Category ArchiveBooks

Books &Daily post &Hubley 28 Sep 2011 07:33 am

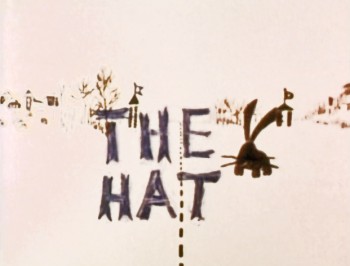

The Hat – even Bigger

As I wrote on Monday, with the AMPAS show about Hubley animation coming this Oct 10th, I intend to put a lot of focus on the work of John & Faith. This piece about THE HAT was originally posted in March, 2011. I’ve added to it.

- The interview Mike Barrier conducted with John Hubley has me thinking about Hubley and my years back there and then. You might say, I’m in a Hubley frame of mind these past few days, so I’m into reminiscing. I posted part of this back in March, 2008; here, I’ve extended the article a bit.

New York’s local PBS station, WNDT – that’s what it was called in the old days – used to have a talk show hosted by film critic, Stanley Kaufman.

New York’s local PBS station, WNDT – that’s what it was called in the old days – used to have a talk show hosted by film critic, Stanley Kaufman.

(It turns out that this show was produced by the late Edith Zornow, who I once considered my guardian angel at CTW.)

This talk show was quite interesting to me, a young art student. I remember one show featured Elmer Bernstein talking about music for film. He gave as his example the score for The Magnificent Seven. He demonstrated that the primary purpose of the score, he felt, was to keep the action moving, make the audience feel that things were driving forward relentlessly. I still think of that show whenver I see a rerun of the film on tv.

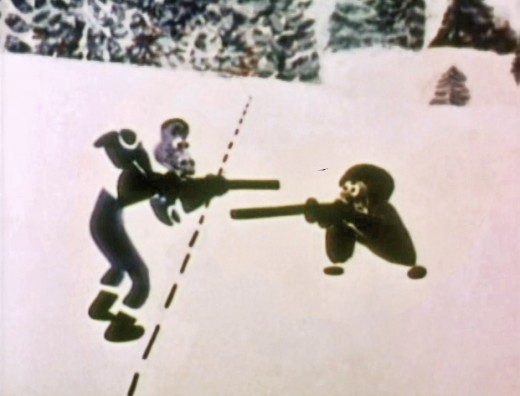

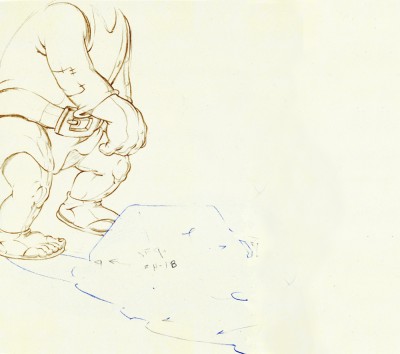

The surprise and exciting program for me came when John and Faith Hubley turned up on the show to demonstrate how animation was done. They were using as an example a film they had currently in production, The Hat. This film was about the silliness of border lines. One of two guards, protecting their individual borders, loses his hat on the other side of the line. Of course, all he needs do is to step over and pick up the hat, but he can’t. The other guard won’t allow him to cross the border illegally – even to pick up his hat.

The voices were improvised by Dudley Moore and Dizzy Gillespie (much as the earlier Hubley film, The Hole, had been done.) The two actor/musicians also improvised a brilliant jazz score.

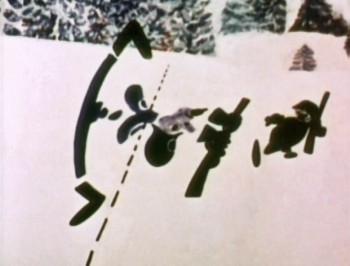

John’s design was quite original. The characters were a mass of shapes that were held to-gether by negative space on the white on white backgrounds.

The animation of the two soldiers was beautifully done by Shamus Culhane, Bill Littlejohn, Gary Mooney and “the Tower 12 Group“.

The animation of the two soldiers was beautifully done by Shamus Culhane, Bill Littlejohn, Gary Mooney and “the Tower 12 Group“.

Culhane animated on a number of Hubley films during this period, most notably Eggs and a couple of commercials.

Bill Littlejohn animated on many of the Hubley films from Of Stars and Men up to Faith’s last film.

Gary Mooney animated on The Hole and Of Stars and Men. He was an Asst. Animator at Disney, animated for Hubley then moved on to some of the Jay Ward shows before moving to Canada where he continues to animate.

Tower 12 was the company formed by Les Goldman and Chuck Jones at MGM. Apparently they were between jobs when Hubley was finishing this film, and Chuck offered help.

Of course, the colors of the film as represented by the dvd are pathetically poor.

It’s hard to even imagine what the actual film looks like, and it’d be great to see

a new transfer of all the Hubley films.

The design style of the film was an original one for 1963. It’s one that would often be copied by other animators afterwards. The characters were searated at their joints. No reel ankles, just open space. They were also broken at the wrists and belts. The taller man seems to have a collection of ribs and shoulders for his torso. Like the dotted line they walked but could not cross, these people were also a gathering of parts.

The design style of the film was an original one for 1963. It’s one that would often be copied by other animators afterwards. The characters were searated at their joints. No reel ankles, just open space. They were also broken at the wrists and belts. The taller man seems to have a collection of ribs and shoulders for his torso. Like the dotted line they walked but could not cross, these people were also a gathering of parts.

This was one step removed from the earlier film, The Hole, which had just won the Oscar and went on to enormous success for the Hubleys. That film used what they called the “resistance” technique. They first colored the characters with a clear crayon. Ten painted watercolors on top of that. The crayon would resist the watercolor and a splotchy painterly style developed. The Hat literally broke those splotches into parts of the characters and put some of the control in the animators’ hands.

This was one step removed from the earlier film, The Hole, which had just won the Oscar and went on to enormous success for the Hubleys. That film used what they called the “resistance” technique. They first colored the characters with a clear crayon. Ten painted watercolors on top of that. The crayon would resist the watercolor and a splotchy painterly style developed. The Hat literally broke those splotches into parts of the characters and put some of the control in the animators’ hands.

.

The film was obviously political. Anti-nuclear politics played strongly in the story. This was a step just beyond The Hole. In that film, two sewer workers converse on what violent things might be happening above ground. The film ends with an accident, or possibly a nuclear crash.

The film was obviously political. Anti-nuclear politics played strongly in the story. This was a step just beyond The Hole. In that film, two sewer workers converse on what violent things might be happening above ground. The film ends with an accident, or possibly a nuclear crash.

In The Hat, the two partisan soldiers discuss a history of man’s aggression all within their reach. At one point, it would seem, each of

them is ready to press the red button calling for nuclear assistance – or, at the very least, a buildup of military force.

them is ready to press the red button calling for nuclear assistance – or, at the very least, a buildup of military force.

While walking up and down that line, they comment on how we reached the point of no return. All the while, bugs and small animals cross the line, indeed, walk on or over the “hat” lying on the ground.

The backgrounds for this history of War grow more violent, more expressionist. John’s painterly style comes to the fore, and the brush strokes take on a force we haven’t seen to this point.

When we return to the two leads, we find that they’ve changed. They’re darker, and they both have lines scratched into the paint of their bodies. Not as much emphasis is placed on their disjointed body parts.

We leave them as we found them, walking that line. At this point, both of their hats lay on the ground and they’re deep into conversation. They don’t seem to notice anymore.

It has started to snow.

.

.

Shamus Culhane wrote about The Hat in his autobiography, Talking Animals and Other People. Here’s some of what he wrote:

- In 1964 the Hubleys wrote a short subject called The Hat. It was subsidized by an international peace organization. The picture featured two sentries marching on opposite sides of a boundary line. A clash occurs when one soldier’s hat accidentally rolls into enemy territory, and the other soldier refuses to return it until he has checked on the necessary protocol. During the ensuing discussion the two men become friendly, and the film ends on an optimistic note.

Although there were other characters and animals in the picture, the two soldiers accounted for about 80 percent of the footage. When Hubley asked me if I could do all of the animation of the sentries myself, I jumped at the chance. The last time I had drawn full animation, other than one-minute spots, was about twenty years before, when I worked with Chuck Jones at Warners.

The Hubleys were exciting to work with because they had a strong sense of adventure in their filmmaking. John was never tied down to techniques that he was already familiar with. Each picture was a new experience, because the appearance of the film was always dictated by the content. The Hat was no exception.

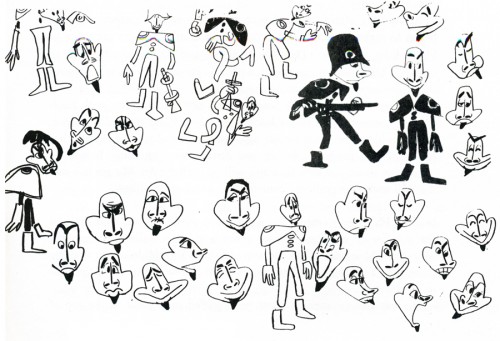

The design of the two sentries presented some odd problems in animation, in that the action was going to be normal, but the arms and legs were not attached to the bodies. Although we had detailed model sheets of each soldier, Hub’s layouts paid scant heed to his original designs. As the picture progressed his drawings of one of the soldiers became more and more Christ-like.

While I animated the picture at home, Hubley and I worked very closely together. Whenever I had a few scenes finished, we would have a conference on this work and the following scenes. Hubley was a very enthusiastic director. He would pick up the newly animated shots with obvious excitement, flip the drawings, and burst out laughing. His pleasure was so infectious that I would laugh, too. We shared a feeling of joy in the whole process or filmmaking.

The animation of The Hat took many months. During that time, with my usual curiosity about the working methods of great artists I have worked with, I studied Hubley’s approach whenever I could. In the first place he worked in a room that was crammed with the largest collection of art books I have ever seen in private hands. The subjects ranged from prehistoric cave paintings to Picasso, Klee, Chagall, and other modern artists. There were books on the art of every culture imaginable, Aztec, Mayan, Chinese, Persian, Greek, etcetera.

At the beginning of a picture Hubley would pore over a random selection of art books. Seemingly they had no relationship to each other, but he was using them to inspire his own sense of design. However, the final appearance of a Hubley film was never blatantly derivative. In The Hat, for example, I have the feeling that he was influenced (if that is the right term) by Chinese scroll painting, but that is just my own intuition.

Since Hubley was going to paint his own backgrounds, the layouts were usually little more than a vague series of scrawls with little or no detail, unless the background and the animation were going to be closely related.

Unlike Disney Studio, where the dialogue is broken down for the animator in meticulous detail, Faith gave me a very loose track analysis. Neither Faith nor John seemed to be concerned with precise synchronization of the mouth action and the dialogue track.

John’s instructions for the movement of the characters were also very loosely indicated on the exposure sheets. It seemed to be his feeling that the pace of the animation should be the shared responsibility of both the director and the animator.

The Hubley children had to be the luckiest kids in New York City. Not only were they encouraged to draw, write, and paint, but in their Riverside Drive apartment the Hubleys had built a small stage, so it must have been easy for the family to create the sound tracks for such imaginative films as Moonbird, Windy Day, and Cockaboody.

Like John Cassavetes, the Hubleys believed in the value of ad-libbing sound tracks, so a good deal of the children’s dialogue in these pictures was completely spontaneous material.

Whatever his formal education had been, Hubley was a very well-informed person, with a sophisticated view of life. One Saturday morning I dropped in to find John working alone, and in a very depressed mood. It happened that I was on the down side myself that morning. After we had talked over the work in the new scenes, our conversation drifted off into a very open discussion about the problem of being an alienated personality. We exchanged anecdotes about incidents that had happened to us because of alienation.

Somehow our talking acted as a catharsis, and we both found our moods lightened. We ended up laughing, and agreed that being alienated in our kind of society had more merit than most people realized. It was a very stimulating discussion.

Books 20 Sep 2011 07:35 am

Overdue Book Review – Talking Animals

- Back in 1986, Shamus Culhane sent me a copy of his new autobiography, Talking Animals and Other People. I properly sent him a thank you note, and have to admit that I put the book aside and didn’t get to read it. All these years later, I have finally read it and thought I give some comments on the book.

- Back in 1986, Shamus Culhane sent me a copy of his new autobiography, Talking Animals and Other People. I properly sent him a thank you note, and have to admit that I put the book aside and didn’t get to read it. All these years later, I have finally read it and thought I give some comments on the book.

Shamus and I were never close. He always seemed, to me, so full of himself that I had a hard time getting past the image he tried to put across. It all climaxed with a serious argument we had when I was on the Executive Board of the animator’s u-nion, Local 841, in NY. Shamus was starting a studio in NY to produce the sequel to the show he had done in Italy, Noah’s Animals. This one was to be called King of the Beasts. He came to the Board to add an amendment to the contract. He felt that animators would work on a scene and quite often not heed the director’s instructions and incorrectly animate the scene. He wanted the right to ask for the scene to be reanimated at no charge. The Board, in asking questions about the proposal, seemed not too pleased with the idea. Somehow it came to an argument between me and Shamus, however civil,

over this idea. I asked how many times was the animator to redo the scene for the Producer without getting paid; the notion seemed so Producer-sided that I couldn’t believe that Shamus was requesting this proviso. The Board voted it down.

over this idea. I asked how many times was the animator to redo the scene for the Producer without getting paid; the notion seemed so Producer-sided that I couldn’t believe that Shamus was requesting this proviso. The Board voted it down.

After that, Shamus wouldn’t talk to me again whenever we met in NY. He came to the Raggedy Ann studio several times that year but refused to say hello to me again. Oh, well. However, he did send me a copy of his book.

And I read it this past week. Finally.

I have to say it started Gangbusters for me. I just zipped on into the book and loved every second of it. Here was a guy who had lived through the early days of silent animation and continued working for some of the best. Bray, Fleischer, Iwerks, Van Buren and Disney  followed by animation for Jones and direction for Lantz before opening his own studio to make TV commercials and shows. After several years of success he went bankrupt, then he animated for Hubley and ran Paramount, finally producing a couple of odd one-off TV programs. The man had done just about everything. And it’s in the book.

followed by animation for Jones and direction for Lantz before opening his own studio to make TV commercials and shows. After several years of success he went bankrupt, then he animated for Hubley and ran Paramount, finally producing a couple of odd one-off TV programs. The man had done just about everything. And it’s in the book.

There’s a first-hand account of all these studios that, if nothing else, serves as strong corroboration about how those studios were run – in some detail. The reader rides along with Culhane, almost feeling as though you were there with him. His story is so well told and written that it almost reads like a rousing Mark Twain action yarn about early animation. It flows. Of course, it’s all from the POV of Culhane, so there may be some bias,

but, factually, the first half of the book seems pretty accurate. I can’t vouch for the second half when Culhane talks about his own studio. Some of the work at that studio included the Ajax elves, Around the World in 80 Days credits, the dancing Muriel Cigar, as well as Hemo the Magnificent and other Bell Science series shows. It’s an impressive list of credits, if you know any of the films.

but, factually, the first half of the book seems pretty accurate. I can’t vouch for the second half when Culhane talks about his own studio. Some of the work at that studio included the Ajax elves, Around the World in 80 Days credits, the dancing Muriel Cigar, as well as Hemo the Magnificent and other Bell Science series shows. It’s an impressive list of credits, if you know any of the films.

The first half of the book, through the Warner Bros. section, is just great. If you know any part of this animation history, this book will fill gaps you may have. Once I got to the Lantz section then through to the end of the book, Shamus Culhane’s ego entered and seemed to keep growing. Perhaps it’s a well deserved ego, but it did present something of a problem for me . . . a hiccup every time I stumbled over it.

But the book is eminently readable, and I heartily recommend it to everyone interested in animation. It’s not only informative but fun.

Books 30 Aug 2011 07:26 am

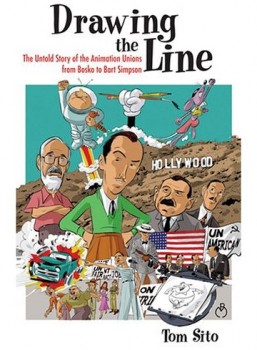

Overdue Book Review – Tom Sito’s Drawing the Line

- There are a number of books I have been remiss about reviewing. For different reasons I’ve not been able to get to reading or reviewing or even commenting on several excellent books. I’ve decided to try to catch up with some of the more important ones.

- There are a number of books I have been remiss about reviewing. For different reasons I’ve not been able to get to reading or reviewing or even commenting on several excellent books. I’ve decided to try to catch up with some of the more important ones.

Note: I also have a problem with WordPress I am having difficulty resolving. It won’t allow me to save any post that has the word “u-nion” in it. I have to add the hyphen to get by with it. Since this book is about u-nions, please expect and forgive a lot of hyphens.

- Tom Sito‘s excellent book, Drawing the Line, is, to me, something of an important book. Other than Karl Cohen’s 1997 book, Forbidden Animation: Censored Cartoons and Blacklisted Animators in America, this is the only book to talk in depth about the Hollywood labor problems and the effect of the McCarthy-era blacklisting on animation. The politics of the different periods is crucial to the subject, and Tom Sito takes that in with ease clearly addressing the subject at hand.

My favorite chapter of the book comes at the beginning. Tom Sito has a charm and a wit in his style, and it comes across most abundantly here. He details lots and lots of small injustices the bosses have against the labor force. It’s all told with such humor, that it takes a while for the heinous conditions being described to be driven home.

I imagine it was no mean feat to give both a history of animation, for those who are unfamiliar with it, and, at the same time, to go into depth with very specific data that breaks down the conditions and the actions that caused the strikes. There are three attempts at

I imagine it was no mean feat to give both a history of animation, for those who are unfamiliar with it, and, at the same time, to go into depth with very specific data that breaks down the conditions and the actions that caused the strikes. There are three attempts at

u-nionizing analyzed with detail within the book. _____ Fleischer strikers in front of the Fleischer studio, NYC, 1937. *

Smaller actions like

the Van Buren and Schlesinger studio strikes are dealt with in short order. The Fleischer, Disney, and Terrytoons strikes take whole chapters to review. All three created enormously heavy feelings felt by the participants even to the end of the century, though the actions had happened more than fifty years earlier. I’d witnessed conversations with members who were holding angry grudges against other members, whether because they had been scabs or had been participants in the u-nion organizing. Sito’s book gives clear descriptions of this and the reasons that caused the friction.

The Blacklist and the Hollywood Wars are likewise detailed and broken down in specifics. Though I’d had an interest in this period of animation history some of the book’s stats are new to me. I also like Sito’s discussion of the aftermath of the period – an anti-political wave that kept people from speaking their mind about their politics. It seems like a simple observation, but it’s obvious only after it’s relayed.

My second favored chapter comes as the book goes in the second half. “Lost Generations” sees into the latter half of the Twentieth Century after the “Big Five” studios have been u-nionized. Here we look into smaller studios from Clampett to Jay Ward to Ralph Bakshi. Depatie-Freleng to Chuck Jones. We see how a ___ LtoR: Sylvia Cobb, unknown, Mary Tebb, Phyllis Craig (seated)later generation of ________and Ann Lord. Ink & Paint women at Disney, 1957.*

My second favored chapter comes as the book goes in the second half. “Lost Generations” sees into the latter half of the Twentieth Century after the “Big Five” studios have been u-nionized. Here we look into smaller studios from Clampett to Jay Ward to Ralph Bakshi. Depatie-Freleng to Chuck Jones. We see how a ___ LtoR: Sylvia Cobb, unknown, Mary Tebb, Phyllis Craig (seated)later generation of ________and Ann Lord. Ink & Paint women at Disney, 1957.*

artists have less of a

connection to the u-nion, and this sets us up for the big chapter, “Animation and the Global Market.” Here we see the mega-money step in and just about wipe the art off the face of animation. We see how the employees turn on their own u-nion and allow the studios to hae the upper hand. As Don Bluth moves to Ireland for financial incentives with lower salaries and Steven Spielberg settles in London to make his lower budget features. Disney sets up studios in Australia and Canada to produce low budget feature sequels and reap in high grosses at the box office. (Just today I saw a TV ad for the “Special edition” of Bambi II, years after its production. If only the film were “Special.”) Tom Sito is intimately involved in this chapter having been part of the picketing work force, and you can feel it in the writing. It feels personal.

Since he had been President of Local 839 for a while, I would have expected him to be partial to the u-nion but was pleased to see a very fair view showing both sides of the u-nion’s history – positive and negative. It’s an engrossing book, and I’m sorry I didn’t turn to it earlier.

The one negative I had with the book were the many niggling little errors throughout. Some examples include:

- pg 17 says: “Ub Iwerks, working alone, animated Walt Disney’s 1929 short The Skeleton Dance.” In fact, it was Plane Crazy that Iwerks animated alone with only some small assistance from Ben Clopton. In fact, Les Clark took particular pride in animating a scene of a skeleton playing the ribs of another skeleton as if it were a xylophone

- pg 26 reads: “Mary Blair had once been called by Walt Disney ‘the best artist in the studio.’ Within a year of Walt’s death she had resigned, perhaps as a result of professional jealousy of a woman with that much importance.” In fact, Mary Blair had resigned from the studio in 1953, even before Peter Pan, a film she had designed, had been released. She came back to work with Disney on designing a couple of exhibits for the NY World’s Fair and then supervised their move to Disneyland. She was devastated by the death of Disney and left several years later. Her problems with alcohol probably had more to do with the retirement than any “professional jealousy of a woman with that much importance.”

- pg 156 calls Bill Walsh the new president of IATSE. (I was curious to know if this was the same producer who worked at Disney for many years.) No, we learn on page 158 that it’s RICHARD Walsh who is the president of IATSE.

- Page 211 goes from calling William Weiss, Bill Weiss to Bob Weiss and back again.

I also was a bit annoyed with the Index which does not list quite a few names. Mary Blair, who is mentioned at least half a dozen times doesn’t get in the Index, nor does Preston Blair. Rudolph Ising and Hugh Harman don’t make it either, Bill Walsh (who is really Dick Walsh) gets listed on pg 156 & 202, although that name is Dick Walsh on 202. I stopped looking at the Index pretty quickly.

There are many other errors like this, though all of the large and detailed, specific data about the strikes and u-nions seems accurate. This book which is filled to the brim with facts dates and figures obviously has most of them correct. Perhaps the book’s copy editor should have been more questioning.

This is a strong book, and if you haven’t already read it, I have to encourage you to do so. It’s a very particular history, and it has a lot to offer that isn’t available in other animation history books.

- Tom Sito has also authored several other books:

- He is the author of the revised version of my favorite “how to” animation book, Timing for Animation. It was originally written by Harold Whitaker with John Halas attaching his name (he probably got the publisher and not much more). Tom updated the book to include the cgi world. (To be honest, I haven’t seen the book; I only know the original – very well. Consequently, I have a hard time saying much about the revised version.)

He also has co-authored with Kyle Clark. Inspired 3D Character Animation is designed to show how to put Character into 3D animation and not just set key frames.

* picture 1 courtesy of MPSC Local 839, AFL-CIO Collection, Urban Archives Center, Cal State Univ., Northridge

* picture 2 courtesy of Anne Guenther and Archives of the Animation Guild, Local 839, North Hollywood.

Animation Artifacts &Books &Commentary &Disney 11 Aug 2011 06:52 am

Response

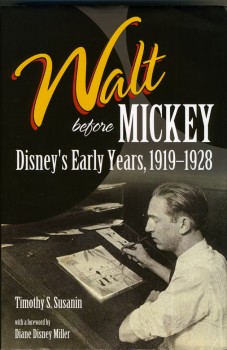

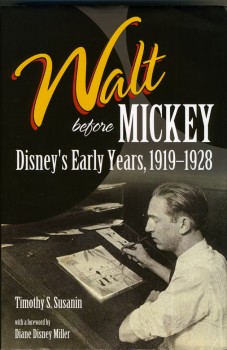

- On Tuesday, I’d posted a review of Timothy Susanin‘s excellent book, Walt Before Mickey: Disney’s Early Years 1919-1928. I loved the book and, in fact, worried that I was being too critical. I did tend to go on quite a bit about the details on details within the book.

To my surprise I’d received an email response from Mr. Susanin, and I asked him if he would mind my posting his letter. He immediately gave me permission and here’s his response to my review:

Dear Mr. Sporn,

Dear Mr. Sporn,

Many thanks for reading my book; for writing a review; and for your kind words.

I can’t tell you how much fun I had learning the story of Walt’s first decade. It was a most enjoyable and unexpected hobby, and I am sorry it’s over!

I am biased about Walt, of course, so I found the subject matter thrilling and a page turner, like you.

Your review is dead on in a number of respects. I am a Disney fan, not an animation expert, thus I was not equipped to search for the art, as were J.B. and Russell. Being a lawyer who has done many investigations, and written many detailed factual reports based on investigations, I was simply all about finding out what happened during Walt’s “missing decade.”

There was a reference in the Laugh-O-gram bankruptcy file to a studio “minute book,” and I would have been thrilled had a daily diary of any or all of that decade still existed! For me, following Walt day by day was the way to learn the real Walt and to see how he really got started.

So for me, a novice author and biographer — and maybe this notion would not be acceptable to other, experienced authors and biographers — there was real worth in learning all of the detail you mention in your review. Because no daily account existed, trying to find out at least what he was doing on a monthly basis helped bring this period alive for me.

The overload of detail — again, for me — allowed the physical spaces he occupied, the friends and colleagues, the look and feel of the period, the films produced to all come together and create a real portrait of that missing decade.

I agree that the question is: is this a viable biography for others outside this “niche market?” I didn’t set out to write a book, and once a book resulted, it was the book I would have wanted, because of the level of detail I wanted to know in order to really learn that period of Walt’s life. So, it worked for me!

And, as you point out, there were limitations. I had no budget. I had no publisher until the book was finished. I was not sure until near the end of the process that the Disney Company would provide photos.

So….this was very much a project where I was limited to take what others had done

and try to build on it, add facts to it, string things together, on my own and in my

spare time —- evenings and weekend.

I pulled all this together to learn about Walt in the 1920s. The info turned into a timeline that turned into a more detailed chronology that turned into a book. Along the way, I tried to find answers to whatever questions I had so that the blanks could be filled in.

I think what resulted is a work that I would have loved to come across in a book store or in a library, along with the realization that others would feel the same way, but maybe not a lot of others!

In the end, I got a real sense of who Walt was; what the first ten years of his career were like; how they set the stage for the rest of his career; and how a lot of his original collaborators fit into the big picture. It really sets the table nicely for me to now go on and read and learn about Walt in the 30s, 40s, etc.

In the end, I got a real sense of who Walt was; what the first ten years of his career were like; how they set the stage for the rest of his career; and how a lot of his original collaborators fit into the big picture. It really sets the table nicely for me to now go on and read and learn about Walt in the 30s, 40s, etc.

Unlike you, I did not want the book to go on. After six years and many rewrites and endless proofreading, I wanted it out the door and almost got sick of it! Maybe you can predict what happened after that: I now find myself wondering with increasing frequency about the spring of 1928, and what happened —- in a detailed way, on a daily or monthly basis! —- as Mickey appeared on the scene.

I thought that I would have nothing further to contribute to the Disney canon because, from Mickey’s appearance in 1928 til today, enormous amounts have been written about Walt’s story. Unlike the “missing decade” of the 1920s, the record is complete as far as the other decades of Walt career are concerned.

And yet….I find myself getting the urge to dig into the spring of 1928 and see where that takes me.

I don’t really know if I have another book in me, but my mind is starting to wander in that direction. I’ll keep you posted!

Many thanks again for your interest and your review.

Boy, do I hope he comes up with something about those several months between the start of Plane Crazy and the premiere of Steamboat Willie. Can you imagine the pressure on Walt and Roy? They’d just been robbed of their staff and had lost a semi-lucrative job doing Oswald cartoons. They create a mouse character, and no one wants the first short. So they do a second film starring Mickey, and still they can’t sell it. They do a third one trying to capitalize on the incoming sound transition. They show the film at one theater – for free – just to get it in front of an audience. Success! That short period is a tale in its own, and it’s never really been covered by writers.

In the photo, above: LtoR – Irene Hamilton (Inker), Rudy Ising, Dorothy Manson (Inker), Ubbe Iwerks, Rollin Hamilton, Thurston Harper, Walker Harman (Inker), Hugh Harman, Roy Disney. Walt took the photo.

On to something else that’s related. Mark Sonntag on his extraordinary blog, Tagtoonz, has posted some rarely seen photos of the first days of Disney’s filming in Kansas City. After posting the one photo of Walt directing and Red Lyon filming the Cowles children in 1922, he was contacted by a member of the Cowles family, and they offered additional photos. Take a look.

Action Analysis &Animation &Books &Disney &repeated posts 10 Aug 2011 07:07 am

Tytla’s Willie – recap

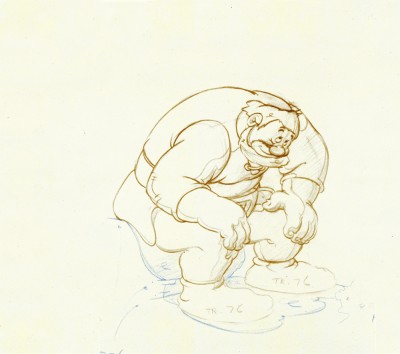

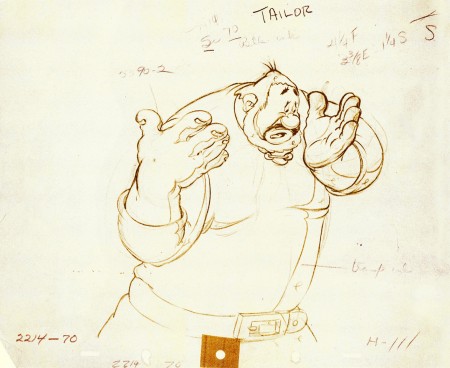

Continuing with my recap of all things Tytla, here’s a post I did on Tytla’s work on The Brave Little Tailor.

- When I was a kid, I was never a big fan of the “Willie” character, the giant in Mickey & the Beanstalk. It seemed that every fourth or fifth Disneyland tv show would have this character in it (or else Donald and Chip & Dale). As I got older and grew a more educated eye for animation, I came to realize how well the character was drawn and animated.

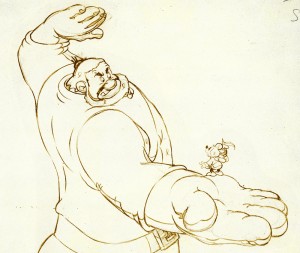

Willie first appeared in the classic Mickey short, The Brave Little Tailor, and he appeared fully formed. Bill Tytla was the animator, and he appeared to have fun doing it.

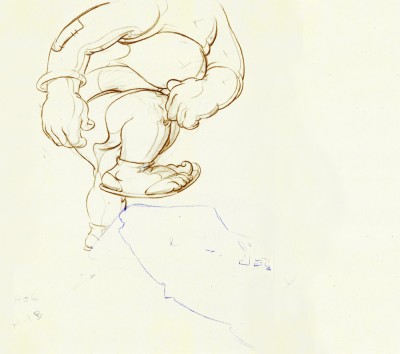

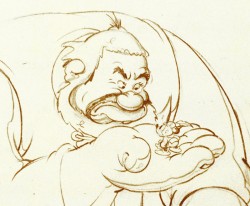

In John Canemaker‘s excellent book, Treasury of Disney Animation Art, there are some beautiful drawings worth looking at. Here they are:

1

1(Click any image to enlarge.)

So let’s take a closer look at some of these drawings.

.

Drawing #3 features this weight shift. As the right foot hits the ground it pronates – twists ever so slightly inward. The hands do just the opposite. The left hand reaches in while the right hand holds back, completely at rest.

It’s a great drawing.

.

.

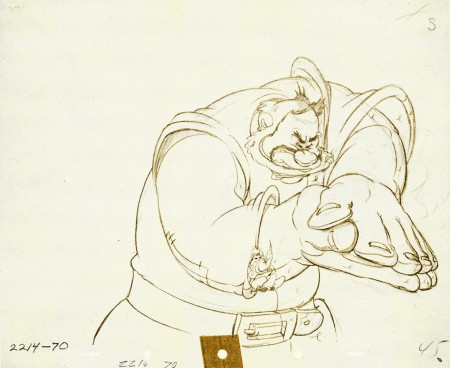

.

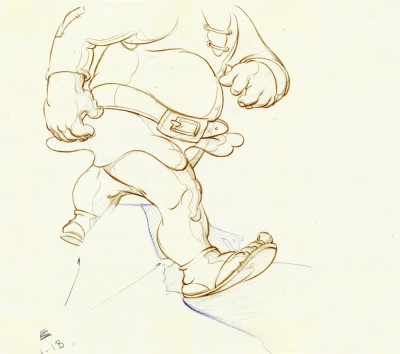

Drawing #4 shows Willie landing on that right foot, and his entire body tilts to the right. The hands twist completely to the left trying to maintain balance. The left foot up in the air is also twisting to the left before it lands twisting to the right.

.

.

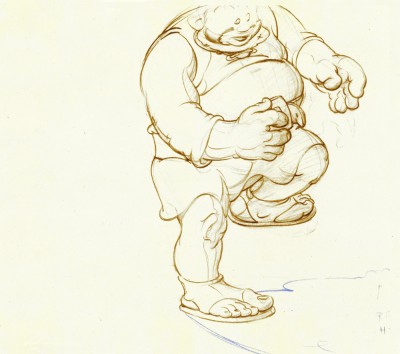

I love how drawing #5 features the two hands flattened out to

make his final stand before sitting down. It’s all about gaining balance.

.

.

.

.

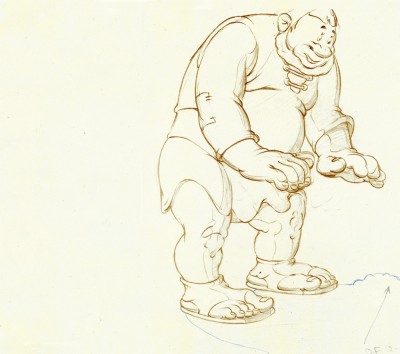

Just take a look at this beautiful head in drawing #6. He’s seated, his head has come forward and tilted forward. The distortion is so beautiful it almost doesn’t look distorted.

What a fabulous artist! This guy just did this naturally.

.

.

.

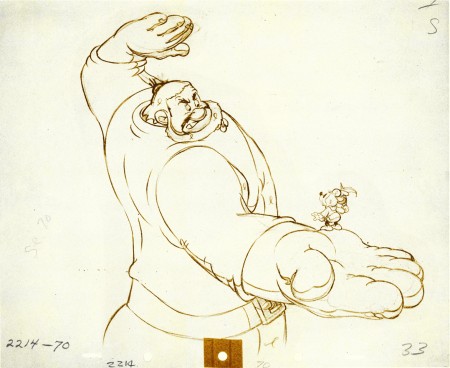

This scene begins with the seated giant eyeing the tiny Mickey Mouse in his hand. The characters are drawn beautifully almost at a rest waiting to get into the scene. The intensity of Willie’s glare is strong, and it’s obvous Mickey is in trouble.

.

Here’s the drawing of the sequence.

Here’s the drawing of the sequence.

The major problem with drawing a giant is his proportion to all the other characters. The screen is more oblong and horizontalal than it is square. (Fortunately, when this film was done it was closer to a square but still not one.) Throughout the film, Tytla had to deal with a BIG Giant and little Mickey. The landscape is also small.

An obvious way of handling it – and one that would be done today, no doubt – would be to force perspective showing it from the ground up – most of the time. In the 30′s and 40′s they stuck to the traditional rule of film and editing, and they would NOT have done this.

Tytla plays with scale as the giant steps over a house and ultimately sits on it.

In this drawing, he does a brilliant drawing forcing the perspective with Mickey in the foreground and Willie’s left hand in the distance. The giant draws into this forceful perspective without calling attention to itself. Today it would be more exaggerated, but Tytla doesn’t want it to be noticed – just felt.

A real bit of art!

Here, Willie moves through that perspective of the last extreme, and he gets larger as he slams his hands to flatten Mickey. To exaggerate that flattening, Willie’s hands flatten for this key drawing. His head flattens as well in grimace.

The giant’s head will move in toward the hands to see the results, and the audience has a front row seat seeing Mickey escape up the giant’s sleeve. There’s a lot going on in this drawing.

.

.

Finally, Willie tries to figure out what’s happened.

The drawing loses most of its distortion and comes to rest.

(Note that there’s still perspective distancing between the two hands.)

Mark Mayerson has done a mosaic breakdown of this cartoon and adds his excellent commentary.

Hans Perk on his site, A Film LA, has just posted the drafts to the earlier Disney short, Giantland. The draft for The Brave Little Tailor was posted a while back on this great site.

Books &Disney 09 Aug 2011 06:44 am

Walt Before Mickey – a book report

- Before I write about the book, let me say that I am truly sad to hear of the death of Corny Cole, one of those great people you meet in the world of animation who seriously changes things for you. I thank Richard Williams for introducing me to him. I’ll try to post a number of his drawings later this week.

- I’ve spent a lot of time in the past two weeks reading a thoroughly enjoyable and inspiring animation book, and I wholeheartedly recommend it to anyone interested in Walt Disney or animation. Walt Before Mickey: Disney’s Early Years 1919-1928 is by Timothy Susanin, and it’s such a real treat that I had a hard time putting down. Yet I wanted to keep it alive, so I brought a bunch of other books in for the ride. I took my time reading it even though taking my time was hard to do.

- I’ve spent a lot of time in the past two weeks reading a thoroughly enjoyable and inspiring animation book, and I wholeheartedly recommend it to anyone interested in Walt Disney or animation. Walt Before Mickey: Disney’s Early Years 1919-1928 is by Timothy Susanin, and it’s such a real treat that I had a hard time putting down. Yet I wanted to keep it alive, so I brought a bunch of other books in for the ride. I took my time reading it even though taking my time was hard to do.

The book tells in elaborate detail (and I do mean elaborate) all of the steps that Disney had taken to get started in this business. The boy who learned how animation could become much more than it was and fought with all the “jack” he had to put it all on the screen. He and Roy, partners in those early days, staked everything on their belief in what they were doing. It’s a great story and makes for something of a page turner.

In J.B. Kaufman and Russell Merritt‘s book, they open with an evaluation of the early period of Disney animation: ” . . . the first striking fact about Disney’s 1920′s films is that they take no particular direction: they don’t evolve, they accumulate.” How accurate an assessment of these films. They don’t get better, they get worse almost as though Disney soon tired of doing them. The gags become repetitive; the characters lose all sense of characterization; even the live-action “Alice” goes from having a large part in the films to flailing her arms so that we can cut back to the drawn animation. This is not the Disney we know from the Thirties & Forties – the one who pushed his people to create the Art form. Essentially, Kaufman and Merritt are looking for the “Art” and give a sharp report on their findings.

This isn’t true of Susanin. His book searches only for the facts and records. But then, let’s look at how the two books were constructed. Susanin’s interviews were limited in comparison to someone like Mike Barrier who did several hundred interviews to write Hollywood Cartoons. He helped Mr. Susanin with many an interview; he also got some help from Kaufman and numerous others in gathering the details and data for the book. Mr. Susanin said, “. . .the Library of Congress, the New York Public Library, MOMA, and the like. I visited the studio when work took me to Burbank, and the Walt Disney Family Museum construction site when work took me to San Francisco. Otherwise, it was lots of virtual work and lots of phone calls with librarians around the country! ”

A lot of the source information came from authors who’d done their own books. Susanin gathered the material – and gathered A LOT OF MATERIAL.

A lot of the source information came from authors who’d done their own books. Susanin gathered the material – and gathered A LOT OF MATERIAL.

The accumulation of the facts is collected in an almost overwhelming fashion by Susanin. Every sentence in the book seems to have some source information backing it up. An almost minute-to-minute account of these early days is gathered and written about. Prior to this book, I found myself guessing at some of the material. I hadn’t really seen all the details until I had them laid out in this book. Add to that details upon details, and you’re breathless from the material presented. (Every person Disney meets seems to have their history displayed. And just read about the Laugh-O-Grams bankruptcy suit in the epilogue.)

Make no mistake about it, this is a period I am wholly and completely intrigued with. I’ve read every book and interview about it that I could find. Kaufman & Merritt’s Walt In Wonderland, Mike Barrier’s The Animated Man, Donald Crafton’s Before Mickey, even Canemaker’s Winsor McCay. I’ve read and read and read again through the material. Yet the way it’s ultimately presnted in this book is so involving. Perhaps it’s all those details I love reading.

In the three week period Walt and Lillian spent in New York looking to sign a second contract to produce the Oswald animation for Universal, you see all the meetings he has taken. All the visits to Universal and Charlie Mintz (who actually contracts the job to Disney and ultimately steals a large part of his staff so that he can dump Disney) and to MGM (Fred Quimby – of all people) and Fox. He spends a lot of time with Jack Alicote the editor of Film Daily who counsels Walt on the business side of the business. You see all the connections; you understand the seriousness of Walt’s situation and you ride with him trying to grasp what straws he has left. It’s hypnotic in all its detail, and it serves as a tight climax in a well written book.

In the three week period Walt and Lillian spent in New York looking to sign a second contract to produce the Oswald animation for Universal, you see all the meetings he has taken. All the visits to Universal and Charlie Mintz (who actually contracts the job to Disney and ultimately steals a large part of his staff so that he can dump Disney) and to MGM (Fred Quimby – of all people) and Fox. He spends a lot of time with Jack Alicote the editor of Film Daily who counsels Walt on the business side of the business. You see all the connections; you understand the seriousness of Walt’s situation and you ride with him trying to grasp what straws he has left. It’s hypnotic in all its detail, and it serves as a tight climax in a well written book.

This segment takes Mr. Susanin 12 pages, full of details, yet it took Mr. Barrier fewer than 2 pages in The Animated Man and fewer in Hollywood Cartoons. It took Kaufman & Merritt in Walt In Wonderland just a bit more than 2 pages to get the information across. It’s not that I needed that additional information to grasp the dire situation Disney was in, it’s that I wanted it. Yet any strong quote in Barrier’s books or Kaufman & Merritt’s has ended up in Susanin’s. It seems that ANY detail that could be found was used to tell the story.

For a geek like me who can’t get enough of this, it’s great. But I wonder about the average reader.

My only real problem with the book is that I wanted the story to go on. At least through Steamboat Willie. Susanin gives a quick sketch of the rest of Disney’s career, but I wanted to get more about that two month period when Plane Crazy was in production. After all, the staff that would leave him – Hugh Harman, Max Maxwell, Mike Marcus, Ham Hamilton and Ray Abrams – stayed on to finish the Oswald pictures while Ubbe Iwerks worked with Les Clark and Johnny Cannon to draw the first Mickey film. A real disappointment set in for me when I came to that epilogue as Disney boarded the train home to start over again.

Yet even in that epilogue there are those delicious details. All of the books personae are laid out with short bios of where they went and when they died. Everyone from Hazel Sewell to Johnny Cannon to Les Clark to Rudy Ising. What a sense of detail. I can tell you I’ll use this book for information for a long time, and there’s not doubt I’ll read it a few more times. This is a wonderful book, and I encourage you to pick it up.

There are some fine interviews with Mr. Susanin on several sites:

- Didier Ghez talks with him on his Disney History site.

- On Imaginerding there’s a nice informal interview.

- Moving Image Archive News also has a review mixed with interview.

Bill Peckmann &Books &Illustration 29 Jul 2011 06:20 am

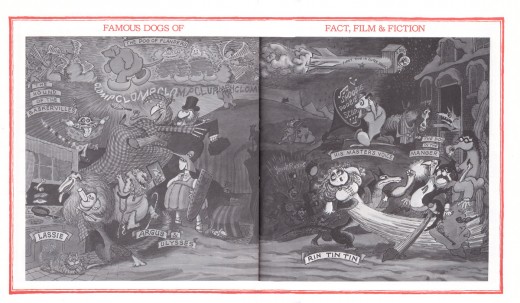

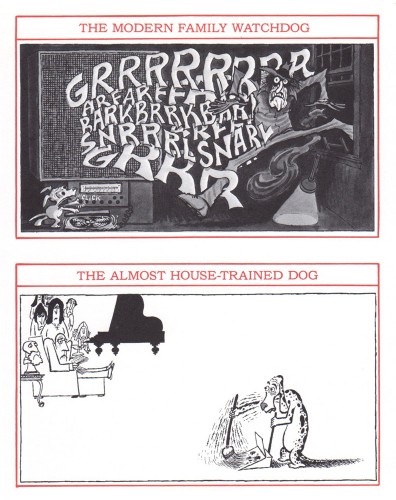

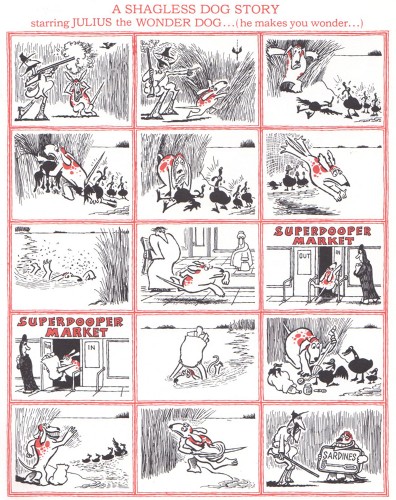

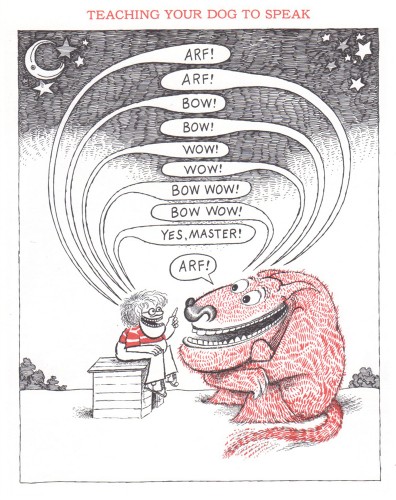

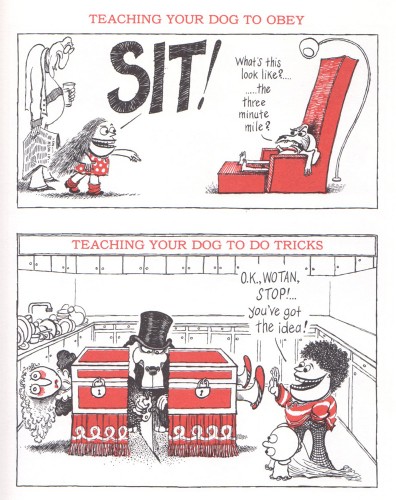

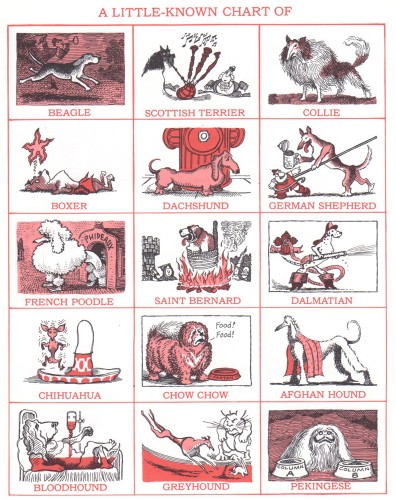

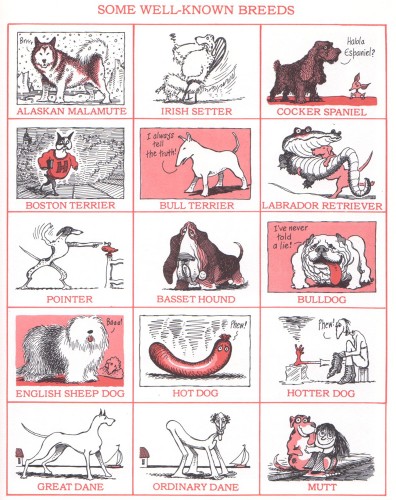

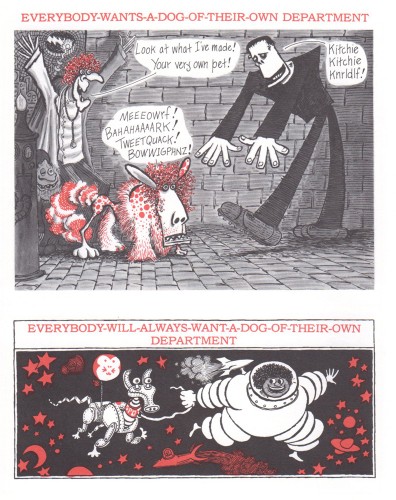

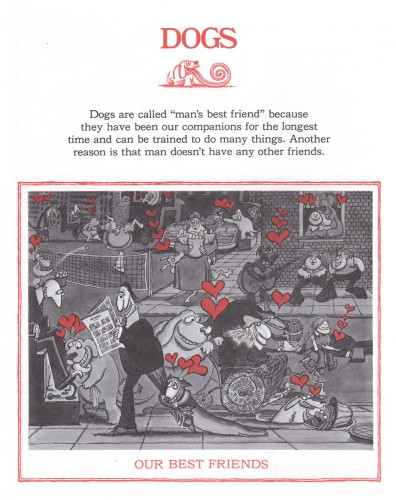

The Dogs of Arnold Roth

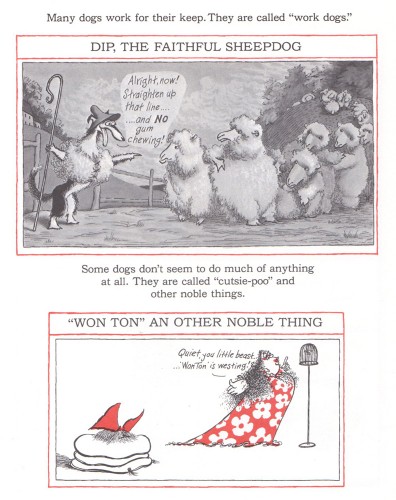

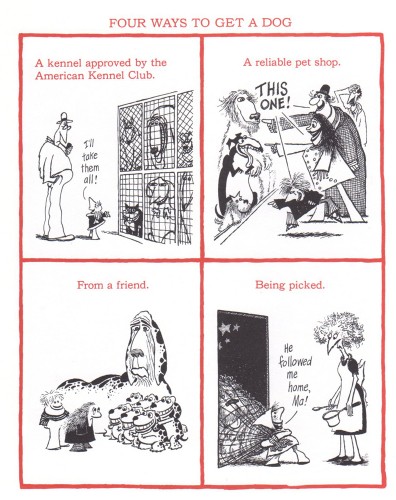

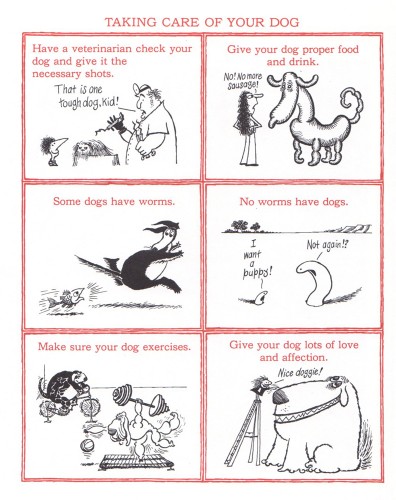

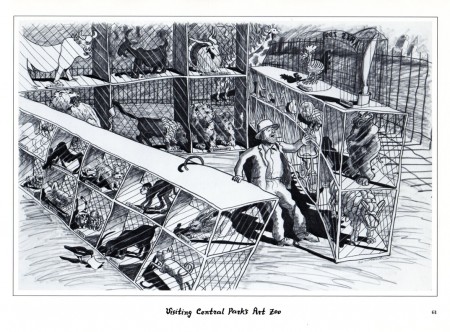

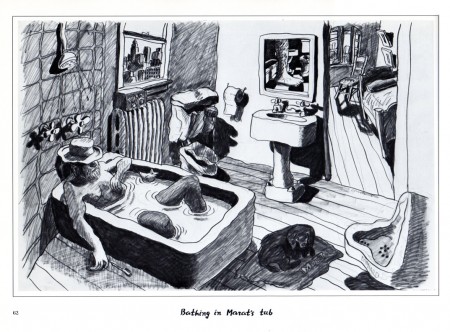

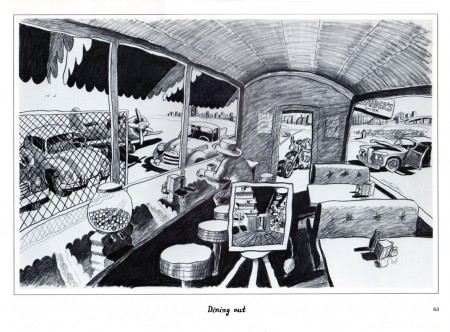

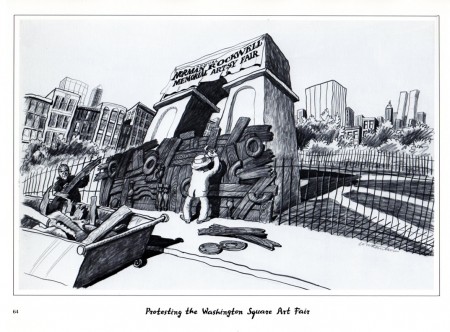

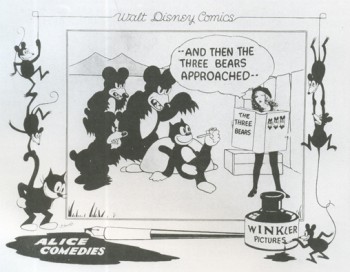

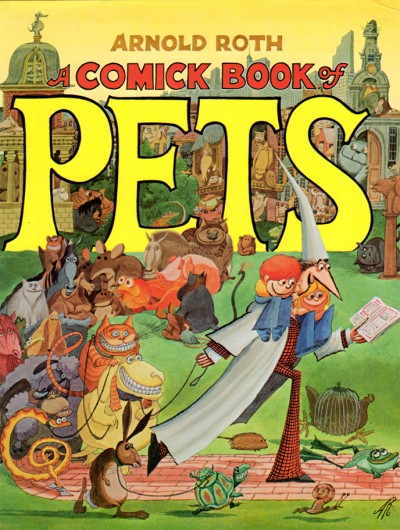

-Previously, I’ve posted a couple of short chapters from the great Arnold Roth book, A Comick Book of Pets.

You can see this chapter on cats posted a couple of weeks ago.

Arnold Roth was born in 1929 in Philadelphia, Pa. He attended public school and was awarded a scholarship to art school. He started free lancing in 1951 and continues to do so. Mr. Roth has had cartoons published in The New Yorker, Time Magazine, Sports Illustrated, Playboy, Punch and the NY Times. He’s worked briefly in animation for John Hubley and Phil Kimmelman. He currently lives in Manhattan with his wife and two sons.

This was sent to me by Bill Peckmann for posting. Many thanks to him for this generous contribution.

1

1

Bill Peckmann &Books &Daily post 22 Jul 2011 06:33 am

Vincent by Constantine – Pt.3

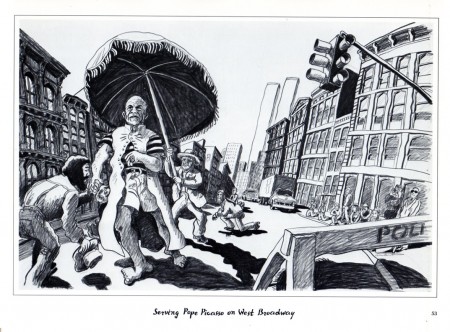

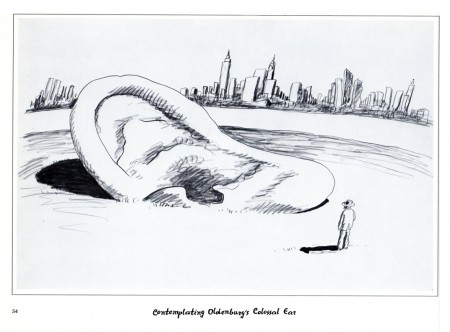

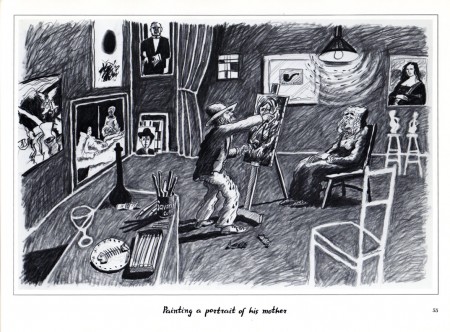

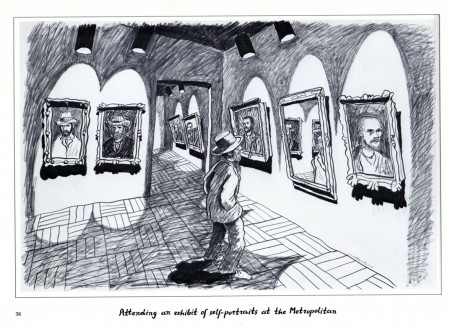

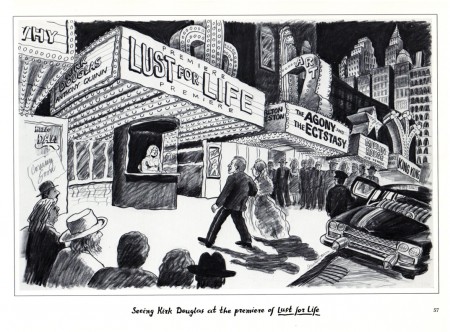

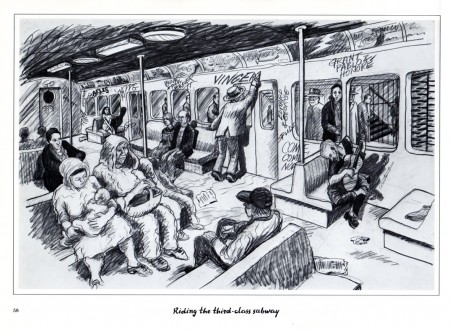

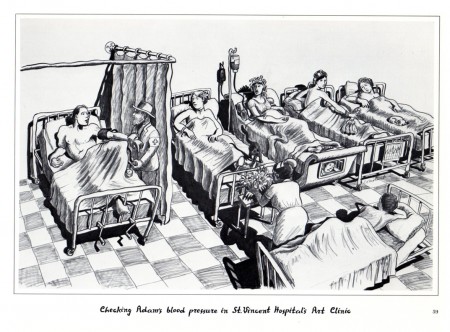

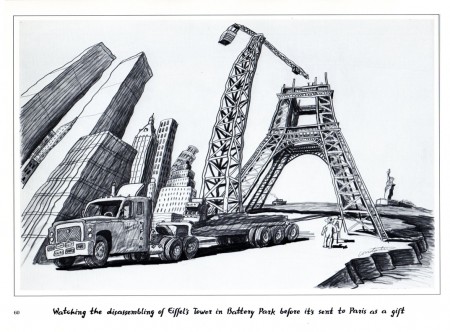

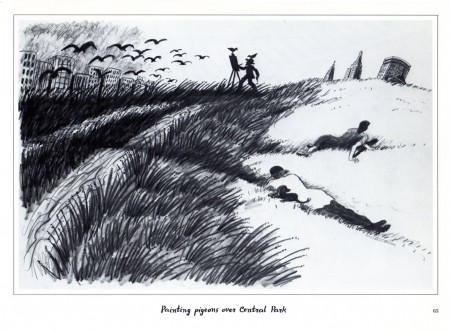

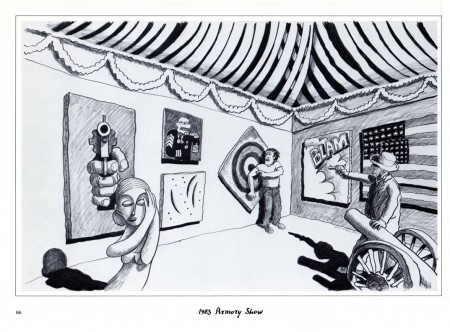

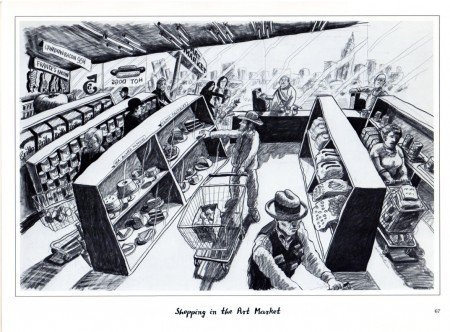

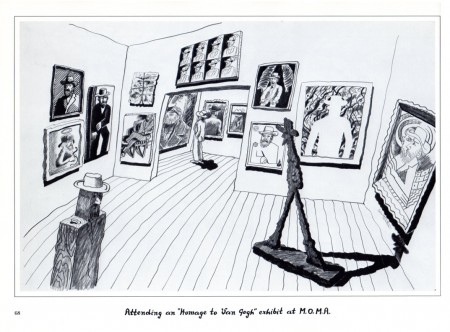

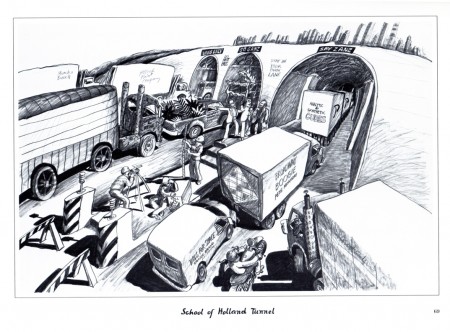

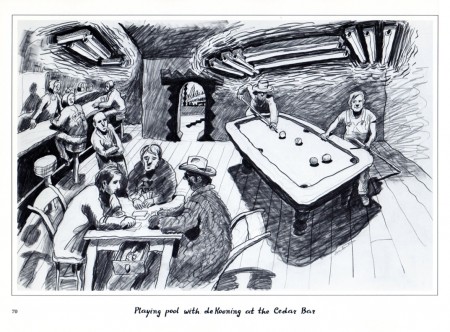

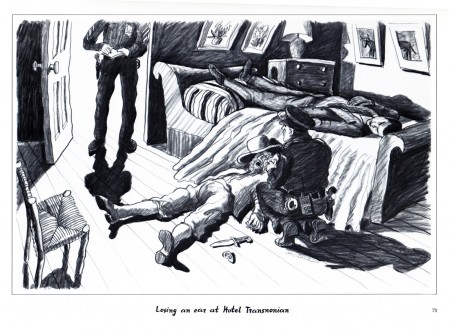

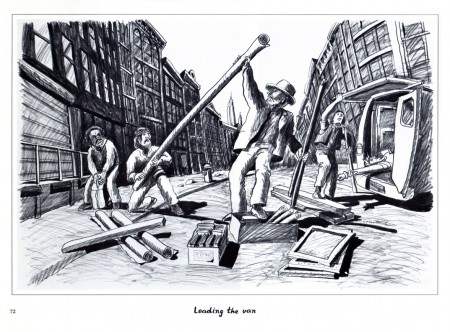

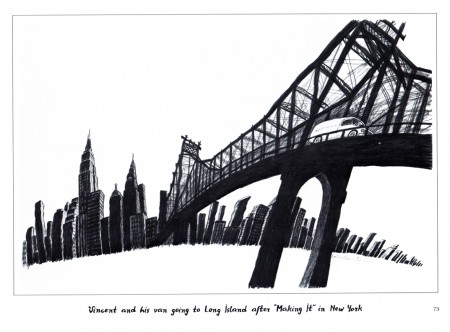

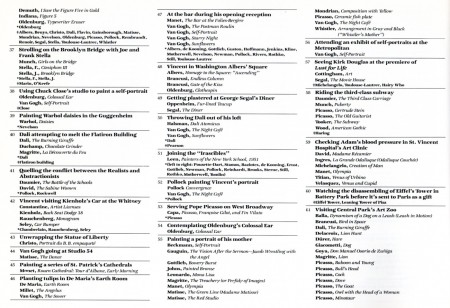

- I recently posted the first two parts of this book by Greg Constantine, Vincent Van Gogh Visits New York. Here is the third and final part of the book.

It was a paperback book Bill Peckmann bought in the ’80s. He introduced me to it and he scanned and sent the material to me. Many thanks to Bill for sharing it with us.

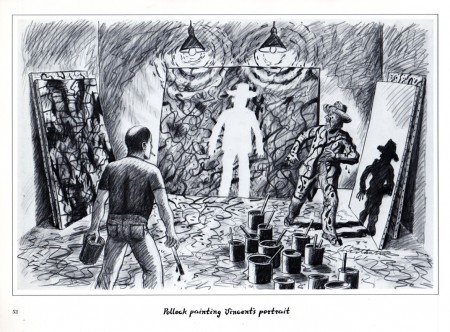

52

52

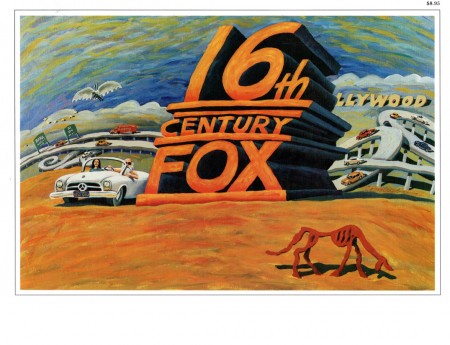

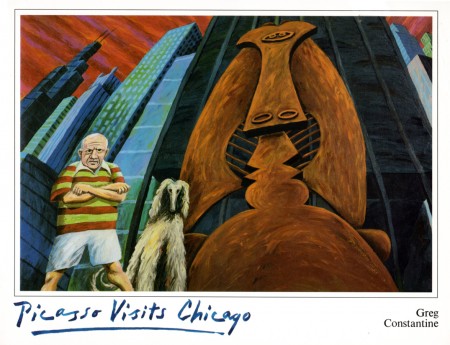

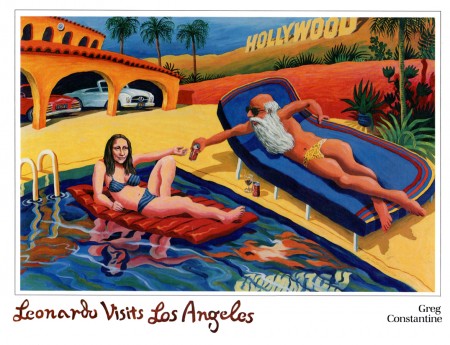

Greg Constantine also has two other books on the market: Leonardo Visits Los Angeles and Picasso in Chicago. Here are the front and rear covers of both books.

Leonardo Visits Los Angeles – front cover

Animation &Books 09 Jul 2011 07:12 am

Tytla, Celestri, Anik and Eric Larsen

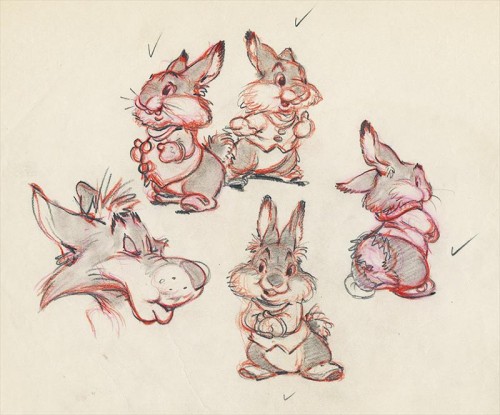

- Mark Sonntag just sent me a model sheet from The Hungry Wolf that he found on auction at Howard Lowery’s. There’s no way to tell if these drawings are by Tytla, but the drawing is beautiful just the same. The inclination to shade in the characters on this film is interesting, though. Many thanks to Mark for sharing.

______________________________

- I am such a fan of Bill Tytla‘s work, I can’t even begin to tell you how much. This week, on his blog, Andreas Deja posted some roughs by Tytla and I couldn’t believe how wonderful some of those drawings are.

- I am such a fan of Bill Tytla‘s work, I can’t even begin to tell you how much. This week, on his blog, Andreas Deja posted some roughs by Tytla and I couldn’t believe how wonderful some of those drawings are.

There’s a series of Grumpy posing in the middle of one of his negative rants, that just sends me. I’ve gone back to the blog at least a dozen times to look at those drawings again and again. The character starts by throwing all of his hostility out to whomever he’s talking to. Then he crosses his arms, with back to the listener. That immediately has him reach out to that person with his entire body, even though his arms stay crossed. It’s such a wonderful mix of emotions so beautifully and graphically presented. All the emotion within Grumpy is out on the floor; he thinks he has nothing to hide and is letting it all out. Thanks to Tytla, we see that Grumpy wants to be like all the others and love Snow White as well. He’s so conflicted and trying so hard not to be honest. This is a brilliant animator at the top of his game.

In the past, I’ve posted quite a few Tytla drawings – most of them loaned to me by John Canemaker. I think in the next week or two I’m going to pull out many of them for a recap. They’re just too great to sit hiding in the morgue of my blog. I want to take another look at them, and maybe share that, again, with you. I hope you’ll indulge my obsession.

- John Celestri is a very good animator who has been a fan of Tytla’s work since I first met him back in 1977 on Raggedy Ann & Andy. John was in the NY Assistant pool that I supervised, and he was a talent to reckon with. Now, John has a new blog that is starting to take shape. It’s like many animator/director blogs in that it’s built around his work in the industry, and there’s a lot of experience for him to draw on. After he left Raggedy Ann, John moved onto Tubby the TUba at NYIT, then Nelvana to work on Rock & Rule. From there he worked on many features in LA, some with Richard Rich‘s studio for Nest Animation. In every step forward, John’s animation kept getting stronger. Now he has his own studio in Kentucky.

- John Celestri is a very good animator who has been a fan of Tytla’s work since I first met him back in 1977 on Raggedy Ann & Andy. John was in the NY Assistant pool that I supervised, and he was a talent to reckon with. Now, John has a new blog that is starting to take shape. It’s like many animator/director blogs in that it’s built around his work in the industry, and there’s a lot of experience for him to draw on. After he left Raggedy Ann, John moved onto Tubby the TUba at NYIT, then Nelvana to work on Rock & Rule. From there he worked on many features in LA, some with Richard Rich‘s studio for Nest Animation. In every step forward, John’s animation kept getting stronger. Now he has his own studio in Kentucky.

The blog, at present, uses John’s own work to show basic animation techniques and script writing problems. It’s growing up into something quite interesting, and I suggest you check it out, if you haven’t already.

By the way, I love that John has pursued a completely non-animation, secondary path in his life. He has also authored quite a few mystery novels with his wife, Cathie. (Their joint site is called CathieJohn.)

- Also worth visiting is the studio site for Dancing Line Productions. This is the animation company of Anik Rosenblum, a Vancouver, Canada animator who brings a lot of grace and lyricism to the animation he’s been doing for some beautiful spots. There are many examples of his work on the site, and you should take a look at some of it.

Below is an animated piece called “The Autumnal Walk” which gives a good idea of Anik’s work.

The Autumnal Walk

This is one of my favorite pages of Dancing Line’s site. It answers the question, “Why hire us?” Anik has a good, sweet sense of humor. More power to him; I hope his company is successful.

- I just read an interview with Eric Larsen in Don Peri‘s book, Working with Walt. Something Eric said caught me and I thought it would be good to quote him:

- When I came into this business, Frank [Thomas] and Ollie [Johnston] and Marc Davis and Ward Kimball and John Lounsbery all came about the same time. Hal King and a few more came then, too. There was a group of us who developed, and Walt started putting a certain’ amount of responsibility on us in a way. But we came through what we called me unit system: each one of us came up through a very strong animator. These are the men I spoke of a little while ago when I said that here were such great talents and yet they opened up their arms to you to let you have everything they had: Ham Luske, Norm Ferguson, Bill Roberts, Wilfred Jackson, Ben Sharpsteen, Freddy Moore, and then just a little bit later Bill Tytla. Good gosh, what more could you ask for! We came up under those men, being taught, you might say, with them looking over our shoulders. A number of years ago, we dissolved the unit system. Don’t ask me why because I can’t answer. It’s the biggest mistake we made. Now we are trying to set up units again. Like on Bambi, I had ten animators plus all their assistants

working with me. I spent most of my time up here in this room and then would go down and animate at night. But you could keep control of certain things. You learn by working with somebody who has gone I tough the mill. But you’re always learning. There’s no such thing as I graduation in an animation class.

Basically, Eric Larsen is saying that only by our working together can we advance the art of Animation. That’s true. But I wonder if we do that anymore. I wonder if we’re open to each other to try to help out. I hope so. I hope all these new sites, such as John Celestri’s site, help to impart some tidbit of knowledge to someone coming up. It’d be great if it does.

Bill Peckmann &Books &Illustration 01 Jul 2011 07:28 am

Mad Mad World – 2

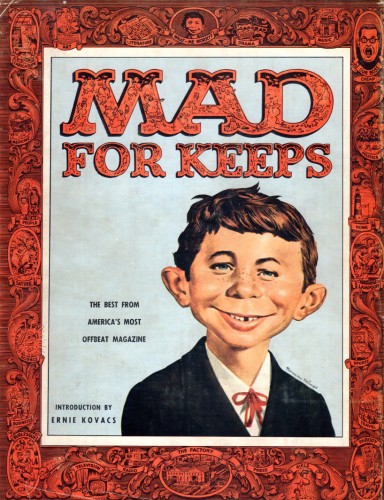

- In a second posting of art reprinted from MAD Magazine, Bill Peckmann forwarded the following covers and the two stories that follow. I’ll let Bill’s words introduce the material. The material comes from the collected Mad For Keeps.

1

1Here is the cover, comprised from one of the issues,

which has Harvey’s great MAD logo, Bill Elder’s border and probably

Norman Mingo’s first Alfred E. Neuman illustration.

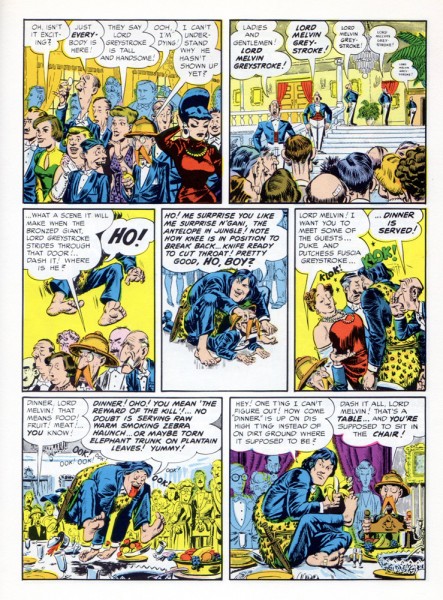

These are the only two stories from the MAD comic books in the book that are reprinted in color. (And good color it is because of the hard cover production.) Again, the talent of Harvey Kurtzman really shines through with his writing and laying out of the pages. They are also great examples of Harvey the editor choosing the right cartoon talent to complete the job.

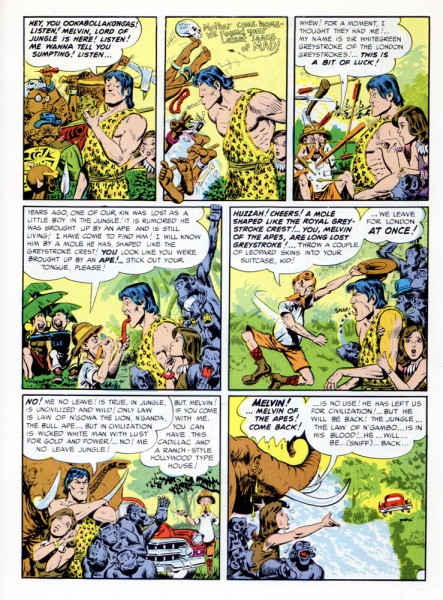

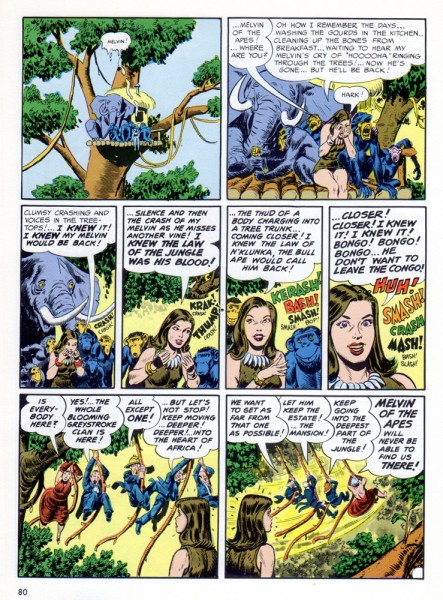

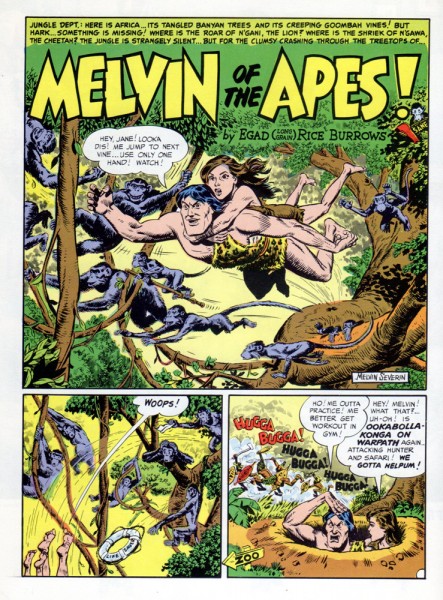

The first story “Melvin of the Apes”, is drawn by John Severin, he certainly captures the flavor of the early Hal Foster Tarzan strip.

1

1

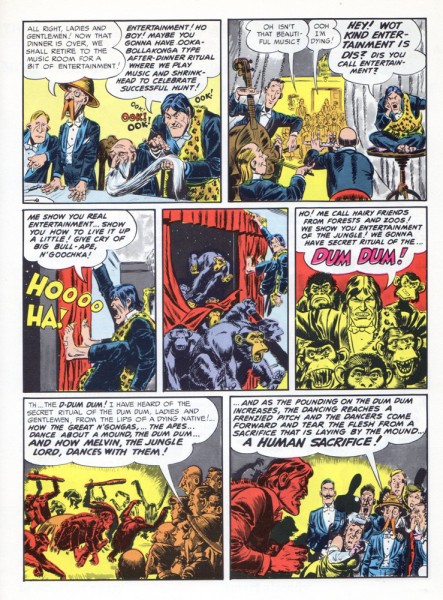

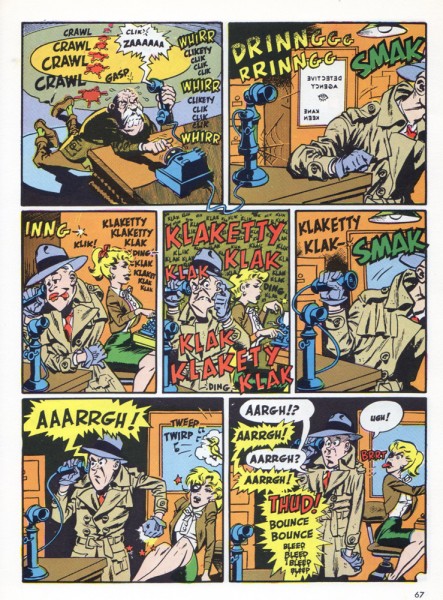

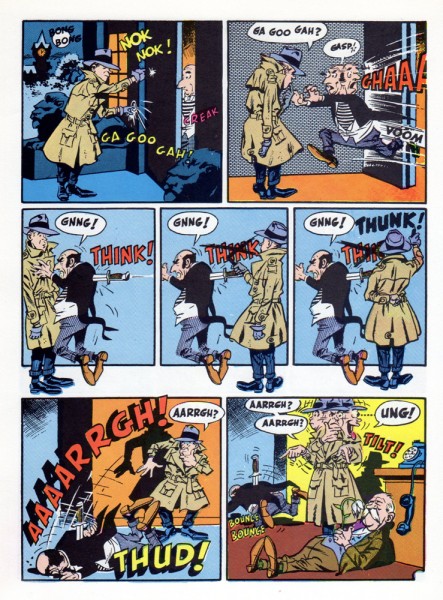

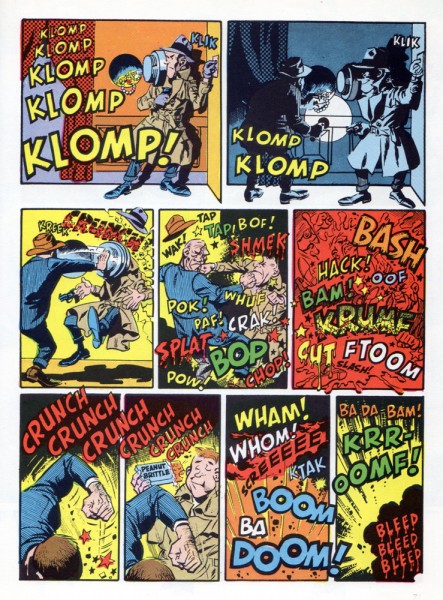

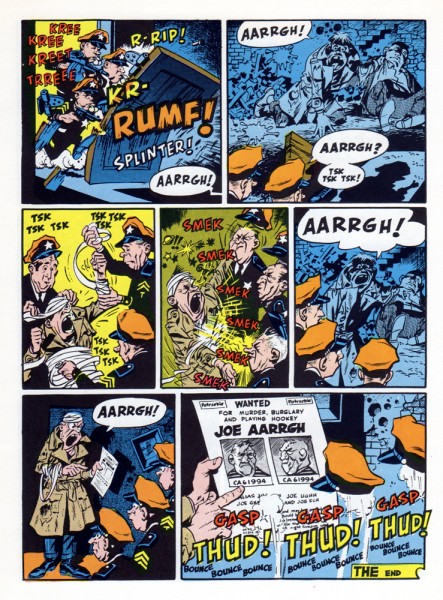

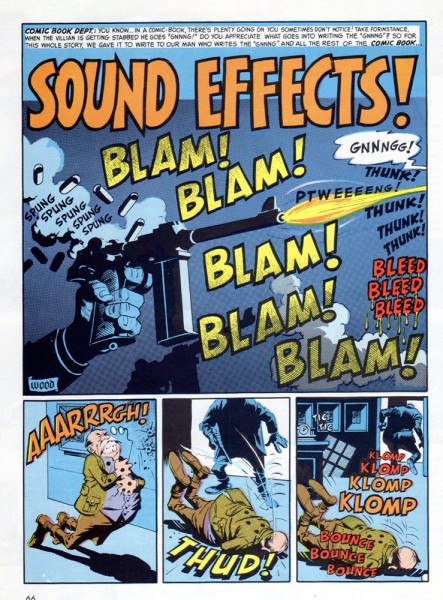

Here is the second story, it’s with cartoonist Wally Wood. IMHO, it’s one the stories where their collaborative powers are at their zenith. The animated continuity is so good, It’s hard to picture this story without either talent or being done by somebody else.

1

1

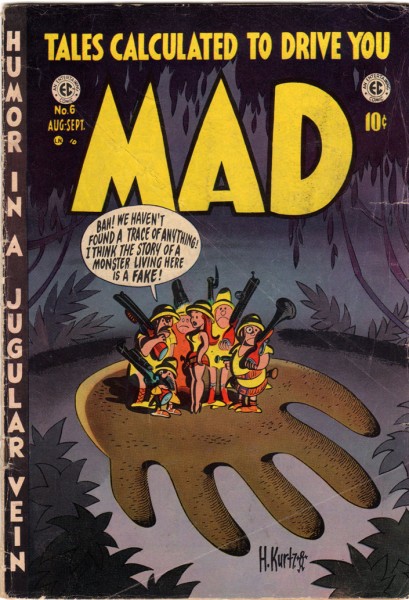

Here are the three faces of MAD. The first cover is of MAD comic book # 6, (1953) drawn by Harvey for the inside “King Kong” story spoof. This is the issue that contained “Melvin of the Apes”.

1

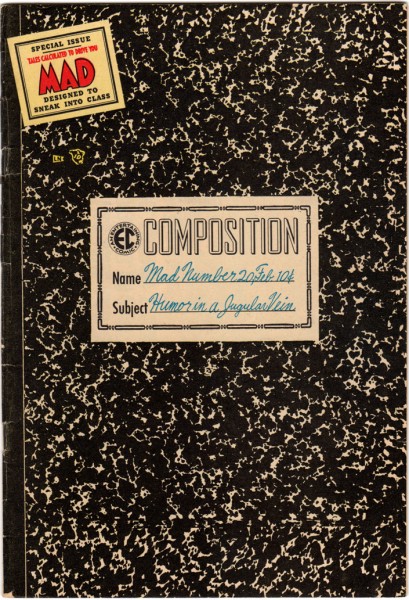

1 This is the cover from # 20 (1955), by now Harvey had been spoofing “covers” (magazines, newspapers etc.) for about ten issues. This is the issue that contained “Sound Effects!”

2

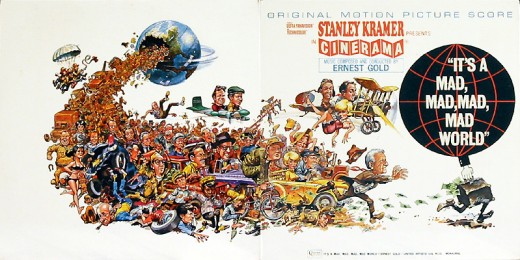

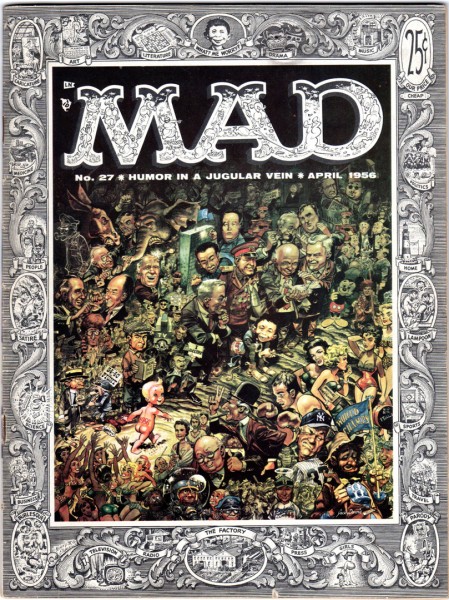

2This is MAD magazine cover # 27 (1956). It is the fourth magazine cover done and the first Jack Davis cover. It’s easy to see the “It’s A Mad Mad Mad Mad World” (1963) movie poster lurking in there and also a lot of TV GUIDE covers to come.

(Side notes: As high school students, we cut class one day in 1958 to visit the offices of MAD on Lafayette St. and were so fortunate to see the original of this cover hanging on the office wall. The reproduction does not do it justice at all! I was also lucky enough to be at Elektra Films in ’63 when they shot a trailer for “Mad Mad Mad Mad World” using Jack’s original poster art. Jack’s originals have got to be seen to be believed.)

3

3Here’s the record jacket (front & back) for It’s A Mad Mad Mad Mad World.

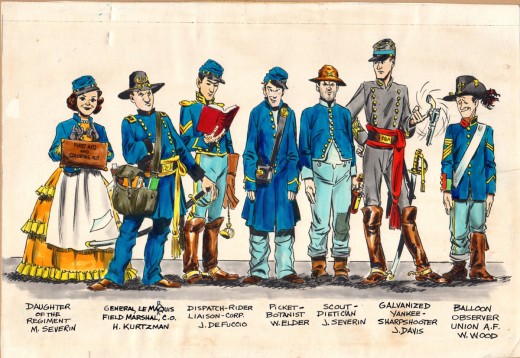

Finally, this is the Kurtzman war comics crew as seen by John Severin. It was done sometime in the early ’50′s. John’s love for drawing historically accurate comic book stories really comes through here.

There are some great Basil Woolverton comic strips at John Glenn Taylor‘s blog