor’s Office of Motion Pictures and Television. Potamkin acknowledges that the City’s support was especially helpful “when it came to negotiations over the space—having a couple of people from the City call the landlord and say we don’t want you to lose money, but we really want these people to stay here.” Perpetual moved into its new 11,000-foot space last June with a 10-year lease and Potamkin adds, “We intend to stay here.”

Under Potamkin’s supervision, Perpetual’s “Big Paw” special required one board and track director, one animation and layout director, five animators, six assistant animators, six in-betweeners, a production coordinator, three checkers, two Xerox operators, 20 opaquers, a camera service and so on, through other divisions in the studio’s staff of 67 full-time employees.

Zander’s Animation Parlour normally staffs about 25, plus freelancers, but hired about 85 for the “Gnomes” special. Lew Gifford of Kim & Gifford estimates he has a dozen on staff, but added six or seven animators when his company was preparing the animation for the Saturday morning series, “Drawing Power.” “We have been successful,” he points out, “in not raising the amount of space we have. For a six-to-eight-month run, you don’t want to raise your space.” He notes that the Astoria studio facility in the New York borough of Queens “has space for both live action and animation, and that’s a possible space factor for expansion of facilities.”

The bulk of the preparation for “Drawing Power” came from its two energetic young producers, George Newall and Tom Yohe. “We had a tight schedule,” recalls Yohe. “We got a very late pick-up at the end of April for an October 11 premiere.” Newall adds, “When we got the order, we just started working night and day. Never having done it before, and not even sure we could do it, we worked a lot harder than we might have.”

The informational series takes place, interestingly enough, inside an animation studio. “The show needed animation to be competitive on Saturday morning,” Yohe explains. “We were very lucky in regard to the crippling SAG strike; in six or eight weeks we had all our tracks written and recorded and to the animators before July, so we beat the strike. The live action was under an AFTRA contract; we shot tape during daytime, so we were able to stay in production right through the summer when a lot of guys had to close down.”

Yohe figures that one reason they were able to produce “Drawing Power” without taking on a large staff “is the segments of animation are short—none lasts more than 45 seconds.” The cost of the animation was “in the $7000 per minute range, without tracks.” There were 12 shows containing 10 minutes of live action, with about 14 minutes of animation per show at a cost of about $150,000 per show, or “equivalent to what Hanna-Barbera gets.”

No immediate profit

The half-hour specials of Perpetual Motion are budgeted roughly in the $400,000 range, according to Potamkin. “But costs are inching up now to about $450,000 per. All network shows have relatively me same budget because that is what is available to be spent. Frequently that’s more than the networks are willing to spend! Making specials is not as immediately profit-oriented as making commercials. With commercials, you know what the profit is going to be. With shows, that is not true. The profit doesn’t exist up front. The chances of someone paying $750,000 for a half-hour special in today’s market is very, very unlikely. One has to accept the reality that you’re going to make less money. A lot of people in this business of animated commercials don’t want to accept this.”

Zander’s “Gnomes” had costs that “hovered around one million bucks, which,” says Zander, “is a lot of money for an hour show. The standard rate for an hour special is $750,000, but CBS and Tomorrow Entertainment threw in some extra money and brought it up to the point where we could do something with it.” The 48-minute, 16-second special took almost two and a half years to see completion. Explains Zander, “It took a year or two to get a good story. The script had to be redone. After that, there was still a year’s work in animating.”

Zander’s “Gnomes” had costs that “hovered around one million bucks, which,” says Zander, “is a lot of money for an hour show. The standard rate for an hour special is $750,000, but CBS and Tomorrow Entertainment threw in some extra money and brought it up to the point where we could do something with it.” The 48-minute, 16-second special took almost two and a half years to see completion. Explains Zander, “It took a year or two to get a good story. The script had to be redone. After that, there was still a year’s work in animating.”

Zander believes that for half-hour specials, “money is not too hard to come by if you find a good property.” But he speaks candidly about the dangers of “animators almost pricing ourselves out of business. We’ve just signed a new contract with the union [Motion Picture Screen Cartoonists, Local 841]. Really, the wages are going up pretty steep. Minimum for an animator is close to $550 per week, and categories below that have come up, too, like inkers, painters getting about $250 per week.

“One time,” recalls Zander, “we had a separate contract for long films. Now in my mind, if you guarantee a person work for a year at $400 a week or whatever, that’s better than working catch-as-catch-can for $600. And it makes it more appetizing for somebody to invest in a film. I think,” continues Zander, “applying commercial rates to feature films is not going to help us. We do a half-minute commercial now for about $20,000. Multiply that by 30 minutes. That makes animation an awfully expensive medium! If we are now seriously considering bringing longer films back to New York, and they are considering us, we’re going to have to work out a different contract.”

Interest in longer films

Indications are that the opportunities to do longer films in New York will continue to occur. “I think the reputation of the City has shifted,” claims Potamkin. “Doors closed to us are now open. People are more willing to talk to us now. I’m sure Jack (Zander) is having the same experience. And they’re not just talking to us as a production office, where work is shipped toL.A., Japan, Europe, but produced right here in NeW York. I know the union is very Happy abouht, lopuhtmildly.”

“The day after ‘Gnomes’ was shown,” recalls Zander, “I got three phone calls from people who have properties they want made into specials. I’m interested, despite the hard work, because, first, it was a lot of fun. Very gratifying, too. I personally put in time on weekends. I enjoyed the challenge and my staff did, too!”

“I don’t know if it’s a trend,” points out Yohe. “I think the networks are happy with the animation they’re getting from us. We’d like to do an animated special at this point. We have things sitting on desks at the three networks, but it’s so unpredictable. They do have an interest in having production done here. It’s also very nice for the children’s programming people here to be able to pop in and look at things without a trip to the Coast.” Newall adds, “We’ve been in business for three years and have yet to set foot in California. And now that the air fares are going up, we’re even less likely to go!”

Lew Gifford finds that “there’s a lot more fun in doing things that you can continue for a long period of time, providing they’re of high quality. There is still a great deal of fun, in solving problems for advertising agencies, but it’s not the same thing as doing an entertainment.

“In the commercials business, you’re lucky if you can look two months ahead. The significant difference,” Potamkin states, “is that instead of being tactical planners where we plug up the dikes and the anxiety about how long the work is going to last, now we can get into strategic things—two we’re finishing, roll over, do one more, plus commercials. What should we do after that? Who should we be talking to? How do we want to bring our younger people along, which we’ve always had a commitment to doing?”

Potamkin has every right to feel confident and secure about his studio’s future in animation produced in New York. “For the first time,” he states “since Hal Silvermintz and I opened this studio 12. years ago, we can look a year ahead and know—bottom line minimum—the work that we have. For a year,” he emphasizes.

Animation Artifacts &Articles on Animation &Commentary 15 Jan 2009 08:52 am

Scrapbook Bullwinkle

- When I was young, there was little in print about animation. So I kept my eyes open for every newspaper or magazine piece I could find about the subject and I put it in a scrapbook I kept.

- When I was young, there was little in print about animation. So I kept my eyes open for every newspaper or magazine piece I could find about the subject and I put it in a scrapbook I kept.

The Flintstones debut, the opening of 101 Dalmatians, Mr. Magoos 1001 Arabian Nights, Gay Purr-ee, Dick Tracy, The Wonderful World of Color were all projects that generated some publicity – not like you see today, but some. I collected all I could find.

That scrapbook is in storage somewhere, and I won’t find it for a while. However, I do have a couple of pages that seem to have fallen out. This covers the premiere of The Bullwinkle Show on NBC – just prior to Disney’s World of Color show. None of it is pertinent to anything, and all of it is in lousy condition. Regardless, here are a few pieces including the only review I could find – from the NYDaily News. Remember there was no internet, no way to research papers outside of the ones your parents brought home or you could find in the library. This was all material that I had access to.

In advance, I apologize for the condition of these images. They were well read within a roughly assembled scrap book, and they have seen the battlefield of use.

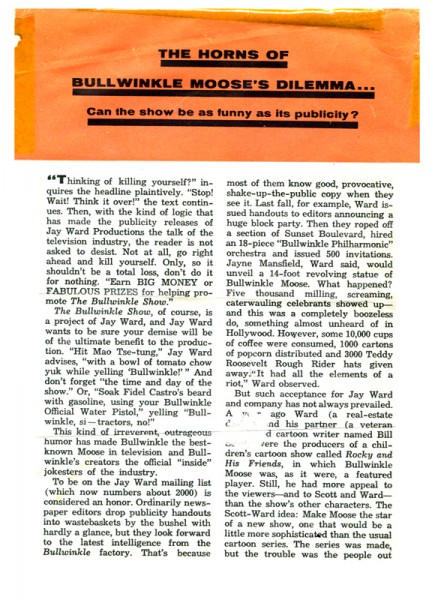

This article (above & below) comes from an issue of TVGuide just prior to the start of The Bullwinkle Show in primetime. Jay Ward fashioned a big and entertaining publicity campaign to get his show on TV and to keep it there. The article discusses this PR aspect of the show.

You can get more information from Keith Scott‘s excellent book,

The Moose That Roared.

(Click any image to enlarge to a readable size.)

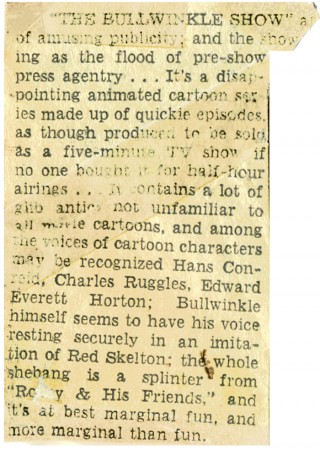

This negative review came from The NYDaily News.

Most of it is legible here.

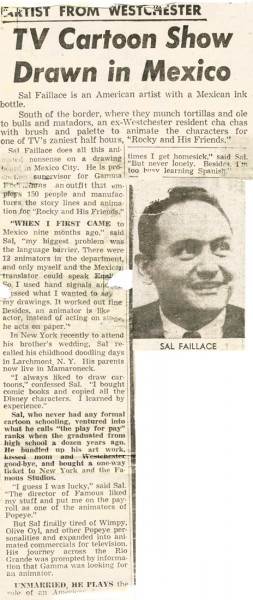

The gold, for me, came one Sunday in the Westchester edition of The Daily News.

My family was on its regular Sunday summer outing at a New Jersey beach. I came upon the article and spent most of the day reading and rereading it in the sun. I didn’t realize that Sal Faillace was just a local boy with a local news story.

Years later, I got to assist Sal at Phil Kimmelman‘s PK&A studio. I can remember that he animated a bouncing basketball with NO stretch or squash. A hard circle moving “bouncing” around the screen. I was disillusioned in Sal’s work until I actually saw it on film. He really had somehow captured the weight and feel of the basketball without the obvious approach most animators – including myself – would have taken.

I’m sorry I didn’t really spend much time talking with him or asking him about his work at Gamma Productions in Mexico.

Articles on Animation &Puppet Animation &Trnka 30 Dec 2008 09:11 am

Trnka – 79

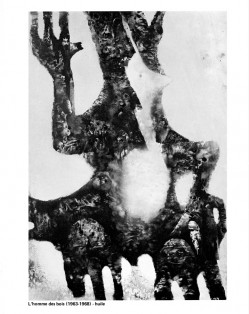

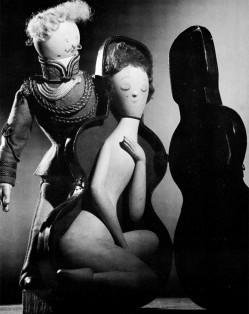

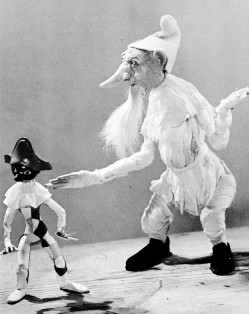

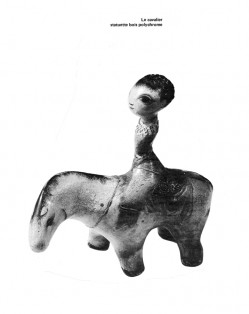

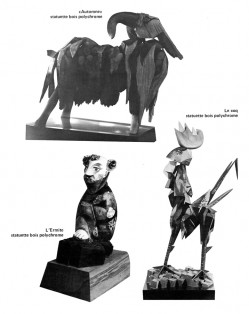

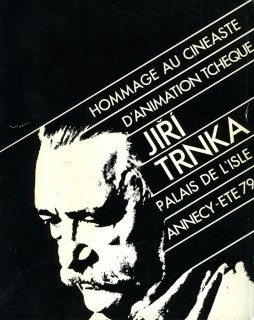

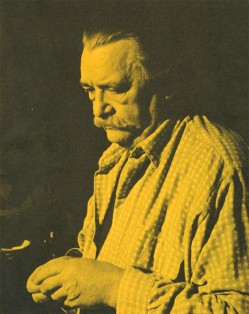

- In 1979, the Annecy animation festival celebrated the work of Jiri Trnka.

- In 1979, the Annecy animation festival celebrated the work of Jiri Trnka.

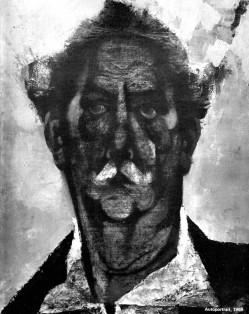

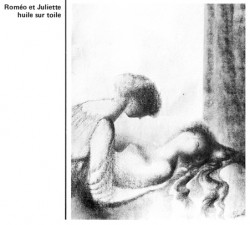

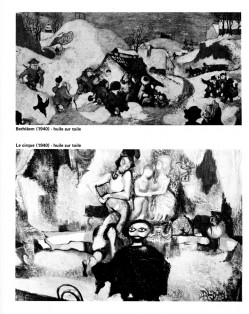

They produced a companion booklet for the film program and art exhibition. I’d long ago managed to get my hands on a copy of this booklet and am posting it here for any Trnka fanatics out there.

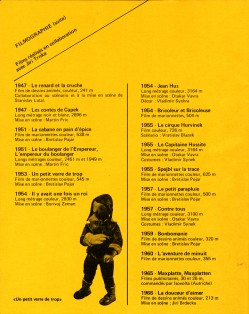

The artwork in the booklet is somewhat hard to find elsewhere, and the stills from the films are quite nicely chosen. There’s also a comprehensive biography and filmography that was included on very orange paper stock.

There aren’t too many chances to see the films anymore (other than the scattered, poor-quality YouTube pieces) except for the dvd produced by Jon Snyder. The Puppet Films of Jiri Trnka

The booklet is in French, but that shouldn’t be too much of a problem; it’s fairly self-explanatory.

(Click any image to enlarge.)

Articles on Animation &Hubley &UPA 19 Dec 2008 09:07 am

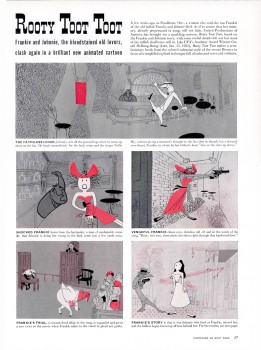

Retreads – Rooty Toot Toot

(Click any image to enlarge to a readable size.)

- In 2006 I posted this LIFE Magazine story on Rooty Toot Toot from a March, 1952 issue. They obviously enjoyed the UPA films back then, and luckily for us they posted it on something concrete – like paper.

My reason for posting it, originally, was a UPA celebration that was being screened at the Egyptian Theater in Hollywood. That’s long past, now, but Rooty Toot Toot lives on. I think of this as one of THE greatest animated films of all time. I doubt a month goes by without my watching it anew for inspiration.

The story goes that Stephen Bosustow was furious with John Hubley for taking so long on the storyboard and development of this short. Hubley eventually locked himself in his office and finished the prep to his own satisfaction. That’s how they finished the film. Needless to say, it went over budget.

The 1951 film obviously had world wide resonance. The story of a murder as told from different perspectives took the idea from the 1950 Kurosawa film Rashomon, wherein several people around a campfire tell different versions of a story. Of course, the premise dates all the way back to Chaucer, but there weren’t many film makers doing it at the time. Interestingly enough, Rooty Toot Toot was nominated for an Oscar the same year that Rashomon won a special award for Best Foreign Language film.

After seeing the short for the first time at a special UPA program in 1974, when I was working for the Hubley Studio, I told John that I’d just seen it and was blown away. He gave a short smile, turned and walked out of the room. He obviously didn’t want to talk about it. I guess the thorny years of the McCarthy era forced him to deny his own work of genius from a hellish period.

Just prior to the Egyptian screening, Amid Amidi posted some UPA crew photos on the Cartoon Modern site.

Amid has also posted some great art from the film on that same Cartoon Modern site.

part 1 part 2 part 3 part 4

Articles on Animation 18 Dec 2008 09:07 am

Spots – 1976

- Back in 1976 John Canemaker asked if I was interested in writing a piece on commercial studios for Millimeter Magazine. I was interested and took the job (while at the same time working at the Raggedy Ann studio.)

- Back in 1976 John Canemaker asked if I was interested in writing a piece on commercial studios for Millimeter Magazine. I was interested and took the job (while at the same time working at the Raggedy Ann studio.)

I found that commercial production was on a downswing and theatrical production up, keeping a lot of the smaller studios operating. That became my thesis for the piece, and I got in trouble for speaking my mind. One producer I praised said I was on his “s##t list” and I didn’t have to bother applying at his studio for a job. Since I had never sought work in his company, I found the thought amusing but was still confused that he’d found my article bothersome.

Looking back on the article now, I see that it was much ado about nothing; the article is and was harmless. However, it does give an overview of the commercial world – particularly in New York. Hence, I thought I’d entertain myself by posting it.

As much as 20 years ago, the animated commercial was fast becoming a viable art form. Bert and Harry Piels and Marky Maypo had already entered our lives via the television spot, and audiences waited through many an hour of mediocre TV presentations to be entertained by such characters in their one-minute commercial messages.

As much as 20 years ago, the animated commercial was fast becoming a viable art form. Bert and Harry Piels and Marky Maypo had already entered our lives via the television spot, and audiences waited through many an hour of mediocre TV presentations to be entertained by such characters in their one-minute commercial messages.

Commercial studios competed with one another to produce higher quality productions and more popular and entertaining films. The studios were major ones employing up to 75 people to produce their work. UPA, Academy, Storyboard, Pelican, and Elektra all existed with creativity and design strongly apparent in their storyboards and continuing right through to their finished product.

There was much experimentation in design and approach. The public readily accepted the new styles which they rarely saw or sought in theatres. (Even the trend setting UFA films of the early 50′s didn’t really receive audience acceptance till the arrival of these commercials.) The workers and producers alike took pride in their commercial product, and the results showed in the finished films.

Needless to say, many things have happened in the past 20 years. TV animation took a turn for the worse. Saturday morning, which had been filled with Mighty Mouse, Winky Dink, and Ruff and Ready filtered into a heyday for revitalized prehistoric monsters sliding across the screen with a superhero or two or seven talking for endless hours. Mind you, nothing moved but the sliding monsters and their mouths, but the networks bought it.

The animated commercial also took a nose dive. Individuals from these large studios began setting up their own one- or two-man studios. Their overhead was lower and, naturally, could come up with a lower bid for the commercials. The larger studios couldn’t compete with them and, as a result, became smaller. Dozens of people were thrown out of work. They were made to fight for freelance work from these small studios, change their careers midstream, or retire from their art. Many a good animator, assistant animator, inker or background artist was lost to the system. The result of underbidding was that the budgets never increased while the cost of animation became prohibitively expensive. The producers were forced to find new methods of presentation to stay alive in the commercial market.

The “classic” commercial became a rarity rather than the norm. Even the time allotted the producer to relay the message was reduced. The spots went from 60 seconds to 30 or even 20. The commercials, like Saturday morning TV, became limited in imagination, if not in animation. The agencies took charge of the writing for all campaigns, and more often than not creativity was lacking by the time the producer-had received the spot. There was too much concern for the statistics of the testing and too little concern for what was entertaining as well as selling. When the storyboard was lacking in creativity, even the most conscientious producer was able to do little more than contribute good production values to the finished spot. The spark had been eclipsed.

It is common knowledge that the film business, particularly animation, has had an inordinately poor first half of 1975. Many an animator, unable to find work at any studio, was ready to move for the sun and retire. There was just too little work on the boards. Agencies were looking for live action; a large number of spots were being sent out of the U.S., and a large number of non-union people were competing with and undercutting the established producers (the agencies didn’t seem to mind the cut in production values if they could get the spots done less expensively). With all of these problems apparent, it seemed difficult to imagine how a production house could, indeed, remain in operation.

Toward mid-year, a number of theatricals began to creep into production: THE METAMORPHOSIS brought a new company, San Rio, into being, while RAGGEDYANN AND ANDY brought a theatrical producer, Lester Osterman, into animation; Ralph Bakshi continued his films, COONSKIN, HEY GOOD LOOK-IN’, and THE WAR WIZARDS, while Alexander Schure brought his college, New York Institute of Technology, into production of the feature TUBBY THE TUBA; a third Charlie Brown feature began production at Bill Melendez’ studio, while the 24th feature, THE RESCUERS, began production at the Disney studio. Business in animation was returning to the theatres, just when it seemed that the animated commercial was hardly capable of supporting any studio.

The Hubley Studio, owned and operated by John and Faith Hubley, was formed from Storyboard, Inc., the company set up by the Hubleys in the early 50′s after John had left UFA and he’d met Faith. Storyboard’s commercial films were unique, clever and consistently high in quality. Marky Maypo’s dialogue still exists in the minds of most of TV’s first generation of viewers. The Hubleys used the commercials to pay for their theatrical ventures. Eventually, they moved almost completely to the production of these personal, theatrical films.

The most recent of these personal films is a 90-minute TV production, produced by CBS. Everybody Rides the Carousel is based on the writings of Erik Erikson, the noted psychologist. The film shows the development of a person in a society. This is, obviously, unique material for animation, not to speak of TV animation. It will be curious to see if any effect will be made on other animated programs.

The Peanuts specials, needless to say, have had a great impact on television animation, if not on all phases of American society. Bill Melendez runs the studio that has been producing these films. His studio has been operating for the last 12 years, but, obviously, never has it been so successful. There have been two feature-length films to spin off the very successful TV specials, and now a third theatrical film is in the works. Curiously enough, the few commercials that move through the studio are Peanuts-oriented. At the moment there are two spots being produced for Japanese television starring Charles Schulz’ characters. The studio, thanks to Peanuts, is able to keep a staff of, at least, 15 people on full time.

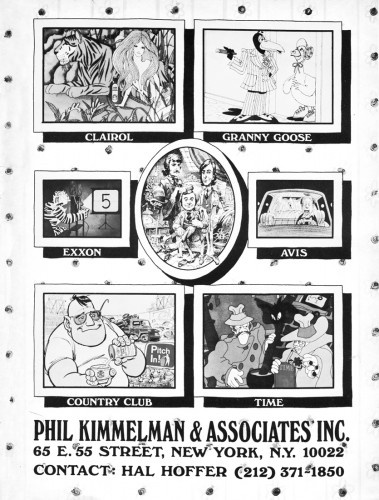

Most of the other commercial film producers are beginning to look into theatricals. Phil Kimmelman, producer and executive member of Phil Kimmelman & Associates, continued his use of noted designers (Jack Davis, Mort Drucker and Rowland Wilson, who has become an important mainstay of the studio, had designed ads and episodes of Scholastic Rock) when they commissioned Gahan Wilson to design a Halloween special for television. The prospect never passed the boarding stage, since the money ran out. They are still hoping for a backer.

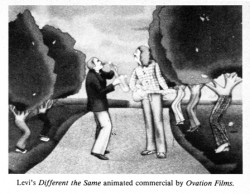

Other studios such as Zander’s Animation Parlour and Ovation, which normally produce only commercials, (Jack Zander had directed the TV feature The Man Who Hated Laughter, and Ovation is currently making a 10-minute industrial film) have said that they are interested in making theatrical films, but they want to be sure that the budgets are large enough.

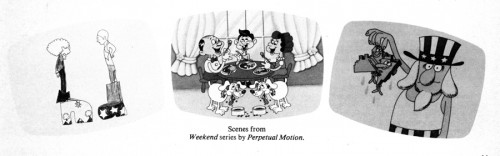

The problems involved in searching for theatrical films from the vantage point of a commercial film producer can be best illustrated by demonstrating the situation at Perpetual Motion. Studio heads Buzz Potamkin and Hal Silvermintz openly stated that they want to enter the theatrical market. They have been producing a series of low-budgeted spots for NBC’s network, late-night program Weekend. The show is aired the first Saturday of each month on NBC. Each program incorporates in its schedule one or two animated, editorial cartoons. These are usually satirical comments on some phase of the current news stories. Both producers enjoy doing these films since they’re given a freer rein than they usually have with the commercials. Stylization, story and design all combine to make miniature entertainment films for television. They would like to begin a longer film, but they want to make sure that it’ll be a project they’ll enjoy working on for the year or two it’d take to complete.

Buzz Potamkin left little doubt that he thought the animated commercial was far from dead. He stated that he expects this to be far from Perpetual’s worst year, however, if it weren’t for the Weekend spots and several jobs for NBC Sports (animated spots for Joe Garagiola’s pre-game show), the studio might have had a much poorer year. These short films allowed Perpetual to maintain a staff, however minimal.

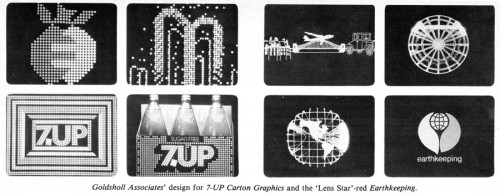

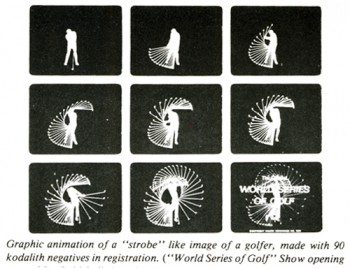

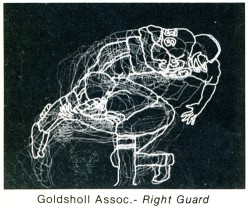

Morton and Millie Goldsholl are designers in the Chicago area who operate a studio which includes three full-time animators who are capable of table-top, stop-motion films, as well as cel animation. Morton Goldsholl states that half the studio’s film work is in longer films. They have produced a large body of work with some 12 titles listed among their experimental films. Much time is spent in experimentation, and, consequently, they have developed a “strange optical method” which is called “Lens Star.” The end result is a product which bears a resemblance to the “computer image” but, in fact, retains the warmth of the human touch. This method was used in a title to Earthkeeping, an ecology series. The 60-second title represents the beginning of life to the present ecological dilemma.

The Goldsholls seem to have touched on the best of both worlds, and perhaps this is actually what the majority of the commercial studios would like to strive for. They produce a number of commercials each year while still making the short industrial films. This has kept their studio very busy in the past two years.

Commercials, of course, have not disappeared, nor have they been as poor as this article might have led you to believe. There were a number of well-produced spots within this last year, and most of the studios can admit to a good second half of 1975. At the moment, several of the studios are at peak production.

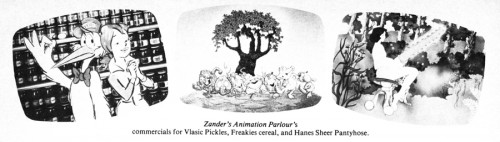

Zander’s Animation Parlour is New York’s largest commercial producing studio. They are presently able to maintain a staff of 25 people to handle their film production. Jack Zander, a long- time veteran animator, heads the studio since 1970 when his studio, Pelican, closed. A large number of specialized commercial films are produced at Zander’s. The spots for Freakies breakfast cereal, animated by Preston Blair, have achieved quite a bit of success. Each eel is a major rendering effort, being prepared with colored pencils on colored paper and pasted to the celluloid sheets. The same method of rendering was employed in the most recent Vlasic Pickle commercials and the Hanes Sheer Pantyhose ads. The studio artists combined live-action with animation successfully on the spots for Dayton’s, a department store located in Chicago, and in an ad for Texaco.

Perpetual Motion has done a spot for Baggies which they are quite proud of. The commercial was designed by Hal Silvermintz. A recent AT&T corporate spot was designed by Guy Billout and animated by Vinnie Cafarelli and Vinnie Bell. Perpetual also has recently acquired the Schickhaus commercials, and for the past year, they have produced the Hawaiian Punch commercials. With these spots, they had a somewhat interesting problem: they were given an established character and design style and told to continue the series in the same vein. They’ve been successful.

Phil Kimmelman & Associates had a slightly different problem with the Cheeto’s Mouse. They were given these spots several years back. The client had been unhappy with the results he had received from other studios. Kimmelman has had the spots ever since. Bill Peck-man, a designer at the studio and a board member of the group, stated that these spots give them a chance to explore a bit with nuances in character. Since they’ve been handling the character for a while now, they feel that they can have some fun with him.

This is all quite interesting when you realize that they have just recently begun producing a number of commercials for Piels Beer which star Bert & Harry Piels.The studio has asked to continue the line of commercials done in the 50′s by UPA. The result was several 30-second spots starring the two characters (once again voiced by Bob and Ray). Kimmelman remarked that he found himself using several of the artists who had worked on the original films (Lu Guarnier had animated the spots at UPA in the 50′s and worked on them again in the 70′s). The only difference between these commercials and the earlier ones is that these are in color.

This is all quite interesting when you realize that they have just recently begun producing a number of commercials for Piels Beer which star Bert & Harry Piels.The studio has asked to continue the line of commercials done in the 50′s by UPA. The result was several 30-second spots starring the two characters (once again voiced by Bob and Ray). Kimmelman remarked that he found himself using several of the artists who had worked on the original films (Lu Guarnier had animated the spots at UPA in the 50′s and worked on them again in the 70′s). The only difference between these commercials and the earlier ones is that these are in color.

Bajus-Jones was formed six years ago in Minneapolis by Mike Jones and Don Bajus. The main office remains in that city, where some 14 people are employed. The studio has representatives in Chicago and New York, and some production is done in New York. Their work has principally been the making of animated commercials—recent commercial productions include a spot for Phillips Petroleum, and one for GMC Truck division— but they are now at work on a pilot for a feature-length film.

Ovation is owned and operated by Jerry Lieberman, Howard Basis and Art Petricone. Their most recent pride is for a number of spots just completed for Whitman’s Chocolate. The commercials, animated by Doug Crane, are done in the style of the sampler on the box of the chocolates. The end result is an animated crewel that is quite effective. Also of interest from the studio is a Clairol Herbal Essence spot which has a live-action figure walking through an animated garden of earthly delight. This is also the studio that did the campaign for Eastern Airlines. Each commercial incorporates a great number of animated figures. The detail is staggering.

Ovation is owned and operated by Jerry Lieberman, Howard Basis and Art Petricone. Their most recent pride is for a number of spots just completed for Whitman’s Chocolate. The commercials, animated by Doug Crane, are done in the style of the sampler on the box of the chocolates. The end result is an animated crewel that is quite effective. Also of interest from the studio is a Clairol Herbal Essence spot which has a live-action figure walking through an animated garden of earthly delight. This is also the studio that did the campaign for Eastern Airlines. Each commercial incorporates a great number of animated figures. The detail is staggering.

Several studios consider themselves, basically, graphic design studios. The work of the Goldsholls was previously mentioned, though indeed, their commercial work is outstanding. A recent one for 7-Up received well-earned celebrity among TV spots. Their Gillette Right Guard ads employed rotoscoped animation within the graphics. Just recently begun were two fully animated spots for Kellogg, which Morton Goldsholl feels will be a milestone for the studio.

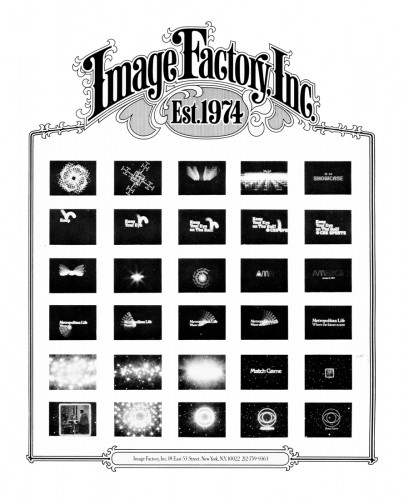

George McGinnis and Mark Howard are the proprietors of the Image Factory. The two producers are designers who would like to see greater use of design and camera in animated films. This approach is, obviously, echoed in their film production. They’ve designed and directed the introductions for the five Mobile Showcase Presentations; (this included the famed TV productions of Moon for the Misbegotten and Queen of the Stardust Ballroom.) They’ve also designed the end logo used in the Metropolitan Life Insurance campaign. They’ve produced the Fall campaign for the CBS-owned and -operated stations. The two producers have a strong interest in moving toward more wholly animated projects, and their final goal will be reached when they can successfully see the combination of animated graphics with in-depth character animation.

George McGinnis and Mark Howard are the proprietors of the Image Factory. The two producers are designers who would like to see greater use of design and camera in animated films. This approach is, obviously, echoed in their film production. They’ve designed and directed the introductions for the five Mobile Showcase Presentations; (this included the famed TV productions of Moon for the Misbegotten and Queen of the Stardust Ballroom.) They’ve also designed the end logo used in the Metropolitan Life Insurance campaign. They’ve produced the Fall campaign for the CBS-owned and -operated stations. The two producers have a strong interest in moving toward more wholly animated projects, and their final goal will be reached when they can successfully see the combination of animated graphics with in-depth character animation.

Edstan is run by Stanley Beck and Ed Feldman. They are a graphics studio which will put the designs brought to them on film. They recently produced the graphics for NBC, CBS and Metromedia’s Fall campaigns. They also produced the opening graphics for the networks’ film programs. The studio has been in operation since 1959 and has produced a large number of network titles (most of the late night movie titles were produced at Edstan.)

With the Cheeto’s mouse, Freakies’ freakies, the Hawaiian Punch character, Vlasic’s stork, and the revival of Bert and Harry, it looks auspiciously as though animated commercials are turning toward the characters to entertain us. Perhaps this will be the trend; the agencies will spend more time caring about the viewer and a lot of good animation will come across the TV sets in America.

Articles on Animation 13 Dec 2008 09:28 am

The Goldsholls

- In posting ads the other day, I found the one for the Goldscholl Associates (reposted below), a pair of animation producer/designers, Morton and Millie Goldsholl, who have been completely overlooked in this “new era.” Mort was a prominent industrial designer who turned to film and commercials working with wife, and fellow designer/director/animator, Millie.

- In posting ads the other day, I found the one for the Goldscholl Associates (reposted below), a pair of animation producer/designers, Morton and Millie Goldsholl, who have been completely overlooked in this “new era.” Mort was a prominent industrial designer who turned to film and commercials working with wife, and fellow designer/director/animator, Millie.

Trying to keep the memory alive, I went in search of any articles – even puff pieces I could find to give more info about them for those interested. I found this Millimeter Magazine article in their April 1975 issue about animation companies in Chicago. The latter half of the article was about several other Chicago companies, but my focus is on the Goldsholls.

The Loop

bu Sherry Seckel

- Historically, the first commandment of film production in and around Chicago has been that fat budgets go to the coasts and lean ones stay here. On the surface, that principle holds true for animation productions, especially in the area of commercials coming out of Chicago advertising agencies. But to say that the animation talent in

Chicago is low-budget would do an enormous disservice to the producers and clients alike, many of whom are finding unique production capabilities right in their own back yard. In addition, clients from outside the Chicago area have discovered that the diverse talent and facilities here can make production in Chicago a matter of choice, not just necessity.

Chicago is low-budget would do an enormous disservice to the producers and clients alike, many of whom are finding unique production capabilities right in their own back yard. In addition, clients from outside the Chicago area have discovered that the diverse talent and facilities here can make production in Chicago a matter of choice, not just necessity.

The most successful of such animation producers is probably Goldsholl Associates, located in the Chicago suburb of Northfield. What makes Goldsholl so attractive to national and international clients alike is their ability to take a project from conception through completion almost totally in-house.

At the top of the organization is Mort Goldsholl, whom Bob Rowe, Director of Sales, calls a true “conceptualizer.” With an extensive background in design, award-winning Goldsholl has invented an optical lens distortion technique for animation which takes a two-dimensional piece of art and, in camera, makes it appear three-dimensional. Another revolutionary technique with Gold-sholl’s stamp on it is his rotoscope animation, recently  used in Gillette commercials. Working closely with Goldsholl is his wife, Mildred, who is a producer, director, writer and editor, also with a background in design. Animation Director is Peter Dakis and Production Manager is Tom Freese, a cinema-tographer known for his fluid head method used in Hallmark commercials.

used in Gillette commercials. Working closely with Goldsholl is his wife, Mildred, who is a producer, director, writer and editor, also with a background in design. Animation Director is Peter Dakis and Production Manager is Tom Freese, a cinema-tographer known for his fluid head method used in Hallmark commercials.

Backing up the talented staff is sophisticated hardware to match. Along with a sound stage, 16mm and 35mm cameras recording equipment and editing equipment with Moviolas and a Kem is an automated Oxberry animation stand, designed by staff member Jim Logan.

After some 34 years in the business, Goldsholl Associates is firmly entrenched in its position as a consummate animation production studio. Says Bob Rowe, “Heretofore, if you needed a slick piece of animation, you had to go to the Coast or New York. We don’t have a stable of animators and painters; we want to retain our uniqueness.” Mort maintains that he does not want to be everything to everybody.

Animation Artifacts &Articles on Animation &Bill Peckmann 11 Dec 2008 08:33 am

Ads for Ad Companies

- Flipping through some old film and animation magazines, I couldn’t help but look at all the old ads for the many animation companies that were ever present and are now gone. In a way, back then, you were pleased to see the small companies that promoted themselves regularly in all the film mags.

- Flipping through some old film and animation magazines, I couldn’t help but look at all the old ads for the many animation companies that were ever present and are now gone. In a way, back then, you were pleased to see the small companies that promoted themselves regularly in all the film mags.

You have to remember that animation wasn’t all present back then. It wasn’t easy to find a lot about the medium. Now you just turn on the computer, but back in the ’70s you bought a magazine and cherished the few articles. And when you found something like the Film Comment issue of 1975 (though there were no ads for animation companies in that issue), you kept the magazine close and read and reread the articles. Then you looked at all the ads for the boutique commercial companies.

The following ads all came out of three issues of Millimeter one from 1976 two from 1977.

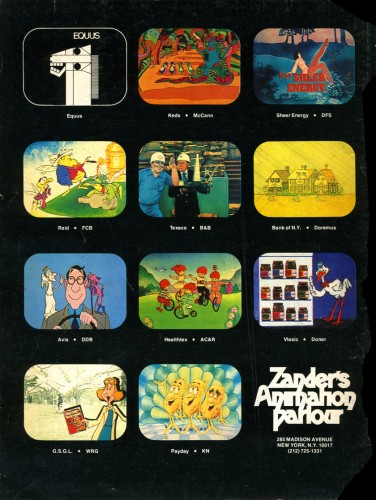

Zander’s Animation Parlour was the largest commercial company

in NY in the 70′s and their ads were the biggest and most entertaining.

They often appeared on the back cover of these magazine issues.

Ads changed from issue to issue, so someone in the studio

kept designing them. Jack Produced the spots with animators

Doug Crane, Dean Yeagle and Bill Railey on staff.

Phil Kimmelman’s studio, PK&A, was also a dominating advertiser.

Though their ads changed, as well, this one appeared often enough

to be recognizable.

Phil Kimmelman ran the studio with Bill Peckman supervising and

doing layout. Jack Schnerk, Sal Faillace and Dante Barbetta were

regularly used animators.

Perpetual Motion was another large studio run by Buzz Potamkin.

Their ads weren’t as obviously frequent as the other two, but

they did focus on their art.

Buzz ran the studio in NY with animators Vinnie Cafarelli and Jan Svochak

on staff. Candy Kugel was the up and coming star to emerge.

Bill Melendez, on the west coast, did the Charlie Brown shows, but

his studio also did commercials (often featuring Charlie Brown.)

Kurtz and Friends, in California, was hot.

Herb Stott’s Spungbuggy Works certainly caught my eye.

That name for a studio was genius.

Murakami Wolf, Swensen was a diverse animation studio that seemed to do everything from “The Point” to “Biker Mice From Mars” to commercials.

Mort and Millie Goldscholl ran the largest studio in Chicago, Goldscholl Ass.

Their focus seemed to be graphic animation.

IF Studio was run by cameraman, Carlos Sanchez. They filmed animation

and produced a lot of graphic animation.

Bajus Jones was a hip studio operating out of Minneapolis. They caught a lot of attention and did excellent character animation.

Ray Seti was an animator who opened his own one-man studio. He did a

lot of animatics for commercials and thrived for quite some time.

I have a funny story about meeting him that I’ll hold for another time.

George McGuinnes and Mark Howard ran The Image Factory. They did

dynamic graphic animation. I think I did the only drawn animation for

them – which they used for a graphic spot.

Action Analysis &Animation Artifacts &Articles on Animation &Disney 10 Dec 2008 09:11 am

Tytla’s Action Analysis

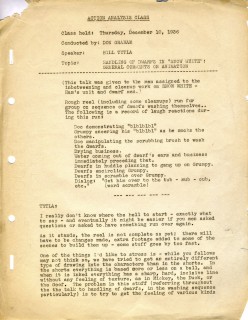

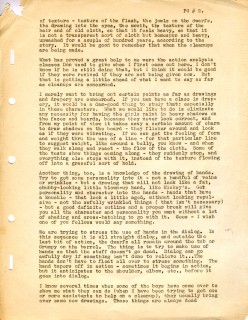

– After posting the fine drawings by Bill Tytla, and following with the “Washing sequence” board drawings it’s on appropriate to offer one of the Action Analysis classes Tytla gave at the Disney studio, after hours. This one took place on December 10th, 1936 – 72 years ago today.

– After posting the fine drawings by Bill Tytla, and following with the “Washing sequence” board drawings it’s on appropriate to offer one of the Action Analysis classes Tytla gave at the Disney studio, after hours. This one took place on December 10th, 1936 – 72 years ago today.

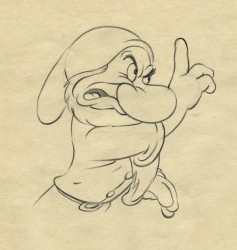

Tytla and Fred Moore were the leadaing animators of the seven dwarfs – supervising and handling seven wholly different personalities each with relatively little screen time to relay their individual traits.

This article is chiefly concerned with the sequence of the dwarfs gathered around the wash tub cleaning themselves for dinner.

__Click image to enlarge to see full dwg._._Grumpy, of course, sits out the experience.

____________________________________They sing the washing song, “blblblbl.”

1

1  2

2(Click any image to read.)