Category ArchiveBooks

Articles on Animation &Books &Commentary &Independent Animation 20 Jul 2010 07:50 am

Women Animators

- Back in the enlightened Eighties, Independent animation actually took note of gender in the making of animated films. In The Art of the Animated Image, An Anthology edited by Charles Solormon included an article about Women Animators in the medium. The article by Lauren Rabinovitz was part of a series published in conjunction with the Walter Lantz Conferences on Animation held June 12th thru 14th, 1987 at the American Film Institute in LA.

I reprint the article here, and I consider that, to my knowledge, it’s nice to know that all but one of these women mentioned are still making Independent films. I wonder if the record is as strong for the “Independent” male animators of the same period.

and

Women’s Experiences

BY LAUREN RABINOVITZ

Histories of American animation have most often located the form within the confines of the Hollywood cinema and television system. Over the seventy-five years or so of its existence, that system has seldom proven hospitable to women filmmakers, or animators, whether they were working in film or, later, in television.

Outside Hollywood, the medium of animation has flourished in the work-a-day world of education, industrial and advertising films, and in those arenas women animators have found opportunities not available in Hollywood (especially over the past twenty years). Of even greater significance, the growth of avant-garde film after World War II nurtured female, as well as male, animators, filmmakers dedicated to individual artistic expression and to the creation of new film syntaxes within an alternative economic support system.

As independent cinema became increasingly tied to college and museum institutional frameworks in the late 1960s, so too did the individual filmmakers. In that period and thereafter, they typically became identified with academic training and teaching positions, the aesthetic vocabularies of vanguard art movements, and the apparatus of an American avant-garde cinema. In the 1970s and 1980s, rising from those antecedents, feminist filmmakers and animators have participated in independent cinema networks.

However much independent cinema may be viewed as a “marginal” practice within the Hollywood hegemony, women filmmakers—and animation as a cinematic form—lie at the outskirts of those heterogeneous cinematic margins. As neither women filmmakers nor animators have extensive showcases, distribution outlets, and production monies available to them, their short works are known largely through a variety of exhibition practices: film festivals; distributors’ animation packages (often collected for and exhibited at schools and film societies); cable TV “fillers”; and individual (and often visiting) artist screenings at museums, colleges and media centers.

Within this somewhat limited and restricted production, distribution and exhibition network, women animators have created a broad spectrum of work, utilizing a range of animation techniques, styles, and subjects. Line animation, cut-outs, xerography, photos, computer-generated imagery, sand-on-glass, have all been used by woman animators. Some have chosen to explore formal and spatial relationships; others delve into the “serious” art of highly abstracted, non-representational animation. Some have relayed children’s stories and folktales, personal experiences and feelings; others have created humorous narratives and political satires. Many have chosen to construct animated tales that comment on the artistic process itself. There is no “women’s animation” any more than there is one unique form of women’s film or video.

Nonetheless, just as male filmmakers have frequently exposed intimate, often sexual experiences from a subjective point-of-view, women animators tend to explore women’s experiences from an equally subjective perspective. Such subject matter takes on a dual political dimension—in the increased visibility and expression of gender identities and experiences, and in the recognition of the systematic repression of women’s subjective experiences within the Hollywood cinema. A significant number of contemporary women animators rely on cartoon animation— figuration in short narratives—as a means of recasting their relationship to the ideology of representational cartoons.

There is a long list of recent films by women animators that address women’s experiences in this fashion. They run the gamut, from Tanya Weinberger‘s tiny naked woman who carouses on and then arouses a sleeping giant in Gulliver Comes to Lilliput (1983) to Suzan Pitt‘s Asparagus (1978), an elaborate eel-animated psychodrama that intertwines a woman artist’s creative process with metaphors of sexual activity.

Christine Panushka‘s The Sum of Them (1983), line portraits set against a familiar collage of sounds, depicts many women as an absorbing poem of humanity. In Another Great Day (1980), Jo Bonney and Rugh Peyser dramatize the important inter-relationships among popular cultural forms, fantasies, and women’s labor through a housewife who moves freely between the cartoonesque world of her chaotic household and the photographic world of television soap opera and romance photo-novels. Women have also collaborated to celebrate collectively their experiences as’ women who are not always “solitary” animators. Lisze Bechtold, Lesley Keen, and Candy Kugel, My Film, My Film, My Film (1983); Caroline Leaf and Veronica Soul, Interview (1979).

Some artists portray an autobiographical female subject notable for her physical metamorphoses, which approaches self-induced schizophrenia. In turn, this state of fluid change can often provide a positive catharsis. For example, Karen Aqua‘s Vis-a-Vis (1983) turns the artist/character into two connected halves of one person—the animator at her storyboard and the woman gazing out the window. When the halves split, the artist animates kaleidoscopic images while the woman passes through richly colored sea and mountains. When the woman returns to the artist, she empties radiant color into the drawings.

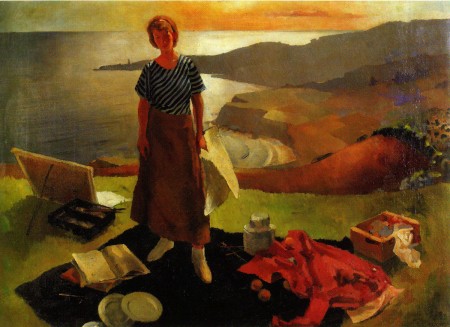

Kathy Rose’s Pencil Booklings (1978)

Kathy Rose also plays with the magical transformations of an animator character. Mirror People (1974) and The Doodlers (1975) both rely upon the protagonist’s constantly evolving physical shapes in an eerie, surrealistic world. In Pencil Booklings (1978), the artist/character (who resembles Rose) is represented more naturalistically through rotoscoping. Within the narrative she is pulled into the world of her imaginative creation and eventually back out of it, her identity assured by her exploration of the creative process itself.

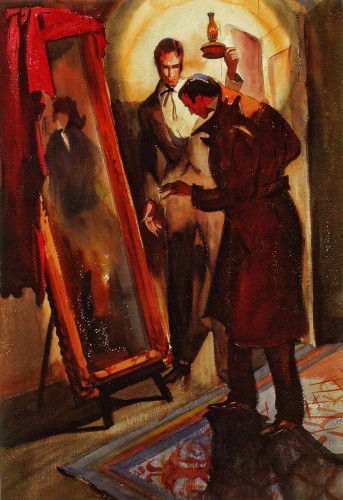

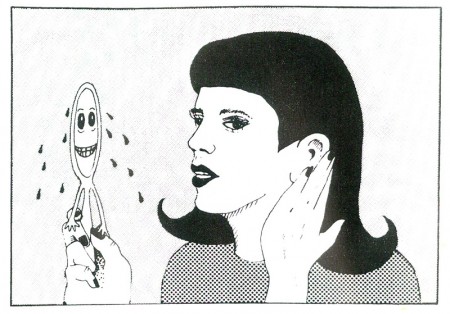

Joanna Priestley‘s Voices (1985:) also relies upon the artist’s physical presence as well as her v ice to comment on her self-image. As a likeness of the filmmaker addresses an anthropomorphic (and smart-alecky) mirror, she describes first her bodily-related fears of aging, gaining weight, and wrinkles. As she succumbs to her preoccupation with fear itself, she gives vent to increasingly cataclysmic horrors that are visually portrayed— things that go bump in the night, monsters of the id, nuclear holocaust. The background prattle provides a counterpoint to the character’s self-absorbed fears creating a tongue-in-cheek commentary that suggests women’s fears about themselves are a culturally induced neurotic obsessiveness.

Joanna Priestly’s Voices (1985)

It is important to note that these artists depart from the traditional Hollywood use of sound, the acoustical enhancement of nature. Although the cartoon world may always be seen as inherently fantastic, the animation studio’s use of sound helped reinforce the notion of a spatial and physical world. These animators employ layers of sound effects and music to destabilize the spectator and to stress the fantastic itself.

Emily Hubley, the daughter of animators John and Faith Hubley, carries the metamo-phosing, autobiographic subject to new intensities. In Delivery Man (1982), she presents a simply drawn, ever-changing abstract self in an equally volatile, abstracted world. Less the object of whimsical artistic introspection than the subject of her fearful dreams relived, the constant visual metamorphosis supports a remembered vision of personal traumas. The woman’s personal narrative of five key dreams involving her birth, her mother’s surgery, and her father’s death during surgery visualize the crisis of familial relationships, development and sexual identity that comprise the subjects of many patients’ transactional analysis.

Kathy Rose has extended the woman animator’s autobiographic involvement to a redefinition of the medium itself. Her Primitive Movers (1982) is a 30-minute piece that combines animation and Rose’s dance performance in front of the moving images. The animation is a constantly moving, colorful backdrop of lifesized dancers who evoke series of art styles—from Egyptian to Cubist to Art Deco. Their relentlessly rhythmic, angular movements provide not so much a chorus line for Rose’s sharply expressive movements but a fluid commentary on changing spatial relations, perspective, and Rose’s intertwining of 2 and 3 dimensions, as well as her bodily interaction with them.

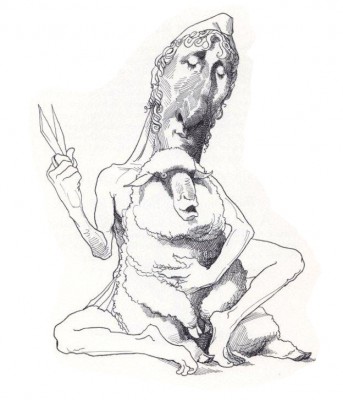

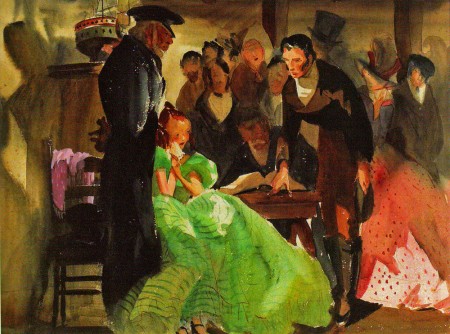

In this regard, several women animators connect their work to the history of art in ways that allow them to reconstitute woman’s place—no longer the object of male desire, but as the controlling subject. Maureen Selwood‘s Odalisque (1981) is, perhaps, the best example. In a humorous inversion of the history of western painting, Selwood portrays her odalisque as the subject who imagines and controls the flow of images. This female is no longer the prisoner of other artists.

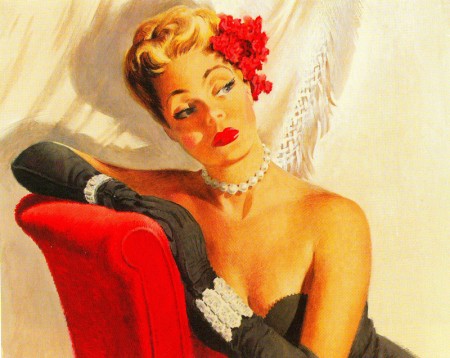

Maureen Selwood’s Odalisque (1981)

Selwood calls attention to a more naturalistic figuration as the basis for a realism regarding women in Western art. By juxtaposing two styles in a jarring fashion, she poises fluid, graceful motion associated with the feminine against the disintegration and evaporation of form associated with the cartoon world. Made with the aid of romance and adventure—as a cafe artist and an opera singer—in these dreams, she deflates as male fantasies the romantic conventions usually associated with these constructs. In each sequence, she escapes the conventional confines of the fantasy that would relegate Woman to passivity or death and flows back to her living room, her visually nurturant world.

Whether there is an inherently feminine language in these works as well as in women’s writing, visual arts, and other expressive arts has been a topic of much feminist discussion in the 1970s and 1980s. Some critics maintain that even acknowledging the existence of feminine language does not insure that such “inscriptions of women’s voices” will be necessarily heard by all audiences. Female filmmakers frequently rely upon existing codes and conventions no matter how much they are filtered through their own vocabulary. In addition, their audiences may choose to interpret the films within the confines of already established canons, an act sometimes amplified by the films’ marketing and critical reviews.

What is at stake here is not the discovery of a feminine or feminist aesthetic running through women’s animated films, but the ways in which contemporary animators collectively construct feminist experience. They rely upon devices usually associated with expressive animation—physical metamorphosis, strongly-defined character personalities, and dream-like fantasy logic. But they represent these processes by defining women as their subjects, presenting specifically female sexual and non-sexual fantasies, and imagining self-identity and fears through one’s physical changes and fluidity as well as through controlling the environment outside oneself.

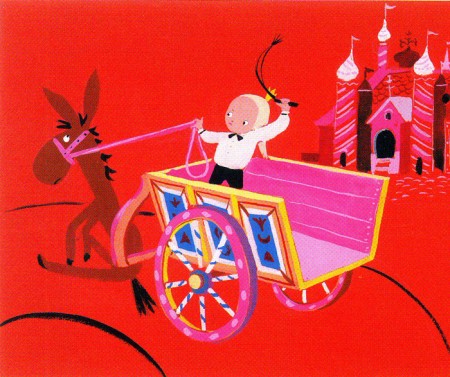

Books &Disney &Illustration &Layout & Design &Mary Blair 19 Jul 2010 07:58 am

Mary Blair – 2

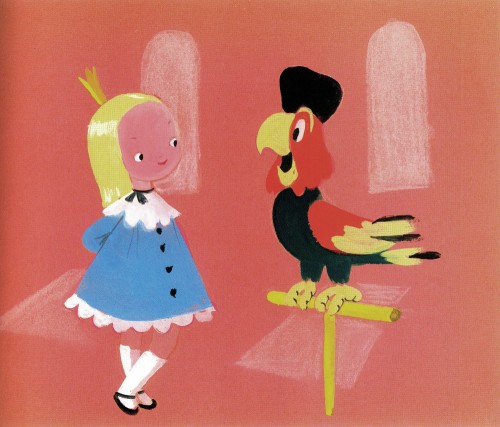

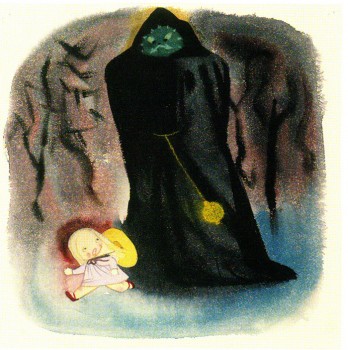

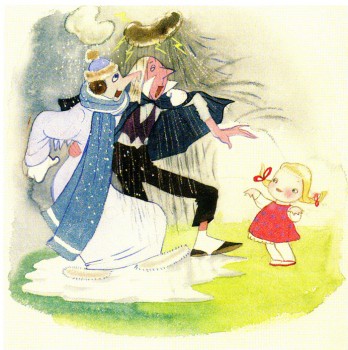

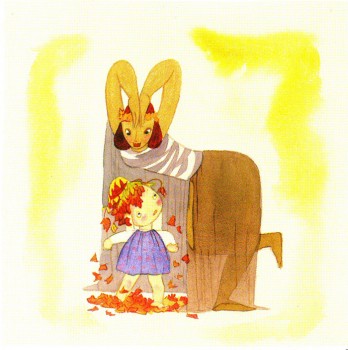

- I’d like to continue showing some of the Mary Blair work pictured in the Japanese book, The Colors of Mary Blair.

The work is sensational, of course, but they aren’t very well identified (in English). Hence I’ve chosen images almost at random without really knowing what projects they’re designed to illustrate. When I do have information, I’m passing it along. I suspect others of you may be able to identify it better that I. (I certainly don’t consider myself an authority on Mary Blair.) If so, please feel free to leave comments.

Mary Blair at Disney.

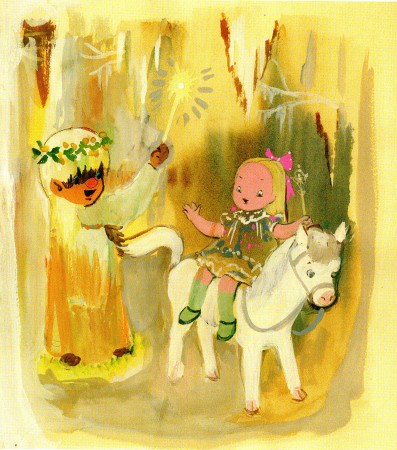

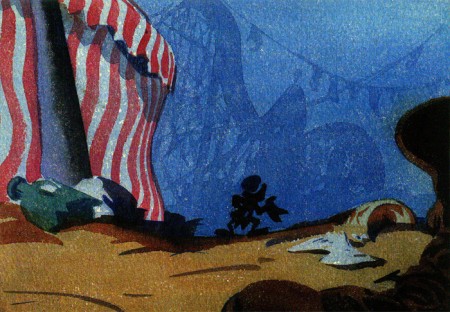

These first 5 images are from Penelope, a feature about a

time-travelling girl that was never produced.

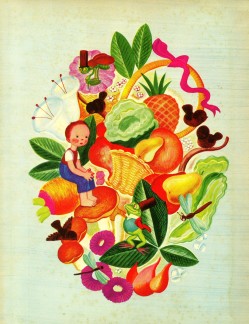

The following group come from various sources.

Some are from Penelope, although others look like they were

done on the South American trip, with the bold colors.

The following group of six are labelled: “Upsidedownia.”

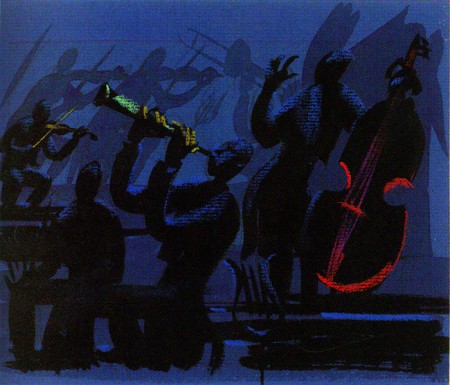

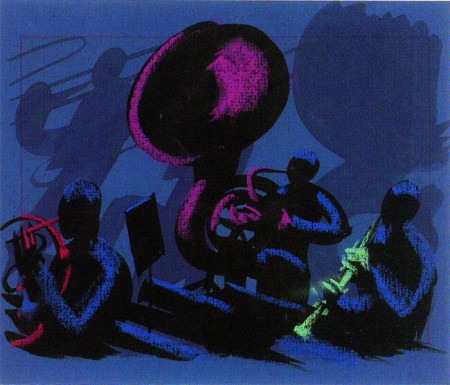

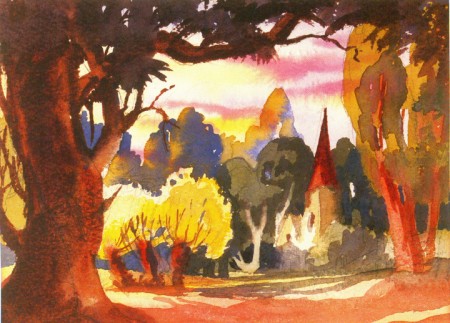

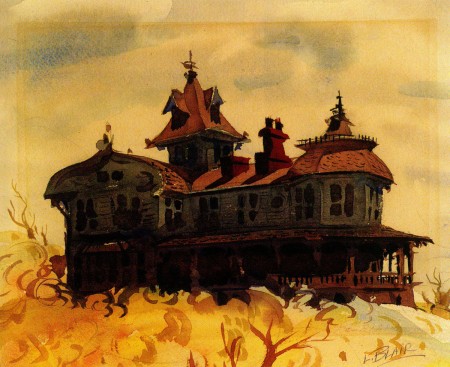

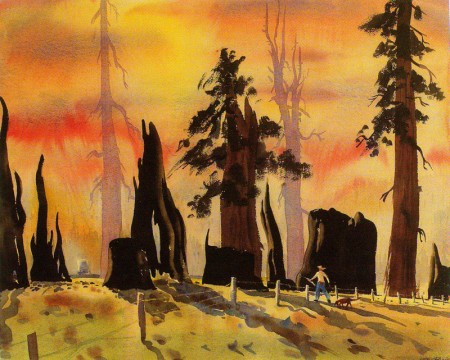

Here are some watercolors Lee Blair did for Fantasia:

And a couple for what looks like Pinocchio.

Bill Peckmann &Books &Illustration 17 Jul 2010 07:17 am

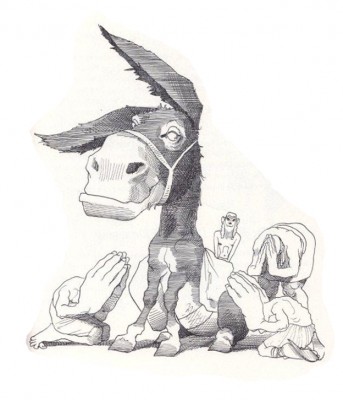

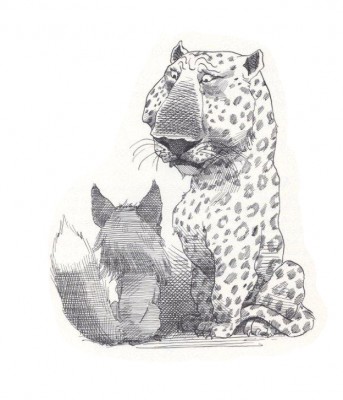

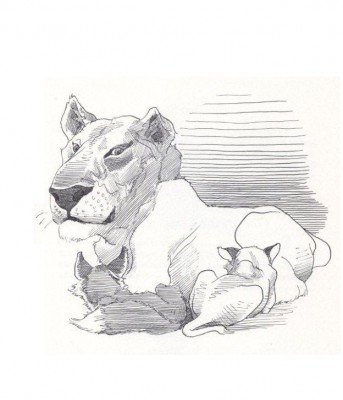

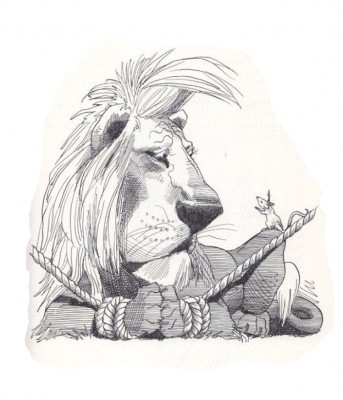

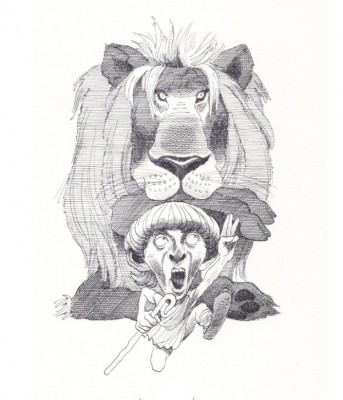

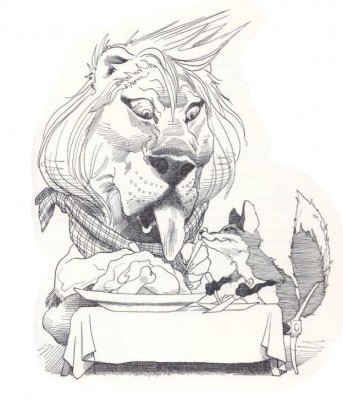

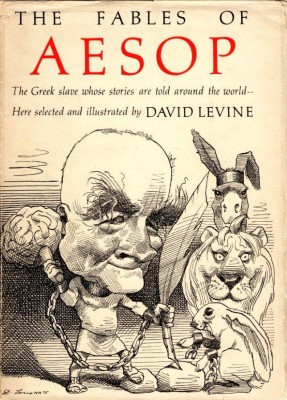

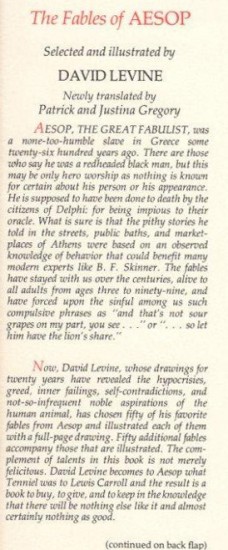

David Levine Lions

- Bill Peckmann sent me a parcel of lions and Aesop’s Fables from David Levine. These dawings are so brilliant that it’s impossible not to share them today. Enjoy.

Many thanks to Bill.

The cover ant the (enlarged) frontispiece from the book.

2

2

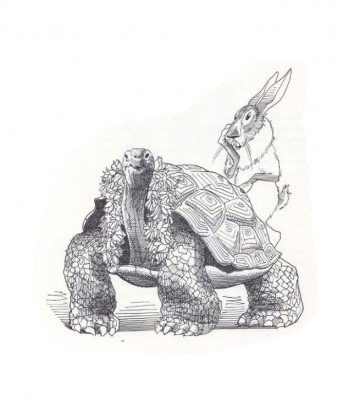

They don’t get any more gorgeous than this turtle and rabbit.

Books &Disney &Illustration &Layout & Design &Mary Blair 12 Jul 2010 07:03 am

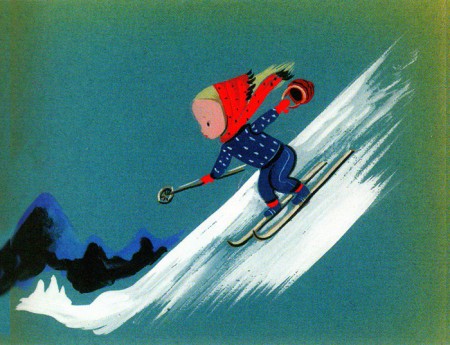

Mary Blair – 1

(Click any image to enlarge.)

- I received a magnificent gift, recently, from John Canemaker. It’s a book that was published in Japan that intensely focusses on the work of Mary Blair, the brilliant artist who

designed and stylized many Disney’s golden films.

designed and stylized many Disney’s golden films.

The book is chock-a-block with images, and even though most of the writing is in Japanese, the book is a glorious item to read through – just for the pictures. Fortunately, there is identification in English under all of the images. John Canemaker also has a wonderfully written Foreward in the book.

I’m going to make a couple of posts selecting some images that I found exciting and relevant to Ms. Blair’s career. Included, of course, will be some paintings and designs by her husband, Lee Blair, and her brother-in-law, Preston Blair.

I’m sure a lot of the paintings were chosen to act as a comparison to some of the animated segments done by the trio. Take, for example, “Woman with Red Flowers in Hair” by Preston Blair.

This post will attend to the pre-Disney paintings of all three artists.

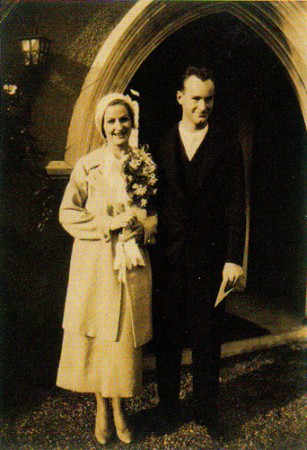

Wedding Photo – March 3, 1934

Mary and Lee Blair

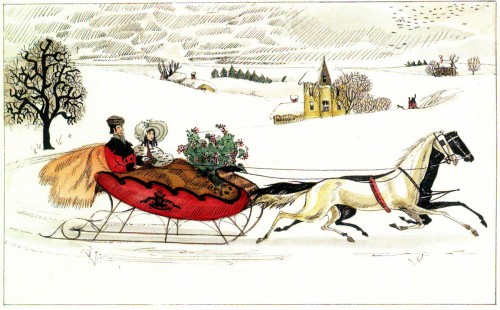

Mary Blair – Couple in Snow Sled

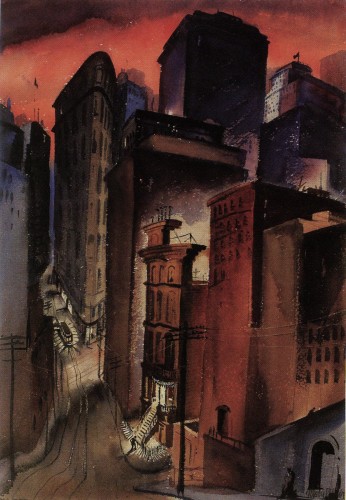

Mary Blair – San Francisco Nights

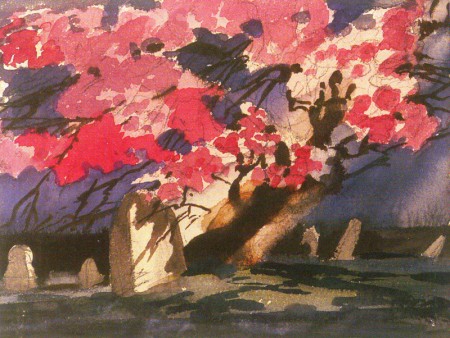

Mary Blair – Landscape of Trees

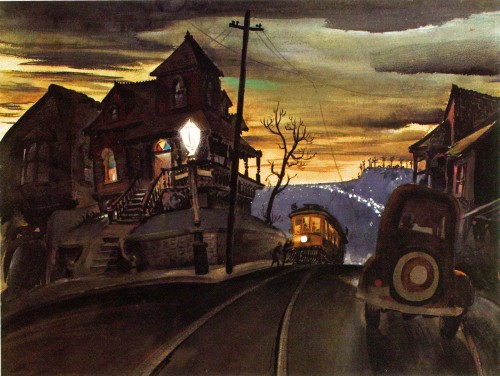

Preston Blair – Night Street Scene with Cable Car

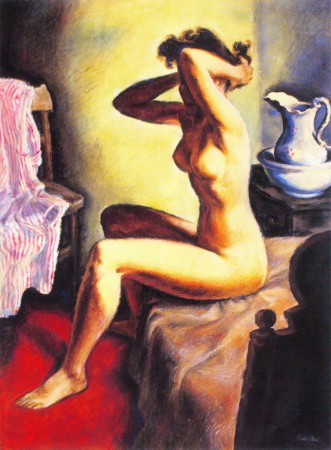

Preston Blair – Female Nude Preening

May I also remind you that John Canemaker has a wonderful book available in the US. The Art and Flair of Mary Blair is still for sale on Amazon.

Bill Peckmann &Books &Illustration 02 Jul 2010 07:48 am

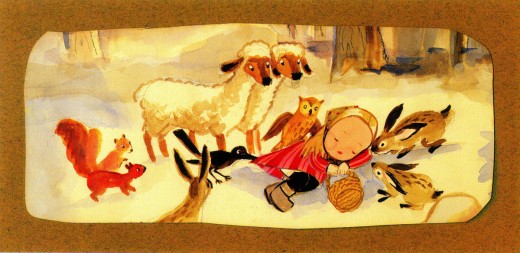

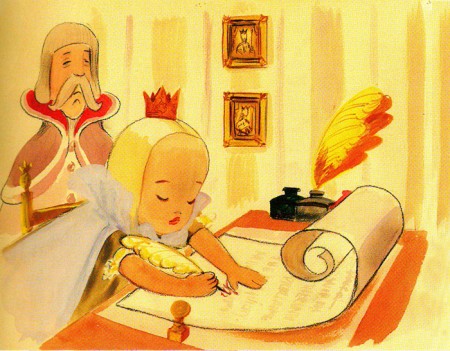

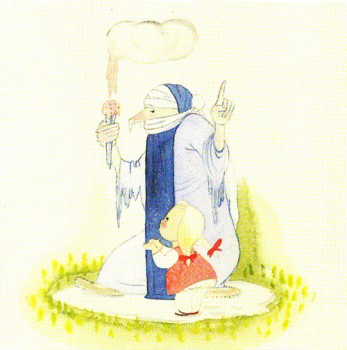

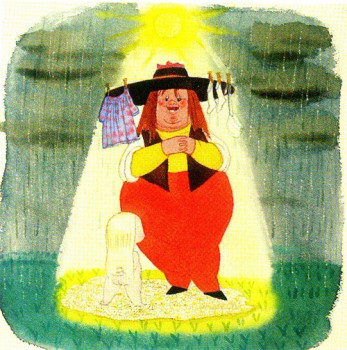

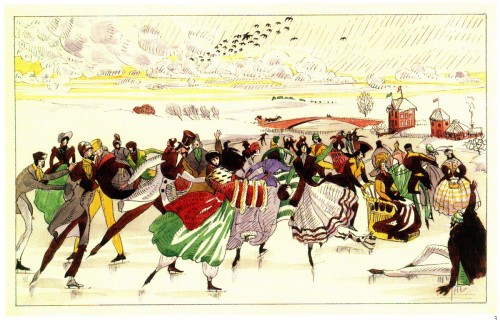

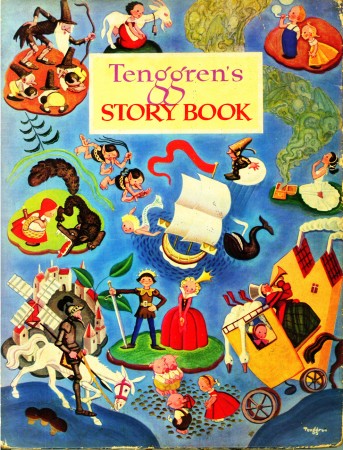

Tenggren’s Storybook – 1

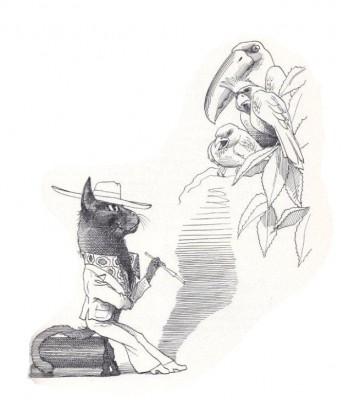

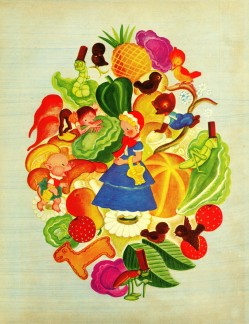

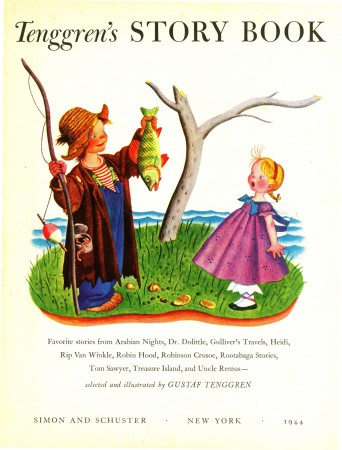

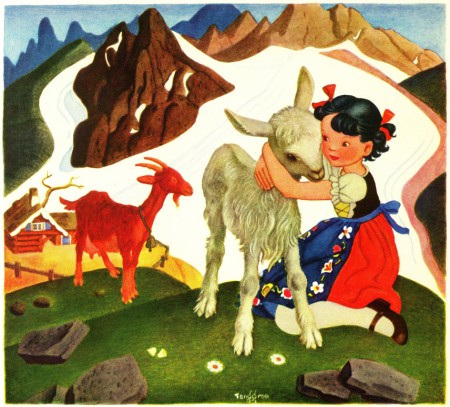

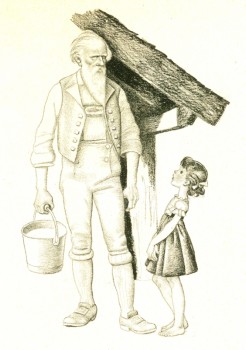

- Bill Peckmann sent me his copy of Gustaf Tenggren’s Story Book. This is an oversized book which adapts bits of well known children’s stories – a chapter of Heidi, another from Gulliver’s Travels, a story from the Uncle Remus Tales, etc.

Tenggren, of course, illustrated them – sometimes with large color illustrations sometimes with spot drawings.

Lest you’ve forgotten, Tenggren was the illustrator brought by Disney to the studio to design Snow White’s forests and Pinocchio’s landscapes. After Disney, he went to work illustrating and writing Little Golden Books – all the famous ones including The Poky Little Puppy.

Here is the first post of some of the Tenggren illustrations to the book:

The book’s cover

1

1

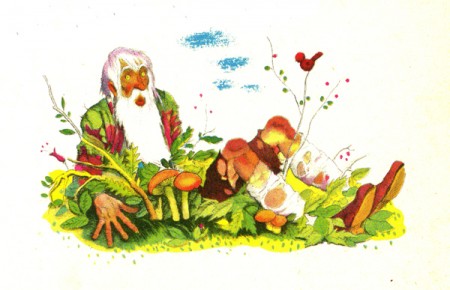

Chapter heading for Rip Van Winkle.

2

2

Only two illustrations for Doctor Doolittle, but

they’re beautifully abstract.

1

1

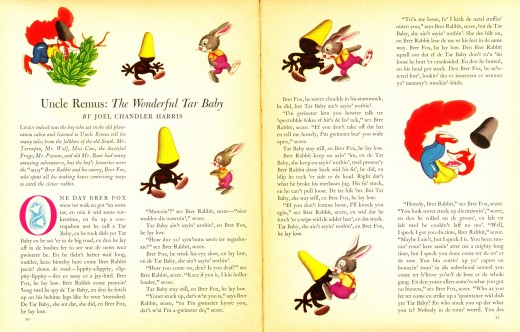

The layout is so nice for The Tar Baby,

that I’m posting the full double page spread.

Many thanks to Bill Peckmann. I’ll post more of these upcoming.

Books &Illustration 24 Jun 2010 08:41 am

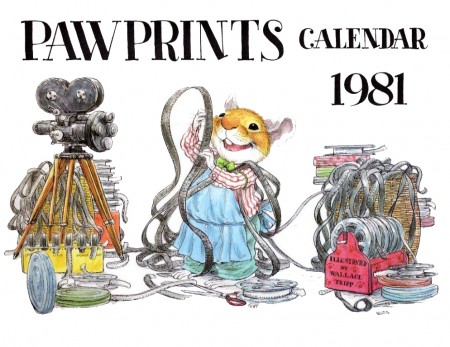

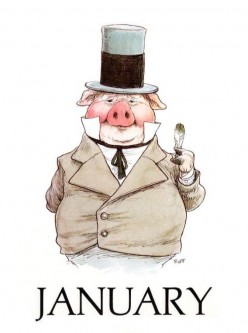

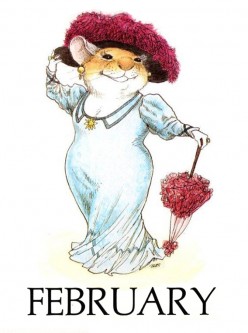

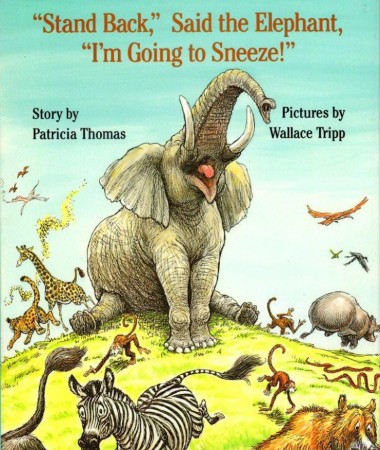

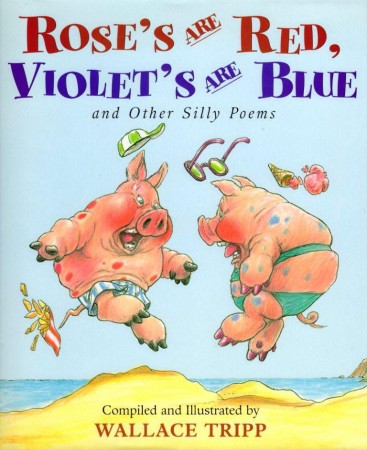

Wallace Tripp 1981

Articles on Animation &Books &Commentary 19 Jun 2010 09:05 am

Happy belated Birthday, Mike

- This past Tuesday, Amid Amidi celebrated the birthday of Mike Barrier with a very respectful commentary on Cartoon Brew. This was followed quickly by more kind words and an acutely written article on Mark Mayerson’s excellent blog. Both were met with positive comments from the people following the two sites.

- This past Tuesday, Amid Amidi celebrated the birthday of Mike Barrier with a very respectful commentary on Cartoon Brew. This was followed quickly by more kind words and an acutely written article on Mark Mayerson’s excellent blog. Both were met with positive comments from the people following the two sites.

I was pleased to see both posts and thought of leaving my own comment on each of them. However, I have my own blog and have probably too much to say.

Mike and Phyllis Barrier are very dear friends to me. When they lived in Washington D.C. I took many weekend trips to see some art exhibit or special film event or just a visit to meet with them. We grew close, and even though now we’re half a continent away, I still feel there’s something dear and special about our friendship.

However, long before we became friends, I was a fan of Mike’s writing, criticism and commentaries about the world of animation. Those early issues of Funnyworld Magazine became seminal to my knowledge about the history of the medium. I also knew inherently that this was a widespread thing. Anyone who was anyone, student or professional, knew the magazine. I remember going to my first animation festival – Ottawa ’76. I witnessed no fewer than three conversations about Chuck Jones vs Bob Clampett, all precipitated by a couple of pieces in Funnyworld. No matter how ludicrous it all seems now, Mike had inadvertently reignited something of a feud in Hollywood between the two directors even though he wrote that Jones and Clampett were both brilliant.

The magazine made a large foothold among all animation-lovers. Eventually, it, like most small and independently published magazines, suffered financially until it had to be stopped. Back issues are still being sold for enormous amounts of money.

Mike kept pushing ahead for years and years and years on his book, a history of Hollywood animation and it was always a treat for me to discuss it with him. Like many other people, I panted for the day when the book would finally make it to the stores. Once Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age was published, I immediately plowed through it, then started over and read it again. I’ve re-read the book every year since. It’s the pinnacle of animation history, in my opinion. There’s nothing as exacting or precise or historically accurate on the market.

Mike kept pushing ahead for years and years and years on his book, a history of Hollywood animation and it was always a treat for me to discuss it with him. Like many other people, I panted for the day when the book would finally make it to the stores. Once Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age was published, I immediately plowed through it, then started over and read it again. I’ve re-read the book every year since. It’s the pinnacle of animation history, in my opinion. There’s nothing as exacting or precise or historically accurate on the market.

I also remember a point when Mike was hired to write a history of Warner Brothers cartoons. During one visit to his home in Alexandria, he surprised me by handing me the manuscript and asking me to read it. That was one of the fastest reads I’ve gone through. Excellent, of course; I was properly overwhelmed. On another day, he opened a draw of large-sized chromes of WB artwork. BG’s and animation drawings photographed beautifully and sitting there for me to drool over. It was a treasure-filled weekend for me. The book was cancelled by Warners when they suddenly had a power shift, and a piece of brilliant historical writing was lost. I’ve always hoped Mike would somehow rework that manuscript so that the ultimate history of WB would be made public.

The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney, is equally brilliant, even though it seemed to disappoint some animation people. The book follows the story of Walt Disney, the man – just as the title states. It took its subject seriously, and when Walt lost interest in animation, so did the book. We learned more about Fess Parker, Treasure Island and the theme parks than we ever expected from a book about Disney. And, realistically, that’s the way it should have been. Mike painted a portrait of a unique man, and it made him human. Something that hadn’t been attempted before – except by some detractors who tried to make their names by slandering Walt and finding the most negative stories they could concoct.

The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney, is equally brilliant, even though it seemed to disappoint some animation people. The book follows the story of Walt Disney, the man – just as the title states. It took its subject seriously, and when Walt lost interest in animation, so did the book. We learned more about Fess Parker, Treasure Island and the theme parks than we ever expected from a book about Disney. And, realistically, that’s the way it should have been. Mike painted a portrait of a unique man, and it made him human. Something that hadn’t been attempted before – except by some detractors who tried to make their names by slandering Walt and finding the most negative stories they could concoct.

Aside from these two books, Mike wrote Carl Barks and the Art of the Comic Book, a history of Barks and the amazing comic books he wrote and illustrated for Disney. Mike has also coauthored, with Martin Williams, The Smithsonian Book of Comic Book Comics, a complete history of the comic page characters that developed into long-running comic books. It’s a big book with lots of well-produced color comic pages. The comic pages are printed on the same newsprint that the originals were printed on.

Aside from these two books, Mike wrote Carl Barks and the Art of the Comic Book, a history of Barks and the amazing comic books he wrote and illustrated for Disney. Mike has also coauthored, with Martin Williams, The Smithsonian Book of Comic Book Comics, a complete history of the comic page characters that developed into long-running comic books. It’s a big book with lots of well-produced color comic pages. The comic pages are printed on the same newsprint that the originals were printed on.

Oh, yes, he also has a great website.

Now, Mike has turned 70 and seems to be in high form. I know he’s working on a couple of other books and I anxiously await getting them in my hands. Mike’s a friend, a good friend. Aside from that he’s a great and knowledgeable writer of animation. Even when I don’t agree with what he has to say, his writing makes me think about my medium and pushes me to think deeper. (A good example of this is his review of Get To Know Your Dragon which pointed out that we’ve lost something since the glorious Fanny trilogmade in the early thirties. It got me to think seriously about how to bring back that slower paced aura from the past, the one that allowed characters to develop – really develop. Not in the clichéd way of today’s animation but in the full and deep way of the films of the golden era.)

Many like to put down Mike’s writing for being too negative. I know it isn’t. I know that most other writing is too accepting, too forgiving. Has there been a serious review of Toy Story 3? I only see glowing reviews for an amazingly clever film that whisks us through a hurly-burly of confusion until the sappy moments at the end. No characters properly developed, or enlarged. Just whirlwind story – very cleverly done. We need better film critics, not just animation critics. Ironman II isn’t ok, nor is The A Team, nor is Shrek 4. They’re franchises not movies. MacDonald’s III. Yes, aspects of them all are fun, but that’s not enough. We need good movies that are better than clever, and we need more reviewers like Mike Barrier. Those whose historical accuracy is above and beyond most others and whose taste is shaped by a history of watching many many films as well as by a strong understanding of the medium. He knows what he’s writing about, is not afraid to say it, and I’ll follow him anywhere.

Happy Birthday, Mike Barrier, may you have many more.

Bill Peckmann &Books &Disney &Illustration 12 Jun 2010 08:06 am

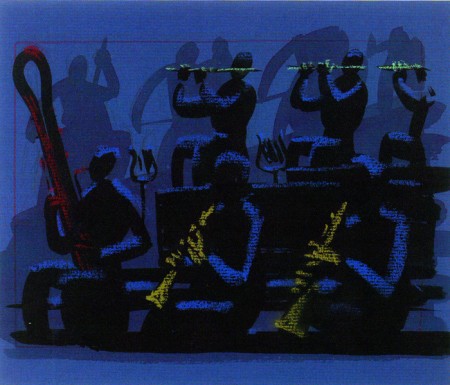

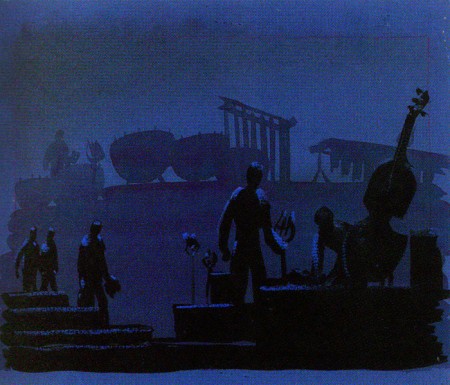

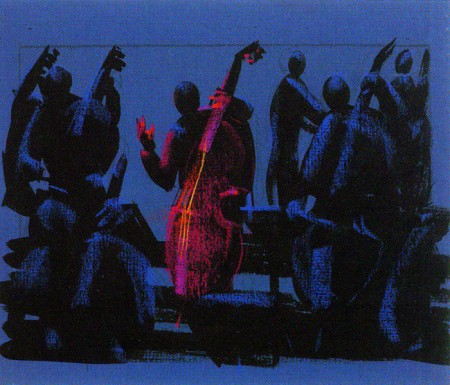

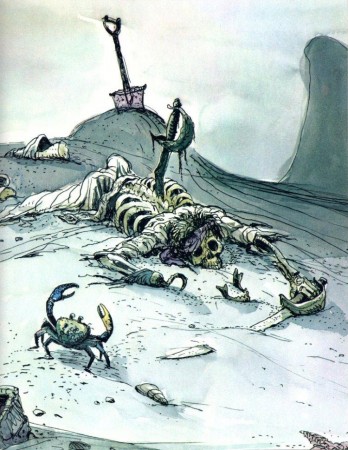

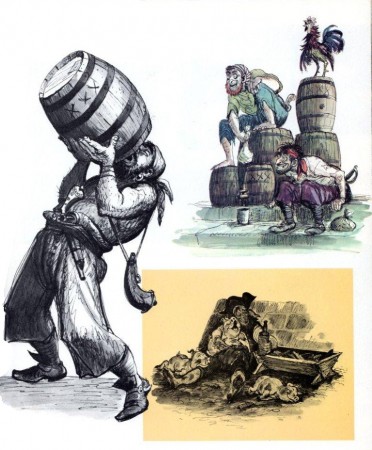

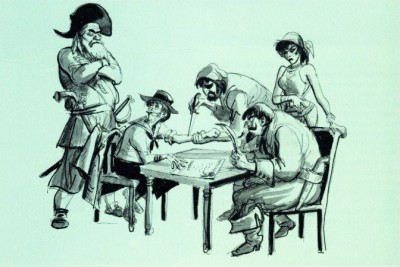

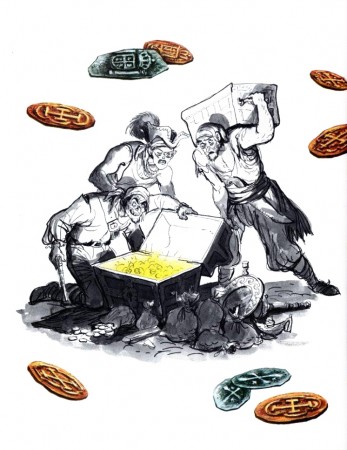

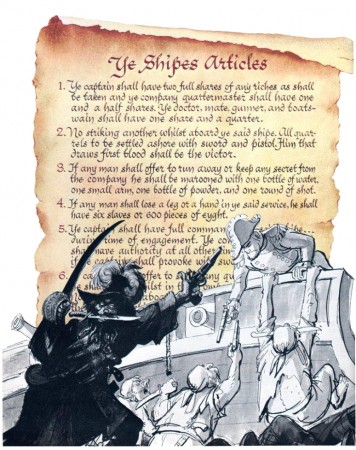

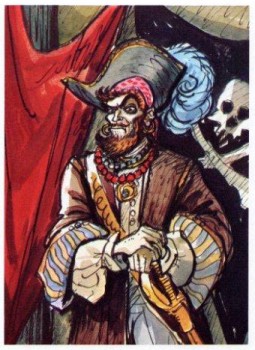

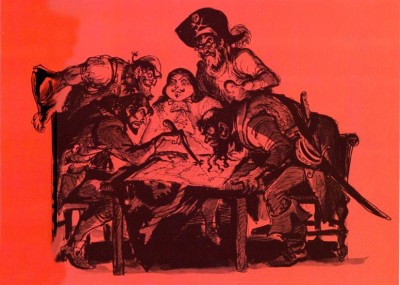

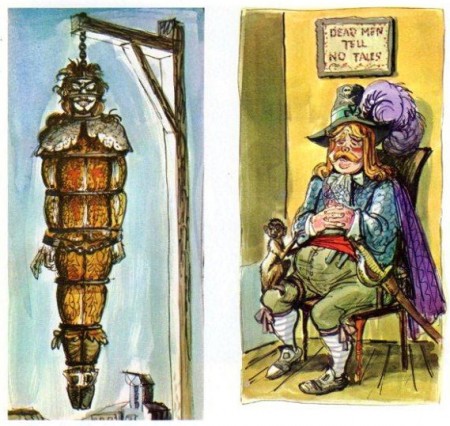

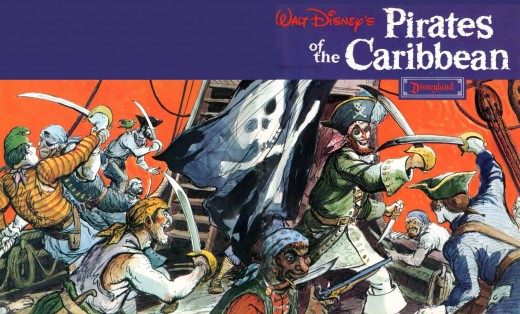

Marc Davis’ Pirates – 1

Marc Davis illustrated a “Pirates of the Caribbean” souvenir paperback book for Disneyland. Bill Peckmann, naturally, saved his copy of the book and has forwarded these illustrations from the book. I’m a fan of Davis’ work, so love sharing them with you.

Davis did quite a few illustrations for this ride and others of them can be found here and here.

More thanks to Bill Peckmann.

The wrap-around book cover.

I still have another whole post of these drawings and will put the m up tomorrow.

Bill Peckmann &Books &Illustration 04 Jun 2010 06:47 am

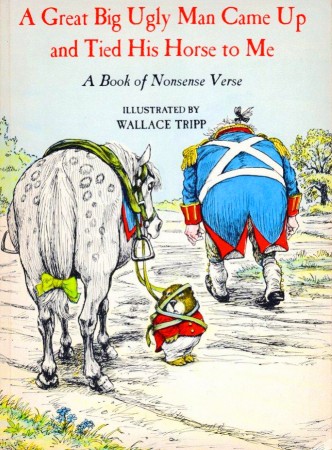

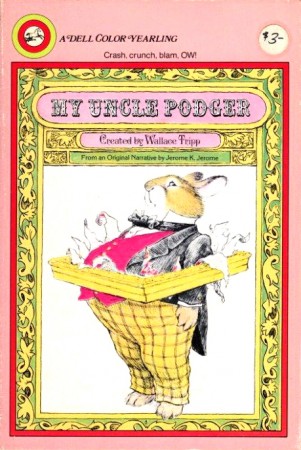

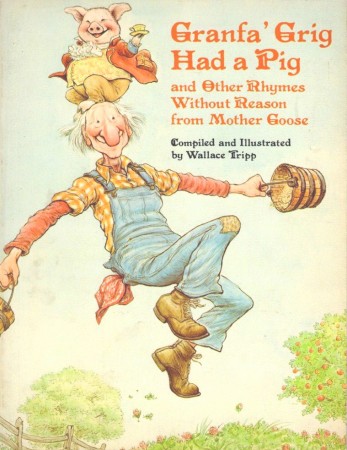

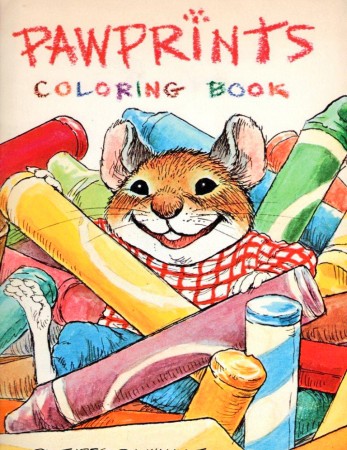

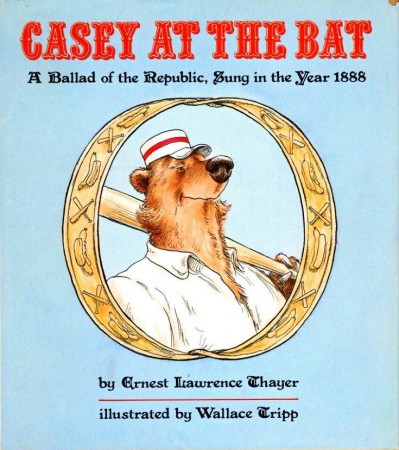

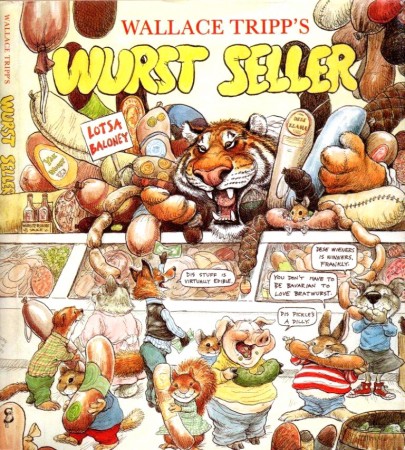

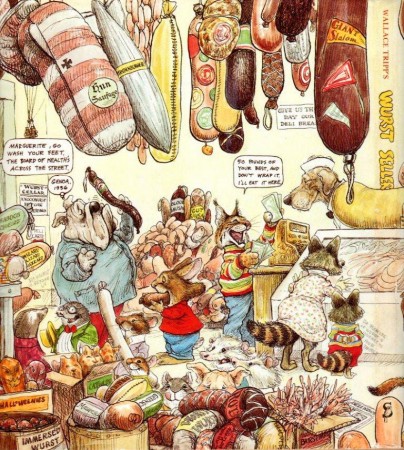

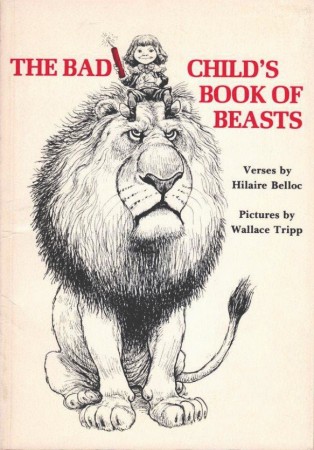

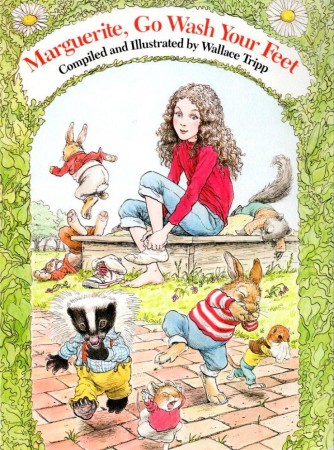

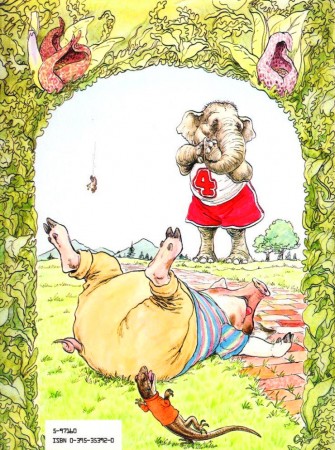

WT Bibliography

- Wallace Tripp‘s illustrations have gotten a bit of attention here, so Bill Peckmann followed up his other pieces with a row of book covers that Tripp illustrated between 1972 and 1999. (There are many other books not included here, but these are plenty to give an idea of the man’s scope and range.)

Many thanks to Bill Peckmann for putting these all together.

1972

1972

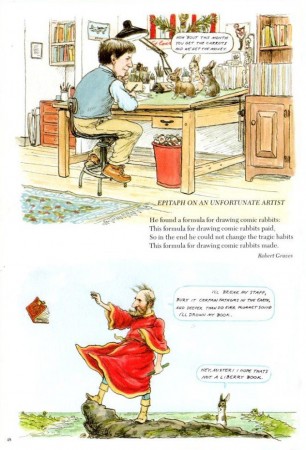

The guy sitting at the dest at the top of this page of

Marguerite is a self-caricature of Wallace Tripp.

Bill Peckmann &Books &Illustration 02 Jun 2010 08:21 am

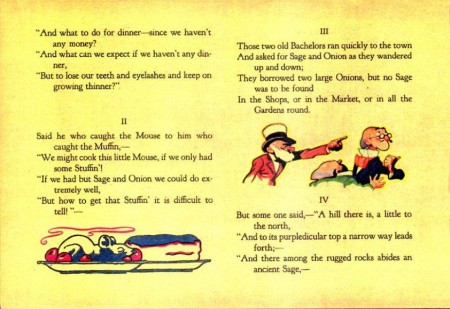

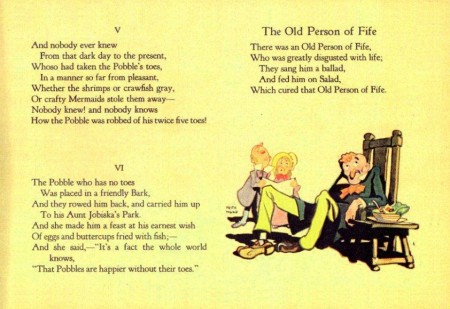

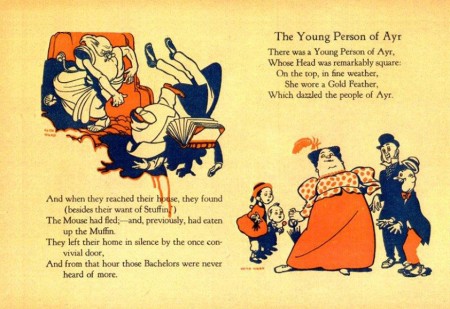

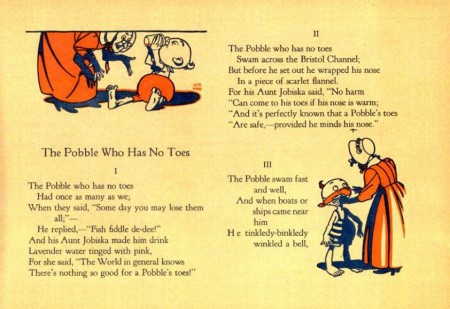

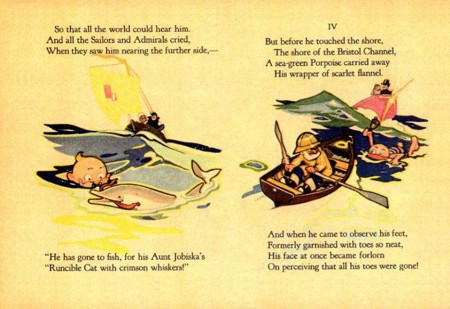

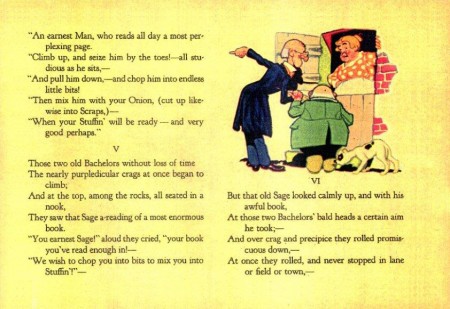

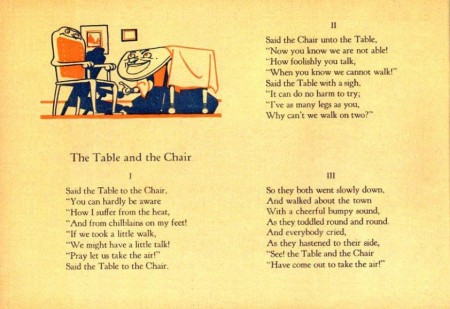

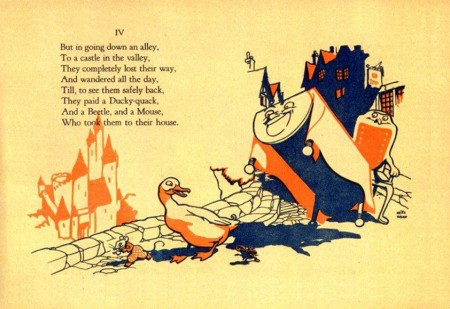

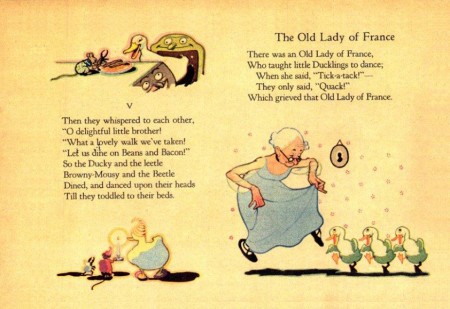

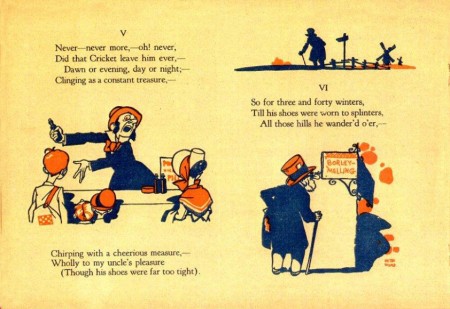

Edward Lear Nonsense – 2

- Last week I posted the first half of this book by Edward Lear of his Nonsense poems which was illustrated by Keith Ward. There’s not a lot known about Ward, however I did receive a nice email from Wilbert Plijnaar

which gave me a couple of links and some info. I’ll post that letter at the bottom of the post.

Here’s the rest of the book thanks to the gracious generosity of Bill Peckmann.

20

20

Here’s that email, from Wilbert Plijnaar:

- A few years back fellow story board artist Harry Sabin allowed me

to make copies of a book he had (then) recently purchased ,

illustrated by Keith Ward : “Reynard the Fox”

I was so impressed by the Disneyesq / Walt Kelly- ish, style I found it impossible to believe the artist wasn’t more well known in animation circles.

I showed copies on the Cartoon Retro – and Dutch comic maker blog (both gone) for more information. We found there are many illustrators named Keith Ward , who all have different styles.

Through intensive mouse clicking I was led to some advertising illustrations that looked to be from the same artist ( see below) , learned Ward was amongst other , responsible for the “Dick and Jane ” and “Black Stallion” Illustrations and died in Florida on March 23, 2000 .

Dutch/French comic artist Evert Geradts pointed out that the signature of a landscape painter with the same name was identical to the Keith Ward from Reynard the Fox.

http://www.stewartgalleries.com/paintings.htm

(In the mean time the gallery seems to have taken the paintings offline but maybe they still have an archive?)

Some of the Reynard scans I put on Imageshack still survive, as does one of the commercial illustrations:

If you would like to see the 4 or 5 missing illustrations I will gladly scan them again for you.

Doing a renewed Google search after reading your blog, led me to a Leif Peng’s blog post from 2007 and a more recent one, with many examples and info about Ward.

http://todaysinspiration.blogspot.com/2007/10/keith-ward-1906-2000.html

and

http://todaysinspiration.blogspot.com/2009/06/keith-wards-texaco-fire-chief-pups.html

other links:

http://www.askart.com/askart/w/keith_ward/keith_ward.aspx

http://www.worthpoint.com/worthopedia/vintage-elsie-the-cow-cook-book-1952-ill-by-keith

Thanks to Wilbert.