Category ArchiveBooks

Bill Peckmann &Books 04 Apr 2013 06:51 am

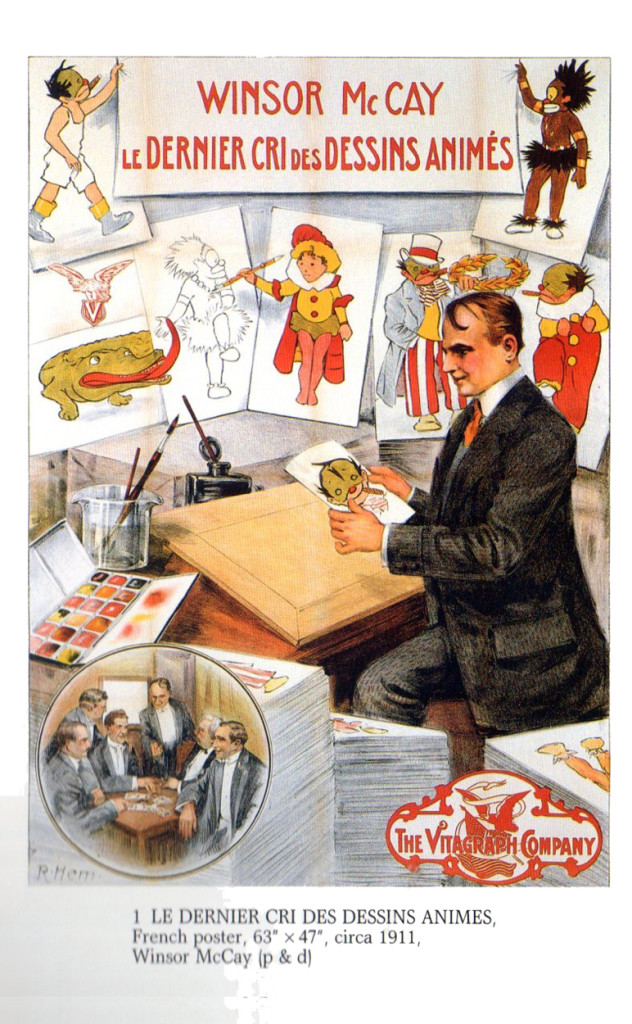

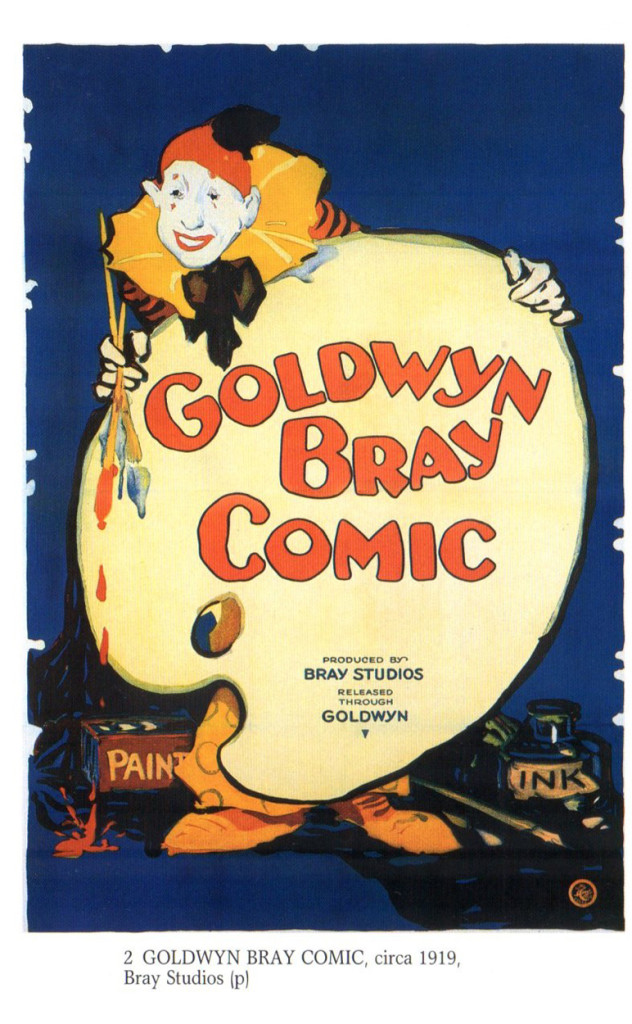

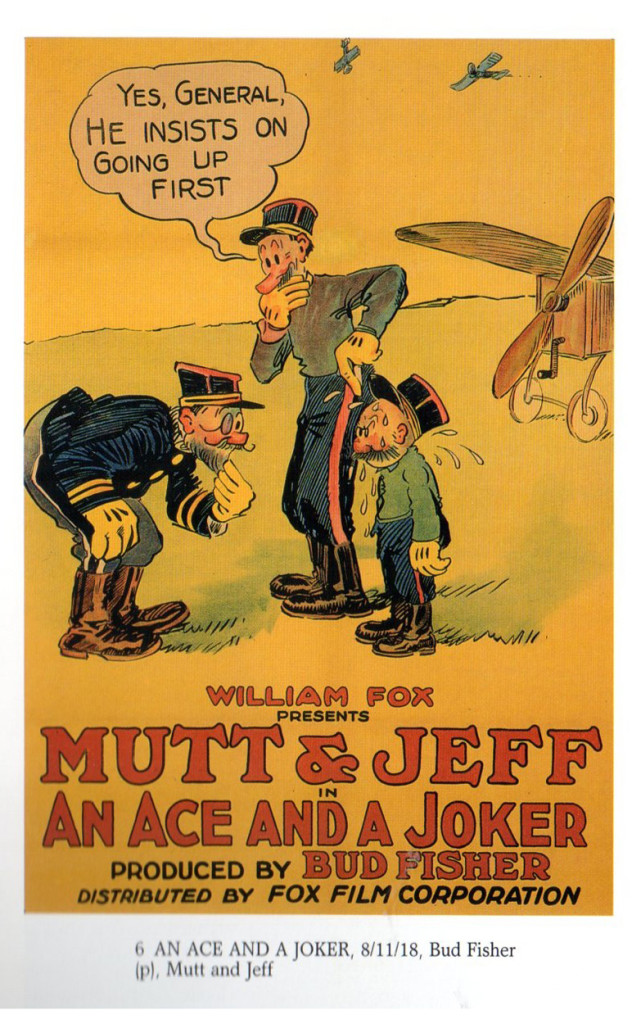

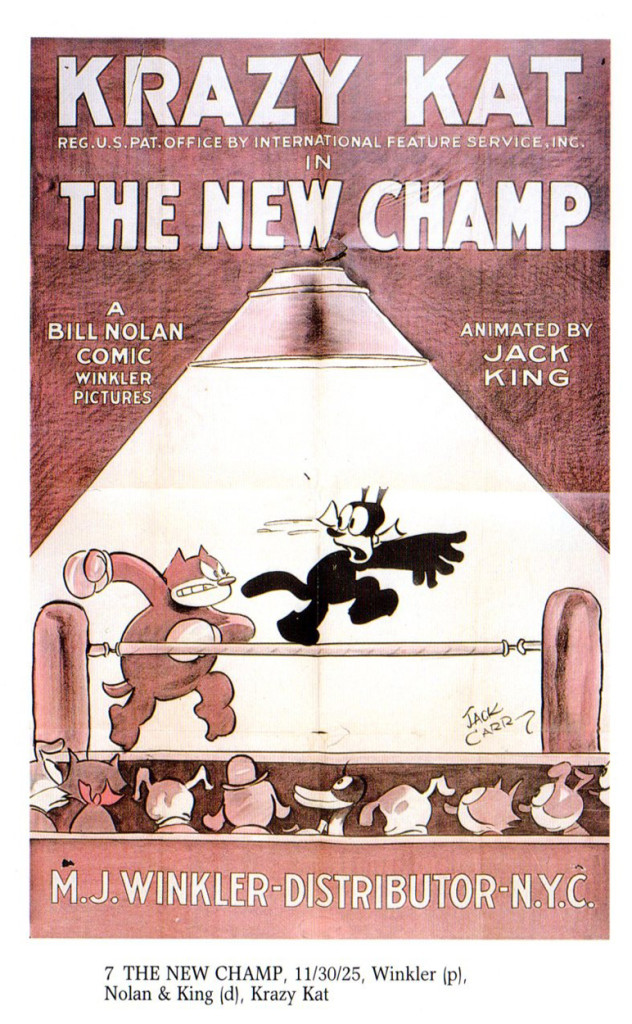

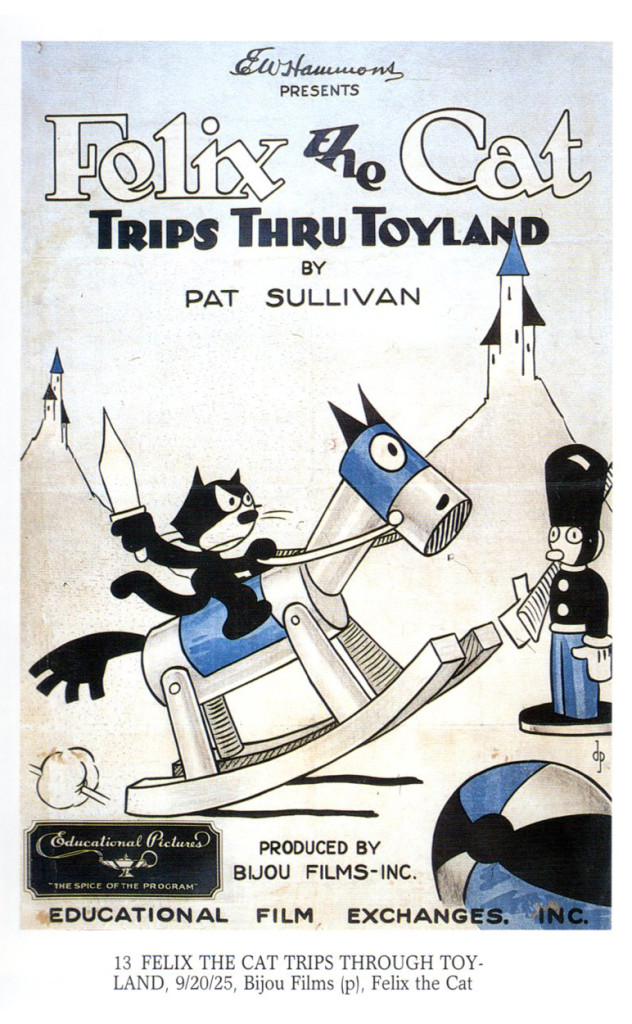

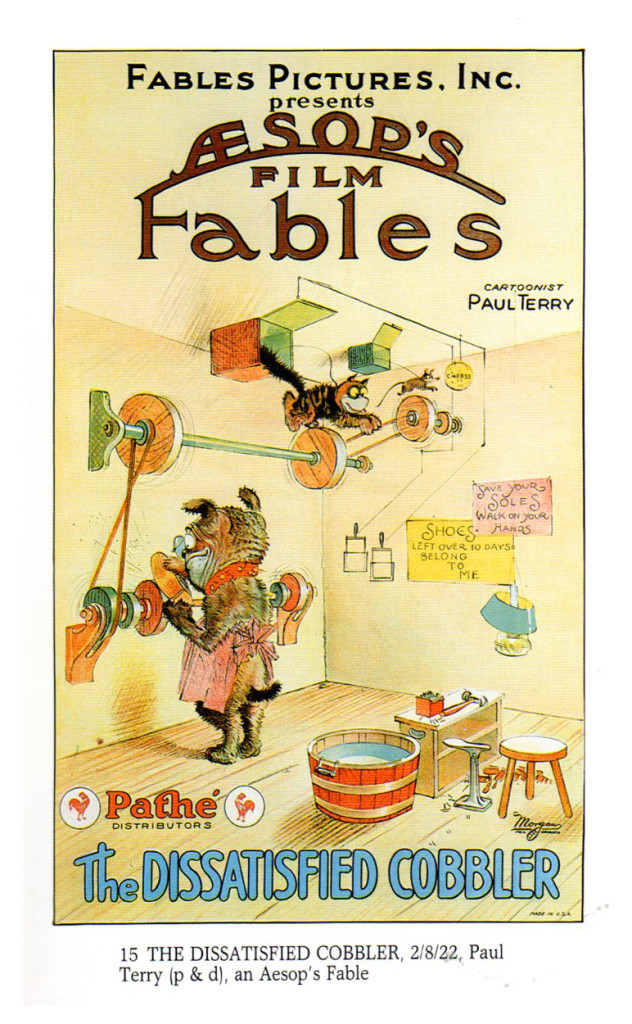

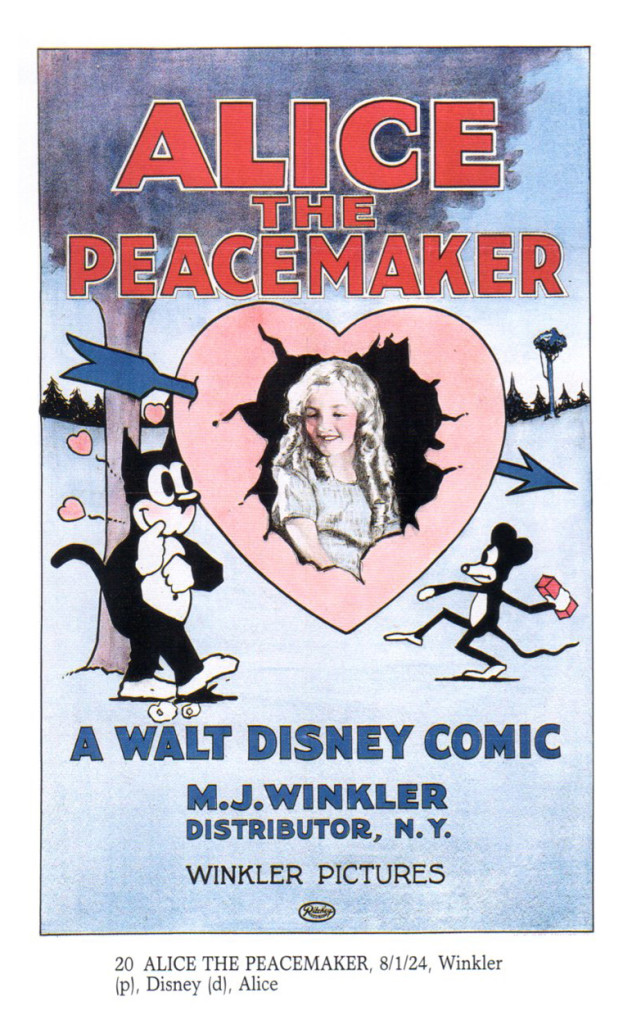

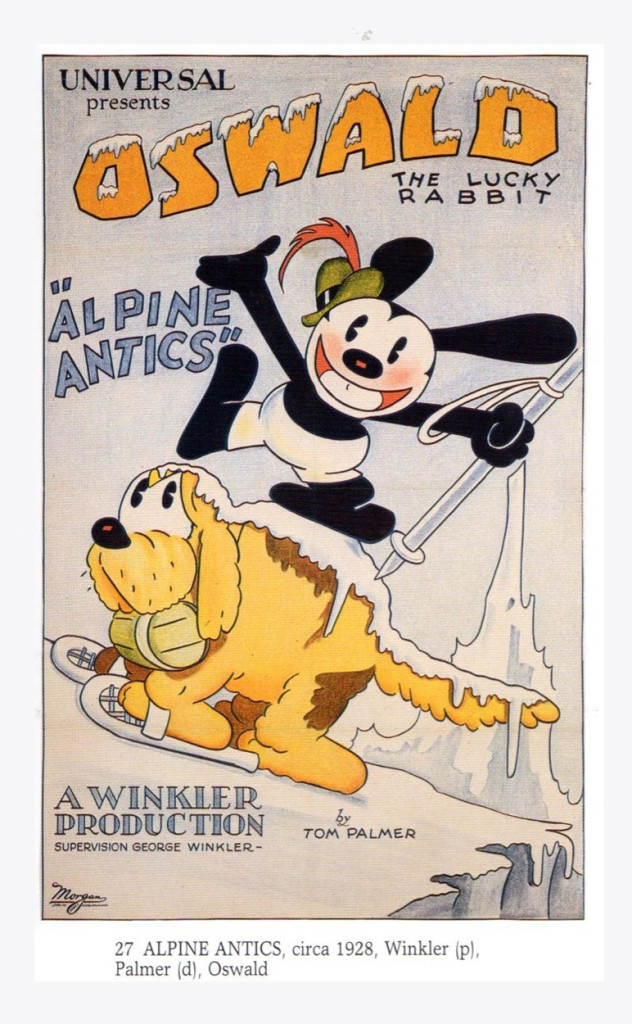

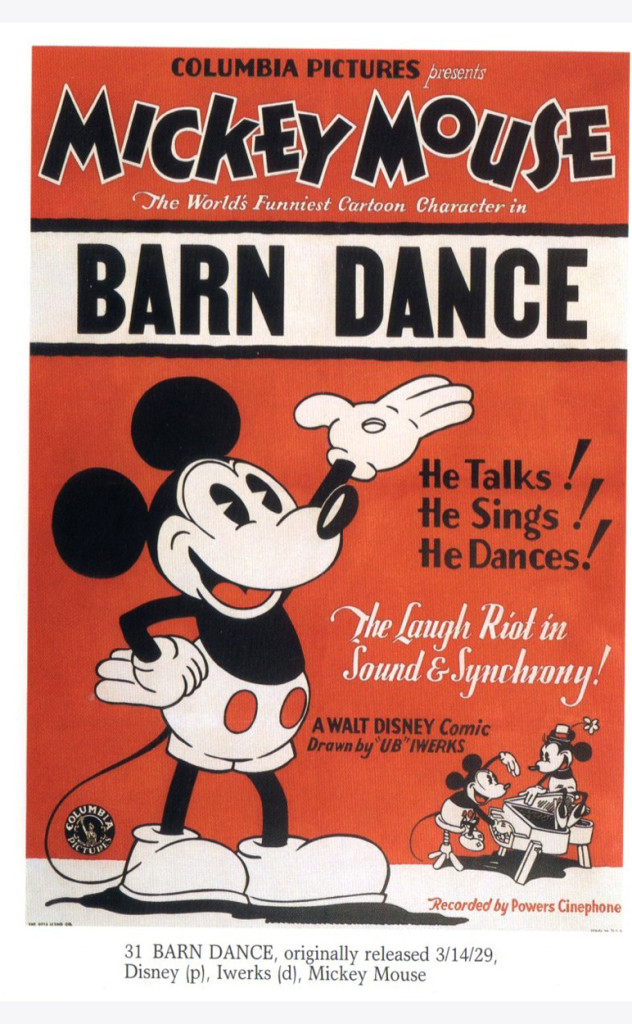

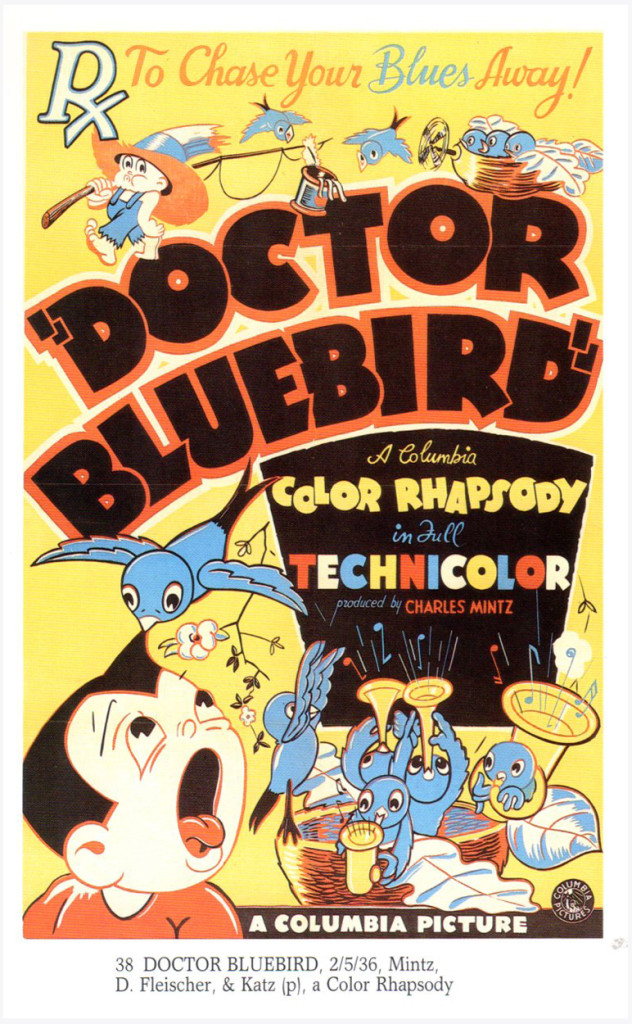

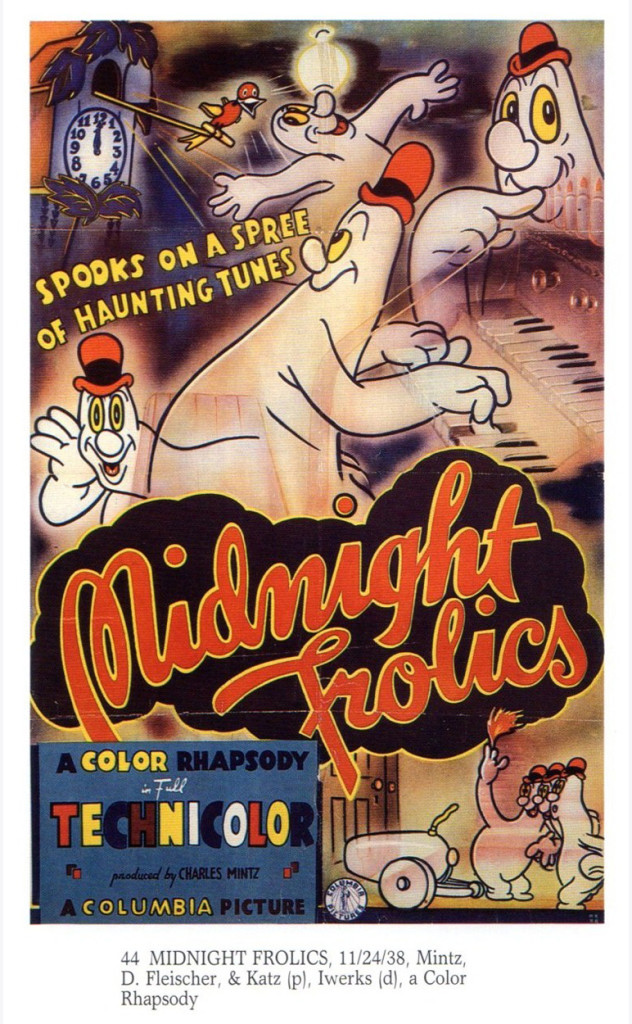

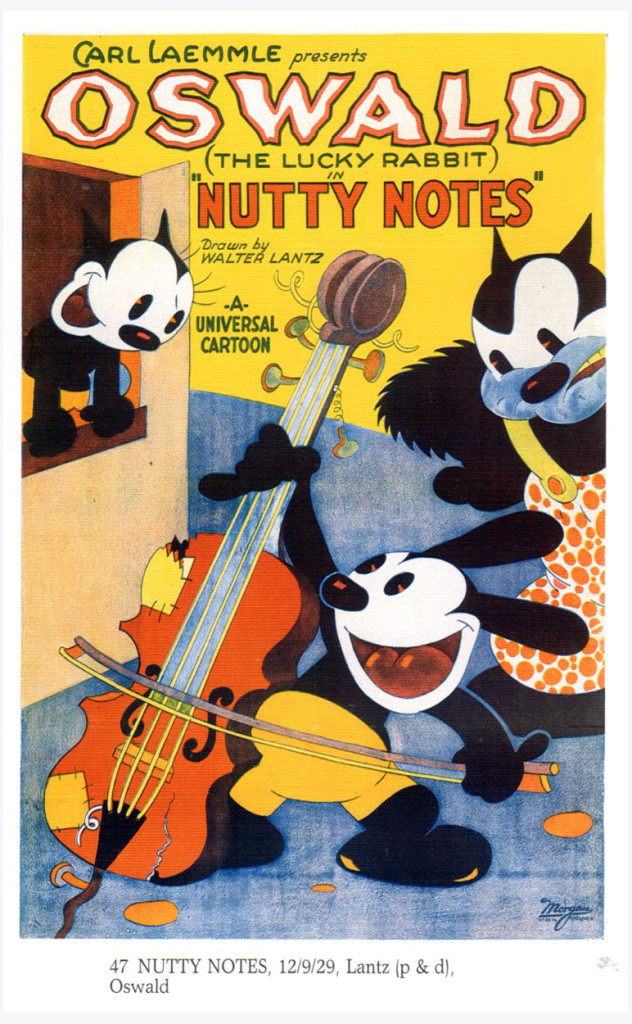

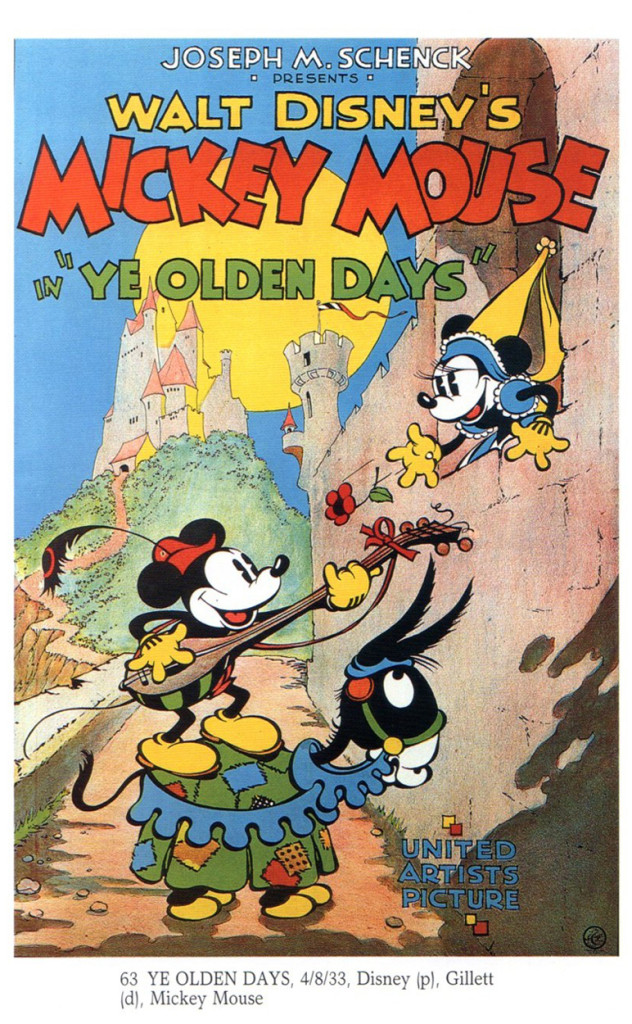

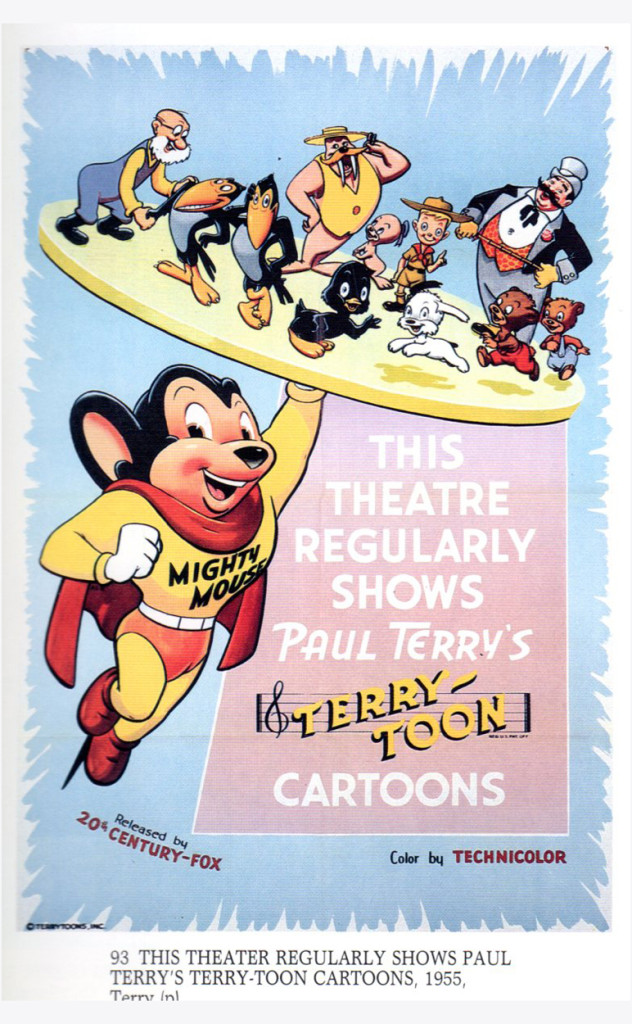

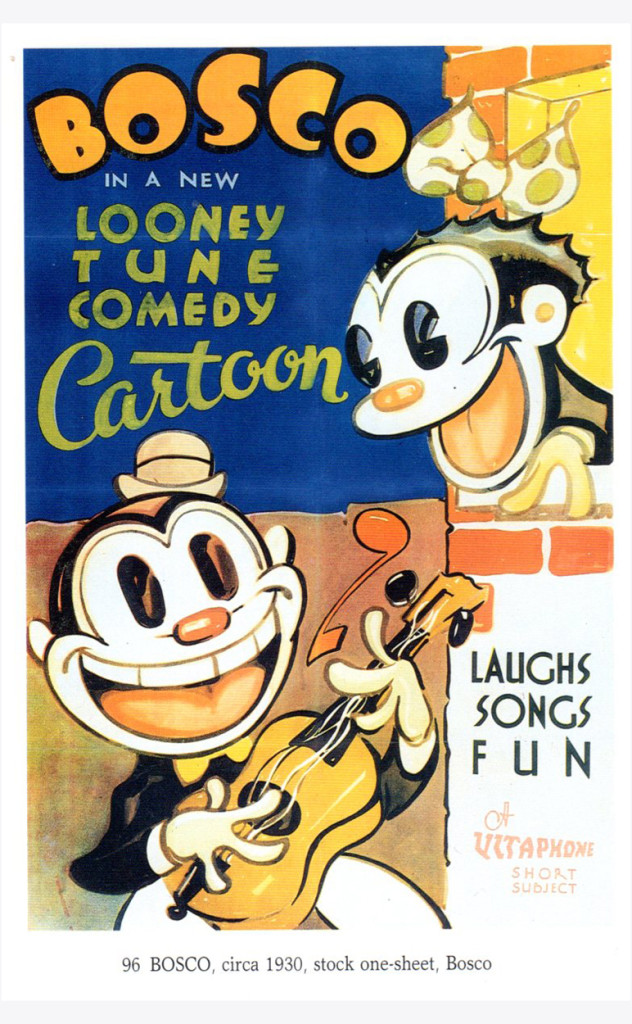

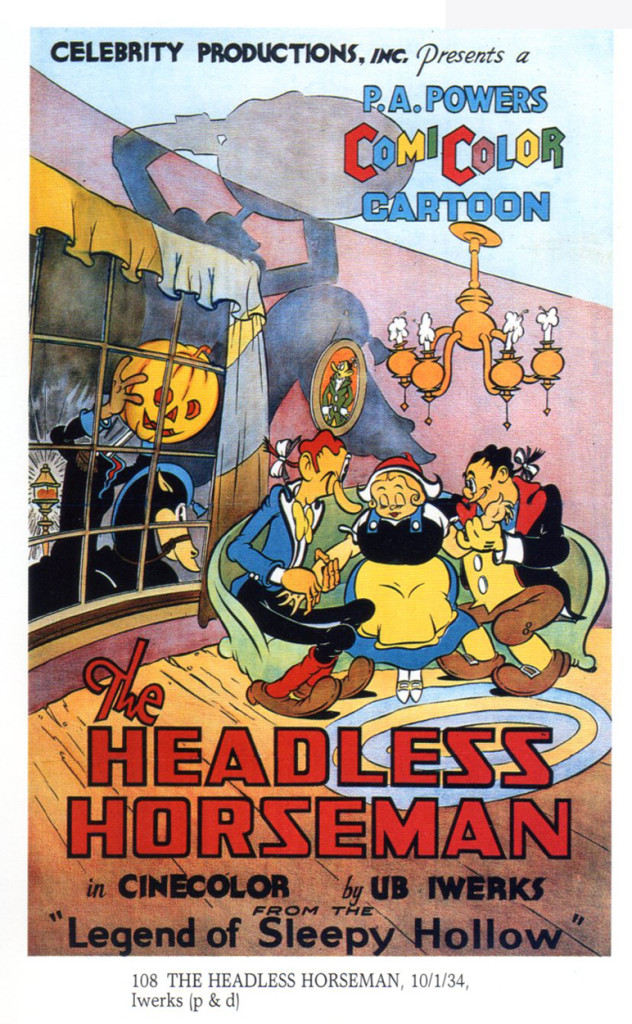

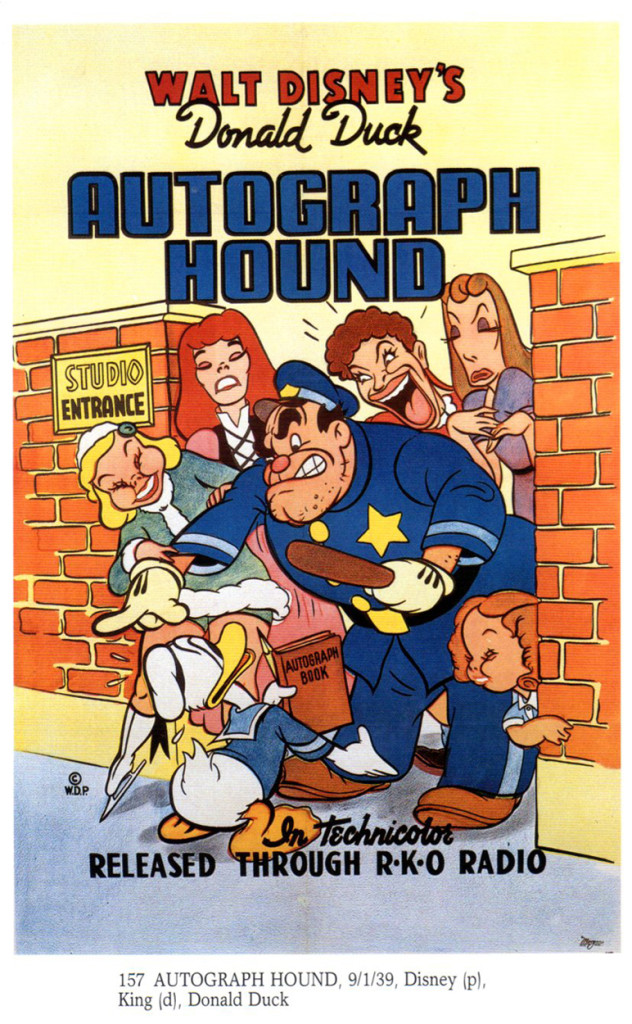

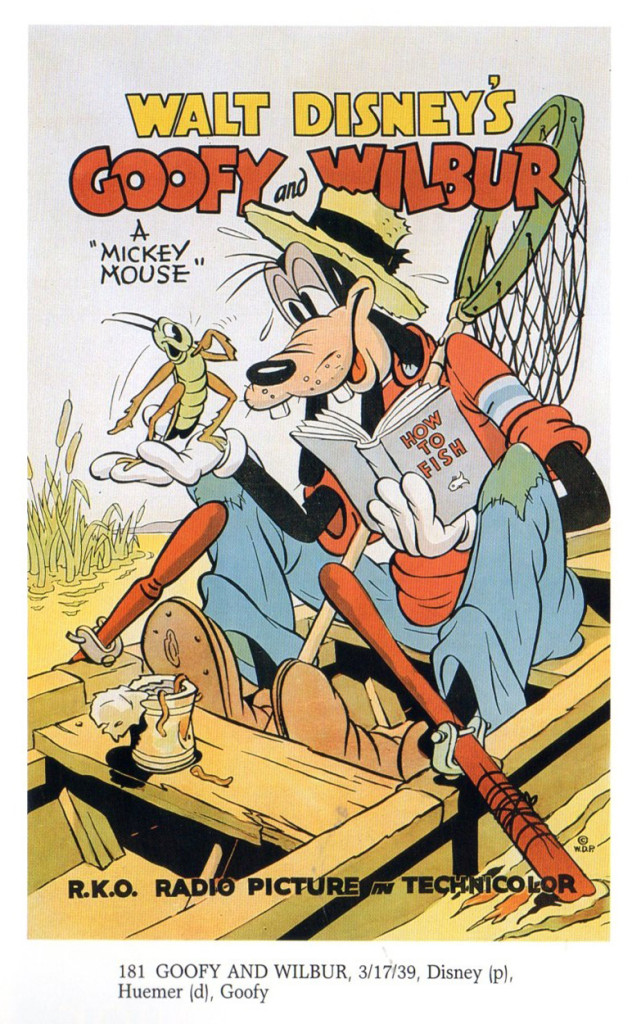

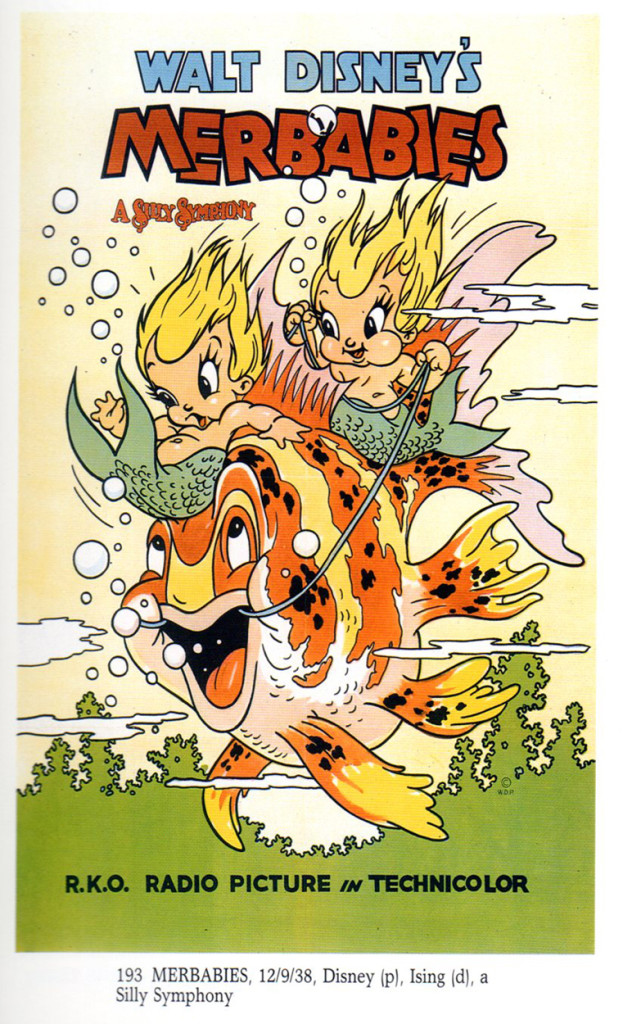

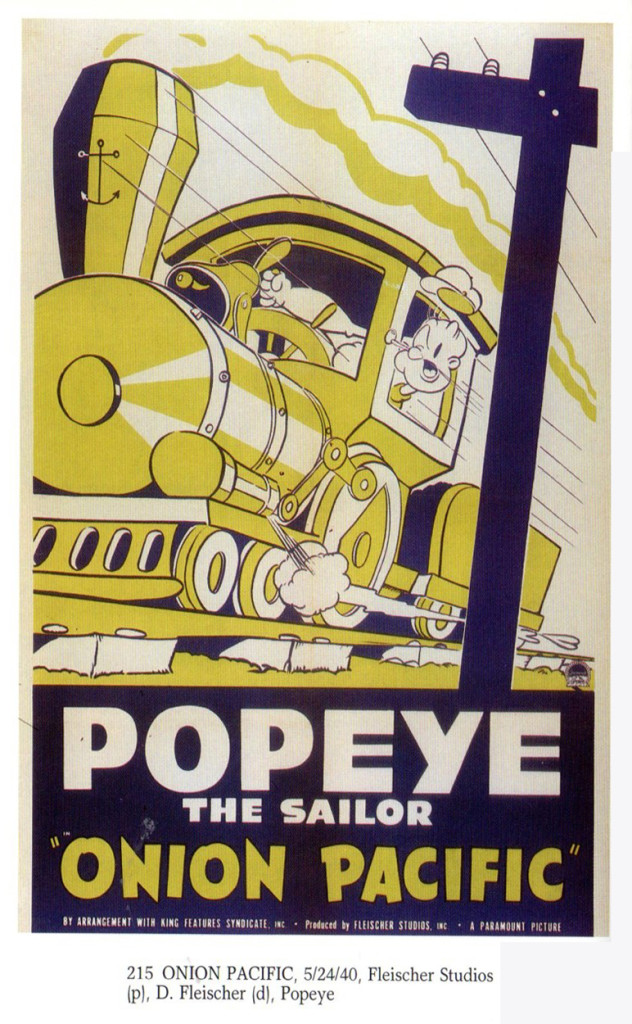

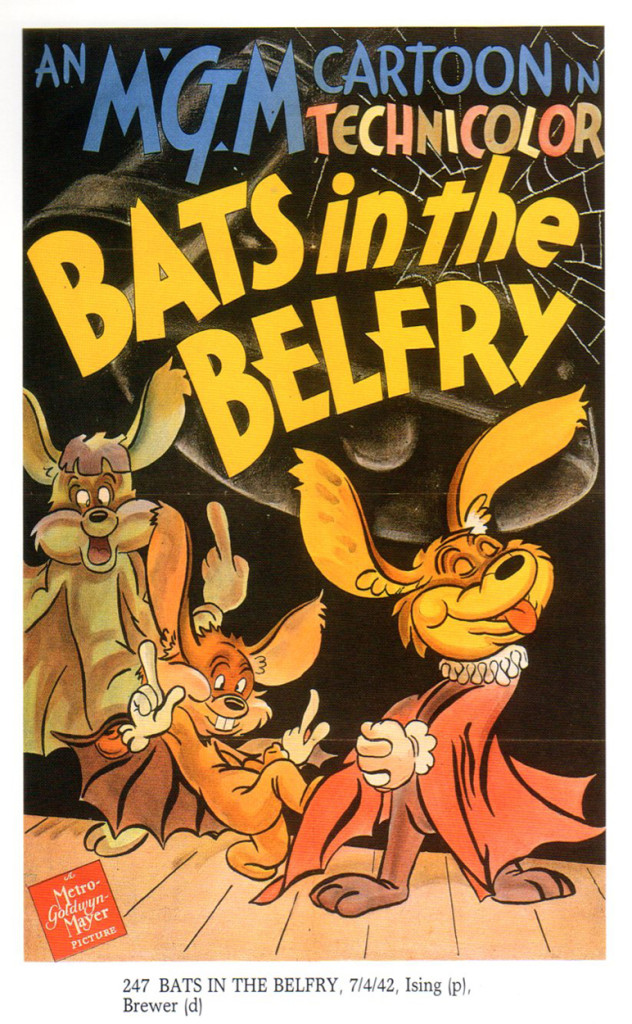

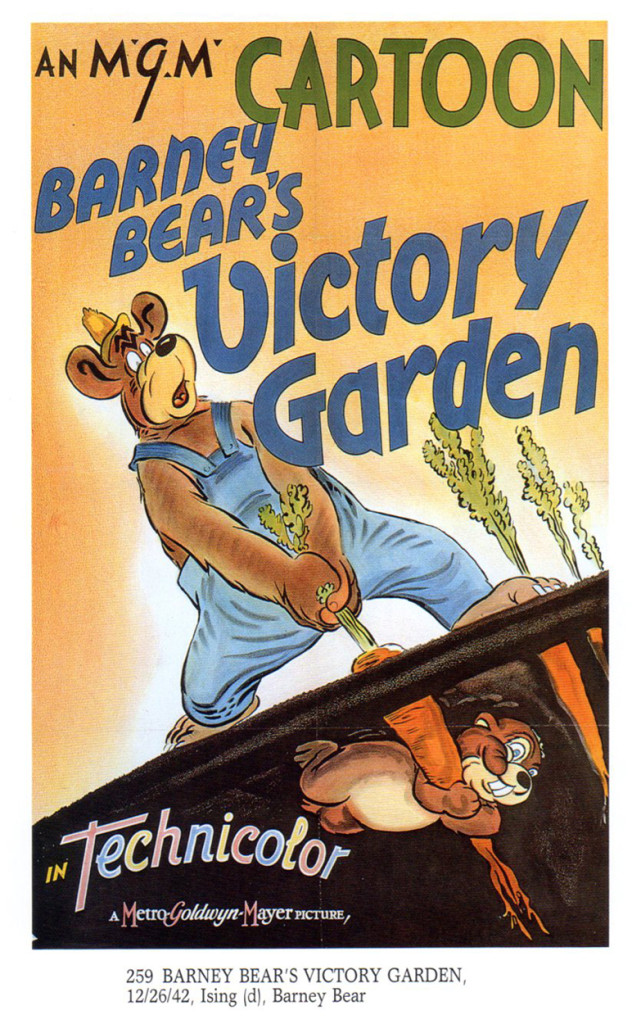

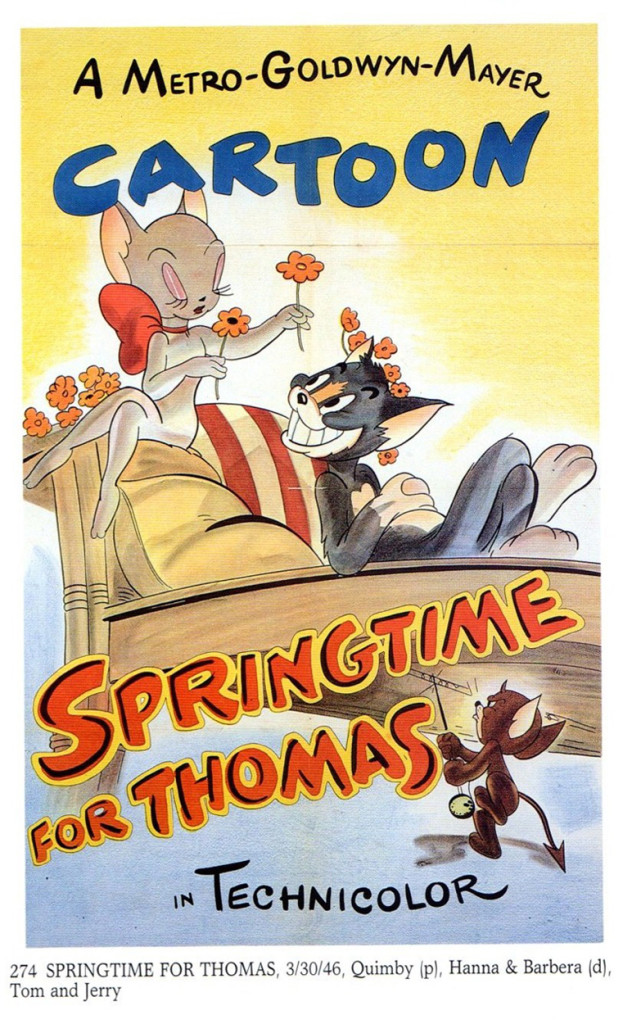

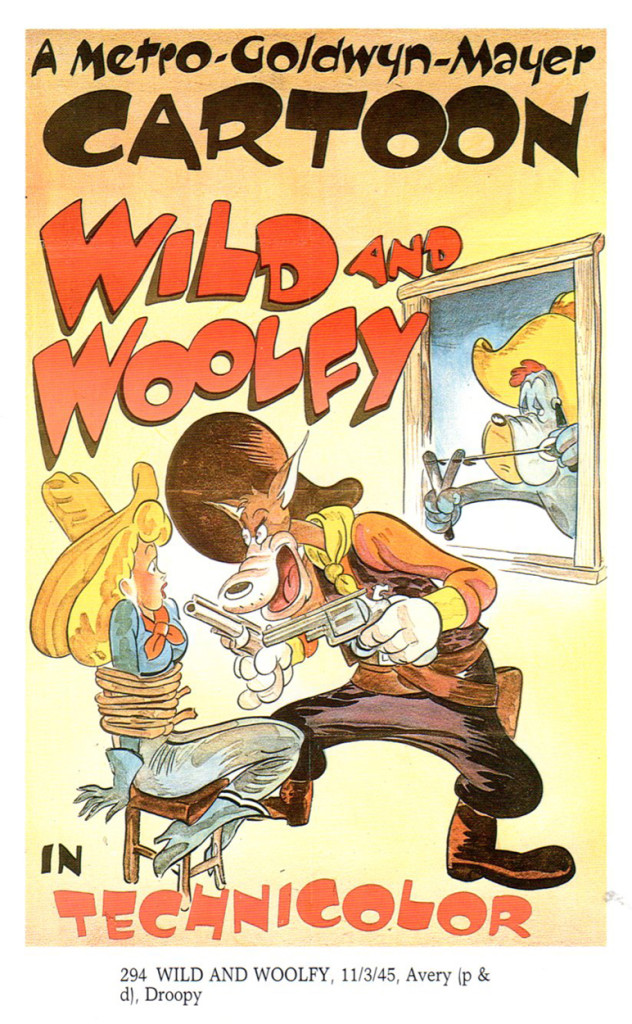

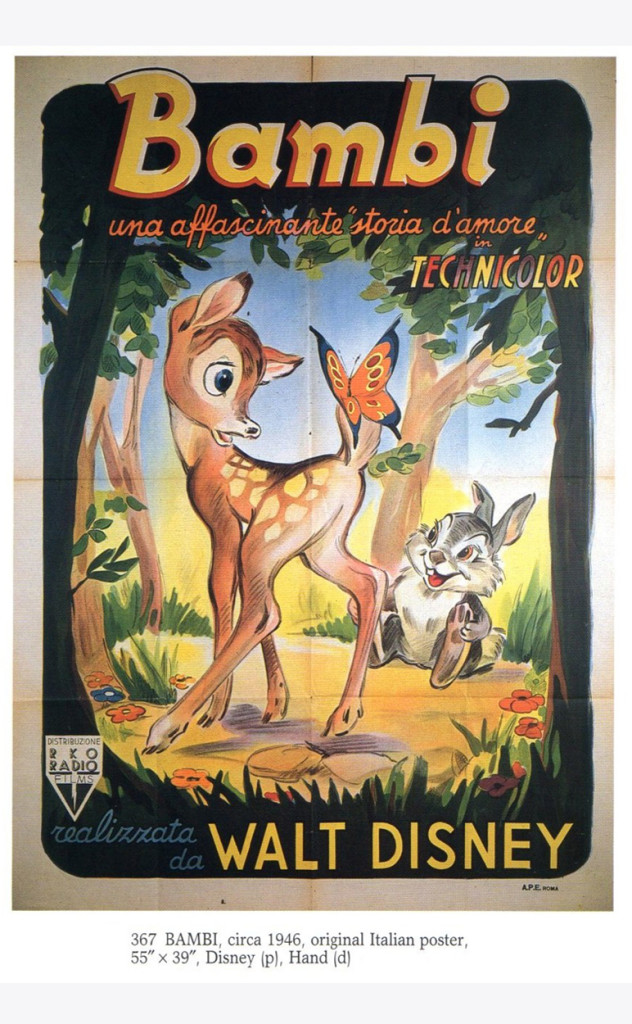

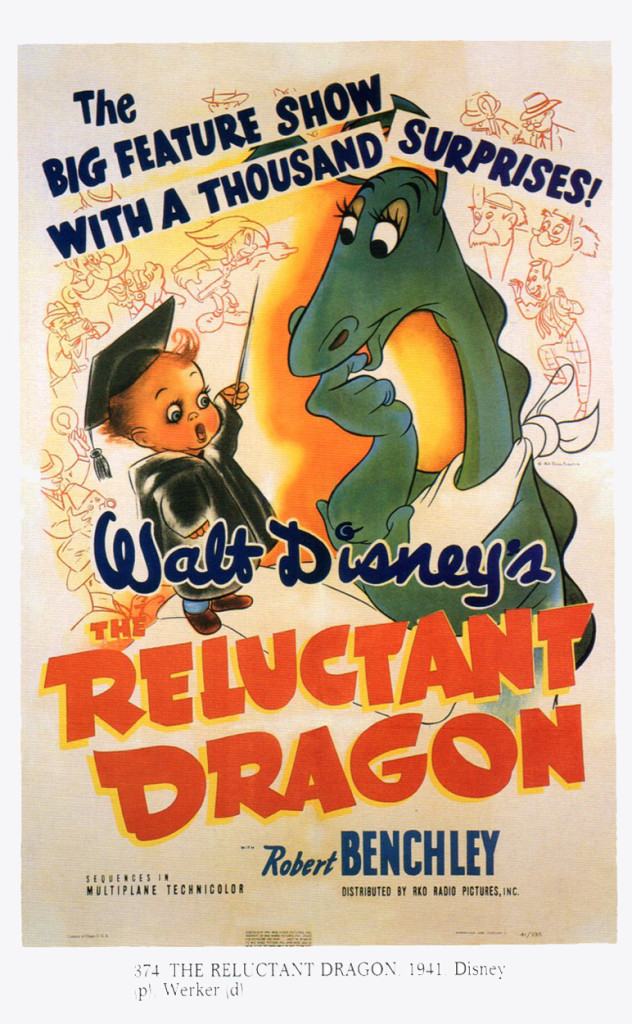

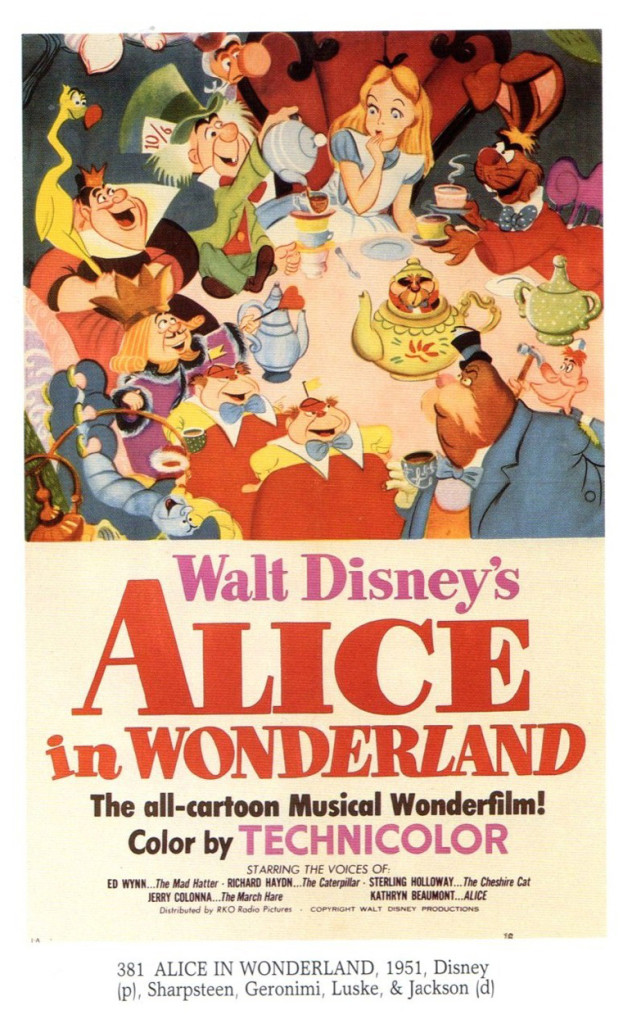

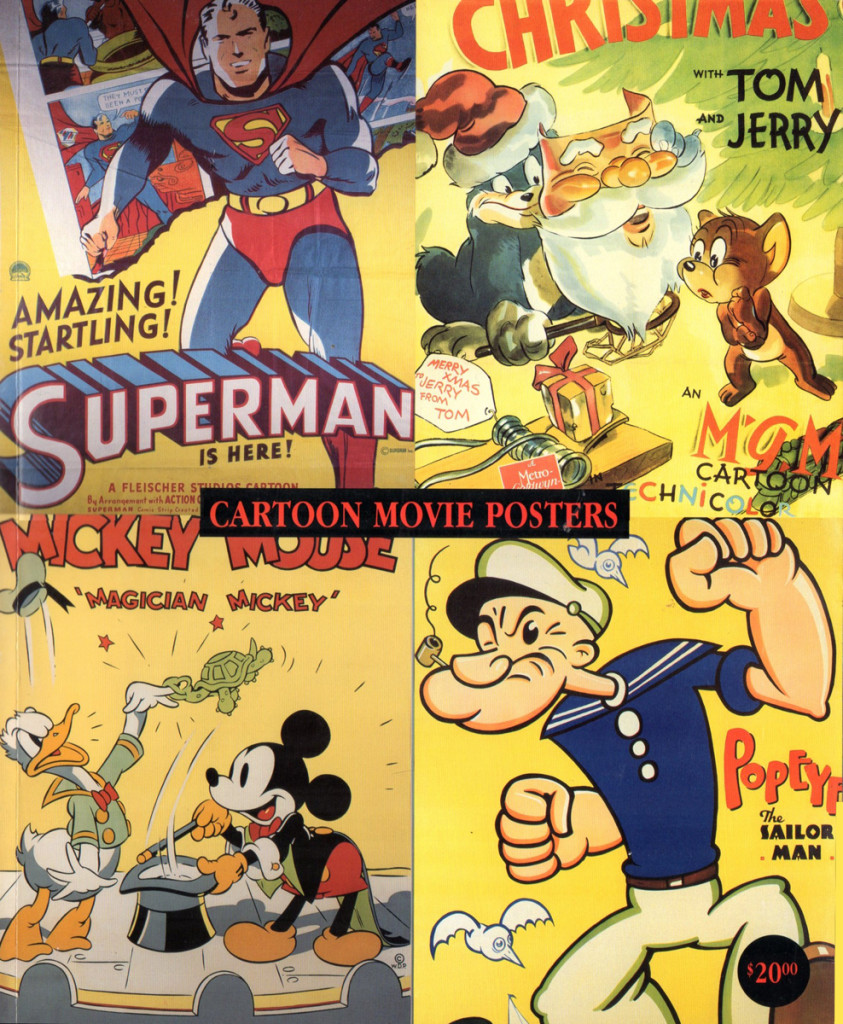

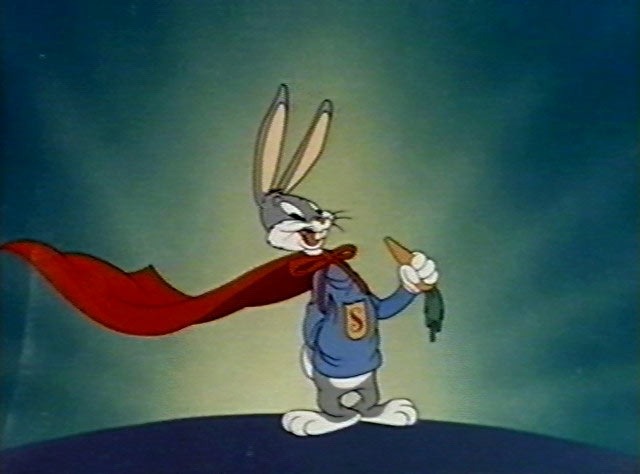

Cartoon Posters

Bill Peckmann sent me scans from a book of his on “Cartoon Movie Posters.” Bill sends pages from some of the early cartoons and begins to get into the Disney animated features. If there’s interest from you, he’ll send more from the book. Here’s Bill’s comments:

- This is the “Cartoon Movie Posters” book published by Bruce Hershenson in the 1990′s, volume 1. He mentions plans for more volumes; I don’t know if they ever came about. This paperback has almost 400 posters in it and offers plenty more to post.

The Book’s Cover

Bill Peckmann &Books &Illustration 29 Mar 2013 03:08 am

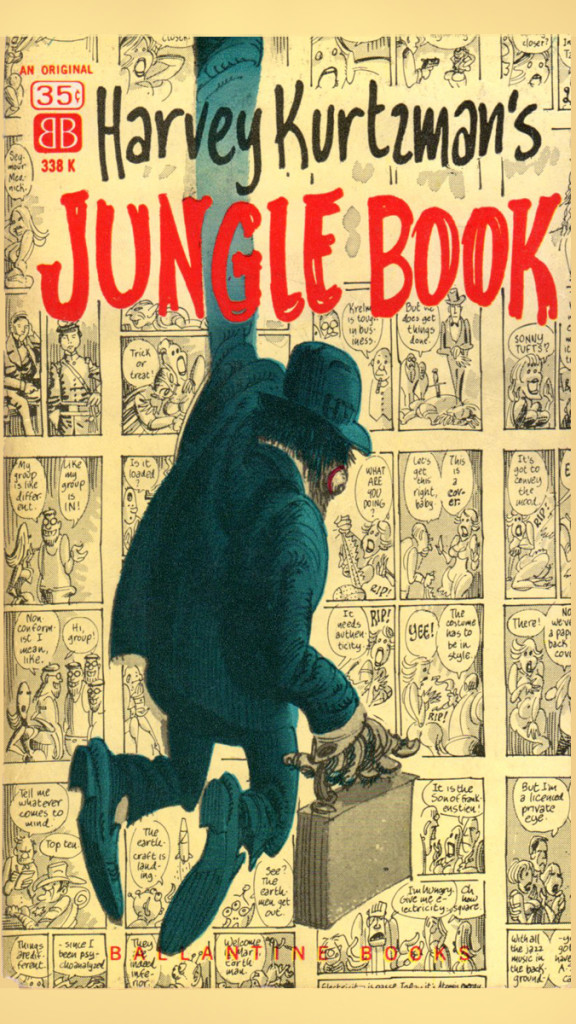

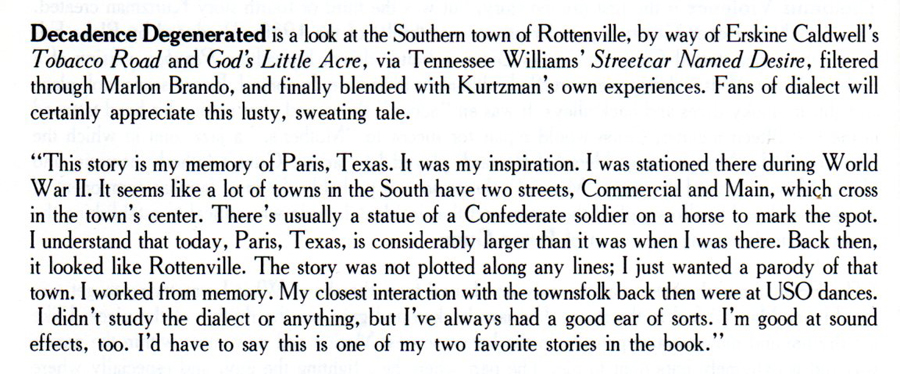

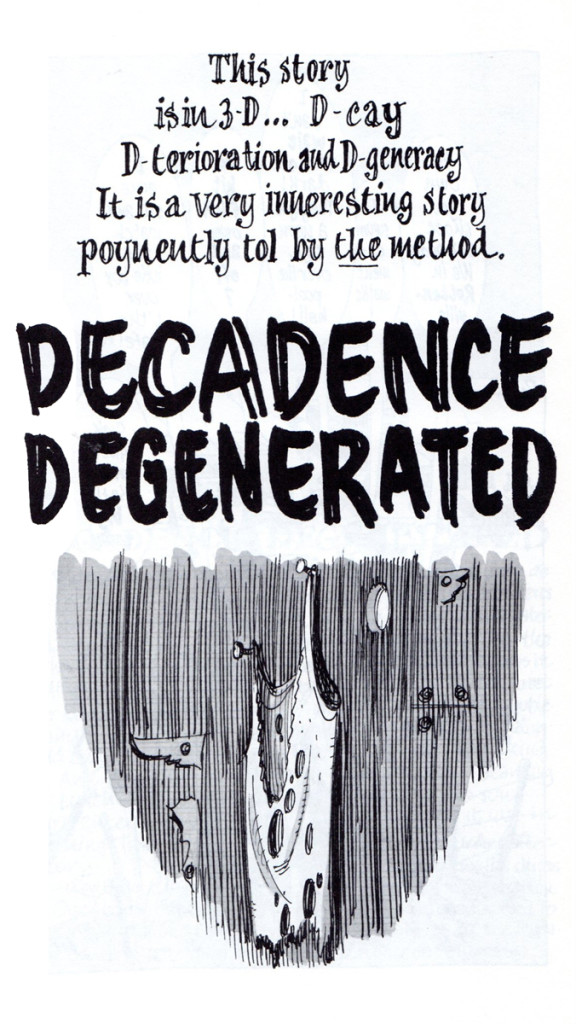

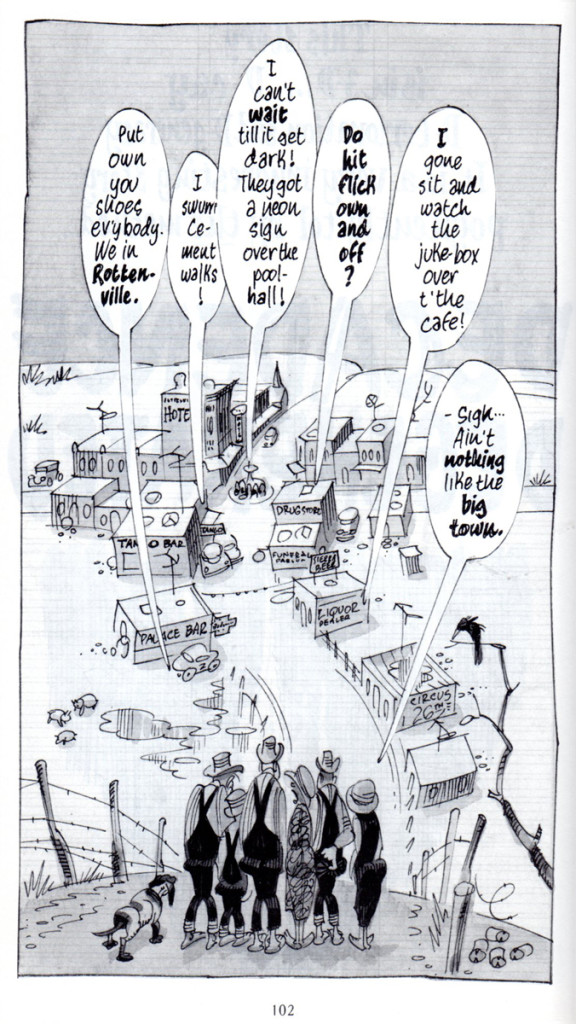

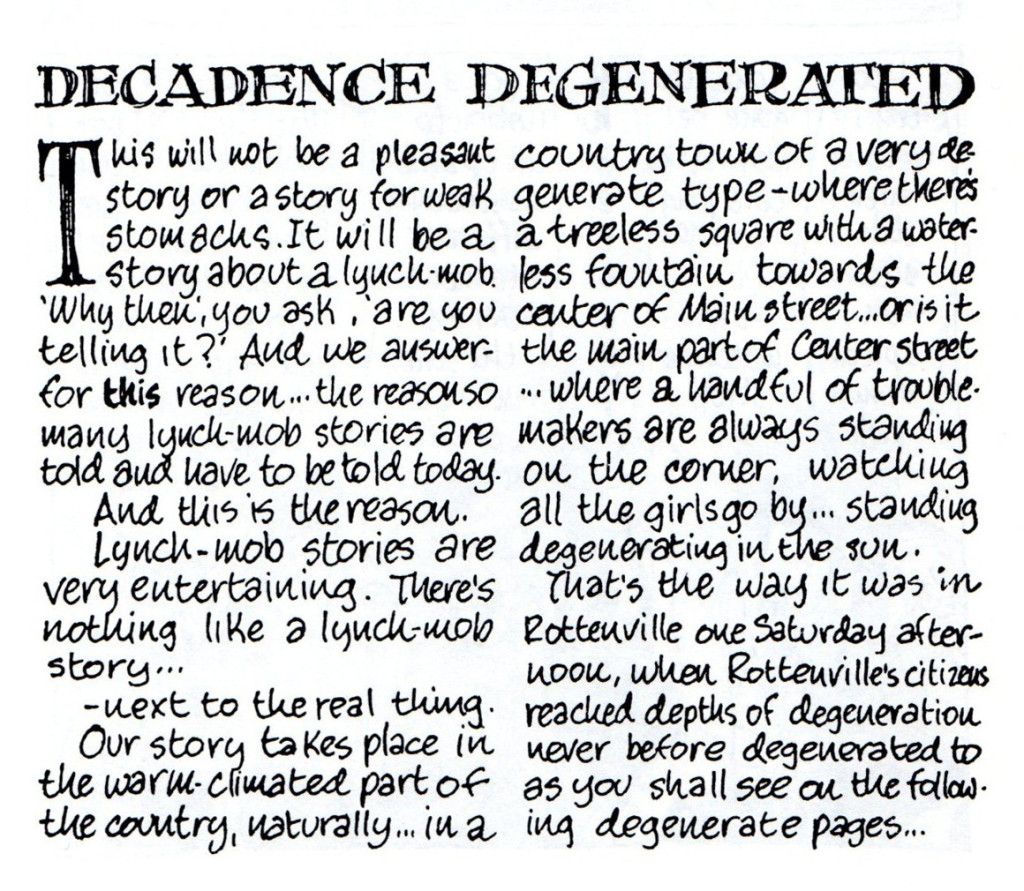

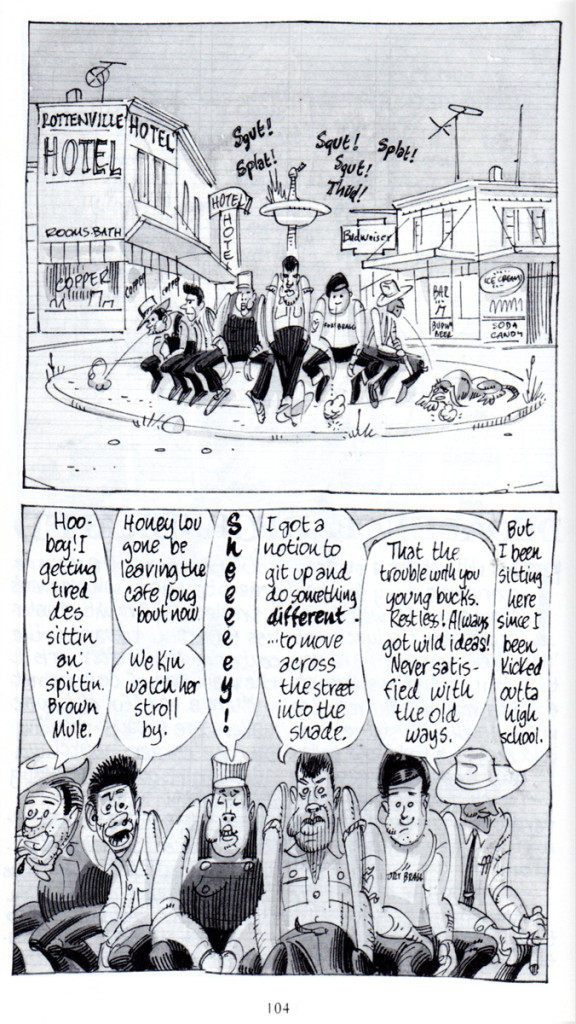

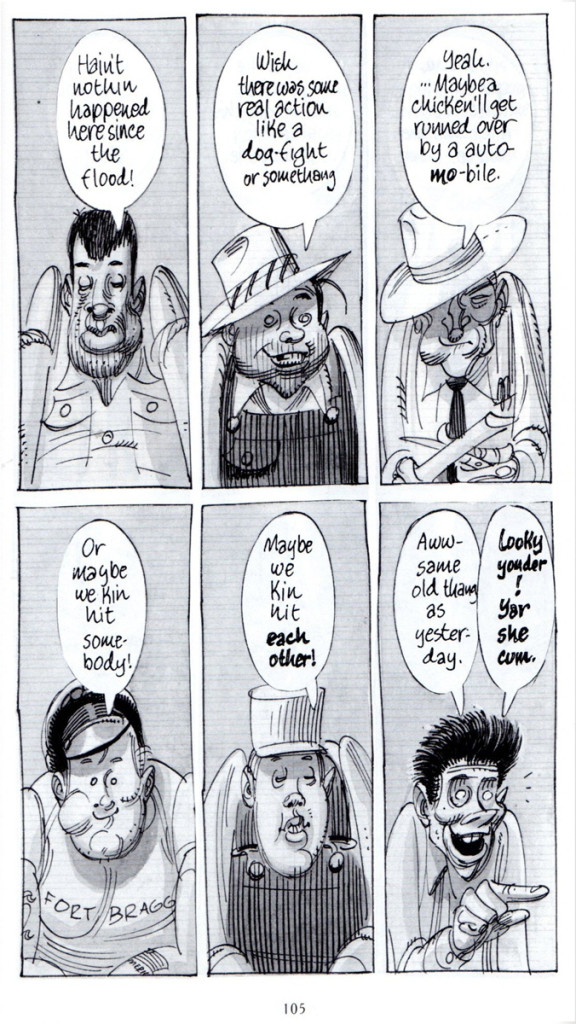

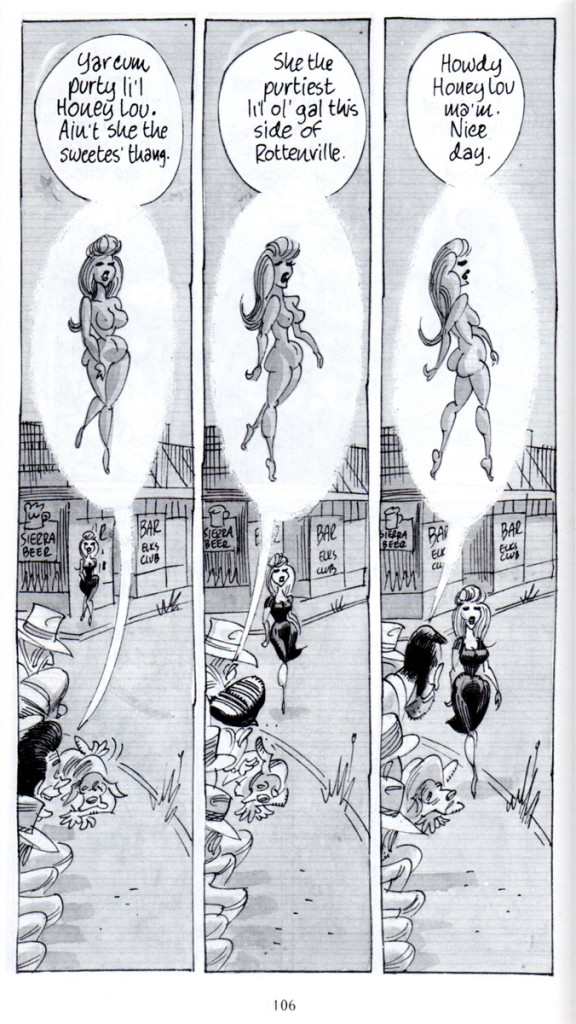

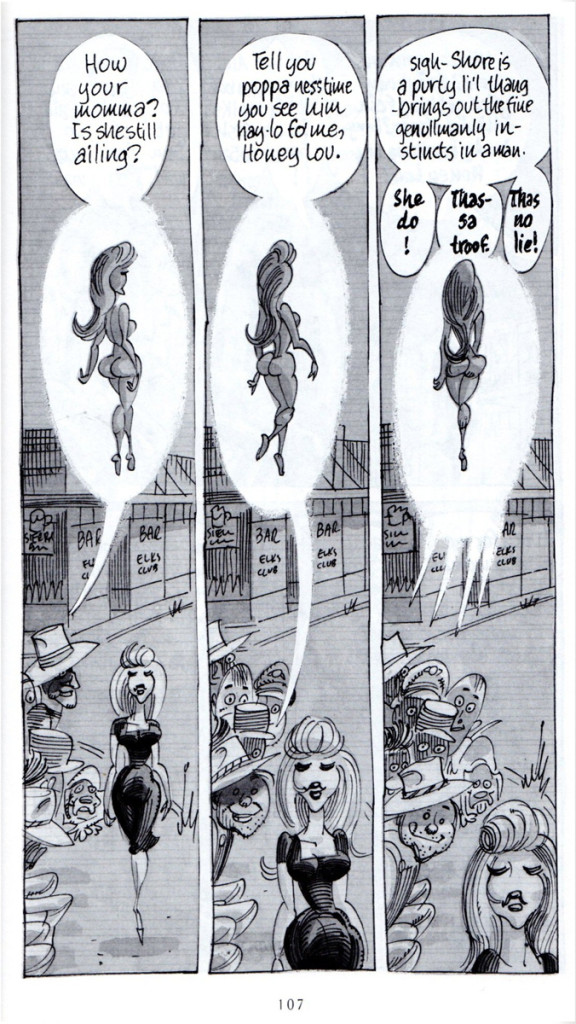

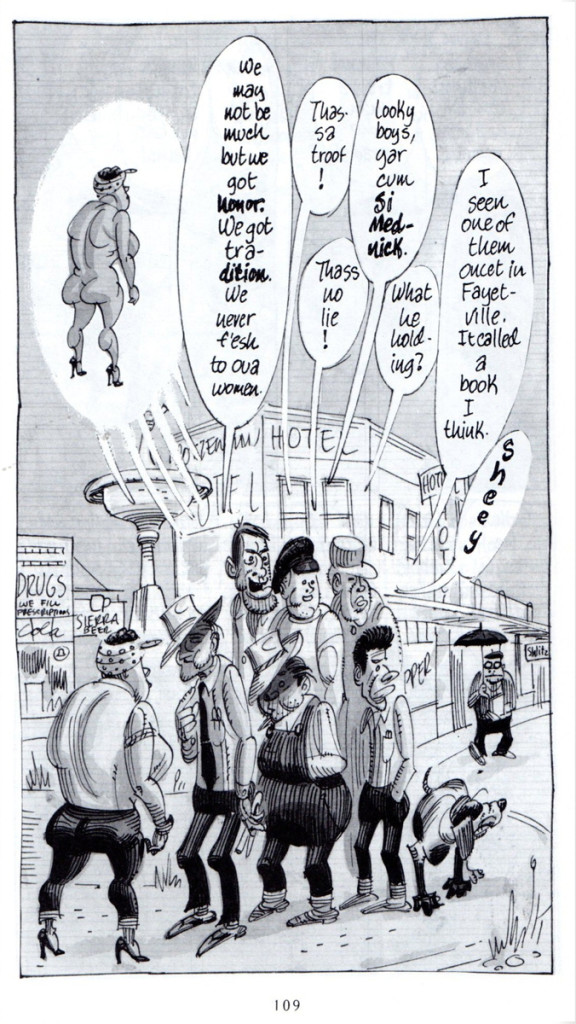

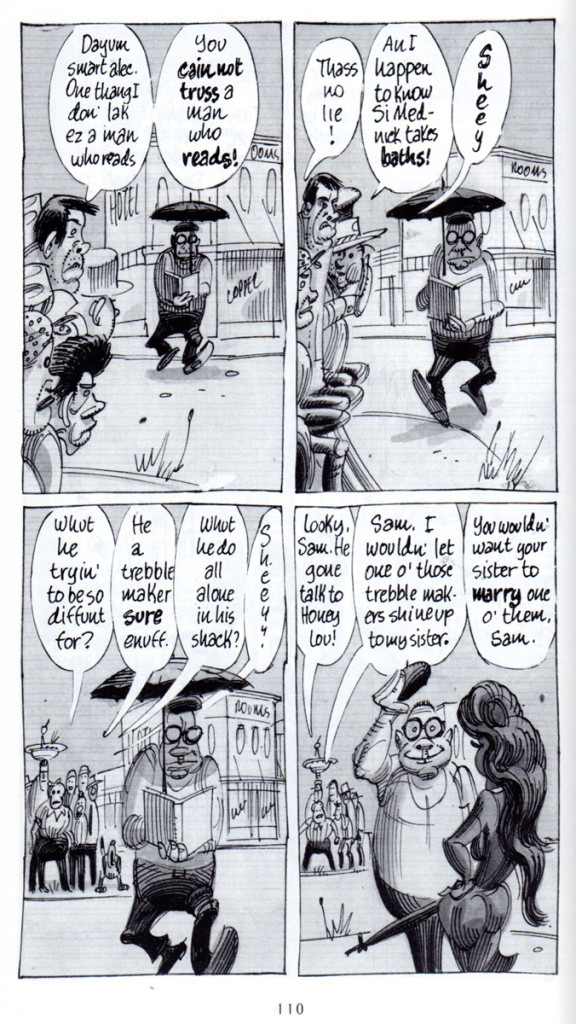

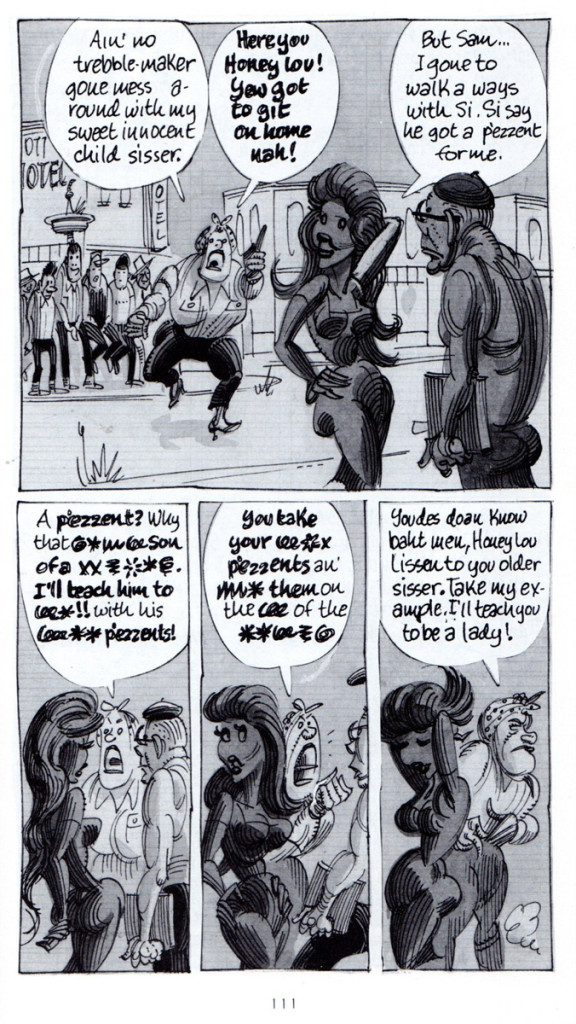

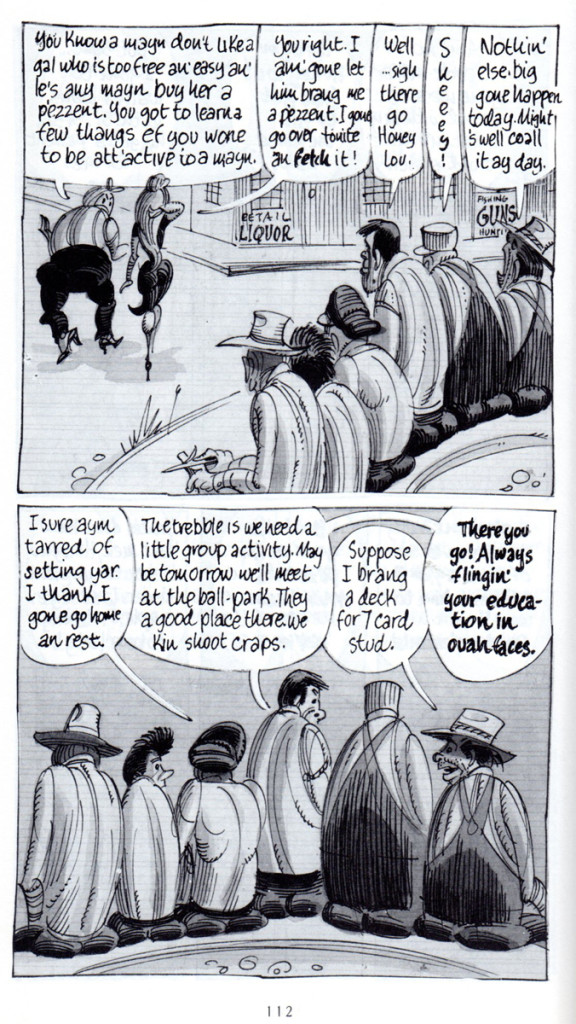

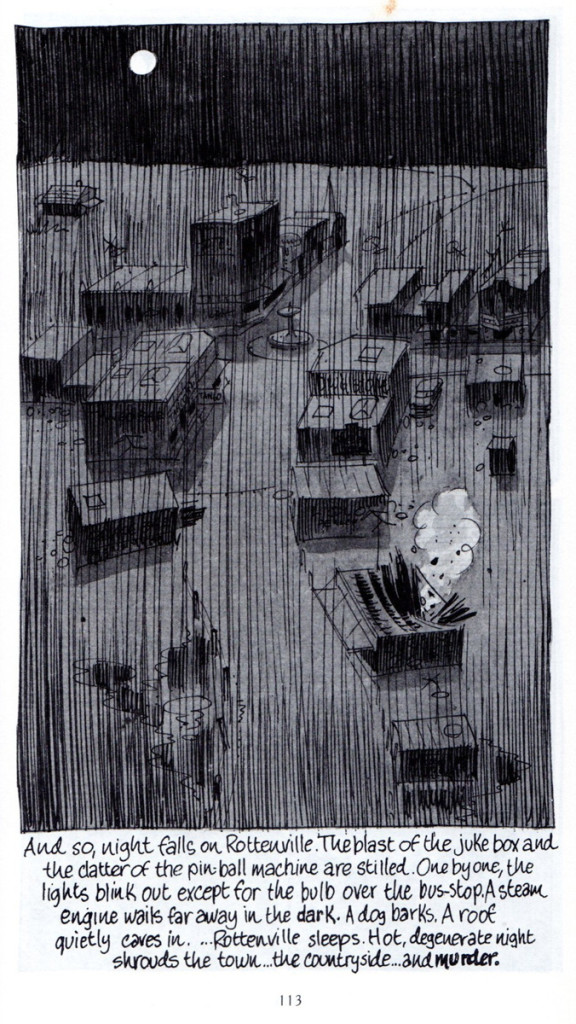

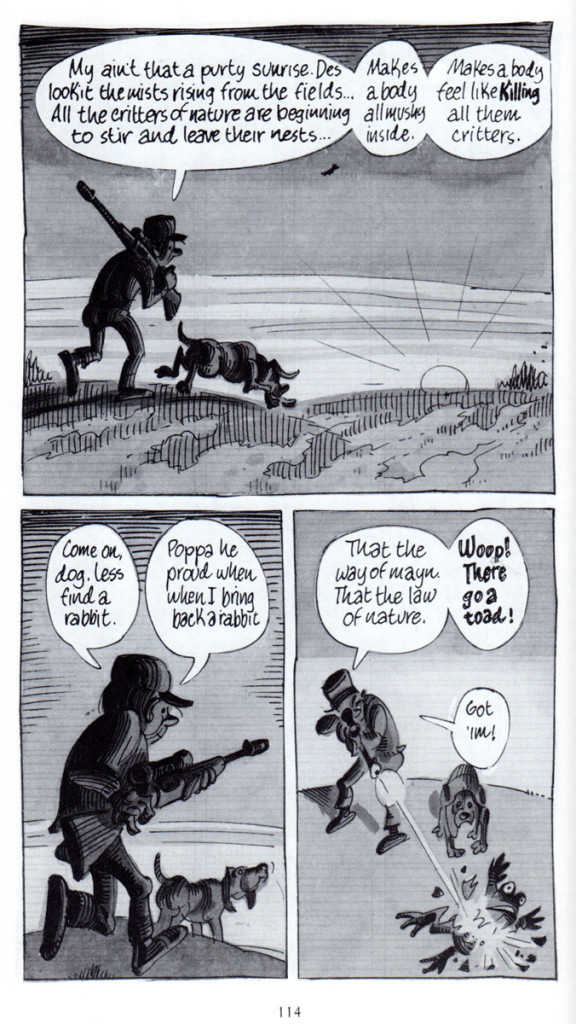

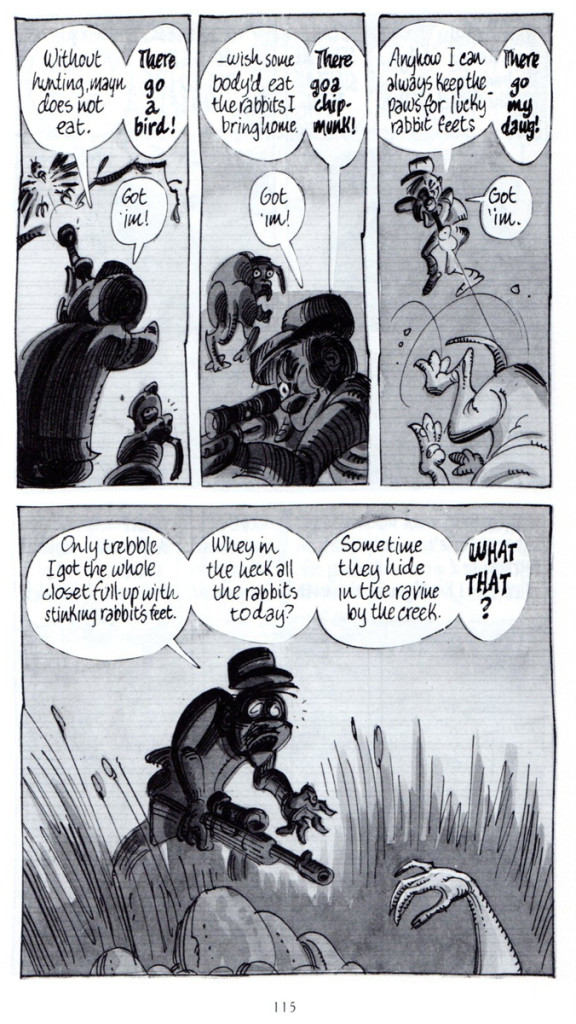

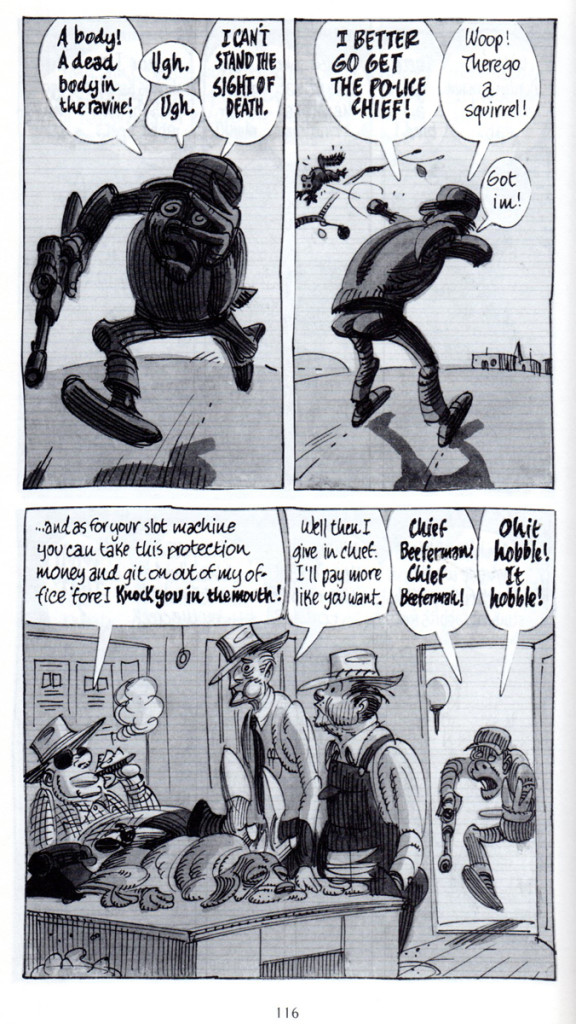

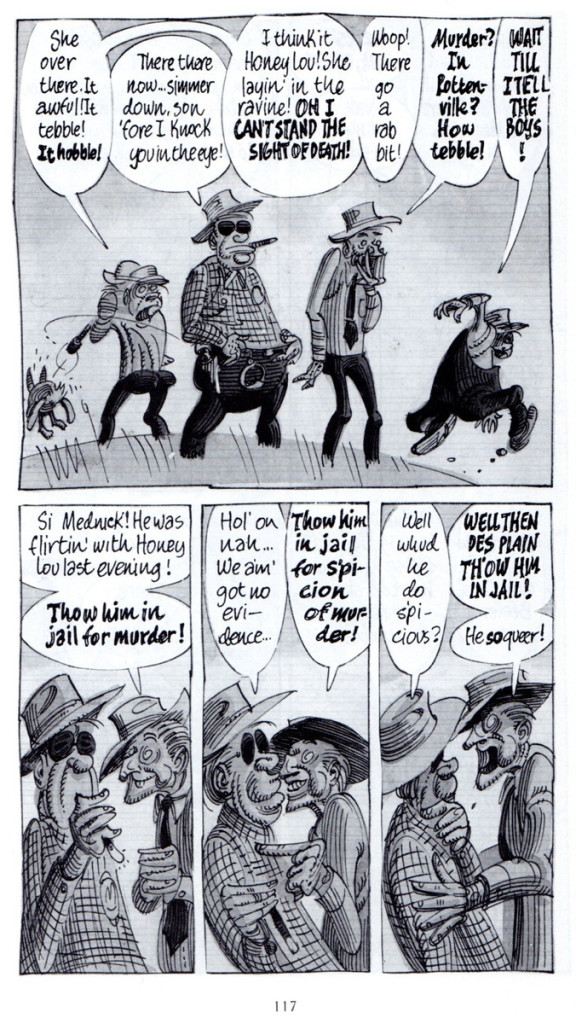

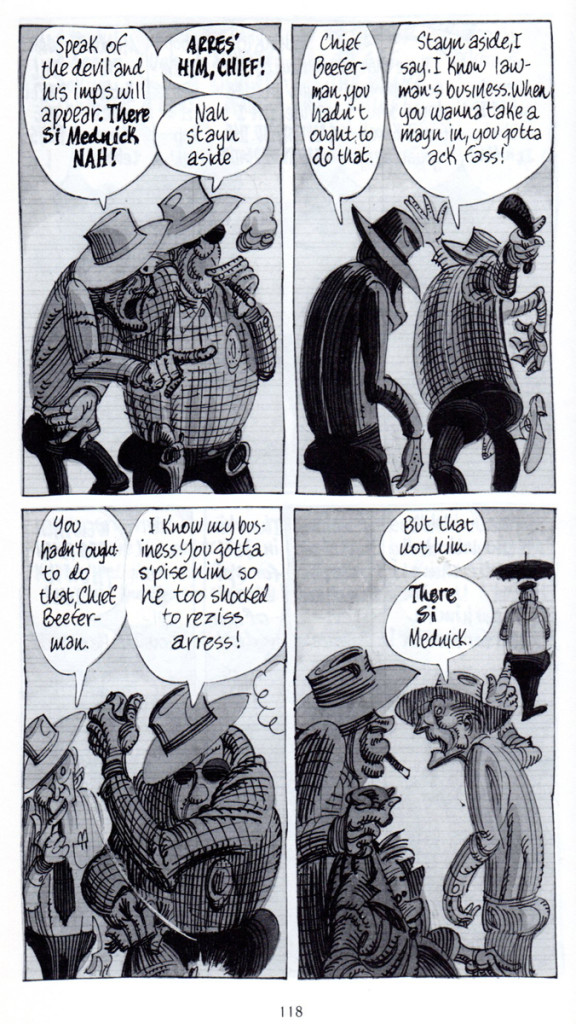

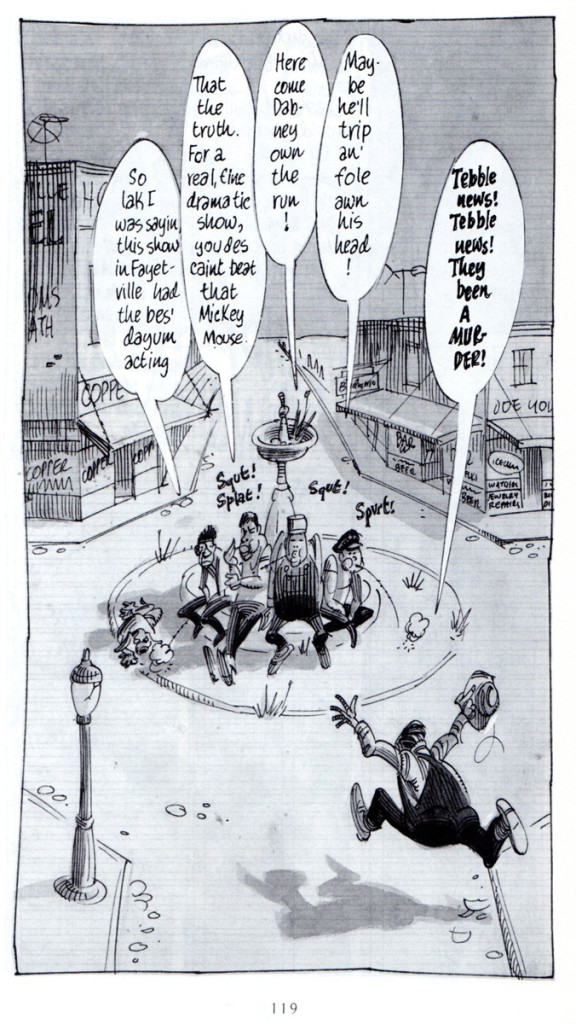

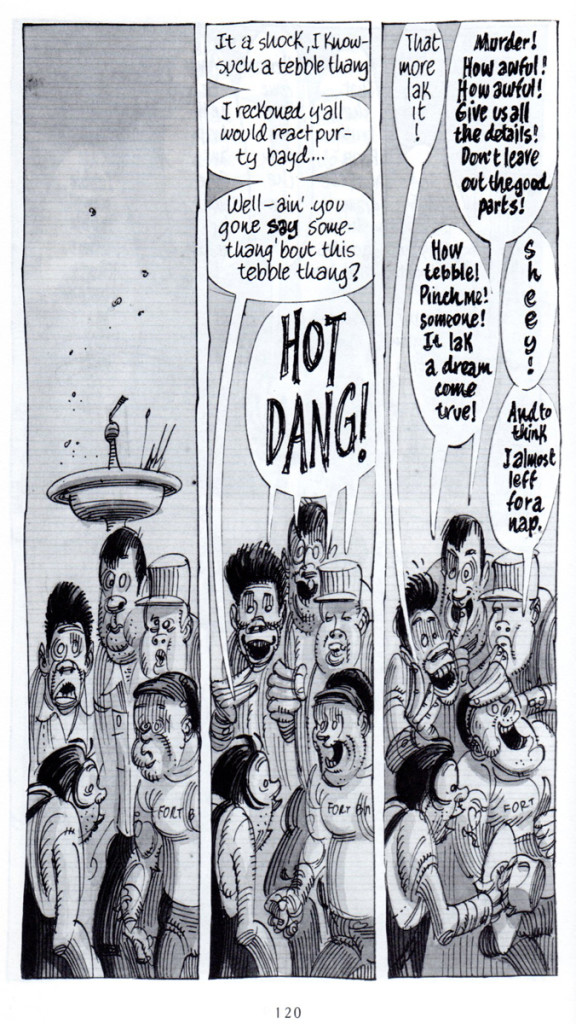

Kurtzman Jungle Book – part 1

- Currently, the Society of Illustrators is featuring an exhibit celebrating the art of Harvey Kurtzman. This exhibit continues through May 11th.*

- Currently, the Society of Illustrators is featuring an exhibit celebrating the art of Harvey Kurtzman. This exhibit continues through May 11th.*

When I brought this info to the attention of Bill Peckmann, Bill naturally began by sending me some pages of “Jungle Book”. It’s 4 pages long, so we’ve decided to break it into two. The second part will come next Friday. Here’s part 1, immediately following Bill’s comments:

- Harvey Kurtzman‘s “Jungle Book” was a very rare treat for us knuckle headed Kurtzman fans when it came out in 1959. It was 140 long pages of Harvey’s writing and art. The art was the rare part, since HK had just come off editing and writing Mad, Trump and Humbug magazines where the final art was always left to his “usual gang of Idiots”.

Here in this wonderful paperback was the master at the height of his cartooning talent! The treat was extended when Kitchen Sink Press published their reprint version in 1988, and what an exquisite job they did!

The cover of the book is the original paperback, the inside pages are from the beautifully done reprint book.

* Thanks to Steve MacQuignon for word on the show at the Society of Illustrators.

Bill Peckmann &Books &Illustration 21 Mar 2013 04:12 am

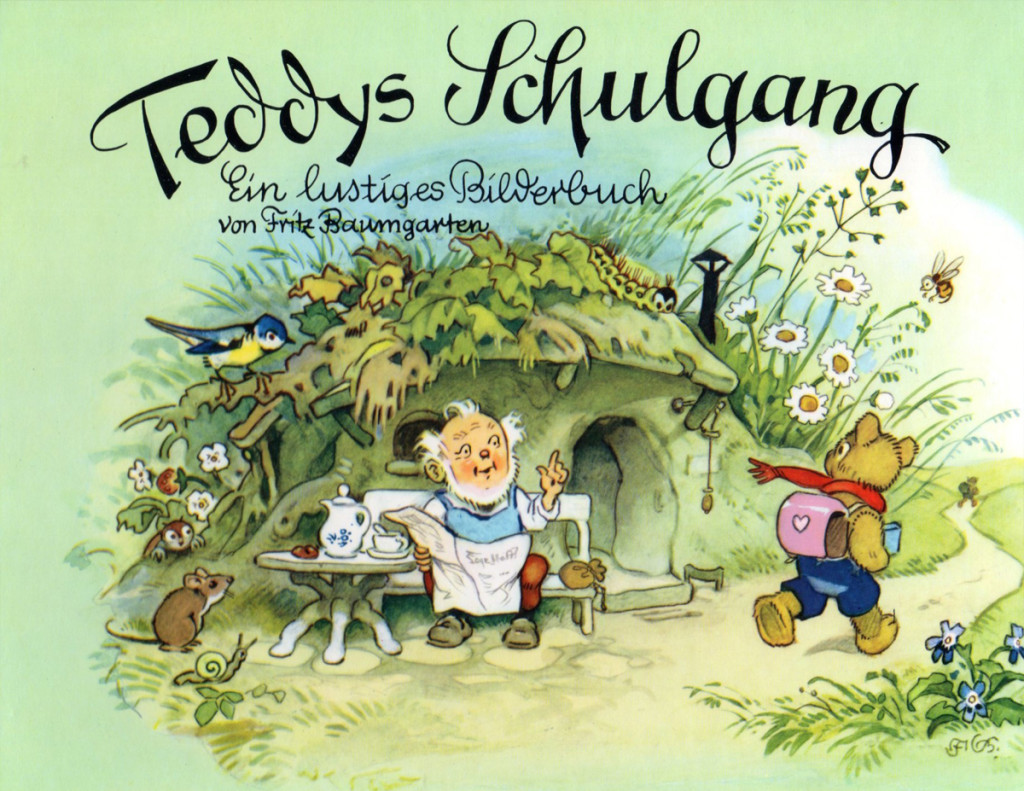

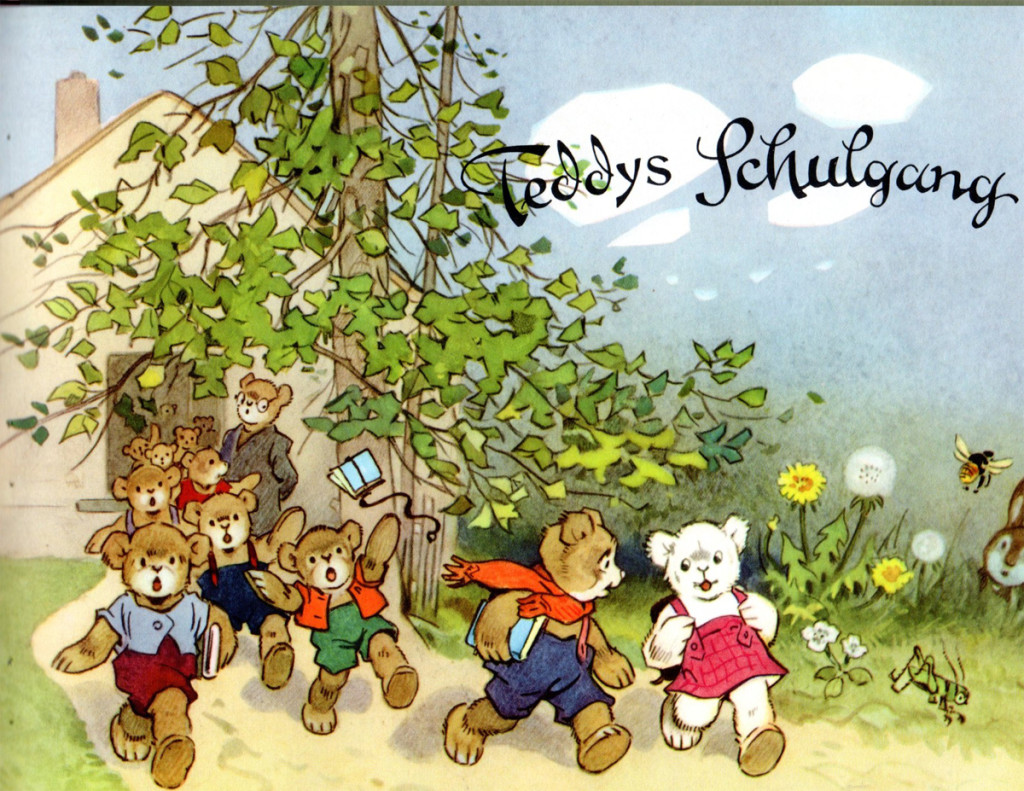

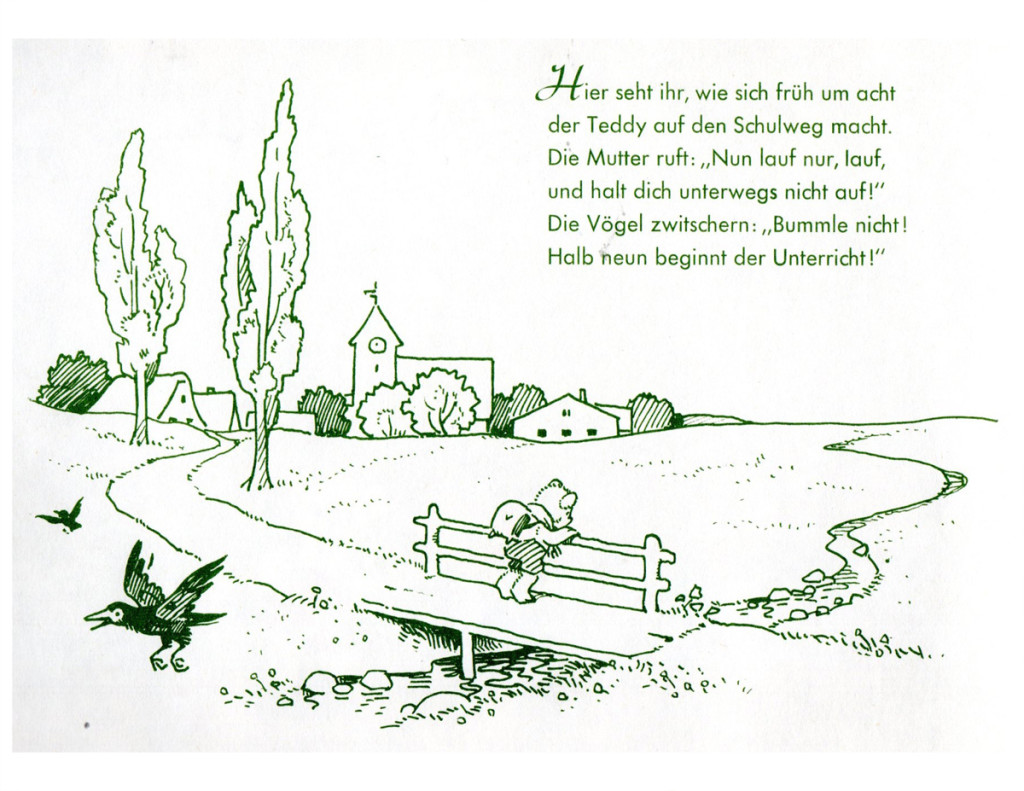

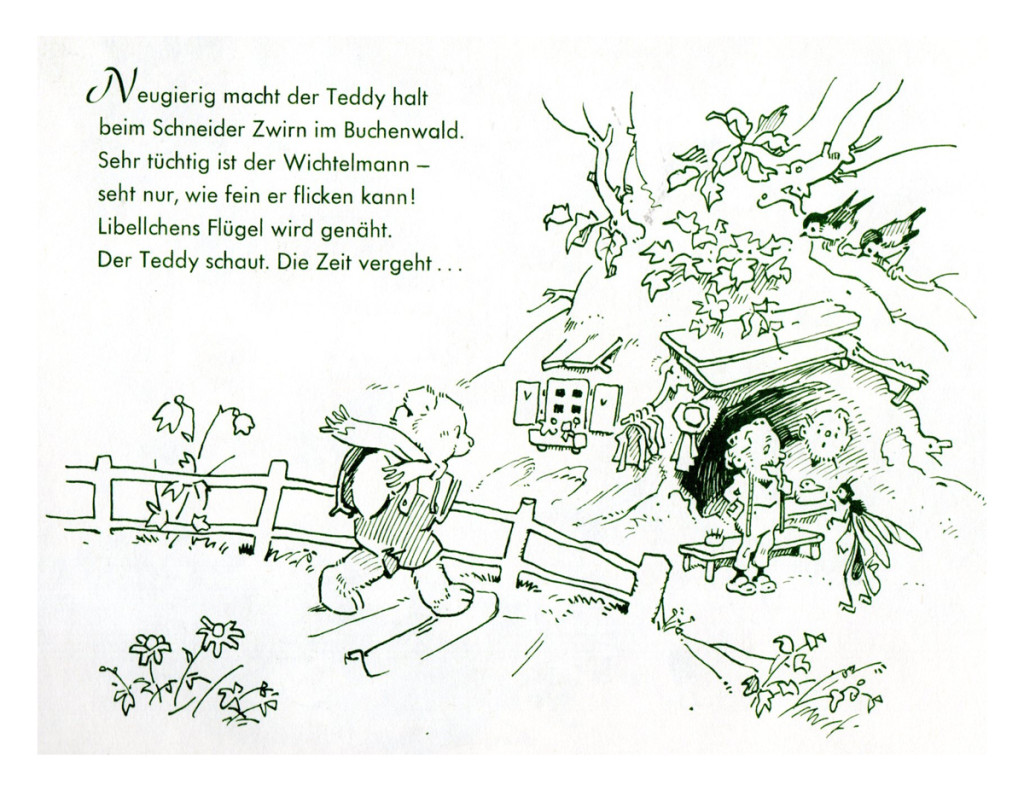

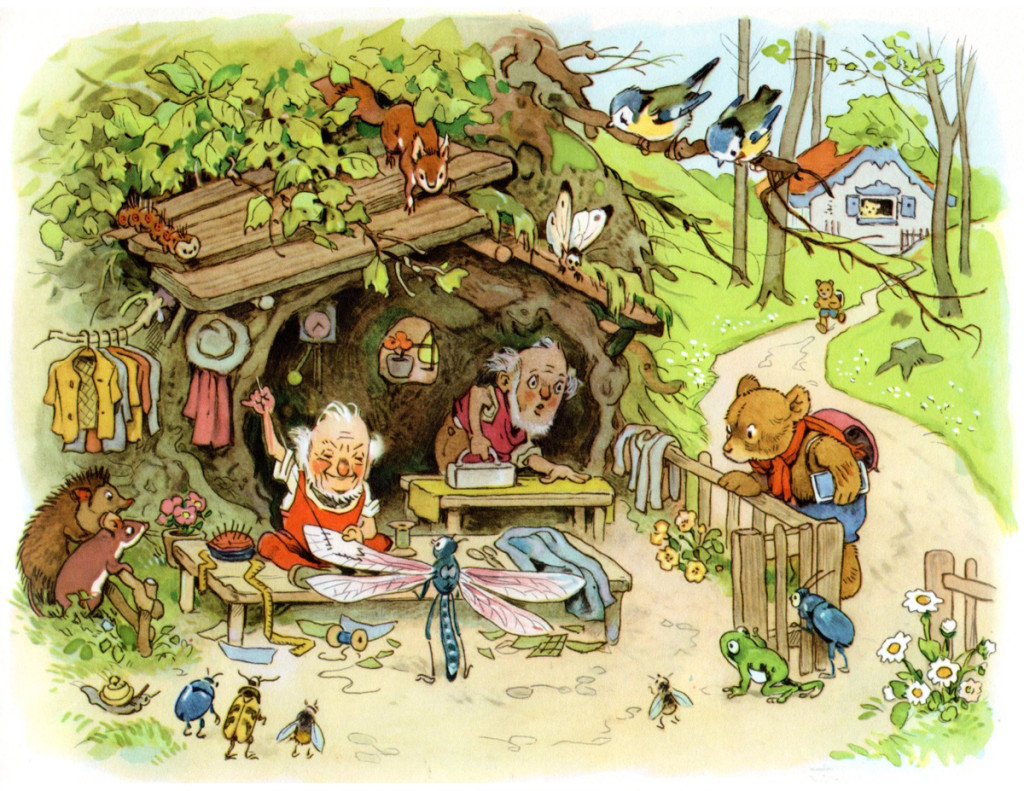

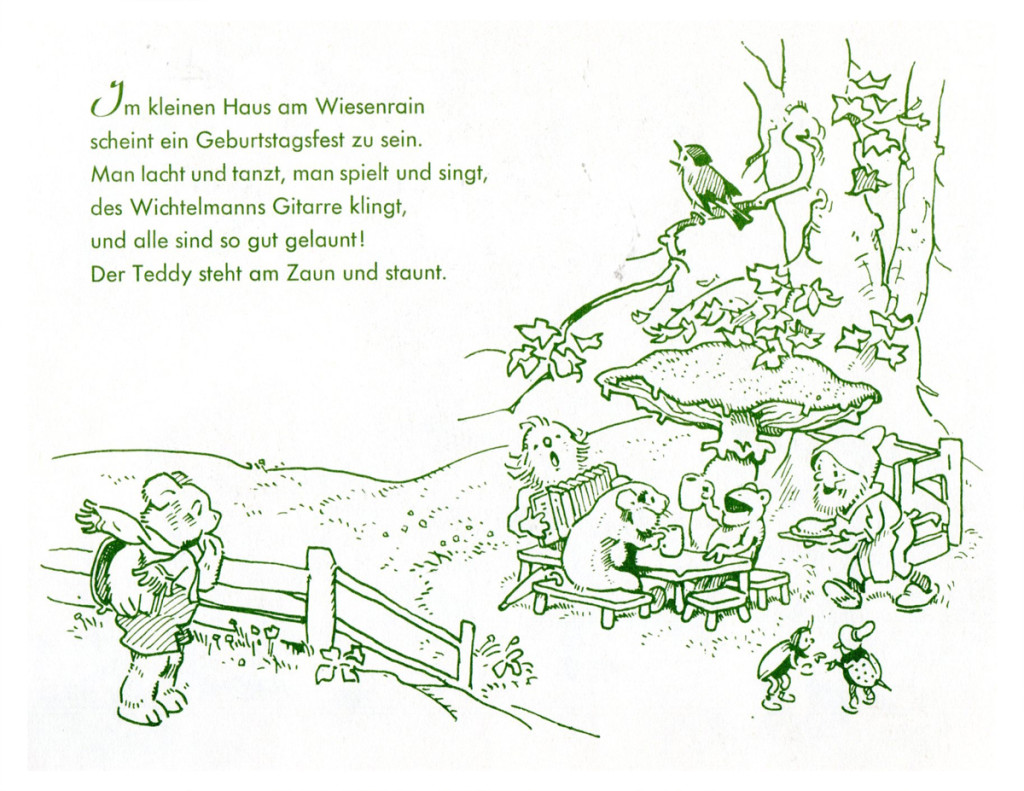

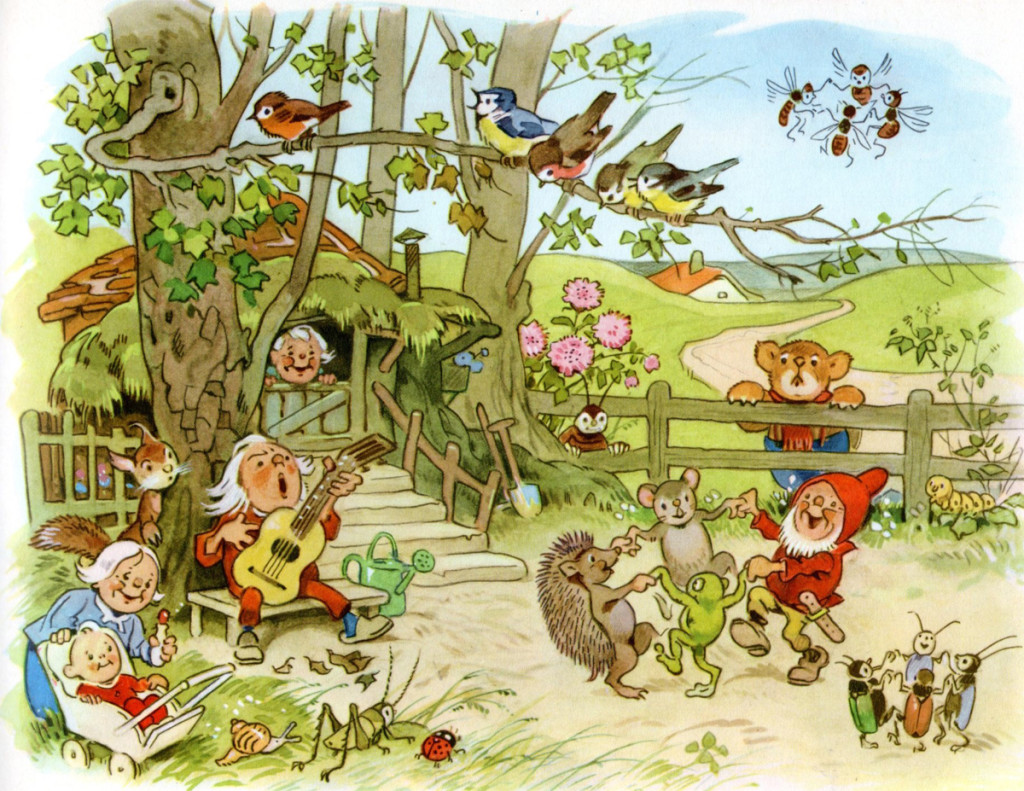

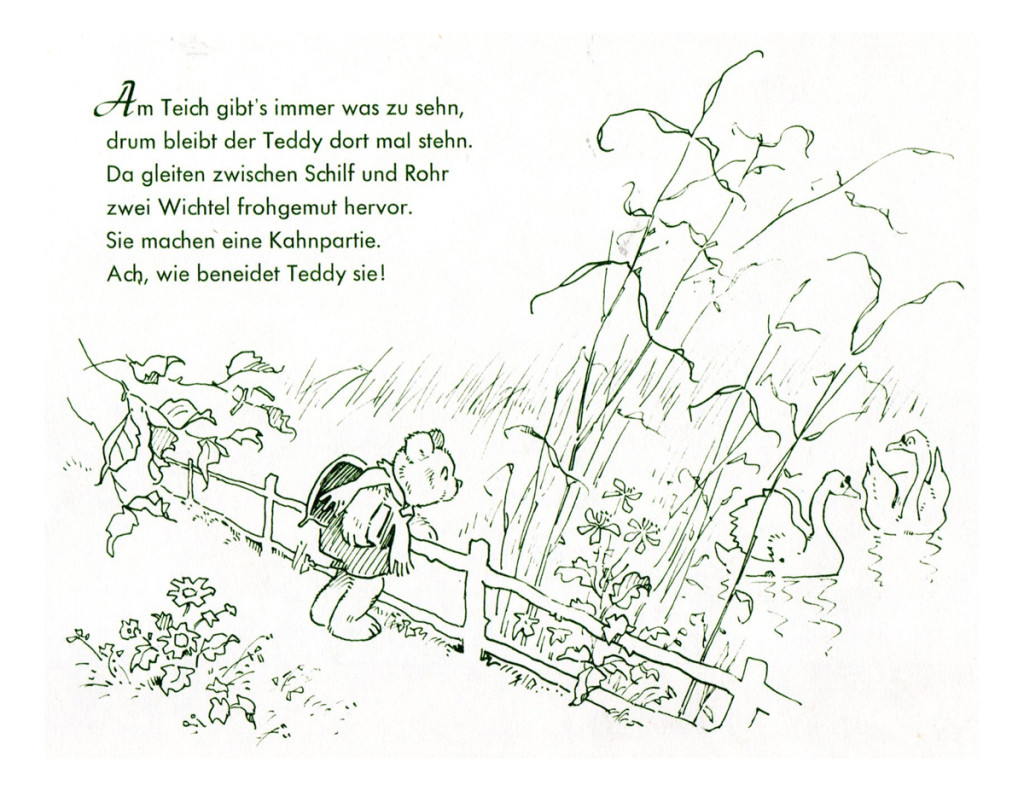

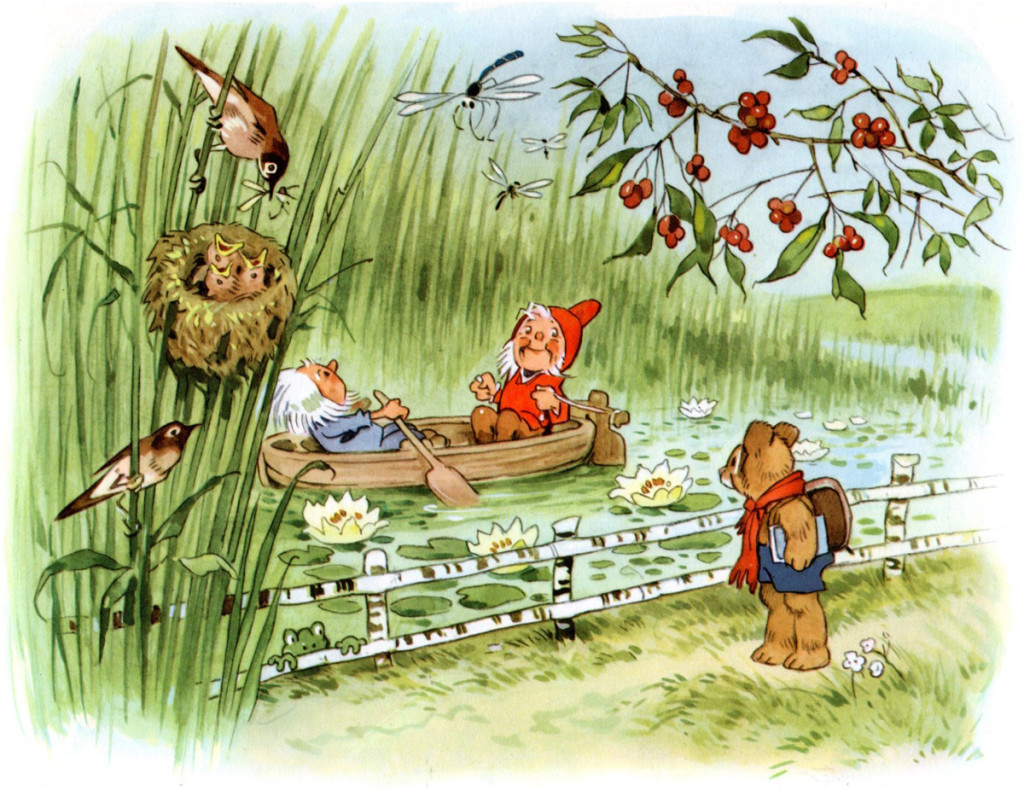

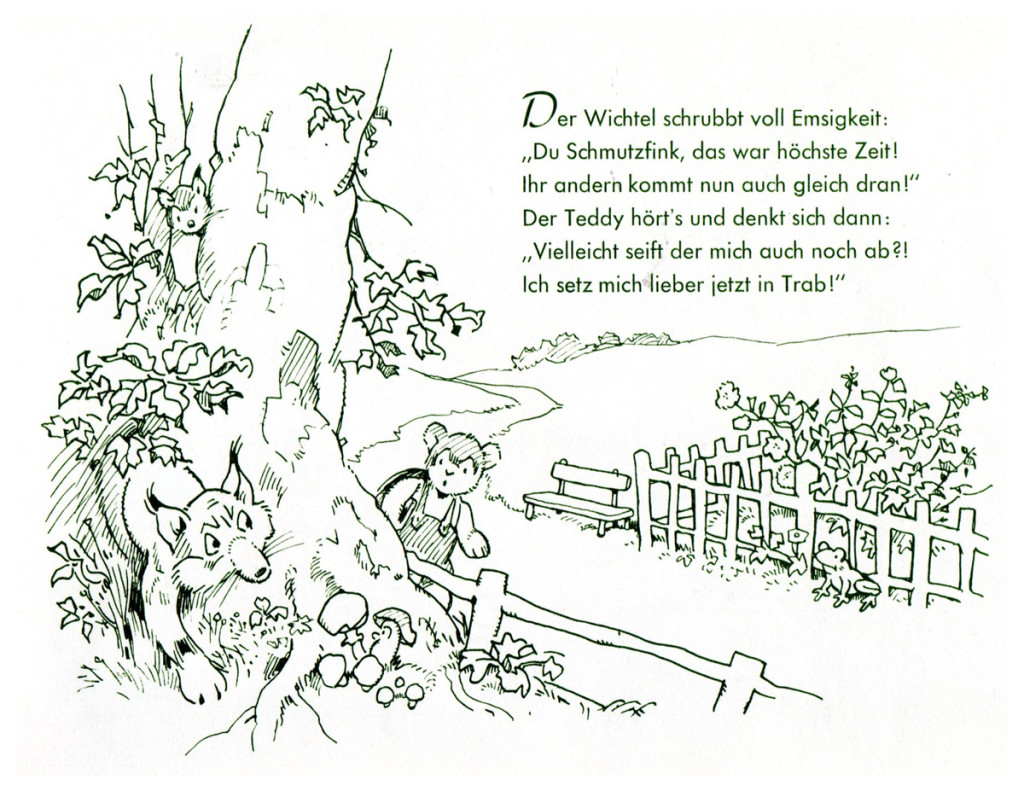

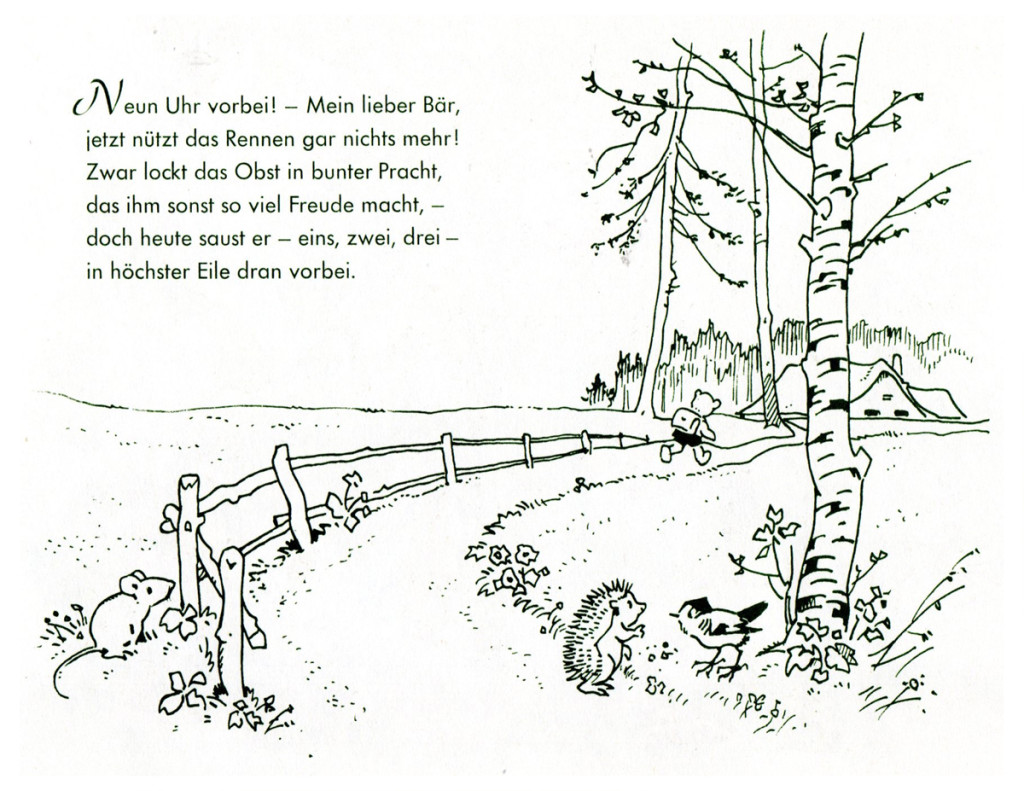

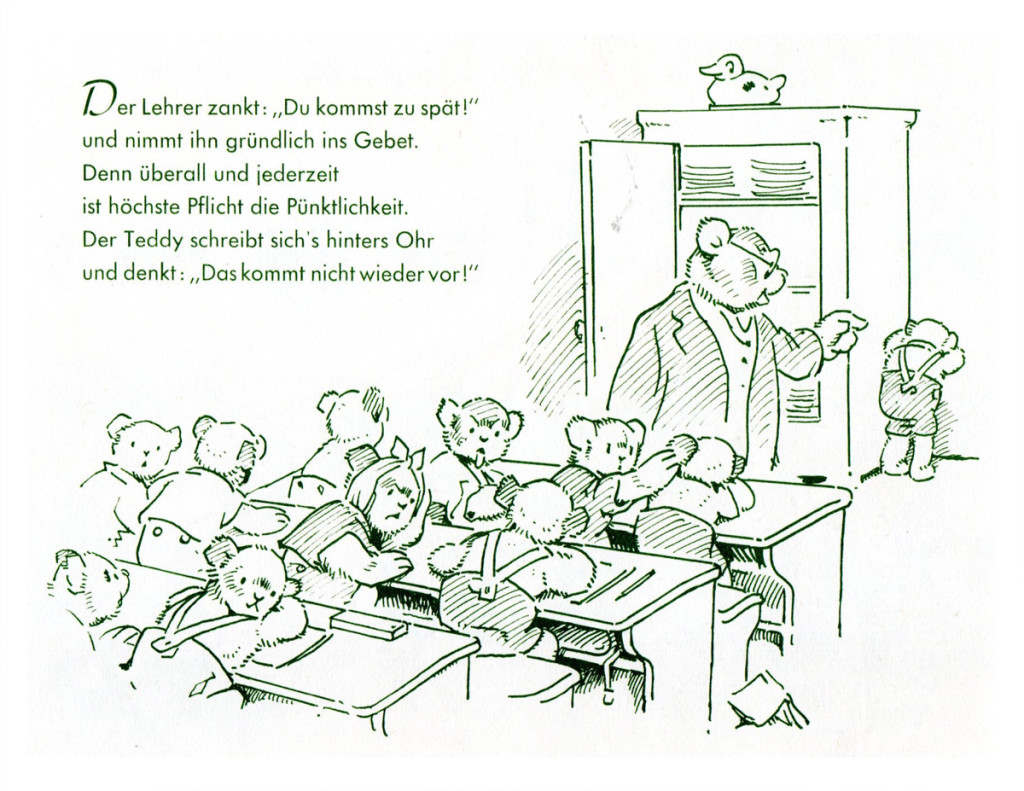

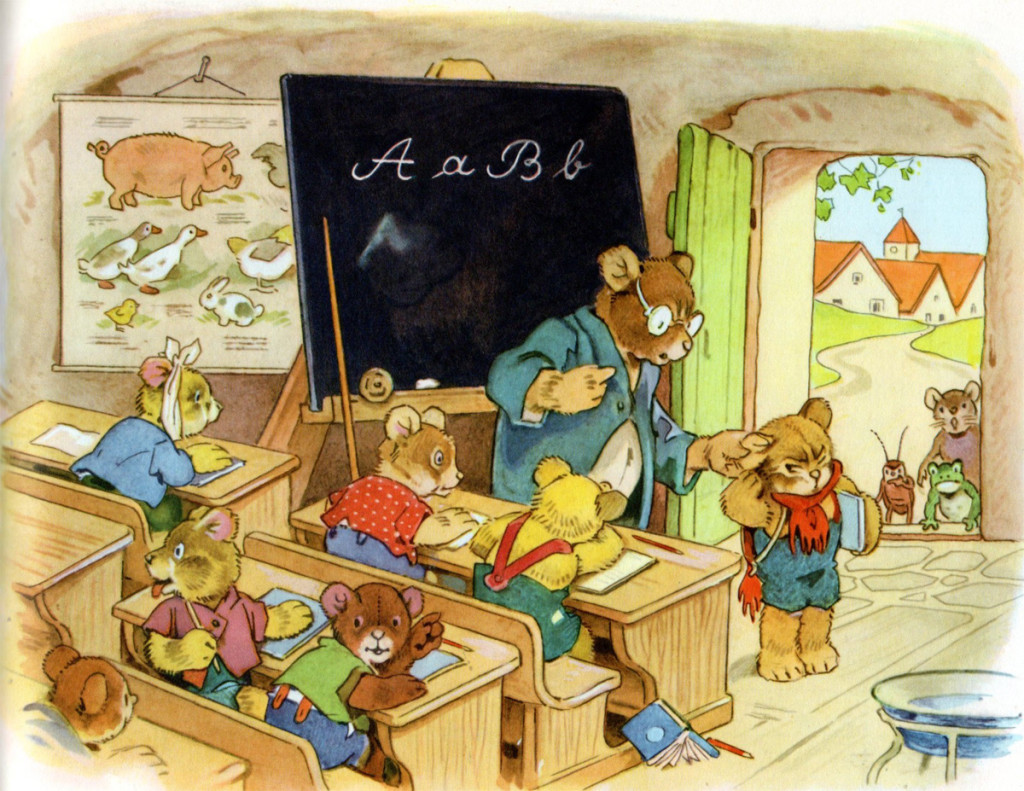

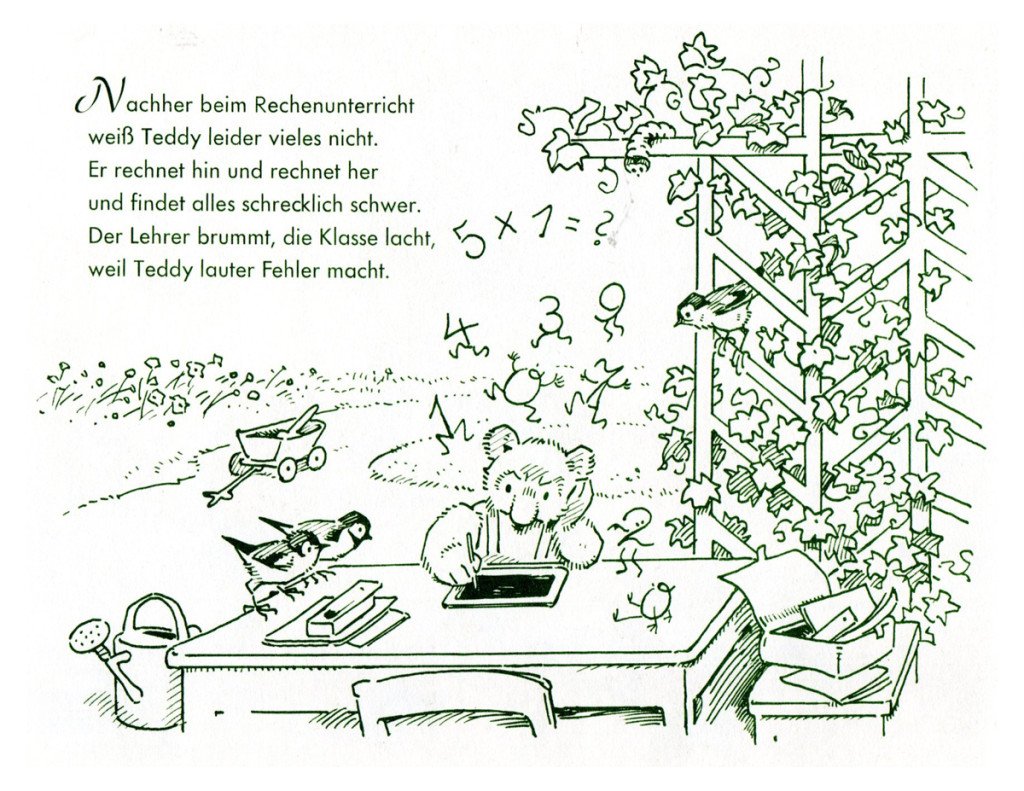

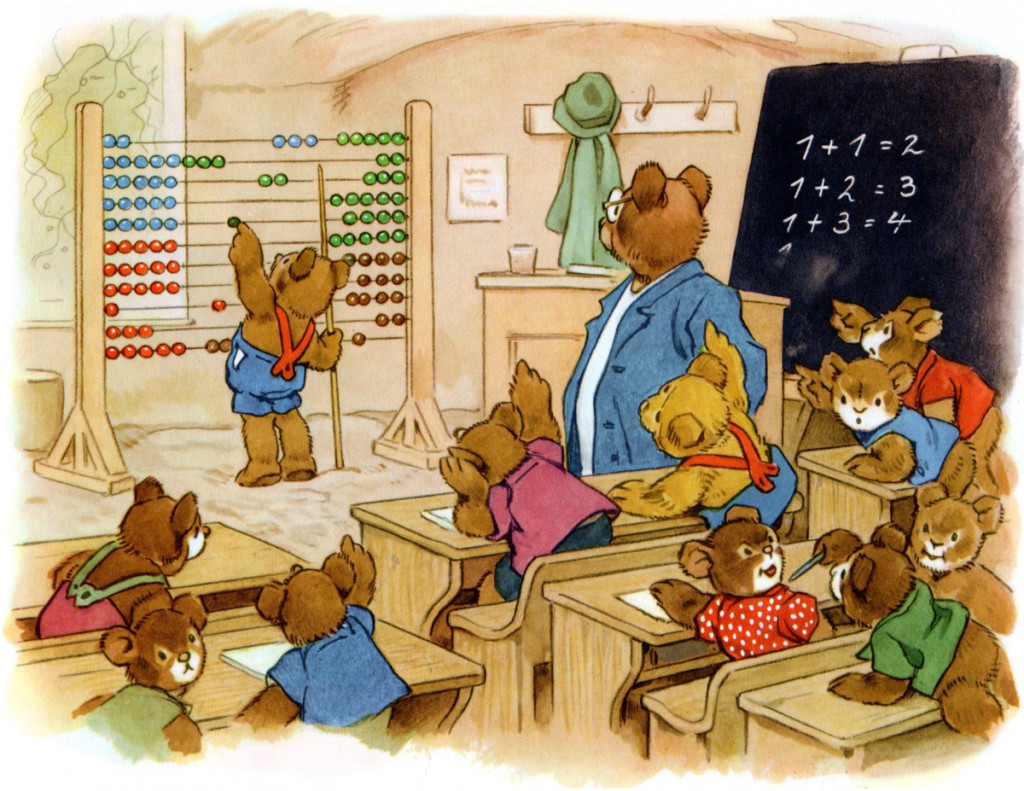

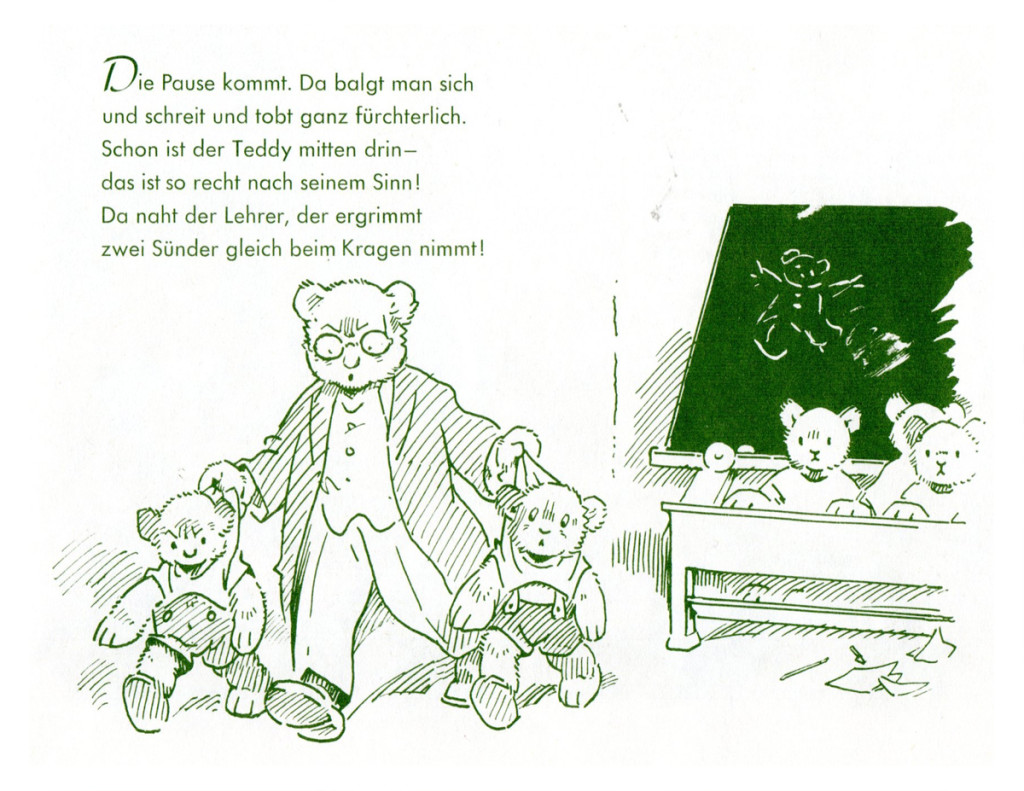

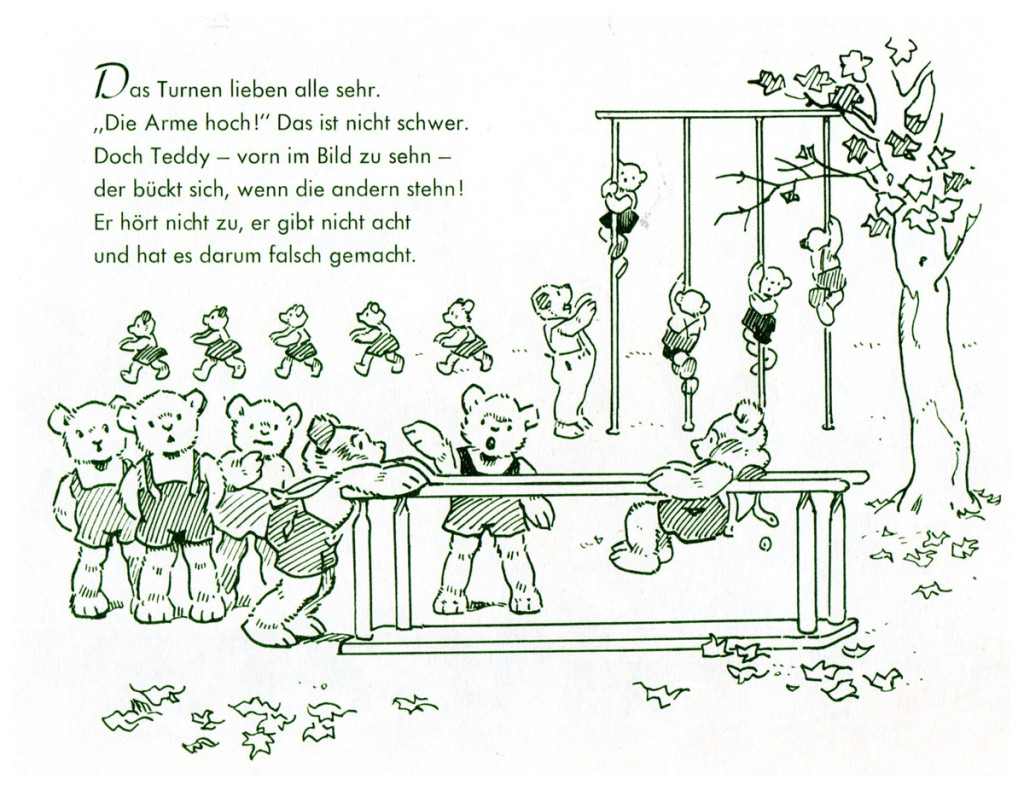

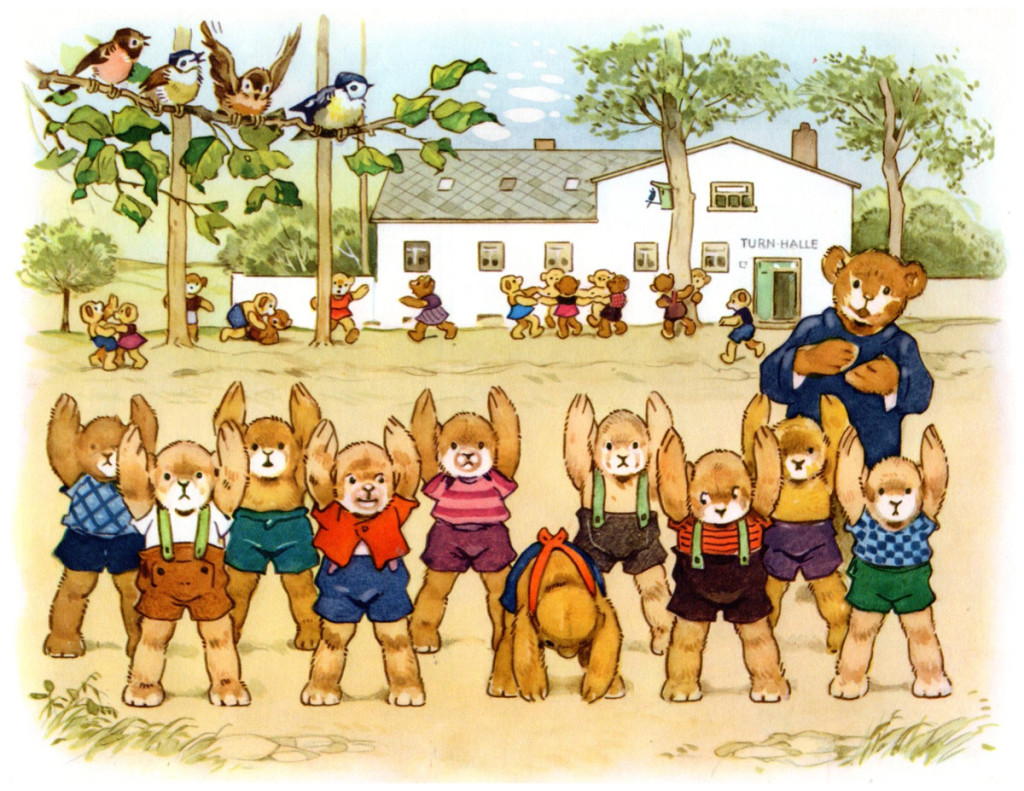

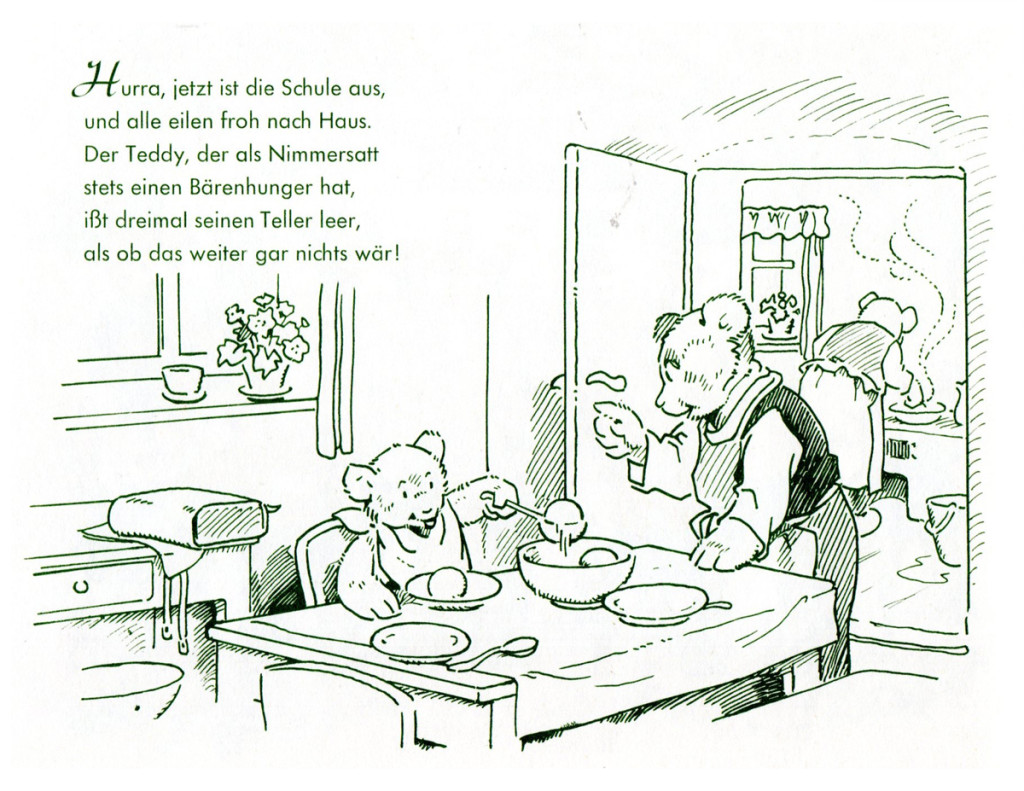

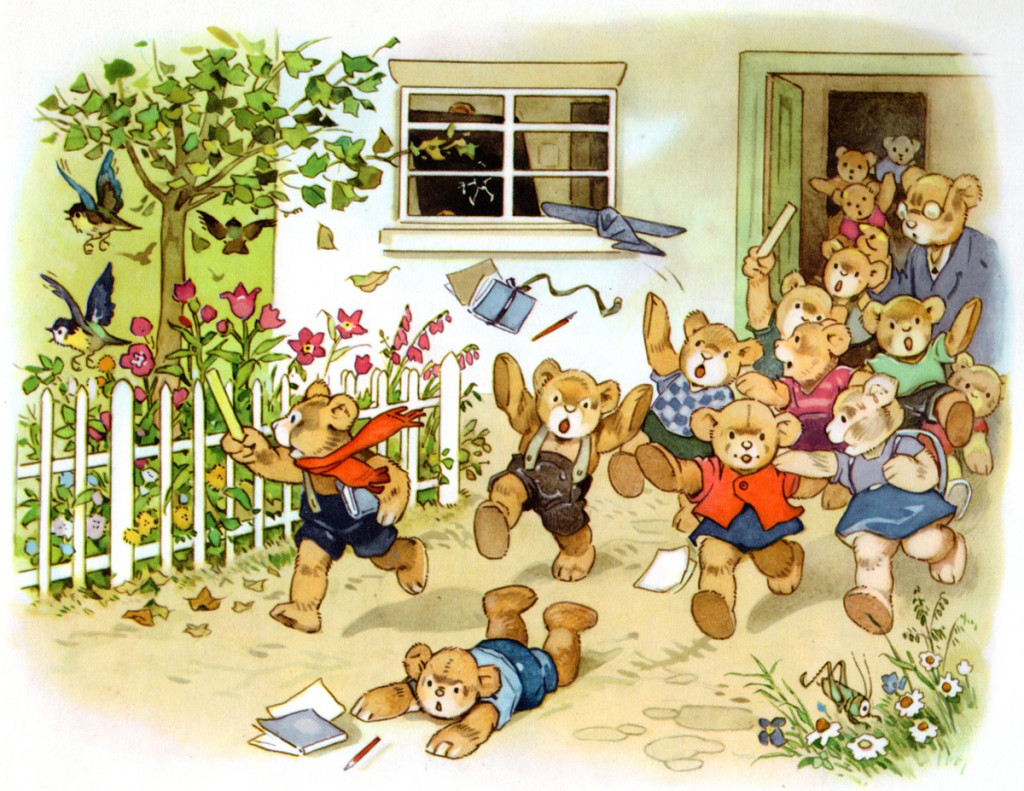

Baumgarten’s Toddy

Articles on Animation &Books 04 Mar 2013 05:49 am

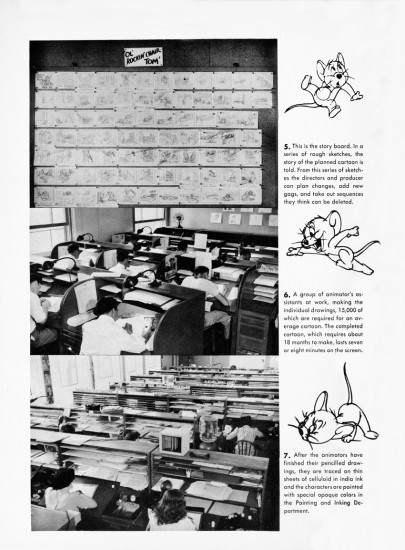

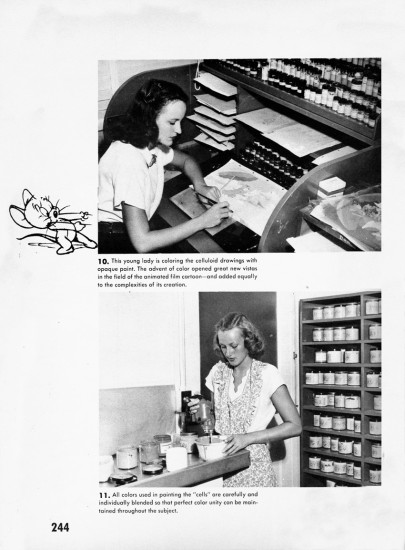

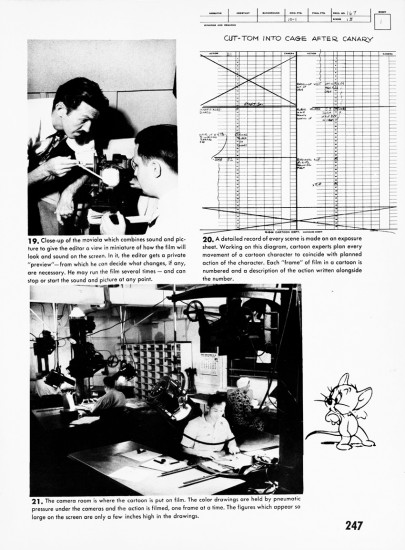

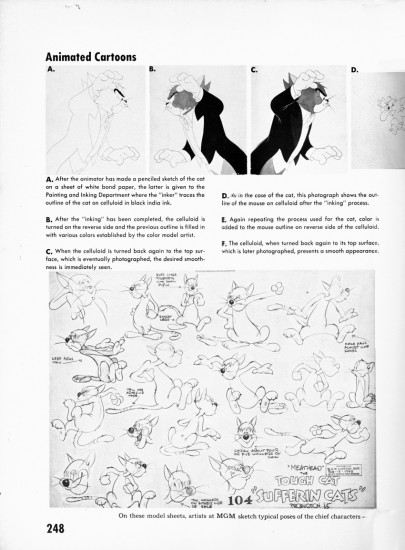

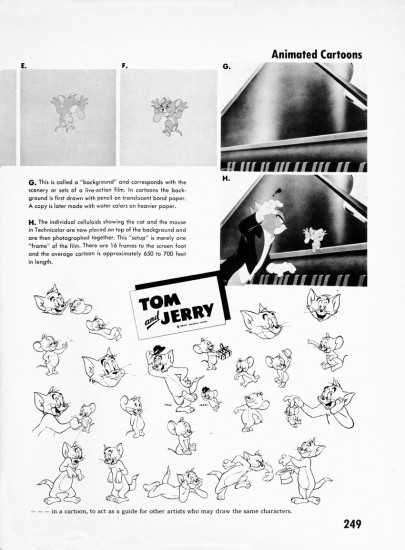

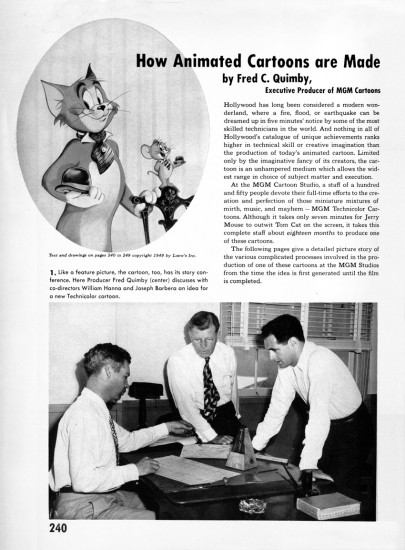

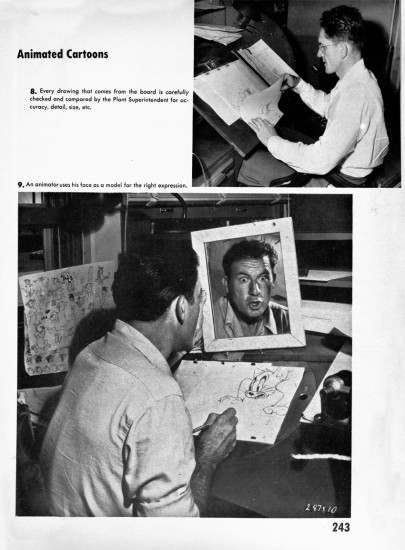

The MGM Cartoon Studio

- When I was a kid the only animation books available were few and far between. Fortunately, I lived near a local library that stocked many of these books (6-10 of them, including the great book by R.D. Feild, Art of Walt Disney). One that I loved was this book by Gene Byrnes, The Complete Guide to Cartooning. It had a full chapter on the MGM cartoon studios and credits Fred Quimby as writer of the chapter. The book was a strong inspiration for me when back then, and it still sends a chill up my back and gets me wanting to animate when I look at a couple of those images.

- When I was a kid the only animation books available were few and far between. Fortunately, I lived near a local library that stocked many of these books (6-10 of them, including the great book by R.D. Feild, Art of Walt Disney). One that I loved was this book by Gene Byrnes, The Complete Guide to Cartooning. It had a full chapter on the MGM cartoon studios and credits Fred Quimby as writer of the chapter. The book was a strong inspiration for me when back then, and it still sends a chill up my back and gets me wanting to animate when I look at a couple of those images.

The cartoon Cat Concerto is featured. Obviously the studio was pushing it for the Oscar, and a bit of publicity, appearing in this book, didn’t hurt. It did win the Oscar. The other five nominees included:

- Musical Moments from Chopin (Lantz, Dick Lundy dir)

Walky Talky Hawky (WB, Rob’t McKimson dir)

Squatter’s Rights (Disney, Jack Hannah dir)

John Henry and Inky-Poo (Par, Georg Pal)

3 cartoons featuring classical piano performances by the star cartoons character. Very interesting. This is the subject of the debate on-going at several sites.

Thad Komorowski brought up the controversy and discusses it n full. The debate of whether one short ripped off another actually started back in 1946.

Michael Barrier discusses the discussion adding some information.

Jerry Beck offers some historic material. just now. Watch the cartoon on Thad’s site.

If you recognize anyone in the photos and can identify anyone , please leave a comment.

1

1(Click any image to enlarge.)

Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera are on opposite sides of the table.

Producer, Fred Quimby is in the middle.

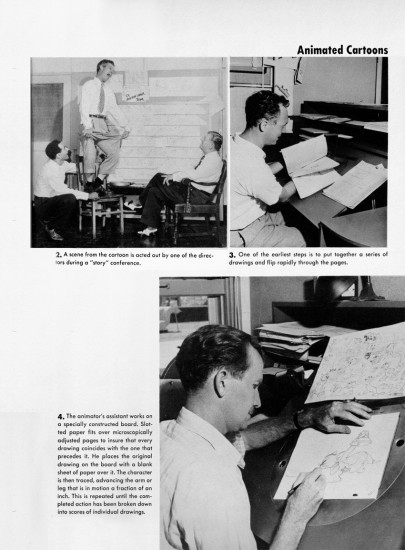

2

2

#3 Upper right: Preston Blair / #4 Bottom: Asst Animator Tom McDonald

4

4

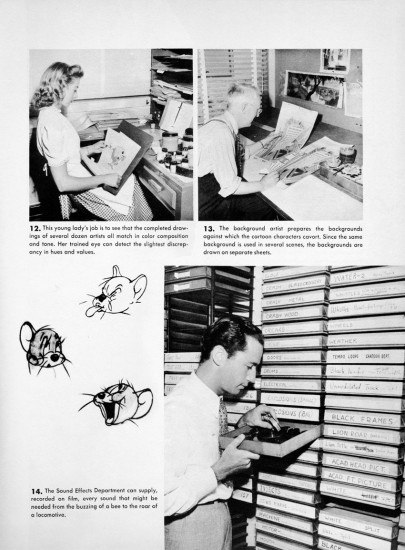

#8 Upper: Max Maxwell head of checking / #9 Bottom: Irv Spence, animator

6

6

#13 is Johnny Johnson, BG painter

7

7

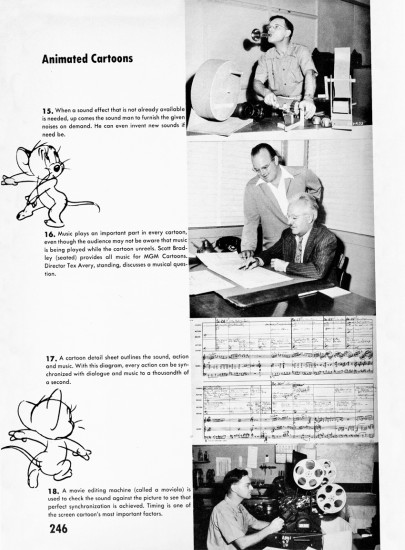

#16 Middle: (standing) Tex Avery with (seated> composer Scott Bradley

I’m enlarging the photo of the storyboard. Without the benday pattern and at a higher res, it’s a little easier to read blown up.

This book also includes some pretty great (non-animation) cartoonists. I still remember every page from my childhood when I borrowed this book countless times from my local public library.

Articles on Animation &Bill Peckmann &Books 28 Feb 2013 04:08 am

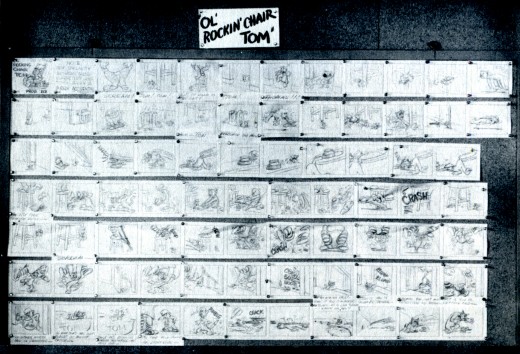

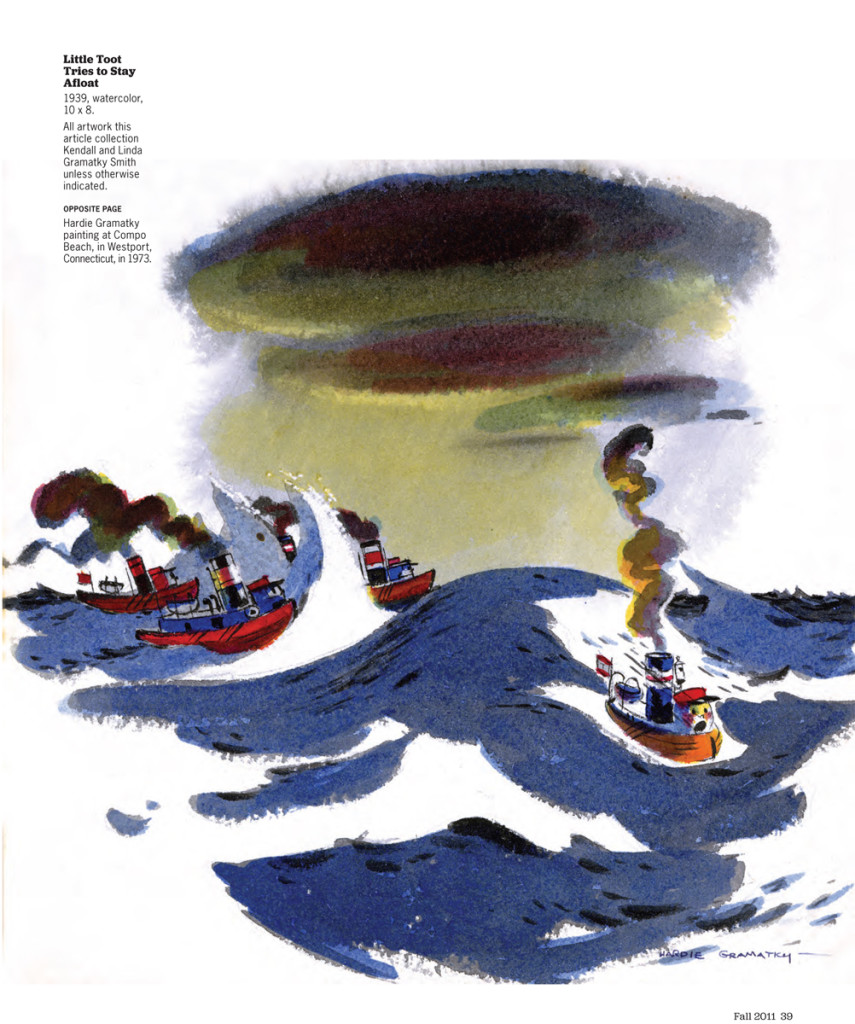

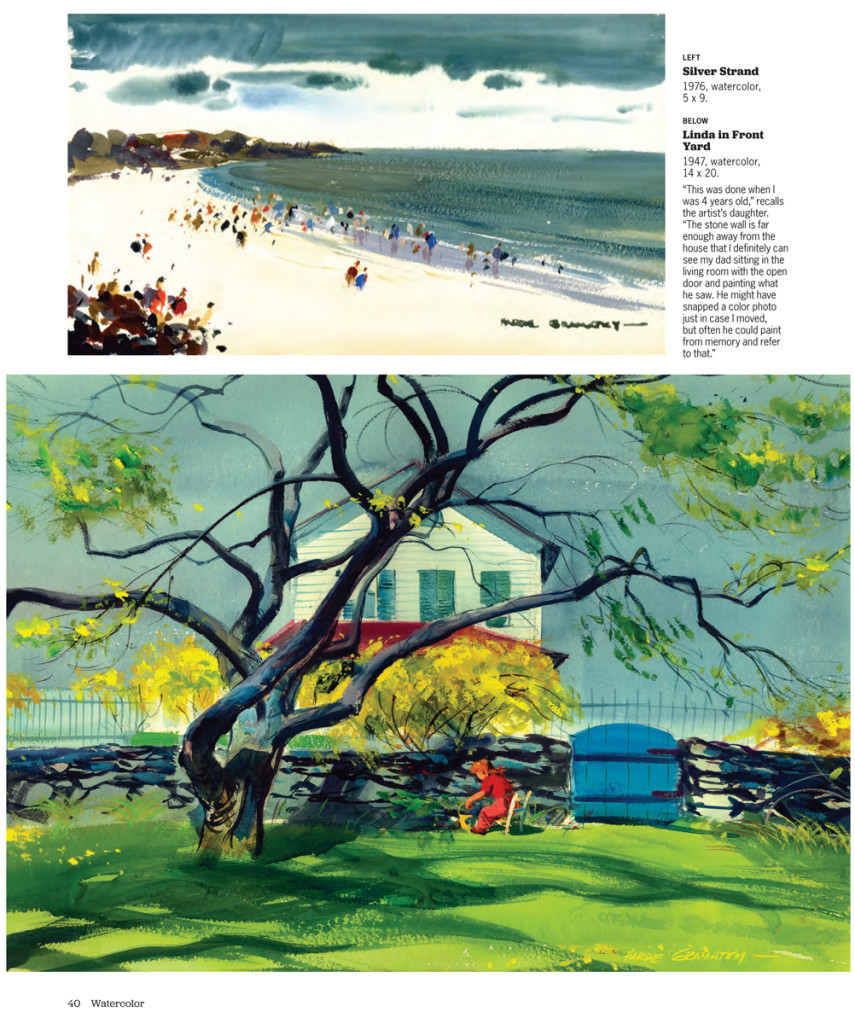

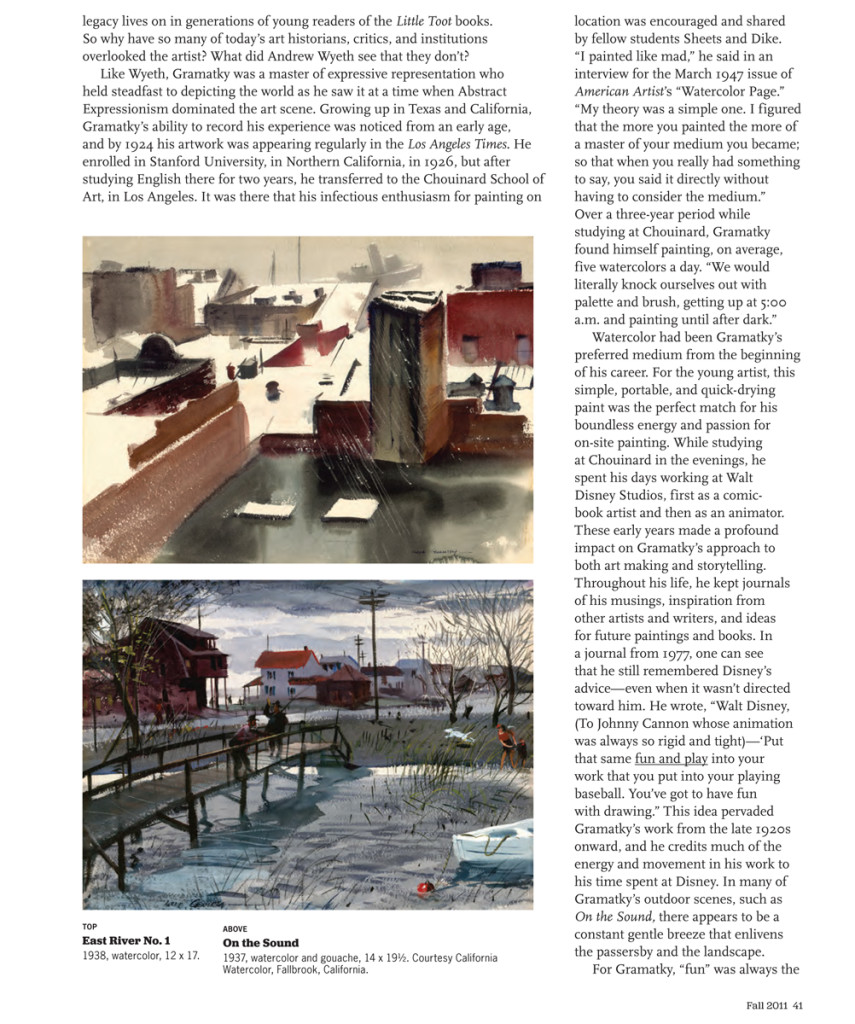

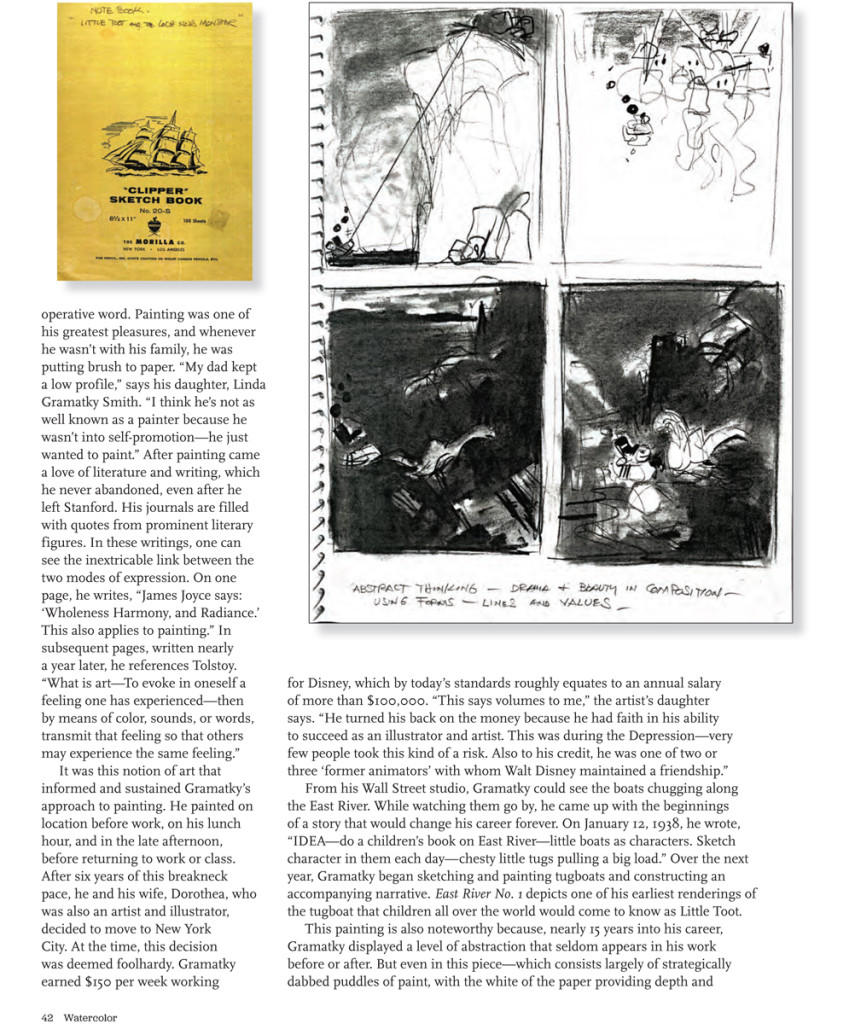

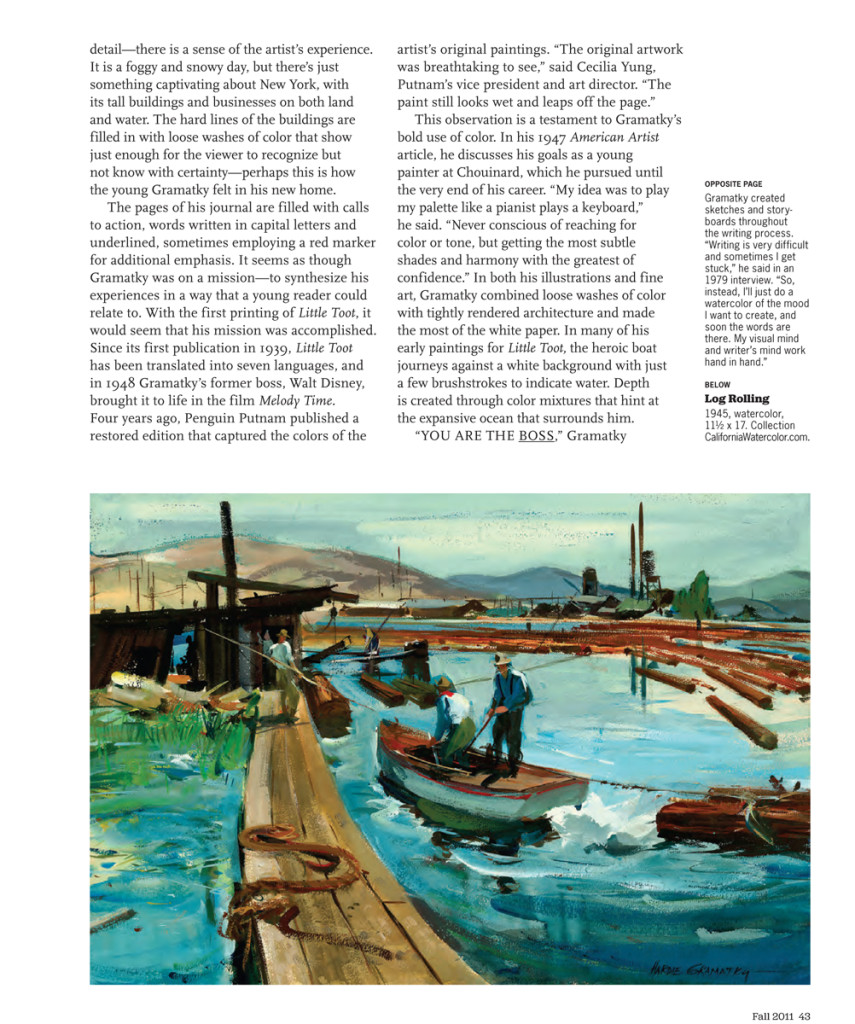

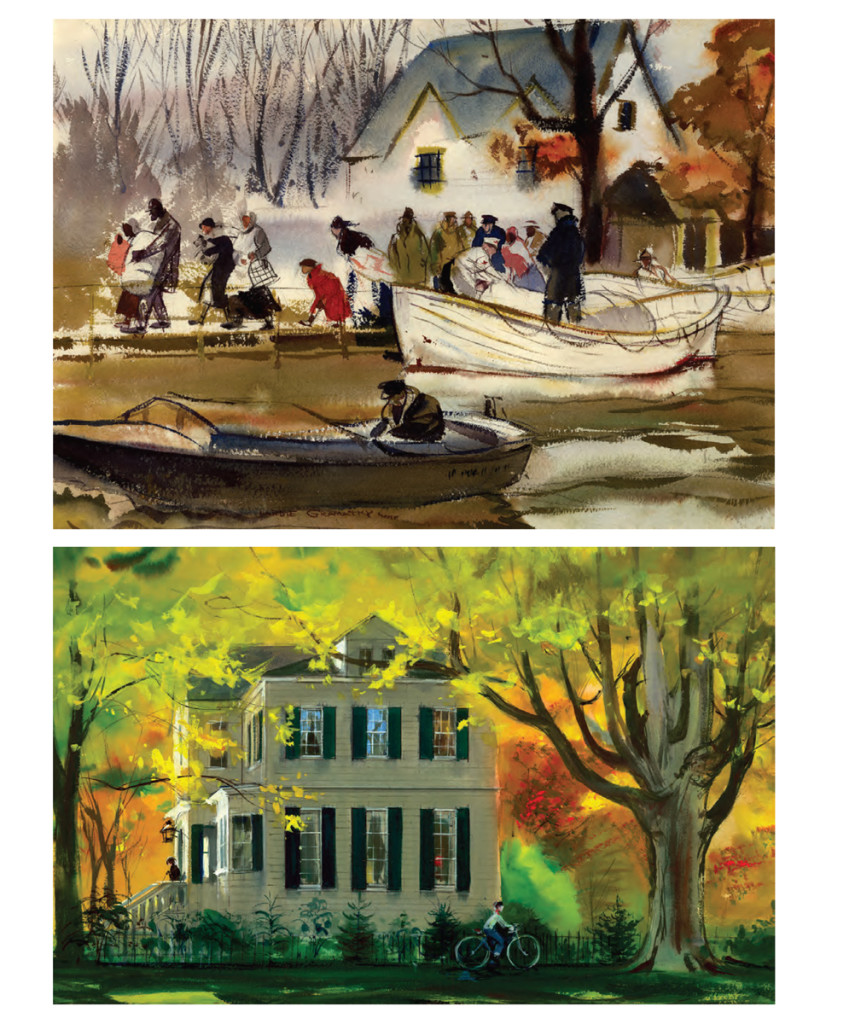

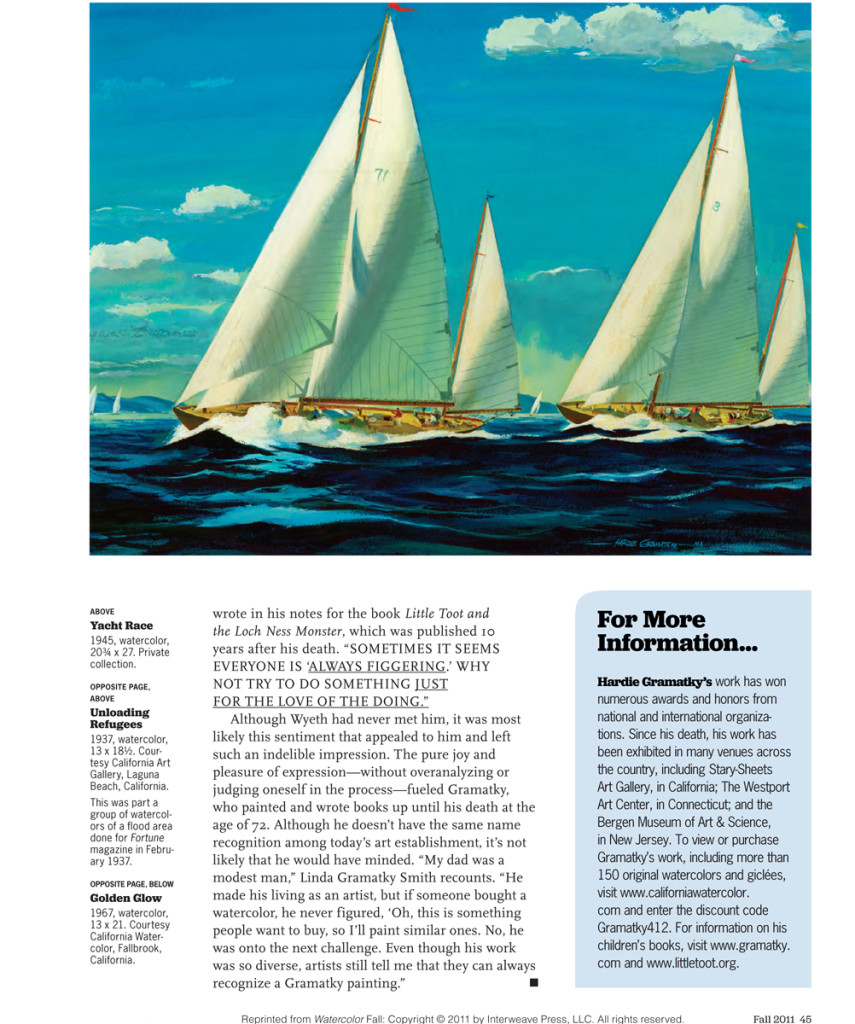

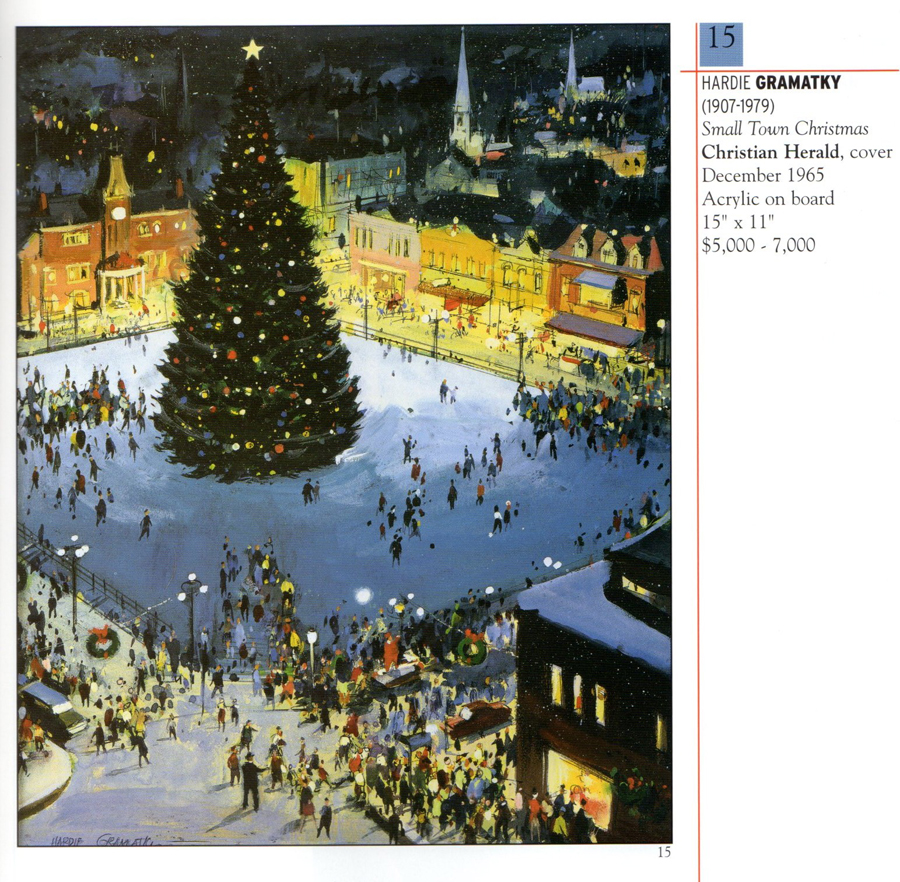

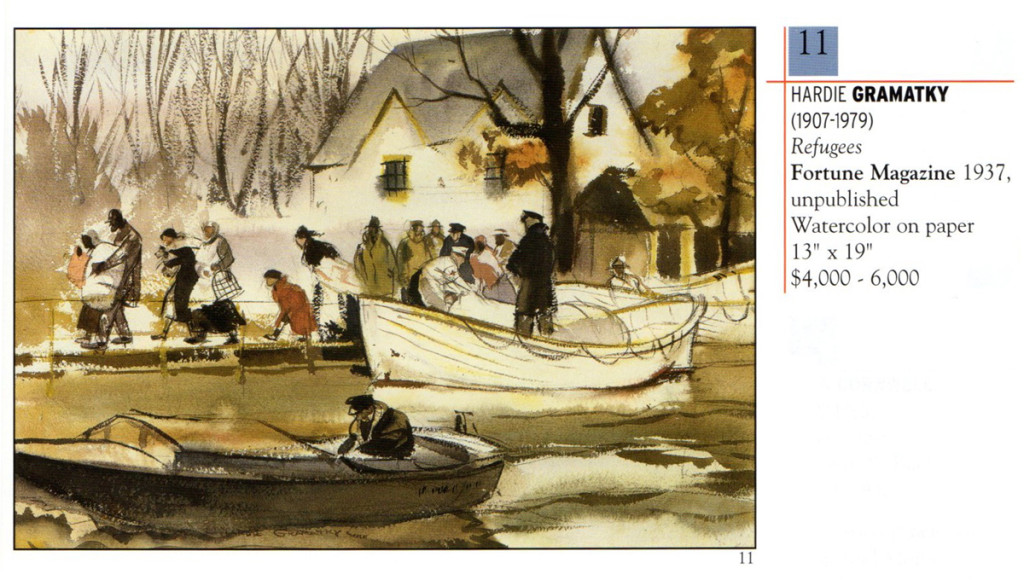

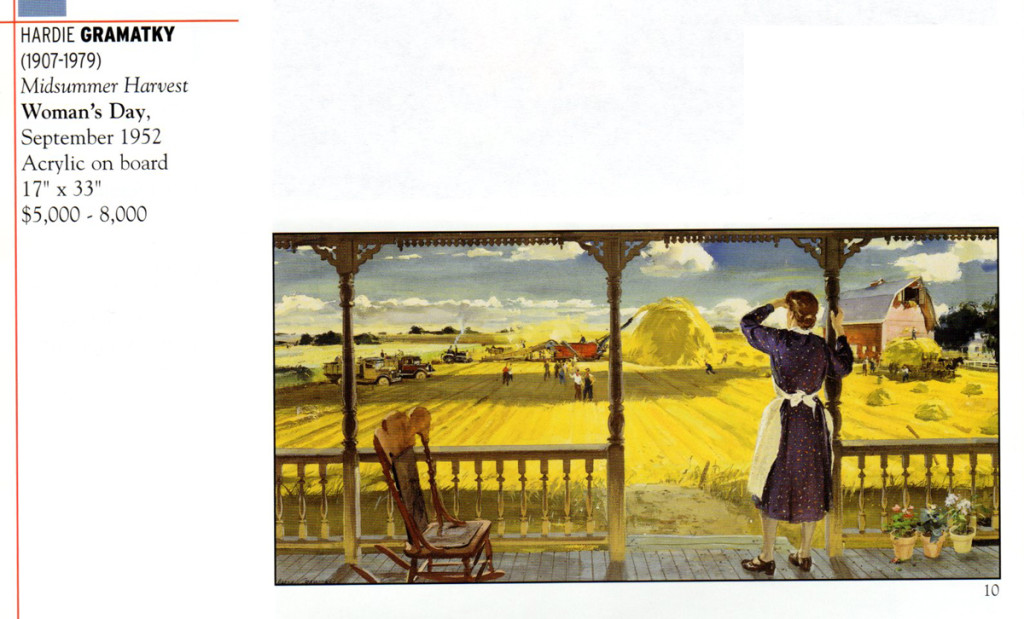

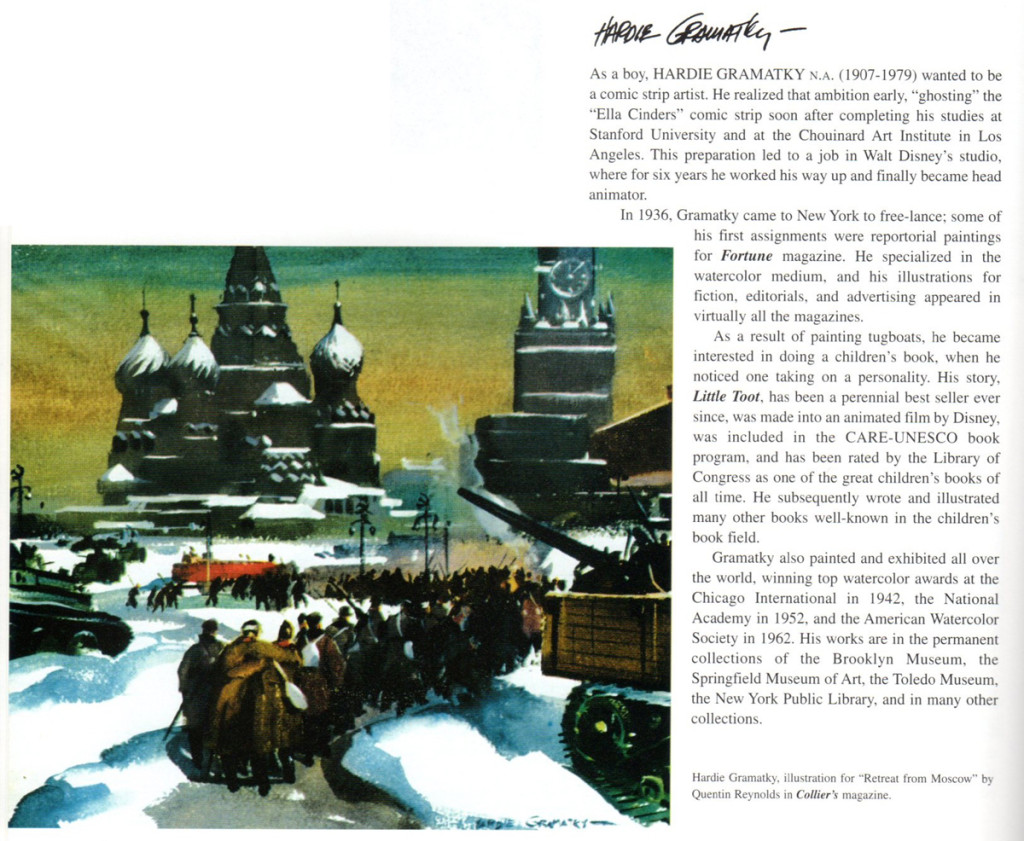

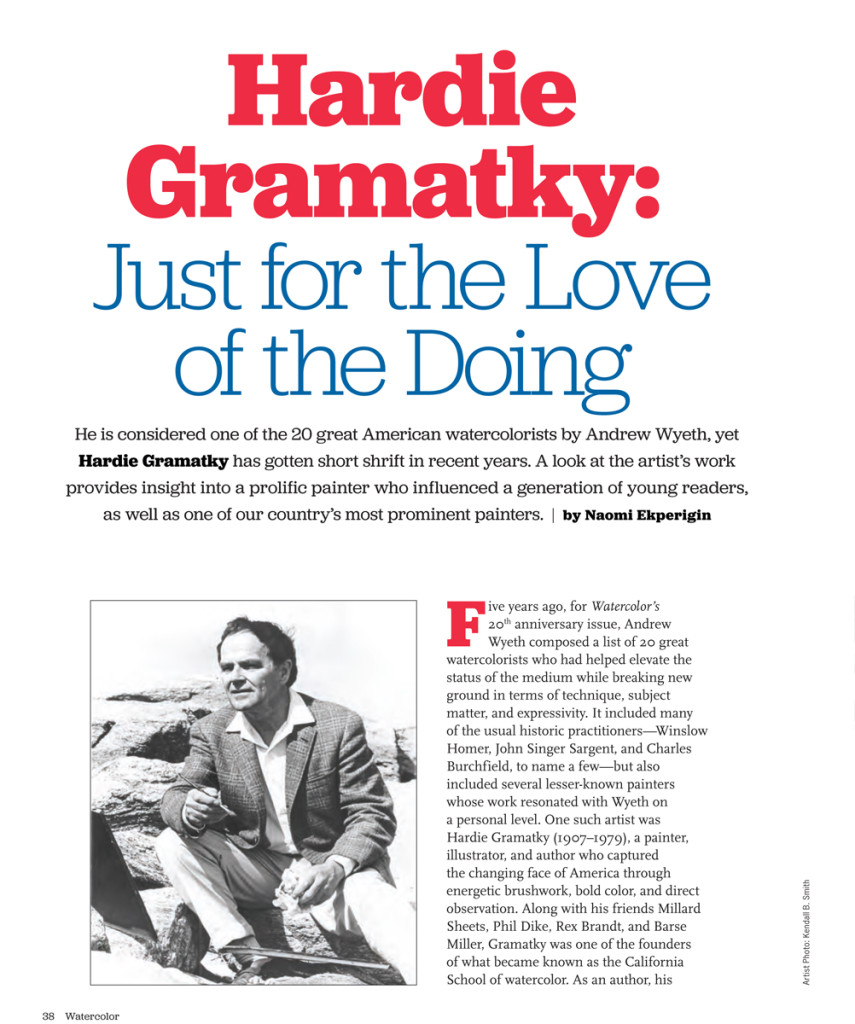

Hardie Gramatky’s Art

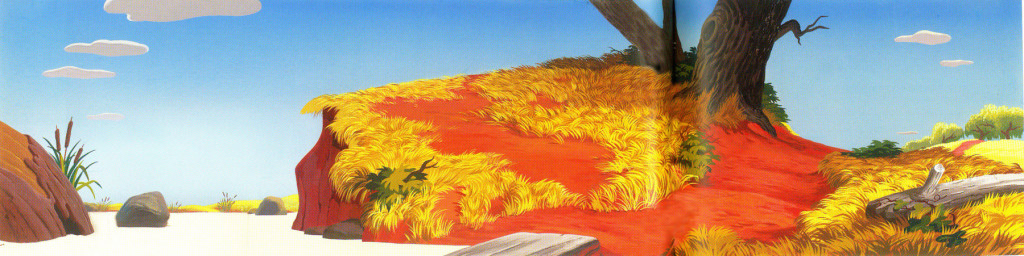

- One of Disney’s early animators who left the studio before it went through its renaissance into the features, was Hardie Gramatky. He came to the studio from Chouinard and had been a brilliant watercolorist even when he entered the studio. While working at Disney by day, he continued to study art at Chouinard by night. After leaving Disney, he focused on his art acting as something of a force in developing the California School of Watercolor, At the same time he did children’s books to earn money. His great claim to fame was the famous children’s book, Little Toot, which, itself, was animated by the studio as part of the feature compilation, Melody Time. The short outlived the feature and has played often developing its own legacy.

Bill Peckmann had sent me this article from Watercolor Magazine, the Fall/2011 issue.

1

1

Bill Peckmann also included clips from this Society of Illustrators, Benefit Centennial Auction, which included the following pieces by Gramatky;

Magazine cover

To get an idea of scenes Gramatky animated at Disney’s here are links to some past drafts that I’ve posted:

Dognapper, The Whoopee Party, Mickey’s Good Deed, The Robber Kitten

The children’s book, Little Toot is large enough that it has its own website.

Books &Commentary &Disney 19 Feb 2013 05:17 am

Jim Korkis’ Song of the South

As the War came to an end, Walt Disney realized that he needed to find a way to raise money for his movies or, at the least, make films more profitably. One idea he chose to employwas to make more live action film.

As the War came to an end, Walt Disney realized that he needed to find a way to raise money for his movies or, at the least, make films more profitably. One idea he chose to employwas to make more live action film.

He’d had some modest success with The Three Caballeros and Saludos Amigos by combining live action and animation.

For years he’d thought of doing a combination film with Alice In Wonderland placing a live action Alice in an animated world, not unlike the early silent films Alice in Cartoonland.

Disney also thought of going to the stories of Joel Chandler Harris. By making the story of the humans in live action and the stories of Br’er Rabbit, Br’er Fox and Br’er Bear in animation, as told by Uncle Remus who would star in the significant part of the story told in live action. Thus he could easily work as the voice over narrator for the animation.

The film went into production in 1945 and pulled Disney down a harsh and difficult path.

Now, some 70 years later, studio head, Robert Iger, has vowed numerous times to keep Song of the South (the film’s title) on a shelf in the Disney vault, which is where it remains.

Disney historian, Jim Korkis, has written a series of excellent essays which act as chapter in a new book about the making and unmaking of this film. In his book, Who’s Afraid of Song of the South, a great weight of information completely informs us about this movie while being written in a positive and gentle approach.

Were the film as bad as Iger and other Disney executives want us to believe, here would still be a good reason for this book’s existence. Perhaps, though, it might have been a larger and more colorful tome.

The live action, representing about 60% of the film is not well conceived. It is terribly out of date and not well directed. Most importantly, the film is not well written. It’s somewhat confusing as to when the story takes place (pre- or post-Civil War?) What are the father’s resources, who owns the plantation where they’re living and where is the story trying to take us.

The acting by James Baskett as Uncle Remus is superb and wholly deserving of the Special Oscar he received. Child actor, Bobby Driscoll, is also fine, but many of the other performances are bland and not very noteworthy. The film is horribly dated. The Disney people sought the finest cinematographer they could get, and they did find him in Gregg Toland. He was the brilliant photographer of Citizen Kane and How Green Was My Valley. However, Song of the South was his first color film, and that was an enormous leap to make at the time. Toland had good reason to want to do the movie, but the film feels like Gone With the Wind – lite and helps to make it feel dated.

However bad the live action was, the animation was the polar opposite. The stories are told very economically with lots of excitement and life in the storytelling. All those who worked on it spoke openly about how much fun they had in doing it. Those results showed up on the screen. The characters are delightful and beautifully developed. This was certainly the spark everyone in the animation department needed as they came off years of toiling away at dry, training films for the military.

However bad the live action was, the animation was the polar opposite. The stories are told very economically with lots of excitement and life in the storytelling. All those who worked on it spoke openly about how much fun they had in doing it. Those results showed up on the screen. The characters are delightful and beautifully developed. This was certainly the spark everyone in the animation department needed as they came off years of toiling away at dry, training films for the military.

While the live action dates the material and plops it in a marginally racist context, the opposite is true of the combustible animation.

The Disney studio has hidden the DVD of this movie from the General Public. There are illegal copies of film circulating the Internet, but the quality could never be as good as a studio sanctioned copy of the movie. It’s truly unfortunate, for the sake of that great animation, that the film is inaccessible.

Korkis’ book is a very quick read and he seems to cover the story well. One would have liked a richer book with glossy images, especially of the beautifully designed Mary Blair animation.One wishes that there were lots of stills of the great Bill Peet storyboard or those great animation drawings by the Nine Masters who were truly in their prime. But we have what we have, and we’re thankful for that.

If you have any interest in this film you will have to get your hands on a copy. The last half of the book if filled with some essays about other, lesser films. Some of th essays are truly excellent and feel hidden in the back of this book. One, for example, about a commercial producing studio Walt had on the lot. Learning that Walt’s daughter, Sharon, worked as an assistant to his sister-in-law’s sister, who ran the company, would seem to be a key piece of information. But when you start to learn who Walt used to do the animation work (Tom Oreb designing for Charles Nichols directing with Phil Duncan, Amby Paliwoda, Volus Jones and Bill Justice all were among those animating. There’s even the story of Bill Peet being punished by Walt and made to work on a Peter Pan peanut butter campaign.) This is an excellent piece. As is the story behind The Sweatbox, the feature documentary that was hidden by the Disney studio about the adventures in the making of the Emperor’s New Groove. Lots to read here.

All in all, this book is an excellent bargain.

All of these illustrations were done by Mary Blair for the film.

They’re not part of Jim Korkis’ book.On Thursday I’ll repost Bill Peet’s storyboard for The Tar baby.

Articles on Animation &Books &Commentary 18 Feb 2013 04:59 am

Appreciation

The deeper you go, the deeper you go.

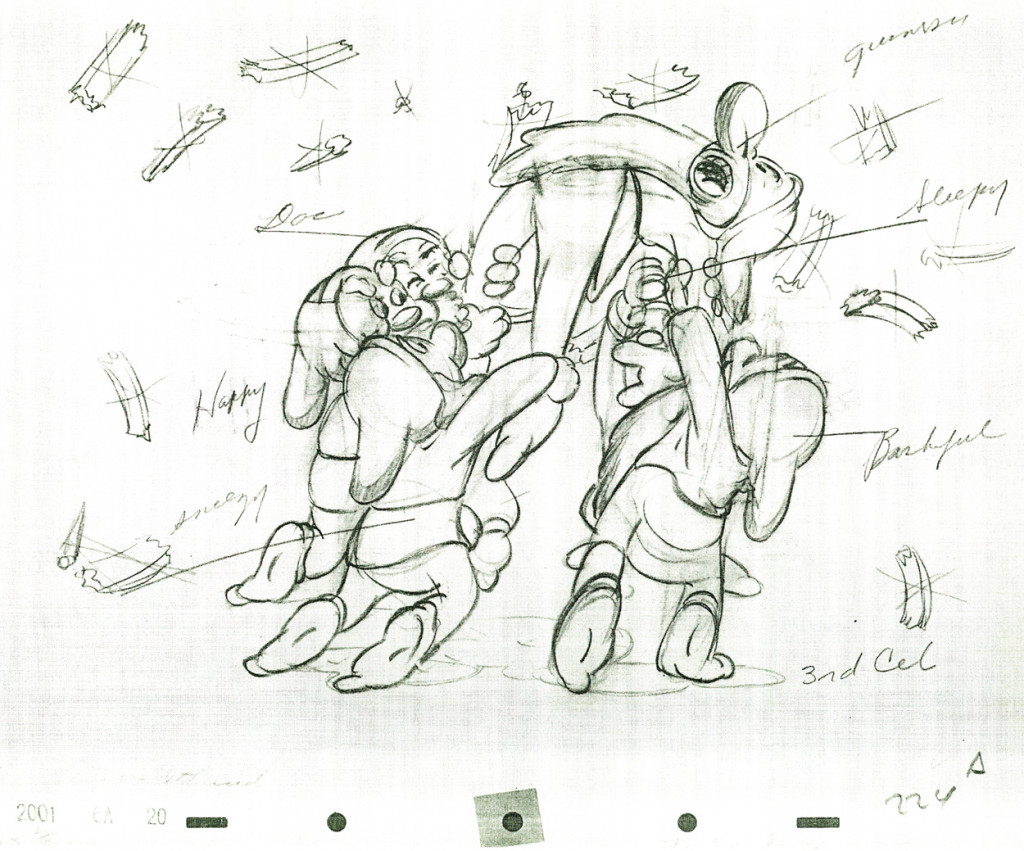

In reviewing the two J.B. Kaufman books on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, I found them impeccable in their attempt to reconstruct the making of this incredibly important movie. They followed a strict pattern of analyzing the film in a linear fashion going from scene one to the end.

In reviewing the two J.B. Kaufman books on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, I found them impeccable in their attempt to reconstruct the making of this incredibly important movie. They followed a strict pattern of analyzing the film in a linear fashion going from scene one to the end.

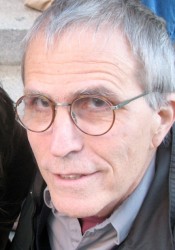

However, the analysis Kaufman offered brought me back to the bible, Mike Barrier‘s Hollywood Cartoons. Rereading his chapter on Snow White, you realize how much depth he offers in a far shorter amount of space. Of course, there are few illustrations in Barrier’s book, but what writing is there is golden. He meticulously analyzes the work of different animators using a very strict code of principles. If you can agree with him, the book he’s written opens up enormously.

However, the analysis Kaufman offered brought me back to the bible, Mike Barrier‘s Hollywood Cartoons. Rereading his chapter on Snow White, you realize how much depth he offers in a far shorter amount of space. Of course, there are few illustrations in Barrier’s book, but what writing is there is golden. He meticulously analyzes the work of different animators using a very strict code of principles. If you can agree with him, the book he’s written opens up enormously.

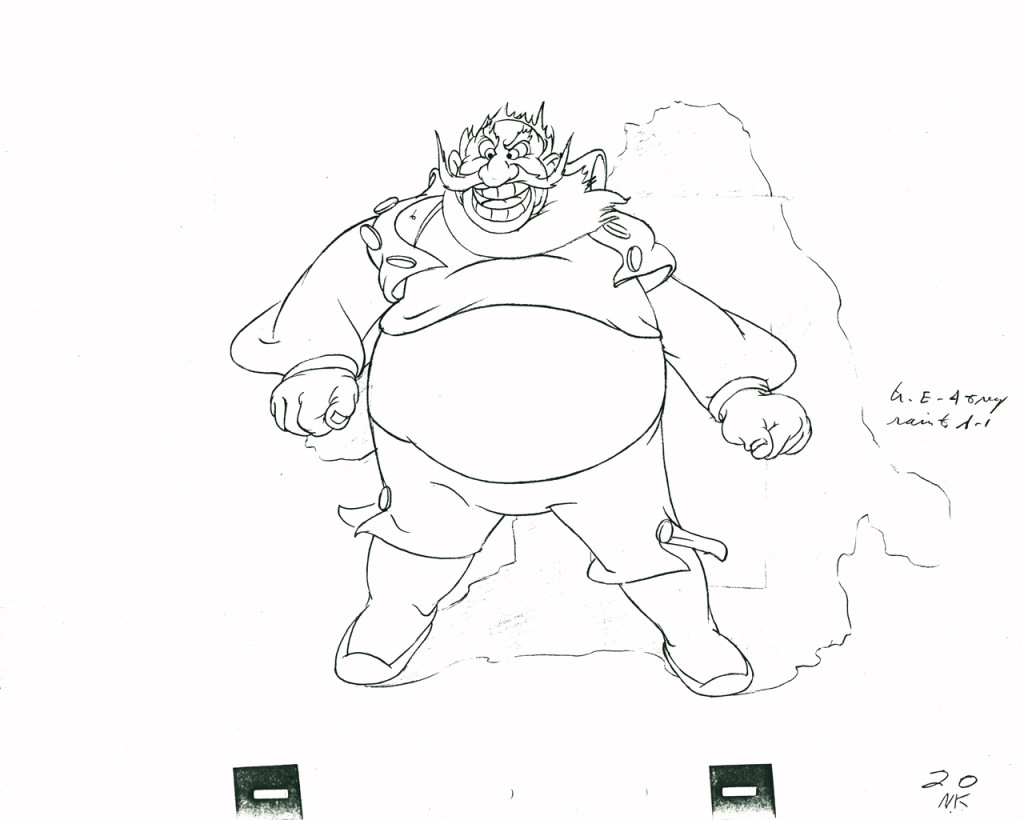

Once you get to the chapter, post-Snow White, which catalogues the making of Pinocchio, Fantasia, Bambi and Dumbo you are in the deep water. Mike pointedly criticizes some of the greatest animation ever done. His analysis of Bill Tytla’s Stromboli is ruthless. Though I am an enormous fan of this animation, I cannot say I disagree with what he has to say. Though I think differently of the animation.

Once you get to the chapter, post-Snow White, which catalogues the making of Pinocchio, Fantasia, Bambi and Dumbo you are in the deep water. Mike pointedly criticizes some of the greatest animation ever done. His analysis of Bill Tytla’s Stromboli is ruthless. Though I am an enormous fan of this animation, I cannot say I disagree with what he has to say. Though I think differently of the animation.

Here’s a long excerpt from this chapter:

- No animator suffered more in this changing environment than Tytla. His expertise is everywhere evident in his animation of Stromboli—in the sense of Stromboli’s weight and in his highly mobile face—but however plausible Stromboli is as a flesh-and-blood creature, there is in him no cartoon acting on the order of what Tytla contributed to the dwarfs. At Pinocchio’s Hollywood premiere, Frank Thomas said, W. C. Fields sat behind him, “and when Stromboli came on he muttered to whoever was with him, ‘he moves too much, moves too much.’” Fields was right-although not for the reason Thomas advanced, that Stromboli “was too big and too powerful.”

- In the bare writing of his scenes, Stromboli, more than any of the film’s other villains, deals with Pinocchio as if he were, indeed, a wooden puppet—suited to perform in a puppet show, and perhaps to feed a fire—rather than a little boy. But the chilling coldness implicit in the writing for Stromboli finds no echo in the Dutch actor Charles Judels’s voice for the character. Judels’: Stromboli speaks patronizingly to Pinocchio, as he would to a gullible child, and his threat to use Pinocchio as firewood sounds like a bully’s bluster. As Tytla strained to bring this poorly conceived character to life, he lost the balance between feeling and expression. The Stromboli who emerges in Tytla’s animation is too vehement, “moves too much”; his passion has no roots, and so he is not convincing as a menace to Pinocchio, except in the crudest physical sense. There is nothing in Stromboli of what could have made him truly terrifying: a calm dismissal of Pinocchio as, after all, no more than an object.

- To some extent, Tytla may have been overcompensating for live action that even Ham Luske acknowledged was “underacted.” But Luske defended the use of live action for Stromboli by arguing that it had kept Tytla on a leash: “If he had been sitting at his board animating, without any live action to study, he might have done too many things.”

I agree, as Barrier says, that Stromboli is a flawed character, and I agree that the movement is broad and overstated. However, I think that this was Tytlas’s only possible entrance into the material, into trying to further the characterization. No, it could not be as deep as the work he’d done on Grumpy in Snow White, but the character of Stromboli isn’t as small as that name, “Grumpy”. A lot more was offered and had to be circled to simplify as best as possible for the small amount of screen time he would have in Pinocchio. And, yes, he comes off like a blowhard with a lot of bluster. But that’s not the way Pinocchio sees him. Pinocchio is made of wood, as Stromboli reminds us, but he is also an innocent, a child learning about the world.

Barrier’s chapter, as I said, moves quickly through this material covering four of the greatest Disney films; no, four of the greatest animated features ever done. In relatively few pages you feel as though he’s gotten it all in there and has even said more in depth than almost any historian about this period of Disney animation. I’ve read this chapter at least a dozen times, and it continues to grow richer for me. I think it’s possible the greatest piece ever written about animation.

Barrier’s writing, vocabulary, choice of phrase is all charged to keep the material tight. He’s writing a large book, and he has to get a lot in.

Perhaps some day he will have one of those big picture books to write where he will have the freedom to expound on the material. I did once read such a book. Mike Barrier had been employed to write a history of the Warner Bros. studio, and I got to read the first draft of the manuscript. I had a couple of hours and sat in a chair, thumbing pages. The images that were to be in the book were on large chromes. It was all an extraordinary experience for me, and I remember it somewhat hazily, as if remembering a golden afternoon. Of course that book was cancelled when management changed hands, and the world lost a great book.

Perhaps some day he will have one of those big picture books to write where he will have the freedom to expound on the material. I did once read such a book. Mike Barrier had been employed to write a history of the Warner Bros. studio, and I got to read the first draft of the manuscript. I had a couple of hours and sat in a chair, thumbing pages. The images that were to be in the book were on large chromes. It was all an extraordinary experience for me, and I remember it somewhat hazily, as if remembering a golden afternoon. Of course that book was cancelled when management changed hands, and the world lost a great book.

Can there be any wonder that I go to the Barrier website daily, knowing full well that it’s often months between posts? I just keep looking for new material from him, and will continue my daily routine hoping for the small brightly colored package on his site. It’s almost important for there not to be frequent posts or the new ones wouldn’t always shine as well. However, two or three times a year, there is something rich there, and my search has brought the golden fish. (Yes, I’m exaggerating somewhat like Tytla did in his animation of Stromboli. But the point gets made.)

Even if there’s nothing new there, there’s plenty old. Many old Funnyworld articles or interviews done with Milt Gray. It’s a deep site full of deep writing.

Books &Commentary &Photos &repeated posts 17 Feb 2013 06:51 am

Silents Please – recap

- I’m sure I’ve mentioned before that I love silent films. I particularly am a fan of D.W.Griffith‘s work. I think I’ve read just about every book about the man’s career and biography.

- I’m sure I’ve mentioned before that I love silent films. I particularly am a fan of D.W.Griffith‘s work. I think I’ve read just about every book about the man’s career and biography.

If you’re looking for a great one, read Adventures with D.W. Griffith by Karl Brown, who was an apprentice on Birth of a Nation and Intolerance. I think often enough about Brown’s story about his daily walks with D.W. It seems that they both lived near 14th Street, and their studio was on 125th St. when they worked in NY. They’d walk together to the studio in the morning and walk home at night. The young Karl Brown would use the opportunity to learn as much as he could from the master. He tells how Griffith, at one time, pulled out a big six shooter which surprised Brown. That’s when he realized that most people carried guns. It was protection from criminals. ______Griffith filming Birth of a Nation.

I’m sure it was also protection from the patent

holders group who would beat up anyone making a film without paying for the use of a camera, whose operation was patented and owned by Thomas Edison.

Billy Bitzer, Griffith’s brilliant cameraman, reconstructed their camera so that it was different from the patent rights’ group’s cameras – therefore not in violation of the patent. This didn’t stop the constant attacks on Griffith’s sets.

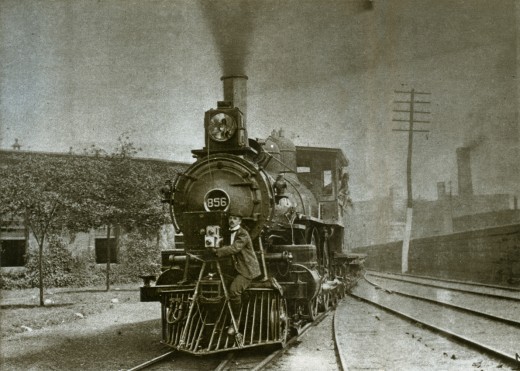

I have a book by Kevin Brownlow that I love. Photographs from the sets of silent films. Hollywood, the Pioneers is a companion book to a series he produced. The photos are outstanding. Here are a few:

Billy Bitzer on the front of a train filming the movement

for a pre-Griffith film, a Hales Tour film.

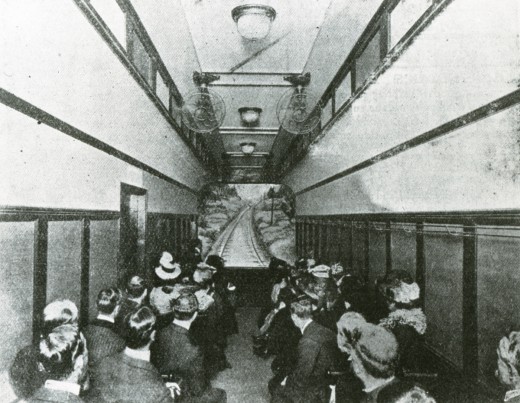

This is how the Hales tour films were screened. It’s a duplicate of a railroad car, and you ride facing the screen where you got to watch the movement, as if you were on a train. Future director, Byron Haskin, talked about spending whole days in a theater

watching these tours since they were so spellbinding.

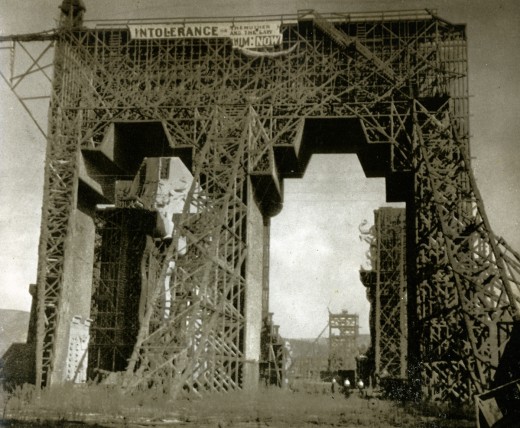

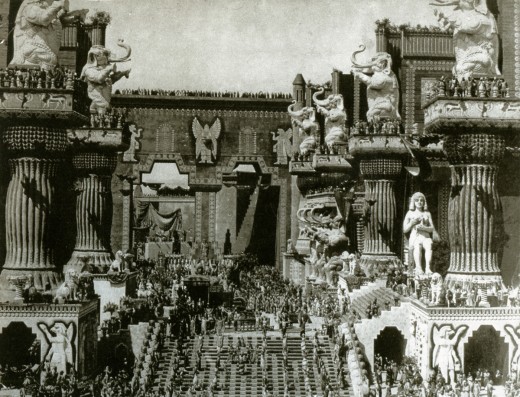

Here’s a shot of the skeleton to the set of Babylonia in the film, Intolerance.

This film was shot in California. Film makers ran to the west coast

as much to escape the patent holders as to find all sun all the time.

This is what the final set looked like for the film. (Those are

real people and elephants inhabiting the set, not computerized creations.)

This is closer shot of one of the elephants that lined the walls. The care that was put into these films was amazing. Griffith loved recreating famous paintings and etchings that illustrated the stories he was filming. Quite often, the intertitle would tell you that you were watching such a recreation and show you the painting.

This is closer shot of one of the elephants that lined the walls. The care that was put into these films was amazing. Griffith loved recreating famous paintings and etchings that illustrated the stories he was filming. Quite often, the intertitle would tell you that you were watching such a recreation and show you the painting.

After the film was completed, the set remained standing for many years. If Roger Corman had been around at the time, there would have been another dozen films featuring it.

There’s also a wonderful Italian film by the Taviani brothers called, Good Morning, Babylon. It’s about two architect brothers who emigrate to the US and get work helping to build the set. It’s worth hunting down for a look.

The Griffith film led to bigger and bigger sets.

This is Ernst Lubitsch’s German film, Loves of a Pharoah.

Douglas Fairbanks got even larger with his set for The Thief of Baghdad.

Years later, after a number of films had failed for him, Griffith tried to make one more special film. He bought some land in Mamaroneck, NY and built his own studio. There he had constructed Paris. This would be the set for Orphans of the Storm.

Years later, after a number of films had failed for him, Griffith tried to make one more special film. He bought some land in Mamaroneck, NY and built his own studio. There he had constructed Paris. This would be the set for Orphans of the Storm.

It was a film that featured the sisters, Dorothy and Lillian Gish. The girls are separated in the period melodrama. here, Dorothy, playing the blind sister, is searching the streets for her sister.

She isn’t very successful and sinks lower and lower into the depths of revolutionary France. Needless to say, there’s eventually a reu-nion.

Lillian took a very big part in the making of these films. During Intolerance she actually was an uncredited editor. Since she had a small role in the film, she would spend the days assembling footage to view with D.W. in the evenings and would rework the film to Griffith’s instructions on the next day.

There was no script when they started this film. Griffith wrote it all and kept it in his head as he shot the film. This was quite a feat since it’s four separate stories that are interwoven. (The first time this was done on film.)

Anita Loos was employed, early in her career, after the fact to help write the intertitles and offer suggested changes to the footage.

In 1917, during WW I, Griffith actually went to the French front to film his movie,

Hearts of the World. The film was financed with British money as

early propaganda. The footage shot in France wasn’t all he’d hoped for,

so some of it was recreated back in the US when he returned.

Bill Peckmann &Books &Comic Art &Disney 07 Feb 2013 04:56 am

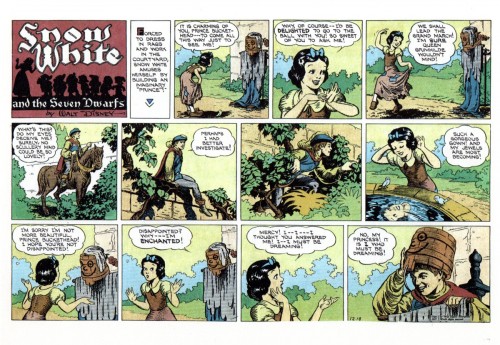

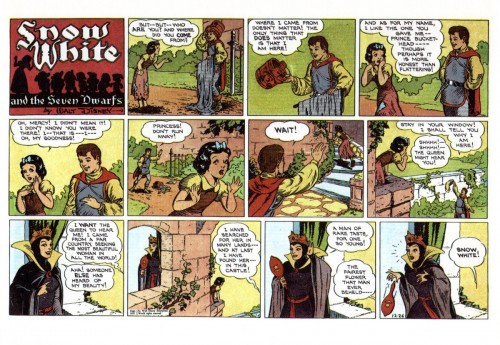

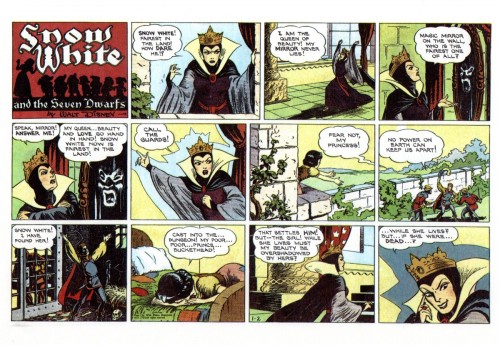

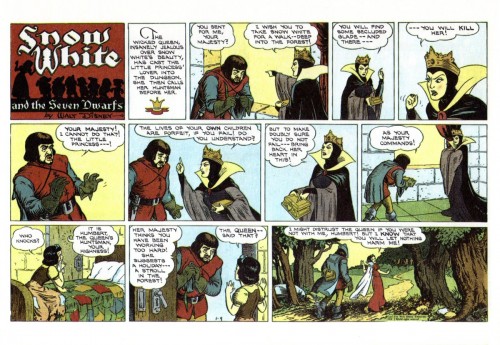

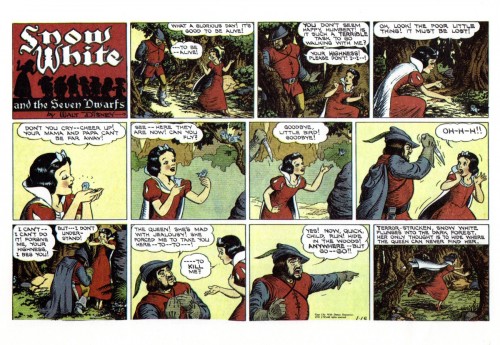

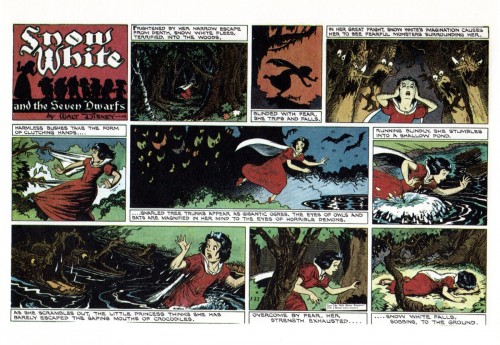

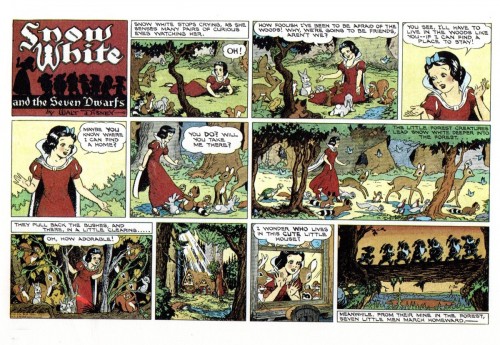

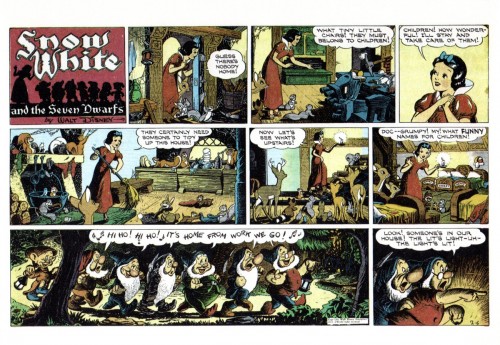

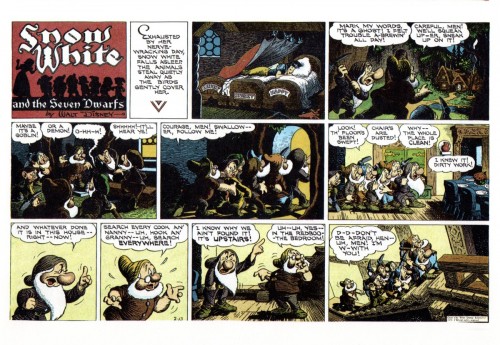

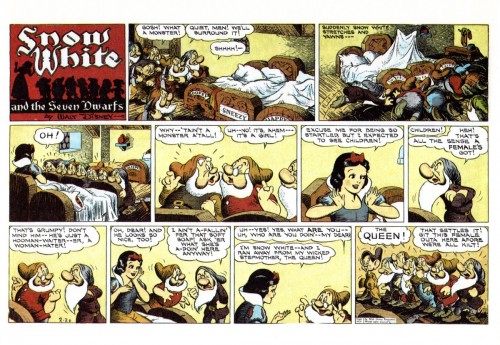

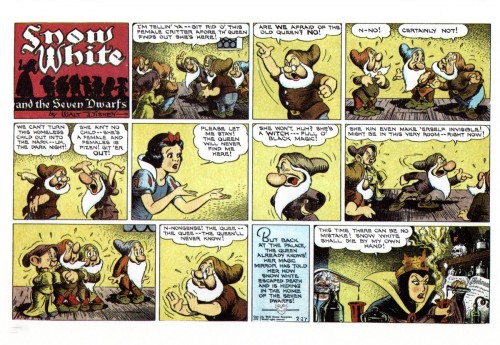

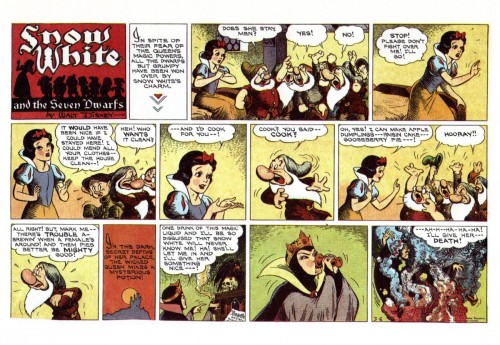

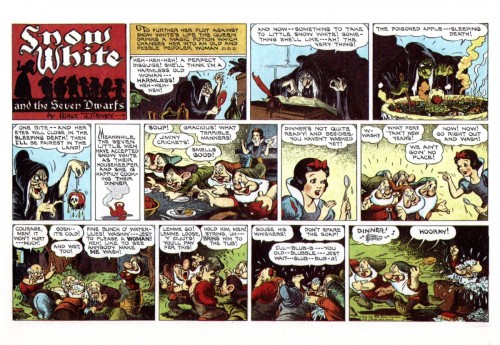

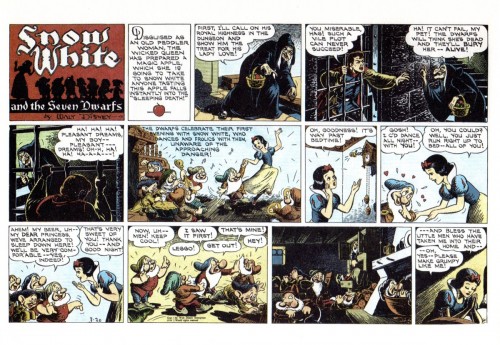

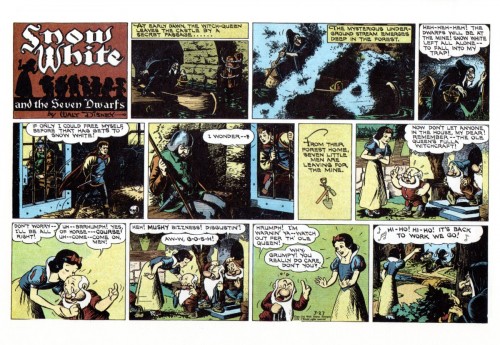

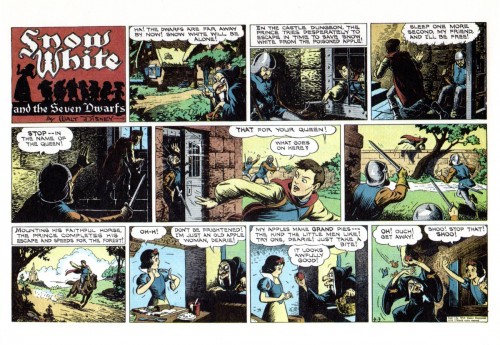

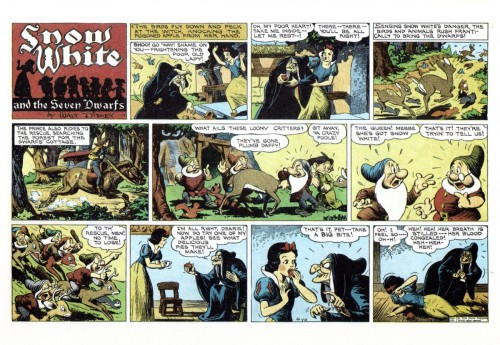

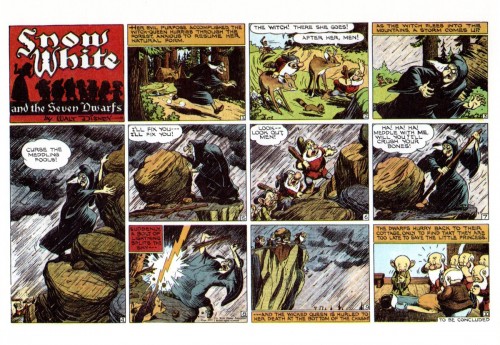

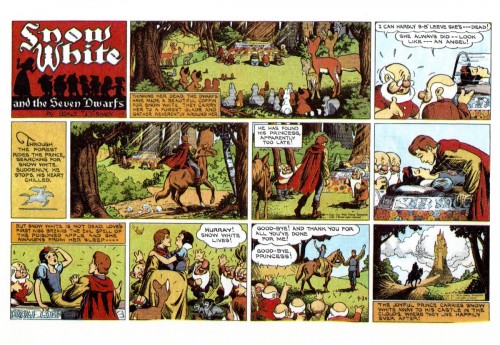

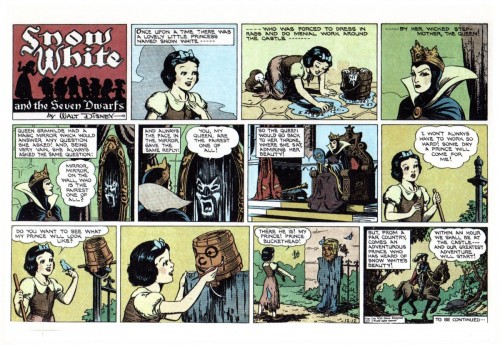

Snow White – the original strip

Well involved with the two J.B. Kaufman books on Snow White, and about to re-read Mike Barrier‘s writing on the making of the feature, per his book, Hollywood Cartoons, you can be sure that a lot of Snow White material is going to comve your way via this blog.

Bill Peckmann offered to send the initial strip done to coincide with the release of the feature, so thank you, Mr. Peckmann, I couldn’t be happier than to offer this.

Disney had, since 1932, a Silly Symphony comic strip that ran weekly. With the release of Snow White, the strip’s regular writers were replaced with writer, Merrill De Maris, pencils artist, Hank Porter, and the inker, Bob Grant. The strip continued for a full 20 weeks, beginning on December 12, 1937.

There are noticeable differences between the story in the strip and the released film. The movie’s story, from the start, had a sequence called “Prince Buckethead” which lasted in the original storyline until the last months in making the film. Then the sequence found itself dropped from the film, but, oddly, reappears in this comic strip version. It’s a game the Prince plays was supposed to play with Snow White at the beginning of the movie. The Prince also is imprisoned in the original story in the caverns of the castle; the same is true here. Other things like the huntsman having the name, “Humbert,” return to the story. I’m curious as to who made these decisions to keep the noticeable differences. Many versions of the stirp appeared over the years and in many languages. You can check them out here.

Without wasting more time, here’s the original strip.

1

1

Thanks, again, to Bill Peckmann for putting this all together.

Animation &Books &Commentary 26 Jan 2013 08:53 am

George and Friends w/Books

- I admit it; I am getting older, and I have completely different thoughts on what animation is than most people half my age. I have no intention of apologizing for that, because that’s what I believe and cherish and enjoy.

This past week there was a program of animated work by George Griffin. He ran the show in achronological order starting with the most recent material and ending with the oldest. That show was animation. Everything in every frame (though there are no more frames) or bit of particle of George’s work and being is animation. He not only loves animation, but he is animation. It was a wonderful show to attend.

This past week there was a program of animated work by George Griffin. He ran the show in achronological order starting with the most recent material and ending with the oldest. That show was animation. Everything in every frame (though there are no more frames) or bit of particle of George’s work and being is animation. He not only loves animation, but he is animation. It was a wonderful show to attend.

George enjoys showing the hardware and the techniques, the guts of the animated creature and the sprockets of the projector, if in fact there is a projector. His first “films” were bits and pieces live and animated. His very first piece was a filmic trick that Méliès and Blackton probably did in their first movies. George took the crumpled piece of paper in his hands and unfolded it to a crisp, new sheet of clean paper – he played the film backwards, of course, and with that, he started the show.

All of the films shown utilized such tricks and bits, punching and stabbing with animated games, study and punctuation. Even taking his film, Flying Fur, in which he originally took a great Scott Bradley score for an MGM cartoon and put his own visual accompaniment. Not leaving well enough alone he remade his own film with Flying Fur Fragments. This has George, himself, go into his basement and rummage through odds and ends and artwork from the original short and we see these pieces come to life in his hand with a reconstructed, rehashed version of the great Bradley score. Skips and hops, walks and chases are pulled from the original to accent the accents in the music . It’s just pure joy in early 21st Century seeing what feels like be bop animation to a wildly modern musical score written in 1944.

All of the films shown utilized such tricks and bits, punching and stabbing with animated games, study and punctuation. Even taking his film, Flying Fur, in which he originally took a great Scott Bradley score for an MGM cartoon and put his own visual accompaniment. Not leaving well enough alone he remade his own film with Flying Fur Fragments. This has George, himself, go into his basement and rummage through odds and ends and artwork from the original short and we see these pieces come to life in his hand with a reconstructed, rehashed version of the great Bradley score. Skips and hops, walks and chases are pulled from the original to accent the accents in the music . It’s just pure joy in early 21st Century seeing what feels like be bop animation to a wildly modern musical score written in 1944.

Speaking of be bop, George did just that when he animated a short homage to Charlie Parker in the film, Ko Ko. Taking a piece of music performed by ther great Parker in 1945, George visualizes every note and muscle of that great piece of music. The animator has found the heart of the music and given us all the fun in it with his very singular view of that score. This film’s a treat that can be watched over and over.

Speaking of be bop, George did just that when he animated a short homage to Charlie Parker in the film, Ko Ko. Taking a piece of music performed by ther great Parker in 1945, George visualizes every note and muscle of that great piece of music. The animator has found the heart of the music and given us all the fun in it with his very singular view of that score. This film’s a treat that can be watched over and over.

George shared a commercial he did in the style of Keith Haring, and though the animator apologized for the “bad animation” in the film, I didn’t see a bad bit in it. As a matter of fact I’ve seen about a half dozen Harings animated, and I can’t think of a better match for that graffiti artist than George and his own style.

The one film that was very representational was a film he did with his daughter, Nora. It’s a very sweet movie called A Little Routine. It’s a wonderful little piece that illustrates the daily routine with the father putting the daughter to bed. George uses lots of imagery in a semi-abstract way as something so simple as escorting his daughter from the bathroom to the bedroom involves trekking over countryside terrain bringing the little girl to the safe part of the woods where she will have no worries or fears. When she wakes in the night desperate for a glass of water, we hear daad shouting miles away that he’ll bring the water and we see him making that routine trip to the bedroom to protect his little girl. It all happens in a flash, of course, something that can be done so easily in animation. The film seemed to touch many in the audience that wanted the more representational world for the break of it, and they didn’t seem in any way disappointed when we were back to sterner stuff.

The one film that was very representational was a film he did with his daughter, Nora. It’s a very sweet movie called A Little Routine. It’s a wonderful little piece that illustrates the daily routine with the father putting the daughter to bed. George uses lots of imagery in a semi-abstract way as something so simple as escorting his daughter from the bathroom to the bedroom involves trekking over countryside terrain bringing the little girl to the safe part of the woods where she will have no worries or fears. When she wakes in the night desperate for a glass of water, we hear daad shouting miles away that he’ll bring the water and we see him making that routine trip to the bedroom to protect his little girl. It all happens in a flash, of course, something that can be done so easily in animation. The film seemed to touch many in the audience that wanted the more representational world for the break of it, and they didn’t seem in any way disappointed when we were back to sterner stuff.

George Griffin understands animation; it’s in his lifeblood and he offers it to us an any way he can: flipbooks, mutoscope, dgital refilming of 16mm, movie files or purly digital sections. He feels that there is no need for the apparatus as long as we want to get out the animated bits.

The evening was an inspiration. Thank you, George.

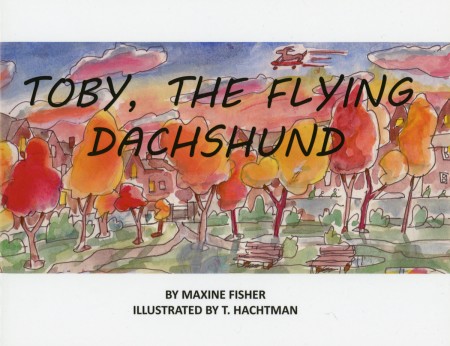

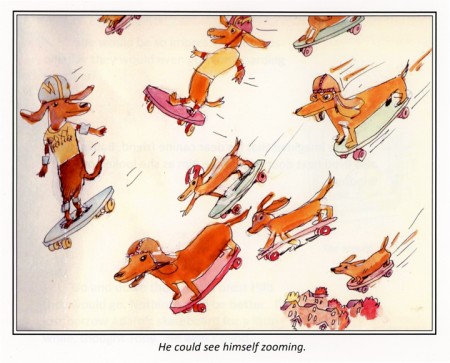

- Some friends and past employee/friends have been busy writing and illustrating children’s books. I thought I’d show off three of them and write a few words about them. (If you can’t promote your friends’ work, who can you promote?)

Three long-time very close friends have joined together to do a children’s book. Maxine Fisher has written most of my scripts (including POE) and she and Tom Hachtman put together a book about a dachshund. Max loves her pet, of course, and has now immortalized her in this book. Tom did the illustrations and Max’s brother, Steve (who does all those brilliant Sunday photos for me) put the book together and they self published on Lulu. That means you can buy it directly from Lulu, and I think it’s worth it. They’re still looking into Amazon, so maybe soon.

But I thought I’d post a few of the pics from the book and let you see how great it turned out. Tom wrote that he was finishing the last illustration as his yard (and eentually house) was being flooded by Hurricane Sandy.

Go to Lulu to find out more about the book.

___________________________

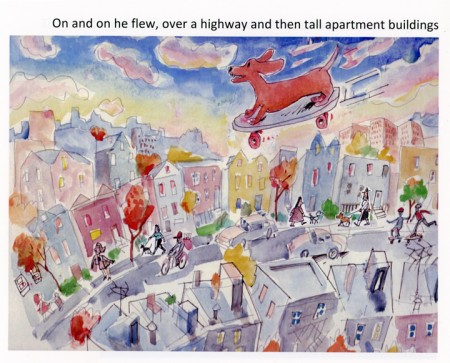

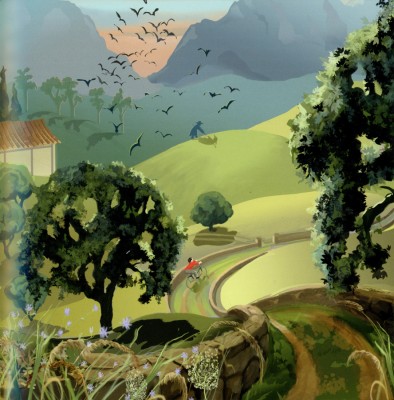

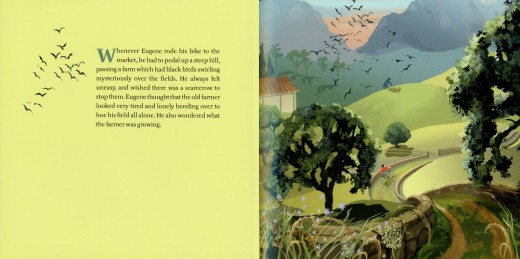

- Laura Bryson worked with me for years doing backgrounds for a number of the half hour shows (like The Red Shoes and The Marzipan Pig). Now she’s out freelancing and painting and has recently turned out her second children’s book which she co-authored and illustrated.

The book uses the Chinese Zodiac within the theme of the book offering Laura plenty of opportunity to paint nature and animals. The color palette is quite controlled as is the quiet story. The book can be found on Bestboypublishing.com.

Here are a few other samples from the book:

1

1

Illustrations on every other page give plenty of opportunity

of using flat colors to set up the next page.

3

3

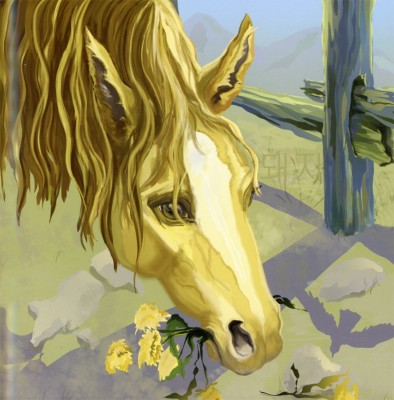

And, of course, Laura who loves her horses

makes sure to include one to illustrate.

___________________________

- Finally, we have Stephen Maquignon. Steve’s illustrated many books since he left animation, and each one gets more sophisticated than the last. I asked him to send me some art from a couple of books he wanted to highlight, and he did. I’ve chosen the following pieces from both books.

1

1

3

3

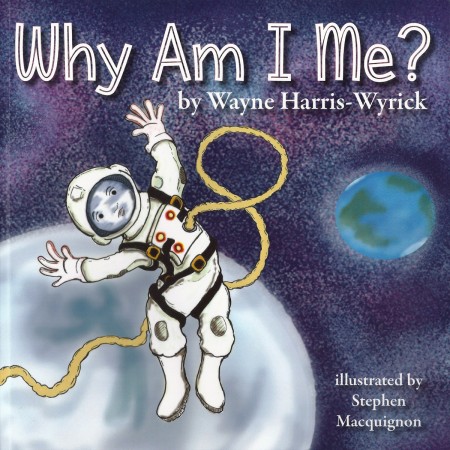

This second book, Why Am I Me? seems very clever. Steve wrote the following about the book:

When I read this one I could not see one main character in it, a big question, and

I thought it deserved many voices so each time the question why am i me pops up

I put in a different kid in a different situation.

Kind like the ride at Disney world “It’s a small world after all”

Stephen has a number of sites on which you can see more of his artwork and order copies of his books if you’d like to:

This is a link to his bio page on amazon it shows all the books he illustrated.

likewise Barnes & Noble

This is his primary personal site as a Children’s Book Illustrator