Category ArchiveAnimation

Animation &Commentary &Independent Animation 22 Apr 2010 07:30 am

Toe Tactic & Howdy Doody

- I’m a bit late in reporting this, but I just found Emily Hubley‘s excellent feature, The Toe Tactic, on the Sundance Channel. I’ve reviewed the film in that past and have shared some of my thoughts. Here’s my review of the DVD.

Written and directed by Emily Hubley.

Voices of: David Cross, Andrea Martin,

Eli Wallach, Marian Seldes, Don Byron

Animation by Jeremiah Dickey and Emily Hubley.

The show can be seen on these dates and times in April. Record it if you can’t watch it live.

April 21 4:10am

April 25 10:00pm

April 26 3:55am

April 26 11:45am

- One of the more amazing posts I’ve seen on line in recent weeks (maybe I should say months) is Cartoon Brew TV’s >Howdy Doody and His Magic Hat. This UPA film by Gene Deitch seemed to be lost until Jerry Beck and Amid Amidi were able to discover a good quality print that they’ve put on line.

The piece has to be seen as an edxcellent bit of historical discovery. Deitch’s direction is first rate given the obviously meagre budget. Cliff Roberts’ color design is first rate (given the slight color deterioration of the print) and offers a rich original bit of life. Duane Crowther‘s animation is limited to the point where it might be called more of an animatic than an animation, but even that is done in a spirited sense of fun.

The real find for me was the brilliant score by Serge Hovey. I don’t know his work, but I’m certainly going to be searching to find out more about this composer. The score threads it all together and the playful way that Crowther animated off the score indicates that it was probably prerecorded.

I’m pleased to see this film has been found (thanks, apparently to the work of Dave Gibson for finding the film at the Library of Congress, and to OndÅ™ej MuÅ¡ka for the restoration work on the print.) This is not the greatest film ever made, nor even one of the best UPA shorts. However, it was a missing artifact in the career of a key director in animation’s history. It’s also an absolutely original looking piece that stands above many of the average films of today.

This film is just the tip of the iceburg from the guys at Cartoon Brew. When they’re on it, they’re on it. They share information before anyone else gets the news; they share historical films (such as Howdy Doody and another post of Flebus from Ernie Pintoff while at Terrytoons – posted to memorialize the passing of Allan Swift, the NY mega voice artist), and they present new works we might otherwise miss.

But at this point, everyone in animation knows that this is the first site to visit when sparking up the computer.

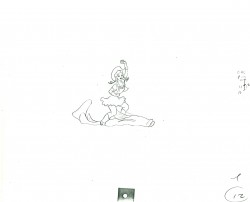

Animation &Independent Animation &Tissa David &walk cycle 21 Apr 2010 09:20 am

Tissa’s Old Lady

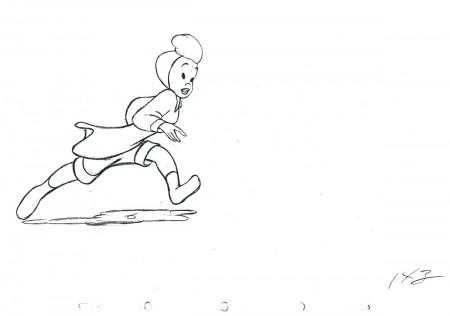

- Here’s a walk cycle Tissa David animated for R.O.Blechman‘s hour program, A Soldier’s Tale. This is a tiny scene in the show. The camera is moving in on her, so I tried to adjust her a bit to be able to view this as a cycle.

For a slightly overhead view, wth her walking in 3/4 profile, it’s pretty complex animation. The woman carries a lot of weight in her body, and I think Tissa did a great job with her.

1

1  2

2

The following QT represents the drawings above exposed on two’s.

Click left side of the black bar to play.Right side to watch single frame.

Animation &Articles on Animation &Independent Animation 20 Apr 2010 08:05 am

The Picture Book Animated

I just caught up with Cartoon Brew‘s posting of the Gene Deitch directed UPA short, Howdy Doody and His Magic Hat. I’ll have a lot to write about this film soon, however I wanted to add this piece by Mr. Deitch.

Gene Deitch wrote the following article which initially appeared in The HORN BOOK, in 1978; then was reprinted in Animafilm #5, 1980. I post it again for your benefit.

The Picture Book Animated

by Gene Deitch

Living in Prague, an ancient town so full of its own stories, I am surrounded by an instructive ambience for my kind of work: making films from books. Building Prague took a long time; every period of European architecture is represented in the city. Each era adopted the building style which conformed to the artistic expression of that particular time – Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, baroque, rococco, art nouveau, cubist, prefab. Just seeing all this every day helps me to take the long view and to take my time. Right outside my window, a Gothic tower stands in the courtyard. In the sixteenth century an alchemist worked there trying to change lead into gold. Now I’m here trying to avoid doing the opposite, for I start with gold. Morton Schindel of Weston Woods always sends me the very best books he can get his hands on. My job is to shine them onto a movie screen, trying to keep the image bright and the focus sharp.

Living in Prague, an ancient town so full of its own stories, I am surrounded by an instructive ambience for my kind of work: making films from books. Building Prague took a long time; every period of European architecture is represented in the city. Each era adopted the building style which conformed to the artistic expression of that particular time – Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, baroque, rococco, art nouveau, cubist, prefab. Just seeing all this every day helps me to take the long view and to take my time. Right outside my window, a Gothic tower stands in the courtyard. In the sixteenth century an alchemist worked there trying to change lead into gold. Now I’m here trying to avoid doing the opposite, for I start with gold. Morton Schindel of Weston Woods always sends me the very best books he can get his hands on. My job is to shine them onto a movie screen, trying to keep the image bright and the focus sharp.

My films exist only in their relationship to the books from which they have been adapted. The goal of these films is to reinforce the child’s interest in the original book. I share Mort Schindel ‘s belief that books are still the best medium for storytelling and for the preservation of literature — a medium which is always at hand. Our aim is to illuminate each book so that a child will find his way back to it. Among my attempts to transmute gold into more gold, or at least into quicksilver, are film adaptations of “The Happy Owls” (Atheneum), “Rossie’s Walk” (Macmillan), “The Three Robbers” (Atheneum), “The Swineherd”, and “Strega Nona” (Prentice).

Like the successive architects of Prague, I resort to a medium of expression of my own time – the motion picture. Ed and Barbara Emberley’s “Drummer Hoff” (Prentice) is an example of what I mean. Hidden among the bright colours of the outwardly lighthearted book are some interesting clues to its real depth. As the grandly uniformed soldiers strut along, intent on assembling their technological triumph – an elaborate cannon – they don’t seem to notice the flowers underfoot or their tiny observers, the birds, and the soldiers actually stepping on the flowers and shooing away the birds and thus to emphasize the meaning of the last page of the book – and of the final shot in the film – nature winning out over man and his destructive machines. Now, I don’t expect that children will absorb all of these ideas and details as such, but I do expect that when they pick up the book again (maybe because the film has now made it special for them), they will notice some things they might not have been aware of before. My hope is that they will love the book more for having seen the film.

Like the successive architects of Prague, I resort to a medium of expression of my own time – the motion picture. Ed and Barbara Emberley’s “Drummer Hoff” (Prentice) is an example of what I mean. Hidden among the bright colours of the outwardly lighthearted book are some interesting clues to its real depth. As the grandly uniformed soldiers strut along, intent on assembling their technological triumph – an elaborate cannon – they don’t seem to notice the flowers underfoot or their tiny observers, the birds, and the soldiers actually stepping on the flowers and shooing away the birds and thus to emphasize the meaning of the last page of the book – and of the final shot in the film – nature winning out over man and his destructive machines. Now, I don’t expect that children will absorb all of these ideas and details as such, but I do expect that when they pick up the book again (maybe because the film has now made it special for them), they will notice some things they might not have been aware of before. My hope is that they will love the book more for having seen the film.

Tomi Ungerer’s almost-over-the-edge book, “The Best of Monsieur Racine” (Farrar), is also loaded with lurking symbols, which might unnerve a children’s librarian. Tomi believes in there is much more to the book, and I tried to bring out something loving and charming that I found amidst the crazy tangle of startling images. What caught me was Monsieur Racine’s perfect serenity in his world of chaos. I felt he had just the kind of insulation which children have – carrying on and doing his own thing, immune to all of the crudity going on all around him. He has retained a childlike purity of concentration. His relationship with the beast, even when it was revealed to have been based on a gross deception, survives and continues, merely revised and adjusted to the new circumstances. This is marvellous, and I hope that the film will enrich the child’s comprehension of the book.

The greater the book, the greater our responsibility – and hazard. It may impress or dismay you that we worked on Maurice Sendak’s “Where the Wild Things Are” (Harper) “on and off and in and out” for five years before we had a film. “Wild Things” is the Mount Everest of picture books, and we had to film it simply because it was there. Once undertaken, there was no hedging. A film version would have to make specific what might be imagined in many different ways. This, incidentally, is the major risk a film-maker faces in adapting a work from another medium. There is never any one right way, but it is still necessary to have a conception and to follow it through. Maurice himself knew there was no point in making a film adaptation at all unless we could use the motion picture medium to extend some of the subtle implications of the book. He came to see me in Prague in 1969, and we had some long walks through old and dark corners of the town. We both wanted a magical film, and he left me some fascinating hints to work with: “In this story everything is Max… As for the music, think of “Deep Purple”.

Well, the old song “Deep Purple” stirred memories for me, too. Like Maurice, I was a child of the thirties. I began to see the roots of musical and sound devices which might suggest the distance between Max and his parents, who ware probably also children of the thirties. After all, why is Max “making mischief of his parents”. But where are they? Unseen in the book, I imagined they were probably in the next room having a party or (in today’s terms) watching TV. Anyway, they were not with Max. So I came to the notion of using that muffled, bland music of the 1930s, the sound of applause, the snatch of a TV comic’s joke (which just happens to be cogent), and so on. The music itself expressed the distance between Max and his parents, and with progressive distortion it could also express Max’s growing rage and journey into fantasy.

I wanted all of the sounds to be within Max’s home experience. So to create the “Wild Things” dance rhythm, I restricted myself to domestic sounds, specifically those which might express Max’s feeling of isolation: a gas oven lighting (Mother too busy for Max); a door slam (he was shut in or out); a car starting (Father going off to work); a baby crying (competition). All of these sounds repeated over and over on a tape loop, were used to heat up the music, which I made weird simply by spinning the record with my finger and letting the sound reverberate in my tape recorders.

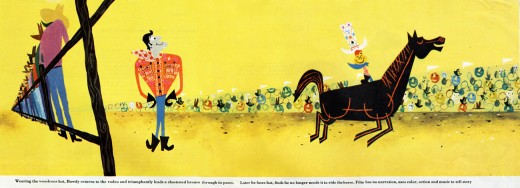

Viewing any of our films should also indicate that we strive always fot the result of “the picture book projected”. We go to such great lengths to capture the graphic look of each book that viewers might assume they are seeing the actual book on the screen. In fact, though, we have never used any of the book illustrations. The technical processes of our medium require that we re-create every drawing and painting in terms of motion and film-frame composition, and a film’s wider scope often calls for scenes or additional artwork not found in the book at all. We must actually absorb the artists’ own styles in redeveloping the drawings and paintings specifically for film. In an effort to achieve absolute fidelity, we even asked Quentin Blake to send us the actual colored crayons he used for his illustrations for “Patrick” (Walck), and we used what was left of the same crayons to do our film backgrounds.

Some books are almost scenarios for films and need virtually no adaptation; Crockett Johnson’s “Harold” series (Harper) is the perfect example. The books are so masterfully constructed that one might easily dismiss their perfection as mere simplicity. As I undertook “A Picture for Harold’s Room” and “Harold’s Fairy Tale”, Johnson warned me, “Don’t be fool by the seemingly simple!” He was right. These films were devilishly difficult to make. “Harold’s Room”, for instance, is a fascinating lesson in size relationships and perspective. To make it work on the screen, Harold had to be exactly the same size in relation to the film frame as he was to the pages of the book. Consequently, we could allow ourselves no close-up cuts nor camera moves in or out. In effect, the entire film must appear to be one continuous scene – all from the same camera position and all on a plain, smooth background tone, where no mistakes could be hidden. Any mistake at all meant that we had to start shooting all over again “from the top”.

Some books are almost scenarios for films and need virtually no adaptation; Crockett Johnson’s “Harold” series (Harper) is the perfect example. The books are so masterfully constructed that one might easily dismiss their perfection as mere simplicity. As I undertook “A Picture for Harold’s Room” and “Harold’s Fairy Tale”, Johnson warned me, “Don’t be fool by the seemingly simple!” He was right. These films were devilishly difficult to make. “Harold’s Room”, for instance, is a fascinating lesson in size relationships and perspective. To make it work on the screen, Harold had to be exactly the same size in relation to the film frame as he was to the pages of the book. Consequently, we could allow ourselves no close-up cuts nor camera moves in or out. In effect, the entire film must appear to be one continuous scene – all from the same camera position and all on a plain, smooth background tone, where no mistakes could be hidden. Any mistake at all meant that we had to start shooting all over again “from the top”.

If you would take apart a copy of “A Picture for Harold’s Room” and paste the pages together, you would see that it is based on one large drawing, which Crockett Johnson obviously worked out in advance. Of course, we had to do exactly the same thing. We made a huge drawing of Harold’s landscape and manoeuvered it under our animation camera. For the pencil layout of this we had already prepared seventy-five hundred inked and painted drawings of Harold himself following the lines of the overall landscape. As we placed these drawings over the landscape one by in reverse order, we wiped away our background painting to match each position in his room and working our way relentlessly back to the little town. Thus, beneath our camera Harold undrew his scenery. When we finished shooting, the big drawing had been completely wiped out; and only when the film was projected forward did it reappear.

Most people realize that it takes hundreds, even thousands, of drawings, representing carefully calculated phases of each action, to give the effect of animation in even the shortest film. A glance at the illustrations of “Where the Wild Things Are” indicates the formidable task. As a matter of fact, “Wild Things” required a totally new of rendering characters onto our animation cels* and a totally new way of making them move. When Maurice Sendak said of the story, “Everything is Max”, he has hoping I could find a way to show that the Wild Things were actually a fantasy expression of Max’s own mind, a projection if his anger. Maurice further envisioned them as having “slow, heavy, dream-like movements” and as being “clumsy, dumb, sluggish, heacingcreatures… not horrible”.

To produce this effect on film, and to do it in a way that would make clear the “Wild Things” status as evanescent fragments of Max’s imagination, I devised a way of photographing the phased drawings in an interweaving series of dissolves. This device, in combination with the slowed-down, wavering music and special effects, was part of our attempt to fulfill Maurice’s extravagant wish for us to “go beyond the book”. (I was later thrilled with his equally extravagant praise of the sound track.) Going “beyond the book” refers simply to the nature of the film medium and not to extending the book’s content or meaning. We endeavour only to bring out what is there or what we feel is there. “The Horn Book” review of the film concisely stated what we attempt: “recasting of one aesthetic form into another.”

This is the problematic task with every book we film. Each book has set me off in a new direction, prodding me to find a new way, a specific solution to the problem of adapting that particular book to the motion picture medium. I have no formulas. My private conceit is that without my name on them, no one could tell that all these films came from the same director. For me, my Oscar-winning cartoon “Munro” was a success when people asked if it was made by Jules Feiffer himself.

I used the word problematic. Is our work valid? The question haunts me. Why should we try to make films of picture books? Why shouldn’t the books be left to communicate in their own way? Why don’t we concentrate on developing original film stories? we do this, too, of course. I made “The Giants”, my own films, a child sees that books do have life, that they have movement and sound. We try always to leave room for the child to participate with his own imagination.

For instance, the ending of “Leopold the See-Through Crumbpicker” leads directly to the idea that the children can draw and paint their own variations for decorating the invisible cookie-eater. In “Changes, Changes” I added a box of building blocks, not actually shown in the book, thus inciting children to carry one the story, stacking up their own changes. The film “Patrick” ends just as the colourful procession heads back toward the drab village seen at the start of the film. By this time the children know what will happen there when Patrick and his full-colour fiddle arrive; but they don’t see it, so they are allowed to imagine the ensuing scene for themselves.

Patrick’s fiddle, incidentally, plays virtuoso variations on Dvorak. In “A Picture for Harold’s Room” the purple crayon draws to the music of a classical string quartet. Unadulterated Janecek, in all its Slavic richness, precedes the musical frame for “Zlateh the Goat”. Our version of Andersen’s “The Ugly Duckling” introduces children to Carl Maria von Weber. For our original scores we have gone to many lengths to provide just the right music. We needed authentic Central African music for “A Story”. My Czech wife Zdenka, who is also the production manager for our films, found antique instruments in a half-hidden ethnographic museum here as well as a curator-musician who could instruct us. A curious interplay of cultures resulted in our recording ses-ion: genuine African instruments played by Czechs, along with a recording by an African story-teller reading from a book by an American woman – for a movie for Western children being made in an eastern European studio.

The existence of our film versions, I am told, have often helped a book stay in print and increase in sales. Films are powerful but transitory, seen and suddenly gone. The book can always be read and will be even more after a child has seen it on the screen. The permanence of the printed word, however, is now being challenged. Movies, audiovisual media, and especially TV are very powerful forces. But must they destroy book reading, or can they complement it? The flood cannot be dammed, but it might be directed. We are trying to provide a channel which flows toward books rather than away from them.

*In animation production, moving figures are usually rendered onto transparent “cels”, sheets of acetate film, so that the stationary background painting can be photographed simultaneously on each film frame.

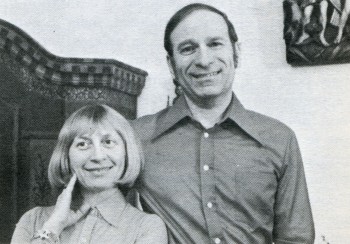

GENE DEITCH – American director living and making films (in his own studio) in Prague. During thirty four years he has directed more than thousand films and commercials and received numerous awards including the Oscar for “MUNRO” in 1959. Specializing in the adaptation of children books.

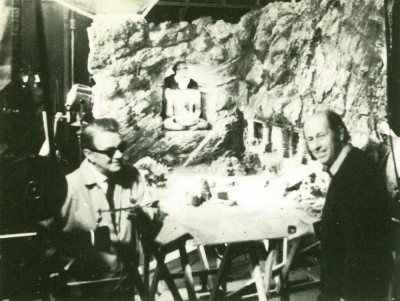

1. Gene Deitch with his Wife

2. Strega Nona

3. Smile for Auntie

Animation &Disney 19 Apr 2010 10:17 am

All the Cats

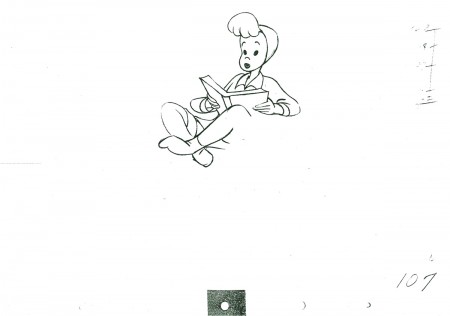

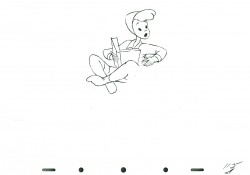

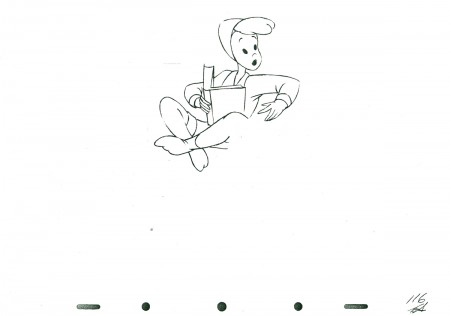

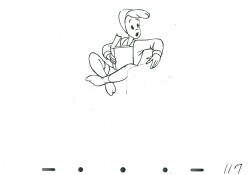

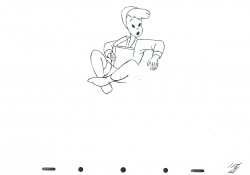

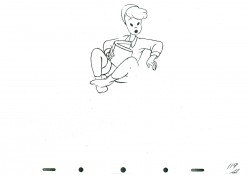

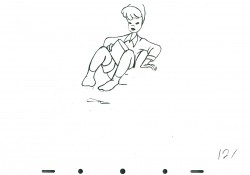

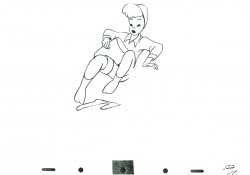

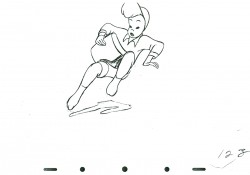

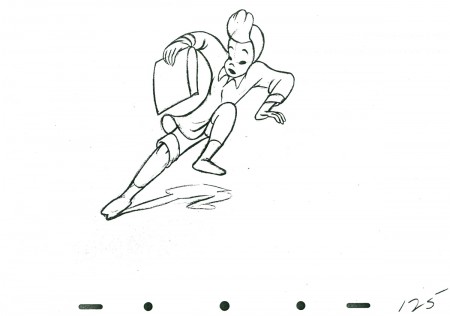

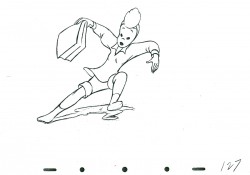

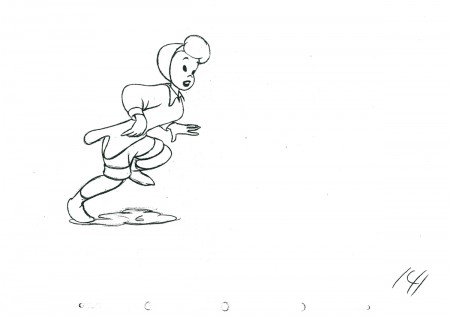

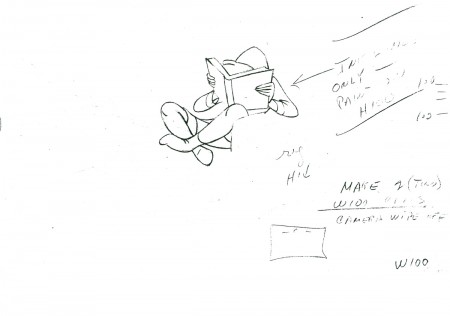

The following is the first half of the first of several connecting scenes I have which were animated by Ollie Johnston for All the Cats Join In. It’s not my favorite film, and Ollie, though a masterful animator is not my favorite.

I’ll post the second half of this next week.

100

100

The following QT movie represents the drawings for the

enitre scene – this includes those from Part 2.

It’s exposed as per the drawing numbers would indicate.

Right side to watch single frame.

Many thanks for the loan of this scene by Lou Scarborough.

Animation &Articles on Animation &Independent Animation &Puppet Animation 14 Apr 2010 07:41 am

Teddy Shepard interview

- Dipping back in the well of the Closeup Magazine from 1976. Edited by David Prestone, this magazine featured articles – mostly interviews – with 3D stop-motion animators. The focus of this particlar issue was Michael Myerberg‘s Hansel and Gretel, an animated puppet feature done in 1954.

Teddy Shepard

Born in New York, Ms. Shepard became a drama major in college, and appeared in several summer stock and off-Broadway productions. It was while making the rounds of theatrical agencies in search of work that she became aware of the interviews Michael Myerberg Productions was conducting for animators. After working on HANSEL AND GRETEL, she spent some time with the Suzari marionettes, graduating to the HOWDY DOODY television show (where she originated the character of Dilly-Dally, and was a stand-in for some time as the title puppet’s manipulator), and has, lastly, been associated with the Pickwick Puppet Theater for the past several years. It was as a member of this company that she confronted the world of rock and roll music eye-to-eye, when she appeared on Broadway at the Uris Theater with the British group. Mott the Hoople. (She manipulated a Sancho Panza puppet in the song “Marionette.”)

TS; Yes, I was elected to appear witn the one big head that had been built, on a couple of television shows (TV was all live at the time) shortly after the movie had opened. I was to demonstrate how the film had been made using the heads, but we had the fake computer setup there also, to give the impression that the head was electrically operated—when it was really worked manually. We still had to keep that a big secret!

CU: Being a novice to the stop-motion process, with only a three-week training period behind you didn’t you find this form of animation slow and tedious?

TS: No, I found the more involved I got and the more intricate the movements got, that it was anything but tedious. Some time after the film was completed I worked on a few commercials for cosmetics—Hazel Bishop lipstick, and I think Myerberg was involved with these, as we filmed them in the five-story building on East Second Street he had bought. I believe we utilized the GRETEL puppet in them . . .

Speaking of that three-week training period, I remember I was petrified when it was over—I didn’t think I was ready to go immediately to work on the film, but they said, “Go onl You’re ready!” I and another person being trained acted out little scenes with some of the puppets. Animating them walking, and doing various movements of the hands . . . The scenes would be filmed and then played back for us so we could spot our mistakes. Since money was low they only filmed a few tests for each person.

CU: How did the tests turn out?

TS: Believe it or not, they came out very well! Surprisingly so! The idea was not to be jerky, but to have smooth action, moving the puppets in small increments. When doing the actual animation for the film, we would all act out the various scenes first, in front of a mirror.

CU; Were any animators assigned to do a certain character and that character only, or did you all take turns with the various figures?

TS: Since we had two crews working, when you came in to work your next shift you would carry on from where the previous people left off, no matter which figures were in the scene. It turned out that generally I stayed with GRETEL, or the mother—I did her a great deal of the time, and I did the witch one day too. You know, we had these awful stereotypes in those days … the women puppeteers would animate the female figures and the men did the males, which is ridiculous!

CU: That’s sort of a “too many cooks spoiling the broth” situation, though. Each character should really have its own “personality ” – a way of walking and moving that is that one figure’s alone, and is given to that character by one animator alone. If you recall the feature YELLOW SUBMARINE, there’s a scene where the four eel-animated Beatles are walking down a long flight of stairs, and each Beatlo has been given a very distinctive walk that’s carried throughout the entire film. You can tell which Beatle is in a scene without seeing his face!

TS: Yes. As a matter of fact, HANSEL had a definite little personality, and he would have to be done by someone who was more familiar with that kind of boyish movement, i recall, having worked with GRETEL so much, that after a while she started getting “tacky” looking and they had to have another figure of her made. They were having difficulty making her look the same as the previous model.

One strange piece of animation I and a few others worked on was a “burst of light” effect we were trying to achieve. We had 6,000 jewels on the ground on a piece of black velvet, and each jewel had to be moved separately for an effect that lasted only a few seconds on the screen. We’d be down on our hands and knees moving the gems, and people would walk by and burst out laughing!

Animating the descent of the agels from their fairy kingdom.

Pictured are (clockwise) Danny Diamond, Kermit Love, Joe Horstman,

Sky Highchief, Teddy Shepard, and outside of circle (arms

crossed) Roger Caras.

CU: What’s your opinion of the final film? Do you think it would have turned out better if you had been given more time?

TS: Certainly. There was such a rush on towards the end, money was running out and we were working so hard to finish … we were all really learning the process, too. When I first saw the finished movie back in 1954, I was initially disappointed, but I think it’s held up quite well with the passage of time. And those figures were so beautiful . . . you could get so many intricate moves with them, more so than any other stop-motion models I’ve ever seen!

Other animated commercials produced by Michael Myerberg Productions during the early 1950′s (commercials whose profits were immediately used to forward production of the HANSEL AND GRETEL feature) were several for Ivory Soap Flakes (for which a mother and baby were constructed) and Ehler’s Coffee (a butler). Sometimes finished figures were built specifically to interest potential new customers. (A Kool Cigarette Penguin, and a Lil Abner model were examples of this policy.) When all plans for future stop-motion animation projects were finally abandoned, Myerberg returned to the role of theater producer for the Broadway stage.

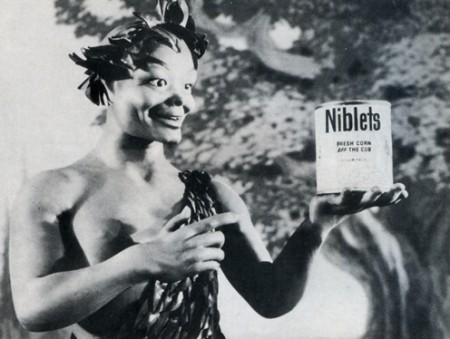

Michael Myerberg utilized the KINEMINS technique on television commercials

as well as feature films. ABOVE AND BELOW: A GREEN GIANT figure

sculpted by James Summers, circa 1953. A Speedy Alka-Seltzer model

was also sculpted, but never used. Monetary problems continually plagued

Myeiberg, forcing many of his innovative ideas to remain on the drawing board.

ARE ANY OF THE ORIGINAL KINEMINS STILL IN EXISTENCE?

Tragically, no! In late 1955, vandals broke into the East Second Street studio and wrecked havoc among the stop-motion models and scenery which were in storage there. Most of the figurines were smashed beyond repair, but, hoping that one or two models might have been carried away intact, Myerberg notified the local police station, telling them that the KINEMINS skin was highly toxic to human beings. Unfortunately, this story brought no results.

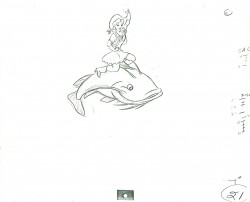

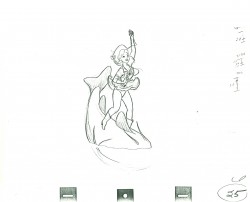

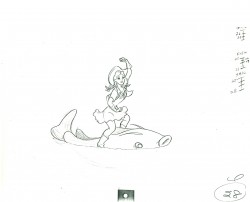

Animation &Disney 12 Apr 2010 08:09 am

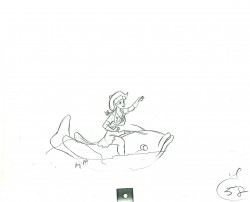

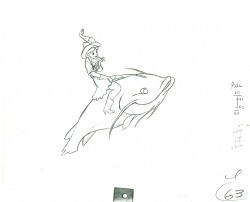

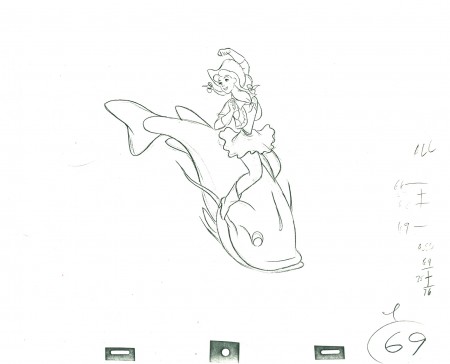

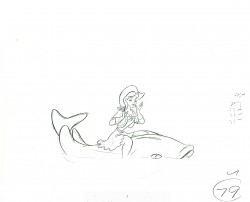

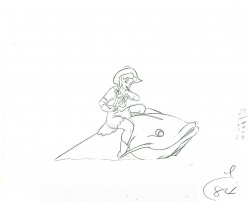

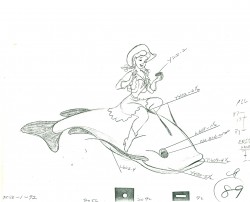

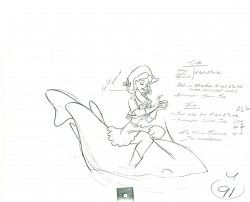

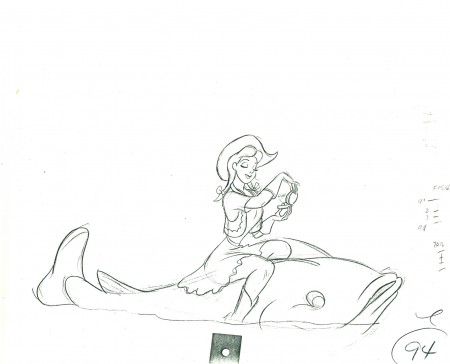

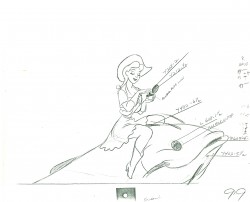

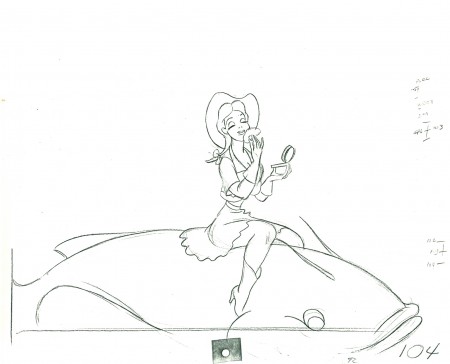

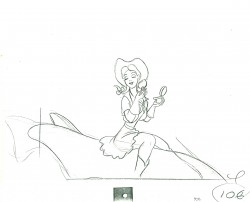

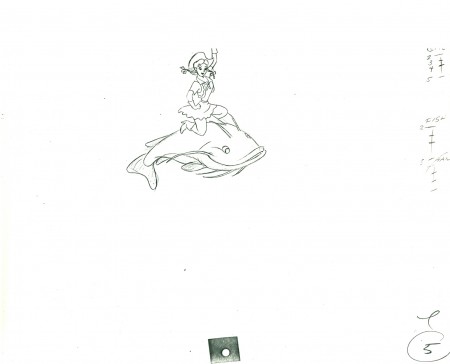

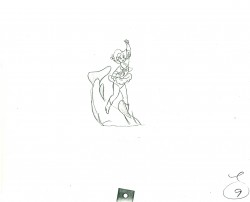

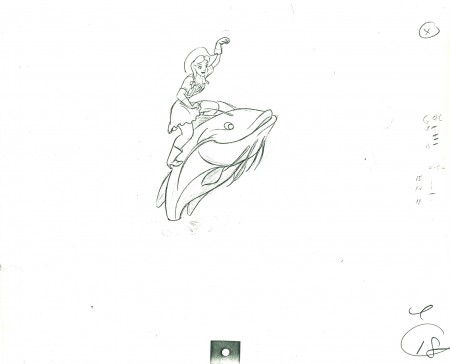

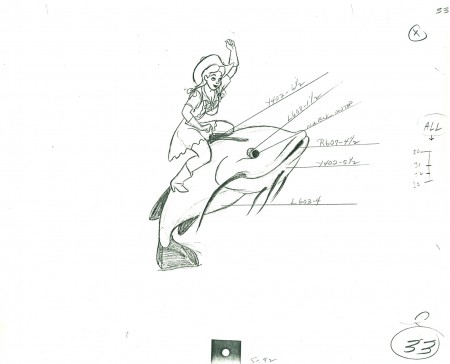

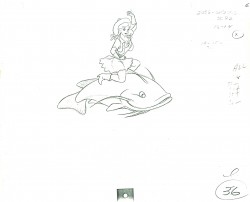

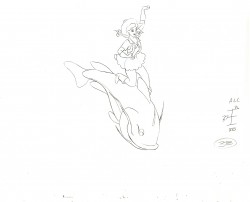

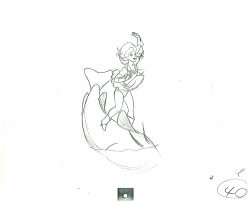

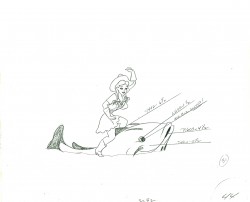

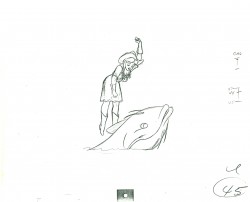

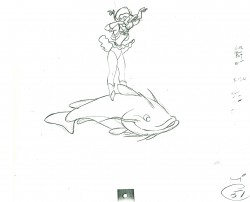

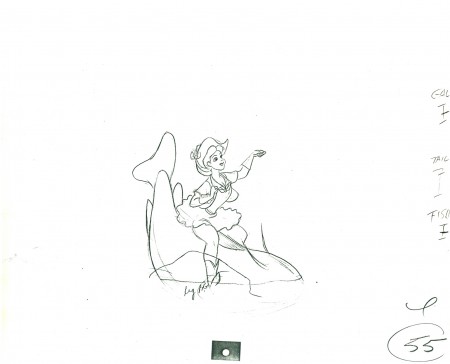

Slue Foot Sue – 2

- Today we complete the posting of animation drawings from this scene from Pecos Bill, animated by Milt Kahl. It’s a shot of Slue Foot Sue riding a large fish into the foreground. The drawings are on loan from Lou Scarborough, and I thank him much for the letting me showcase the work.

Here’s the link to last week’s post – Slue Foot Sue – Part 1

As always, we start with the last drawing shown last week.

55

55

The following QT represents all the drawings from the scene. Each

extreme was held for the appropriate number of frames requested.

Right side to watch single frame.

Animation &Commentary 07 Apr 2010 10:03 am

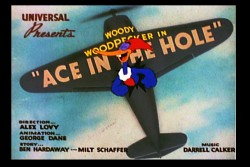

Ace in the Hole

- Back in the day, when I was just a teenager, there was very little in the way of media, as there is today. If you were desperate to become an animator, there weren’t many directions to turn. You had what was on the four or five tv channels that existed and there was the library.

- Back in the day, when I was just a teenager, there was very little in the way of media, as there is today. If you were desperate to become an animator, there weren’t many directions to turn. You had what was on the four or five tv channels that existed and there was the library.

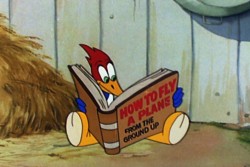

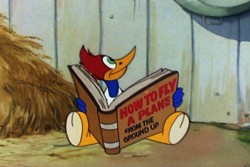

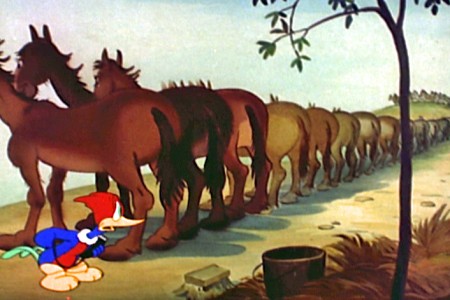

TV offered the Walt Disney show, which two out of four Wednesdays (later Sundays) each month, they’d touch on “Fantasyland”, and  you could watch some Disney cartoons – usually Donald and Chip & Dale, or there was the Woody Woodpecker show, during which Walter Lantz would talk for four or five minutes about some aspect of animation.

you could watch some Disney cartoons – usually Donald and Chip & Dale, or there was the Woody Woodpecker show, during which Walter Lantz would talk for four or five minutes about some aspect of animation.

For all those other hours of the day when you wanted animation you had to make do with what you could create for yourself.

At the age of 11, I took a part time job for a pharmacist delivering drugs to his clientele.

I lived off the tips that were offered, and I saved my money until I had enough to buy a used movie camera. The trek into downtown Manhattan was a big one for an eleven year old child, but I loved it. I went by myself to Peerless camera store near Grand Central Station. (It later merged with Willoughby to become Peerless-Willoughby; then it went back to just being Willoughby.)

I lived off the tips that were offered, and I saved my money until I had enough to buy a used movie camera. The trek into downtown Manhattan was a big one for an eleven year old child, but I loved it. I went by myself to Peerless camera store near Grand Central Station. (It later merged with Willoughby to become Peerless-Willoughby; then it went back to just being Willoughby.)

That store, I quickly learned had a large

section devoted to films for the 8mm crowd. Lots of Laurel and Hardy, Our Gang and Woody Woodpecker cartoons. Once I had the camera, I saved for a cheap projector and eventually bought some 8mm cartoons.

section devoted to films for the 8mm crowd. Lots of Laurel and Hardy, Our Gang and Woody Woodpecker cartoons. Once I had the camera, I saved for a cheap projector and eventually bought some 8mm cartoons.

Independence. Now, I didn’t have to wait to see them on TV, I could project them myself whenever I wanted. Even better, I jiggered the projector to maneuver the framing device which allowed me to see one frame of the film

at a time, so that I could advance the frames one at a time. I could study animation.

at a time, so that I could advance the frames one at a time. I could study animation.

I know, I know. I’m describing the stone ages. Today all you have to do is get the DVD (which is incredibly cheap compared to the cost of those old 8mm films) and watch it one frame at a time or any other way you want. And every film is available. If you don’t have it just join Netflix and rent it. Your library is always open and growing.

Yes, Peerless had an large 8mm film division, so you could buy the latest Castle film edition of some Woody Woodpecker cartoon, or you could find many of Ub Iwerks’ films. I had a collection of these. Ub Iwerks was my guy. Everything I’d read about him (in the few books available) got me excited about animation. Actually, Jack and the Beanstalk and Sinbad the Sailor were the first films I’d bought and watch endlessly over and over frame by frame.

Yes, Peerless had an large 8mm film division, so you could buy the latest Castle film edition of some Woody Woodpecker cartoon, or you could find many of Ub Iwerks’ films. I had a collection of these. Ub Iwerks was my guy. Everything I’d read about him (in the few books available) got me excited about animation. Actually, Jack and the Beanstalk and Sinbad the Sailor were the first films I’d bought and watch endlessly over and over frame by frame.

In short time, I knew every frame of Jack and the Beanstalk backwards and forwards. I didn’t realize that it was Grim Natwick who had animated (and directed the animation) on a good part of the film. Meeting Natwick years later, I think I surprised him by saying as much. He just moved on to another subject, appropriately enough.

In short time, I knew every frame of Jack and the Beanstalk backwards and forwards. I didn’t realize that it was Grim Natwick who had animated (and directed the animation) on a good part of the film. Meeting Natwick years later, I think I surprised him by saying as much. He just moved on to another subject, appropriately enough.

In some very real way, I learned animation from that film and several others that I

bought in those primative years of my career. Before I knew principles of drawing, I’d been able to figure out principles of animation. I’d had the Preston Blair book, and I had the Tips on Animation from the Disneyland Corner. I just measured what they said about basic rules and watched – frame by frame – how these rules were executed by the Iwerks’ animators. The rest was up to me to figure out, and I was able to do that.

bought in those primative years of my career. Before I knew principles of drawing, I’d been able to figure out principles of animation. I’d had the Preston Blair book, and I had the Tips on Animation from the Disneyland Corner. I just measured what they said about basic rules and watched – frame by frame – how these rules were executed by the Iwerks’ animators. The rest was up to me to figure out, and I was able to do that.

Eventually I bought a Woody Woodpecker cartoon. I was reluctant because so many of them were the very limited films done in the early 60′s – Ma and Pa Beary etc. It took a while to figure out that Ace in the Hole was a wartime movie and the animation would be a bit better. It was also the Woody that I liked – just a bit crazy. So I sprang for it and swallowed that film’s every frame for years.

Eventually I bought a Woody Woodpecker cartoon. I was reluctant because so many of them were the very limited films done in the early 60′s – Ma and Pa Beary etc. It took a while to figure out that Ace in the Hole was a wartime movie and the animation would be a bit better. It was also the Woody that I liked – just a bit crazy. So I sprang for it and swallowed that film’s every frame for years.

I’m not sure who George Dane is, (he seems to have spent years at Lantz before working years at H&B and Filmation) but I studied and analyzed his animation on this film closely and carefully.

I’m not sure who George Dane is, (he seems to have spent years at Lantz before working years at H&B and Filmation) but I studied and analyzed his animation on this film closely and carefully.

The work reminded me of some of the animation done for Columbia in the early 40′s. It had that same mushiness while at the same time not breaking any of the rules. Regardless, he knew what he was doing, and I had a lot to learn from him. And I did.

Things keep changing, media keeps growing. I’m glad I had to fight to get to see any of those old 8mm shorts back in the early years. When I bought my first vhs copy of a Disney feature, it took a while to grasp the fact that I could see every frame of it whenever I wanted. In bygone years, I could only see the rejects that TV didn’t want. I wanted to study Tytla and Thomas and Natwick and Kahl. Instead, I studied George Dane. And you know what, it was pretty damn OK. I

Things keep changing, media keeps growing. I’m glad I had to fight to get to see any of those old 8mm shorts back in the early years. When I bought my first vhs copy of a Disney feature, it took a while to grasp the fact that I could see every frame of it whenever I wanted. In bygone years, I could only see the rejects that TV didn’t want. I wanted to study Tytla and Thomas and Natwick and Kahl. Instead, I studied George Dane. And you know what, it was pretty damn OK. I  learned enough that I knew a lot when I started in the business. I just jumped in and was animating for John Hubley within days of getting that first job. (It helps that it was an open studio like Hubley’s where the individual artist could do anything, as long as he kept his head above water. In most studios there’s a rigidity that keeps you in your classified job.) In fact by then, I was more interested in Art Direction and Direction than I was in animation, but that’s another post.

learned enough that I knew a lot when I started in the business. I just jumped in and was animating for John Hubley within days of getting that first job. (It helps that it was an open studio like Hubley’s where the individual artist could do anything, as long as he kept his head above water. In most studios there’s a rigidity that keeps you in your classified job.) In fact by then, I was more interested in Art Direction and Direction than I was in animation, but that’s another post.

If you want to learn from the masters, just pop in a DVD and watch it frame-by-frame. If you don’t get a charge out of it, you might begin to wonder if you’re really in the right business. After all these years, I still get the thrill, and I imagine I always will – even from watching Ace in the Hole AGAIN.

Animation &Articles on Animation &Independent Animation &Puppet Animation 06 Apr 2010 06:15 am

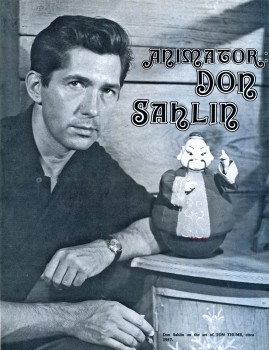

Don Sahlin

- After posting some stills from Ray Harryhausen’s Golden Voyage of Sinbad, I decided to look back and see if there were any other material I could post about 3D model animation.

I came upon this interview with Don Sahlin in Closeup Magazine, no. 2. published in 1976 by David Prestone.

(Bio)

Born in Stratford, Connecticut, Don Sahlin (say—lien) was introduced to the world of marionettes at age eleven, when he saw a production of HANS BRINKER AND THE SILVER SKATES by the New York Marionette Guild.

Born in Stratford, Connecticut, Don Sahlin (say—lien) was introduced to the world of marionettes at age eleven, when he saw a production of HANS BRINKER AND THE SILVER SKATES by the New York Marionette Guild..

Joining the PUPPETEERS OF AMERICA organization, he was soon inundating many of that group’s members with letters of inquiry as to the correct method of constructing and performing marionette shows. This correspondence brought Don an offer from Rufus Rose (who, several years later, was to create all of the figures for the HOWDY DOODY televison show) to spend several weekends with Rose and his wife as an apprentice.

.

In 1946, Don started another apprenticeship of many years standing when he began working with Martin and August Stevens, who performed sophisticated marionette dramas of subjects like Macbeth, Joan of Arc, and Cleopatra.

.

A stint of Summer Stock in Rhode Island followed, when Don felt he would try his hand at the acting profession, but he soon became disenchanted with this form of theater work. In 1949, Don traveled to Hollywood, where he worked with puppeteerist Bob Baker, doing party shows for many of the movie stars there.

.

Don then returned home to perform a show of his own designing, SAINT GEORGE AND THE DRAGON, which played around the Connecticut area. Later jobs involved working with very large puppets accompanied by a symphonic orchestra, Chinese shadow plays, and, in 1950, a marionette version of the LAND OF OZ stories that Burr Tilstrom was preparing as a television pilot. Working for a year on this project, Don was then drafted into the army.

CLOSEUP: How did you first get involved with stop-motion animation?

.

DON SAHLIN: When I got out of the Army in 1953, I had heard that Michael Myerberg was looking for puppeteers to work on HANSEL & GRET-EL. For some reason, he thought that puppeteers would make better animators than (stop-motion) animators! I was interviewed and got the job. I had to then go through a three-week training period with Myerberg in order to better acclimate myself with stop-motion. It was a very bizarre setup.

DON SAHLIN: When I got out of the Army in 1953, I had heard that Michael Myerberg was looking for puppeteers to work on HANSEL & GRET-EL. For some reason, he thought that puppeteers would make better animators than (stop-motion) animators! I was interviewed and got the job. I had to then go through a three-week training period with Myerberg in order to better acclimate myself with stop-motion. It was a very bizarre setup..

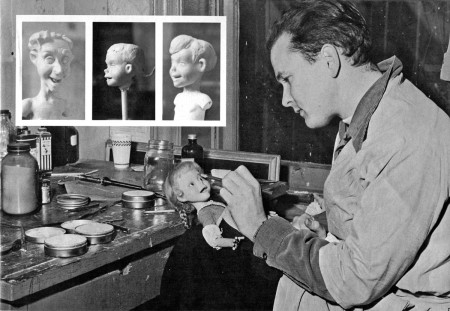

CU: Do you recall who sculpted the puppets?

.

DS: A man by the name of Jim Summers did the sculpturing. As I recall, they had a special machine shop where all the armatures were constructed. I’d give anything to own one of those armatures now. They were pieces of art.

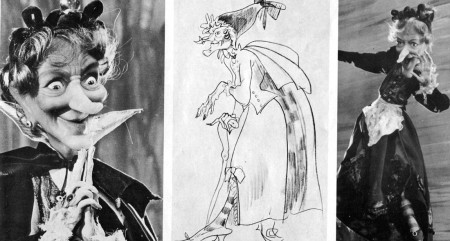

James Summers applies makeup to an almost finished Gretel.

Inset: Clay heads by Summers.

Below: Evil Witch Rosina Rubylips views herself

as portrayed in a preproduction sketch.

.

CU: Were they all ball-socket in construction?

DS: They were, but you’d press levers, which was really interesting. If you wanted to move the thigh, for instance, you’d press a little lever near the thigh area which would release it for a tiny movement. Removing pressure from the lever would freeze the puppet in position. As you may know, they were all held on the stage with electromagnets.

CU: Could you elaborate on how that was done? It’s interesting that Myerberg used that method of support as opposed to the tie-downs used by today’s animators. . .

DS: The base of the stage was all metal, and they had these strong electromagnets underneath. The puppets really clomped down on them. Of course, we’d have to break the electromagnetic field in order to move the legs to their next position. One night, as I remember, we were working on a very hard scene. Myerberg had a twenty-four-hour shift there, and the animation varied so greatly because people would come in and start animating where the day-shift had left off! We went out to dinner, and somehow, somebody had hooked the electromagnets into the main power source. Naturally, we killed all the lights as we went out. As we pulled the switch, we heard a series of plops. All the puppets had fallen over! We had to start the whole thing all over again! I quit twice on that film … I never got screen credit, because I quit before it ended.

CU: Here’s a quote from the book Puppet Animation in the Cinema: “The Kinemins used in HANSEL & GRETEL . . . were controlled by the use of electrical solenoids, and electromagnets in the feet. . . a system which is a closely-guarded trade secret…”

DS: (Laugh) That’s a lot of bunk, you know. The only thing “electronic” was the electromagnetic setup that held the puppets on the stage. Myerberg had a big panel upstairs where he’d use close-up heads that were wired to this big, blinking board. You’d turn knobs, but there was nothing electronic involved. There was simply a wire inside the mouth, and with a twist of a certain knob, the mouth would go “that way,” and so on. But it was all manual. Anything else that was said was a big put-on.

CU: A similar incident occurred with the publicity on Ray Harryhausen’s 7TH VOYAGE OF SIN-BAD, where the reporters of the media were quot-iny the producer on how the skeleton fight was “electronically” controlled . . .

DS: Nothing but press stuff, I would imagine. I’m glad you mentioned Harryhausen. God, I love his work. The one I saw recently again that I just adore was JASON AND THE ARGONAUTS. His work was absolutely superb. Classical mythology is such a wonderful area to explore. Why don’t they do more things like that?

CU: We’ve been asking ourselves the same question !

DS: Those skeletons were frightening! You know, I’ve learned to enjoy animation more now because I’ve been away from it for so long. But it’s a curious thing. Do you remember Trnka’s A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM? I saw it again and fell asleep through most of the whole thing! I was just so aware of how long it took to do each scene that it fatigued me … But it was a beautiful film.

CU: Getting back to HANSEL & GRETEL. Who actually did the camerawork on it?

DS: That was a very strange thing. Myerberg hired Martin Munkasci to photograph the animation. He was one of the great still photographers and had done a lot of things with Garbo and so on. Oddly enough, Myerberg felt that since stop-motion was nothing but a series of still frames, a capable still photographer would be more appropriate to do the camerawork. It was a very strange rationale on his part. Martin knew virtually nothing about motion pictures. Fortunately, a very fine Acme camera was used which was simple to operate, and he would just line up the shots and photograph. Anyhow, we went nuts, going up and down opening and closing those trapdoors all night long, sitting under that stage! And those sets were gigantic. Many of the backdrops were paintings, but a lot of it was also dimensional.

CU: We know that Myerberg isn’t with us anymore. What became of his organization after HANSEL & GRETEL?

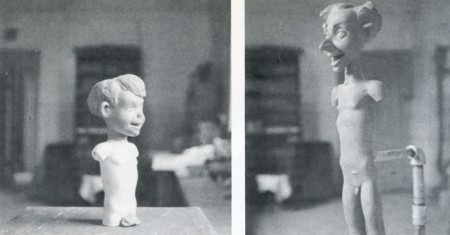

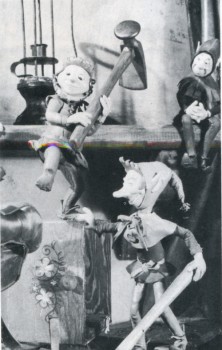

Above: The beginnings of the KINEMINS . . .

incomplete sculptures of Hansel and his father .

Below: Several puppet figures and a set (which predate all work

on HANSEL AND GRETEL) from ALADDIN AND THE WONDERFUL LAMP.

All sets and puppets for this project were put aside

once work began on the Humperdink musical.

.

DS: Myerberg had all sorts of aspirations to do other things, but they never materialized. I think his sons own the film now.

CU: Where did you go from there?

DS: After I left Myerberg, I was in association with Kermit Love, who had also worked on the film. We were going to do a full-length motion picture Of Beatrix Potter’s TAILOR OF GLOUCESTER. It’s a charming story about a tailor and a Whole community of mice. We were going to animate all of the mice. We had the whole thing set up in London . . . Robert Donat was signed to play the lead role and Margaret Rutherford was also cast for the film. We began building the mice and we had some funding, although we hadn’t gotten to the point where we were able to build them all. Suddenly, we had a bad partnership and the whole project collapsed.

CU: Would the animated mice have been combined with live actors in the same scene?

DS: No, they would have been separate. I don’t really like it when they combine things, although Ray Harryhausen is a master at it. I wouldn’t want to do it in that way, but I respect what he does very much. Anyhow, I returned to the States when our TAILOR OF GLOUCESTER failed, and then got 3 call to go out and do work on TOM THUMB. That film, I think, was the most enjoyable thing I worked on during this period, because it was my first big job in Hollywood.

CU: How did you get involved with George Pal?

DS: At the time, 1 had been out in California working with a puppeteer friend of mine named Bob Baker. When TOM THUMB began, I was asked to build a little six-inch stop-motion marionette of Tom that they were going to use in the long shots. It was a funny thing. They said that he had to wear a fig leaf, so I carved this puppet with ball and socket joints, and he really looked naked. George was in England shooting in 1957, and decided that he wanted the puppet for a particular scene. But all my work was in vain, because the fig leaf that Tom wore covered almost his entire body. I had thought that the fig leaf would be in scale with his body, but that’s not the way it turned out. I think Wah Chang has the little Tom Thumb figure now, but I would love to own it. It was really an exquisite little puppet. It was all carved out of walnut, and I filled the legs with lead to make them heavy. It was never used in the closer shots, just distance stuff.

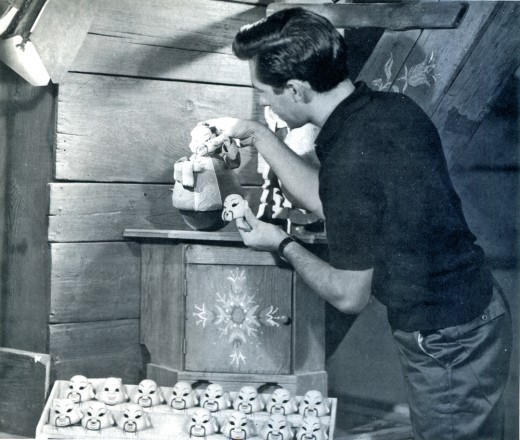

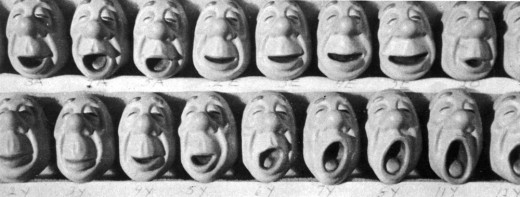

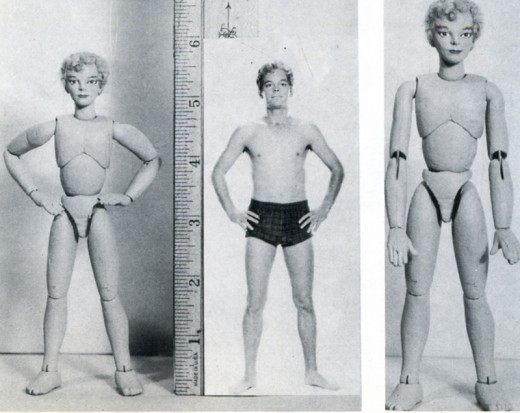

Two photos illustrating the replacement method of animation, utilized on TOM THUMB.

Instead of achieving changes of expression through manipulation of a stop-motion model’s

facial features, a series of heads are prodced, each head having a slightly different

expression on it. Changes are made by simply substituting one head for another.

Above: Don Sahlin placing a head on Con-fu-shun, and

Below: Numbered heads created for The Yawning Man animated by Gene Warren.

.

CU: How did you get to be a part of Project Unlimited?

DS: After I had carved the little stop-motion marionette, they started filming all of the animation sequences, but 1 had to go back to New York. Then Bob Baker called me from California and told me that they needed an animator. I talked to Wah Chang, I think it was, and he said, “Come on out and work for us!” 1 worked out at Project until about 1962. They wanted me to stay on, but Burr Tillstrom of Kukla, Fran and Ollie fame wanted me to come back to New York to work with him on a Broadway show. And it’s funny how fate is. I didn’t want to go; I really loved working at the studio, especially after THE TIME MACHINE. Anyhow, I did go to work for Burr on this small, cabaret-type show at the old Astor Hotel, but it soon folded. And like I say, 1 regretted leaving Hollywood, but I also met Jim Henson of the Muppets here in Mew York, and it led to probably my most successful period.

CU: Could you tell us just what you animated on TOM THUMB?

DS: I animated Con-fu-shun, a lot of the little guys that just popped up, and the Jack-in-the-Box. Gene Warren and I did all of the animation, just the two of us. Gene is a marvelous animator; he did the Yawning Man sequence. I spoke to Gene a little over a year ago, and I was so happy to find out that he does my favorite commercials—Chuck-wagon! To me, the most charming commercials ever done!

CU: What were some of the techniques used in animating Con-fu-shun?

DS: I remember Con-fu-shun was a very simple puppet. The armature was bolted to the stage and he just rocked. Occasionally, I think he got off for a couple of drop shots. The facial expressions were accomplished by replacing just the faces, which were made out of wax. We had a whole tray of all his faces. We’d just put on “E1″ or “E2,” or “Smile 1,” “Smile 2.” I know his eyes were not connected to the face; they were always independent. The faces just slipped on in perfect registration. I remember the little eye-pick I used for animating his eyes; it looked like a little hypodermic needle.

The TOM THUMB marionette created by Don Sahlin and used only in long shots.

CU: Did you have anything to do with constructing the large prop furniture, or giant hands and horse’s ears, that Russ Tamblyn was to interact with?

DS: No, that was all done at MGM, in England. Project Unlimited was a kind of neat little studio by itself, completely independent. Pal would do all of his stuff at MGM, but I wasn’t involved in the work done there, even on THE TIME MACHINE.

CU: You did some work on DINOSAURUS. Could you talk a bit about it? We know that,the models were built by Marcel Delgado, but little is known about who actually did what as far as the animation goes . . .

DS: I animated the Tyrannosaurus and the fight scenes that were involved with it. The rest of the animation was done by myself and Tom Holland; he got to do most of the Brontosaurus, the less ferocious of the creatures. I remember the night we finished the scene where the Brontosaurus died in the quicksand. The material used for quicksand was Fuller’s earth; I guess it’s used because it looks in scale. We had a kind of screw-jack that the puppet got on, and we kept pulling it down slowly in stop-motion, beneath the surface of the quicksand. When we finished the scene, we were exhausted. Then we asked ourselves, “Should we leave him in or take him out,” this great piece of sponge rubber? So we pulled him out again and we were hosing him off and cleaning him up. It was funny!

I also remember the night the big dinosaur fight took place. They were playing Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring in the background and boy, it really inspired us to animate! We got through that fast, where they were tearing and ripping at each other.

CU: Is Tom Holland still animating in Hollywood?

DS: I don’t know what Tom is doing now. It’s interesting; Tom wasn’t really an animator. He was an actor, primarily, and he somehow got involved in animation. We did all of those scenes together. I recall another amusing incident on DINOSAURUS. Do you remember those close-up shots of the manually-operated dinosaurs that we intercut? We once spent a whole day boiling ochra and straining it to make it look like saliva was really dripping from their mouths. It was just hideous!

CU: DINOSAURUS is an interesting thing to look at as an animation film, but technically, it did seem to be somewhat under par in comparison with some of the others. . .

DS: It was a very cheap film. A lot of the rear projection work was just awful, especially the scene at the beginning when the guy came running out of the shack and the dinosaur came to life. Those shots were far from pleasing.

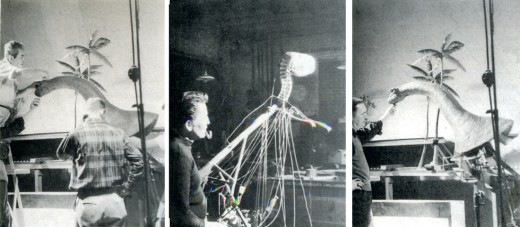

Project Unlimited technicians working on the large

manually-operated dinosaurs created for DINOSAURUS.

Left: Marcel Delgado applies the finishing touches to the Brontosaurus mockup.

Middle: Tom Holland and the Tyrannosaurs Rex “skeleton”.

CU: How big were the models in DINOSAURUS?

DS: Most of them were relatively small, except for the Brontosaurus, which was awfully big. You probably remember that we had a little doll of a boy riding on its back. I have a theory that large figures are hard to animate. Something happens, some strange phenomenon, which I can’t understand, takes place. I guess I’m not that kind of a perfect animator; I sort of do it loosely. I did TOM THUMB because that was all very contained. I got a lot out of the character as far as hand movements and so on. But the stuff that Jim Danforth did for BROTHERS GRIMM was just so superb that I would go insane doing that. I’m really into marionettes; I think that there’s a lot of potential in them for fantasy films in certain instances. I remember telling Gene Warren about some of those long shots where they were Trudging through the jungle in DINOSAURUS: “You know, I could do that better with marionettes.” I really think that one can augment the two.

CU: Project Unlimited also did some work on SPARTACUS…

DS: Yes, our little studio was always doing unusual props and effects for films, in between our animation jobs. Kirk Douglas was producing and starring in a monumental production of SPARTACUS, and Project Unlimited was called in to make about ‘ two or three hundred dead bodies, in various f scales, for some of the battle scenes. The largest * were about one-third life-size … We used molds to make them, and then we’d dress them in armor and sort of strew them all over the battlefields. I then i had to slash and “gore them up” with fake blood! We also made a bunch of horses out of polyure-thane foam. They weren’t very detailed, though-we just had to make sure they’d be recognizable from a distance, but none of them were shown in closeups.

CU: What did you do on THE TIME MACHINE?

DS: I worked on virtually all of the special effects.

There really wasn’t much animation, other than the decaying Morlock. That was done by Tom Holland. You know, I was in that film! I made my “screen debut.” Remember the guy in the window changing the clothes on the mannequin? That was me! I didn’t want the job because there was an actor there who worked with us, Dave Worrick. I asked them to give the job to Dave because I had no real desire to be in films. But they said, “No, we want you to do it.” So they got me a costume and animated me for the scenes.

CU: You mean you were actually pixillated as opposed to just speeding up the camera?

DS: Yes. I literally went in and they animated me per frame. The really neat thing about changing all of those costumes dealt with the fact that they were brought in from MGM. Somehow, in my subconscious mind, I recognized them. I remember saying to myself, “I’ll bet that’s a Lucille Ball dress.” Sure enough, it was, as their names are all sewn in them. But I loved the Morlock scenes. Some of the things I wish I had taken were a pair of Morlock feet and a Morlock head. They were great works of art; really spooky to look at! 1 animated the airplanes and dirigibles in the World War II scenes, but I never thought they were very realistic.

CU: In the earlier part of the film, there was a split-screen shot where boiling lava came oozing down the street. . .

DS: That was a great big fiasco, you know, because it didn’t really work. They had built these two bins full of colored oatmeal for the lava. One day, they decided to do a take. They covered all of the set with polyethylene. Now, they had prepared the oatmeal the night before, and nobody got up to look at it. Then they pulled the traps, with all these high-speed cameras going, and all the oatmeal had fermented and became watery. And the sight of all that! If I could have had a picture of the faces on those people! This foul-smelling, fermented mess came rushing down over all the cameras. I just went home. When they did the take again, they had put too much stuff together and it was too thick. I believe that’s how it appeared in the film. We were busy throwing burning cork and silvery material into the oatmeal, but it really didn’t work too well. It was fun, though.

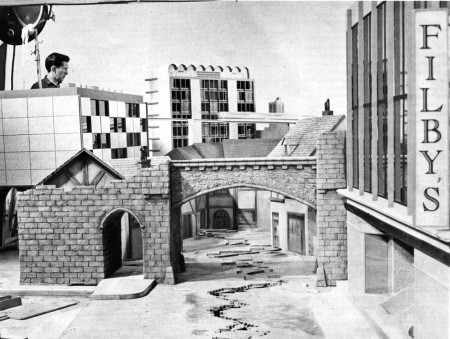

Don Sahlin on THE TIME MACHINE set.

Down this street will come the colored oatmeal “lava” flow.

CU: There was some inconsistency with the shot of you changing the mannequin. If the sun had been rising and setting at the speed depicted in the film, you shouldn’t have been able to see a man change a mannequin at all…

DS: Right. There are a lot of inconsistencies in that picture, but they’re very minor. It’s such a charming thing to watch. I never get tired of seeing it; it has such a haunting quality to it.

CU: Even the music and the actors seemed perfect.

DS: It did have a good score. Rod Taylor certainly seemed to be suited for the role. I had never been much of an Alan Young fan, but he played that triple role beautifully. And Yvette Mimieux was just out of high school at the time. The sound effects were great. I especially loved the off-camera sounds of the kettles underneath the ground.

CU: Did you work on the explosion scene towards the end?

DS: We had an incredible effect for that. We built a huge miniature set, about the size of a good-sized living room. It was all done on different levels of tables. We had legs underneath; and it was like a big puzzle. The legs were pulled at different times so the set would collapse. Then there would be explosions and flash-pots going off. It was really effective. There were many other scenes in THE TIME MACHINE that I worked on. There was the opening scene of the candles melting, and the ones of the flowers blooming. I remember we animated a snail; I also animated the Sphinx. You might recall the raising and lowering of those siren towers …

CU: Were they cardboard cutouts or was it a full miniature?

DS: It was dimensional. But there was very little animation involved in that. There was another scene, a blue-backing shot, where layers of lava were made to appear rising behind Rod Taylor in his Time Machine. That was all painted. They had a guy in another room, Bill Brace, an artist, and he was doing all those matte paintings where the trees were blooming and the apples were growing. And he painted the future scenes, too, where you saw the topography of the land changing, and the Eloi temple being built. The whole dome of that was a painting matted in, and the stairway leading up to it was part of MGM’s old QUO VADIS set.

DS: It was dimensional. But there was very little animation involved in that. There was another scene, a blue-backing shot, where layers of lava were made to appear rising behind Rod Taylor in his Time Machine. That was all painted. They had a guy in another room, Bill Brace, an artist, and he was doing all those matte paintings where the trees were blooming and the apples were growing. And he painted the future scenes, too, where you saw the topography of the land changing, and the Eloi temple being built. The whole dome of that was a painting matted in, and the stairway leading up to it was part of MGM’s old QUO VADIS set.

Do you know what I loved about working on TIME MACHINE? We literally did the sets ourselves. I loved doing the sets and dressing them. We were all very involved in the whole project instead of just one aspect of it. I remember working on that huge hole that Rod Taylor climbed into to get to the Morlock world. I loved getting down there, touching it up with a spray can and adding little details to it. I really feel proud to say that I worked on THE TIME MACHINE; I think it was a classic. I never received screen credit due to the politics of the organization, but it never bothered me. We were working on a very small budget. I think I remember Gene telling me that we did the effects for under $60,000, which was really a smal sum, yet it reaped an Academy Award. Have yot ever met George Pal?

CU: We’ve never had the pleasure.

DS: When you think about him, he was such an unusual producer when you realize the courage he had to have to do the kind of offbeat things he did.

CU: The last film you worked on for him was THE WONDERFUL WORLD OF THE BROTHERS GRIMM. Could we talk about what you did on that one?

CU: The last film you worked on for him was THE WONDERFUL WORLD OF THE BROTHERS GRIMM. Could we talk about what you did on that one?

DS: I did a lot of the animation, especially the scenes involving the elves. The opening scene of the elves took me a whole week to do. Dave Pal and George’s other son, Peter, worked with me. We got along famously. I had to leave before the picture was over, so Dave carried on from where I left off.

CU: Did you work with Jim Danforth on the film?

DS: Not directly. I was in one corner of the stage, and Jim was working in the other corner. It was so tedious because of the Cinerama camera. Each frame had to be photographed three times. You had to be careful not to make any mistakes. We couldn’t talk at all. Peter would work the camera and we made it a point never to talk to each other because it was so easy to make an error. I was animating five elves, and he had to work that complicated turret camera.

CU: Didn’t you have to brace some of the elves? Some of them had to leap off the stage. . .

DS: Yes. We had a lot of wire stuff on the film. The wires were very thin and they were coated with iodine. You really couldn’t see them. Each time we’d reposition the puppet, the wires would be in a different part of the frame. So they really cancelled themselves out.

CU: Did anything unusual happen on the animation set?

DS: I do remember one funny thing that happened on BROTHERS GRIMM. There was a scene where an elf walked across the set with a shoe. The peg holes, by the way, were covered with clay and painted to match the set each time the elf took another step. Anyway, one of my little mice from the aborted TAILOR OF GLOUCESTER project got into a frame while the elf was being animated. Just for one frame. It was a terrible thing, but Pal never saw it!

CU: Did you do anything outside of the elf sequences?

DS: Wah Chang set up all of the shots and lit them. While he was doing that, I loaded the camera, which to this day frightens me because I don’t consider myself that technically inclined. I also did all of the calibrations and animated the camera for trucking shots. All the fades and the simpler opti-cals were done in the camera.

CU: Did you actually plot out all of the animation before it was photographed?

DS: We had to on some of the things. When there are faces involved as there were in TOM THUMB, and you have to do all the vowels and so on, you have to plot them out beforehand. But I like to animate sort of “free;” I don’t like to be restricted too much. You mentioned Jim Danforth before. I believe I met him while I was doing TOM THUMB. He was very young at the time and was very wide-eyed at what was going on. He seemed so impressed with our setup. Then I saw his reel that he had done in his garage. He did incredible stuff, op-ticals and everything. He’s a genius; he really is an incredible animator. He’s so much better than I am because I haven’t the patience to do the detail that he does. I remember him animating the dragon in BROTHERS GRIMM. He did that whole thing, and he spent days with all sorts of pointers. He’s a perfectionist.

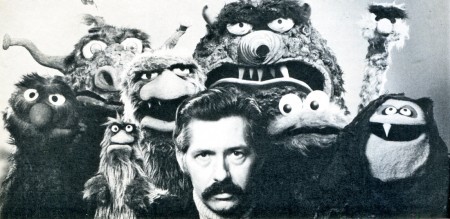

CU: Now that you’re no longer involved in stop-motion, could you tell us about your work with the Muppets?

DS: I build and co-design Jim Henson’s puppets. He starts out with a little thumbnail sketch; I would say that he really creates the essence with his sketch. Then I start building it. Jim comes in and looks at it and we play with them to see how well they’ll work. But it’s really a joint effort, although I don’t do any of the puppeteering. I built many of the most famous of the Muppets. Kermit the frog, Bert and Ernie, the Cookie Monster, and most of the others.

CU: You did two “counting films” for Sesame Street. . . were these very recent?

DS: Not really. They were done around 1970, right here in our Muppets, Inc. offices. Jim Henson supervised the filming, but he gave me all the freedom in the world to do what I wanted. THE QUEEN OF SIX was filmed on a rug, to simulate grass, and the backgrounds were all painted cardboard. The Queen figure was about 13 inches tall and I wanted her to have a very baroque, dresden sort of look. Her hoop skirt was a big lampshade that I put brocade on. She had a beautiful Marie Antoinette wig that I made out of silver thread, and I used one of those plastic Easter eggs you can buy for her head.

DS: Not really. They were done around 1970, right here in our Muppets, Inc. offices. Jim Henson supervised the filming, but he gave me all the freedom in the world to do what I wanted. THE QUEEN OF SIX was filmed on a rug, to simulate grass, and the backgrounds were all painted cardboard. The Queen figure was about 13 inches tall and I wanted her to have a very baroque, dresden sort of look. Her hoop skirt was a big lampshade that I put brocade on. She had a beautiful Marie Antoinette wig that I made out of silver thread, and I used one of those plastic Easter eggs you can buy for her head.

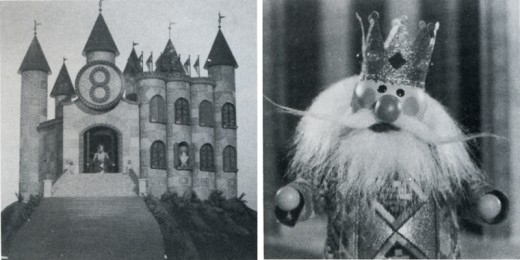

CU: I recall the other “counting film” you did, THE KING OF EIGHT, with the rhyme-speaking king, and his eight daughters opening and closing the windows of his castle. Both of these films were fairly short, weren’t they?

DS: Yes, none of those films done for Sesame Street are over a minute in length.

The King of Eights

CU: Are you satisfied with the work you’re doing now?

DS: Certainly. It’s very creative and enjoyable. I remember that when I was a kid, my sister wanted me to take regular college courses. I told her I wanted to take art courses. She would say, “What can you do with art? You’ll never make a living do ing puppets.” And it was only recently that we reminisced about that and, not trying to sound egotistical, I said to her: “Do you know that my puppets are all around the world?” Now that Sesame Street has been distributed in Europe, I have great satisfaction in knowing that my creations are

being seen and enjoyed internationally.

Don, as he appears today, with some of his more

“gruesome” creations for the Henson MUPPETS.

Animation &Disney 05 Apr 2010 07:27 am

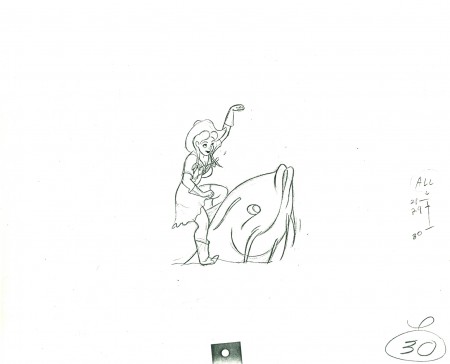

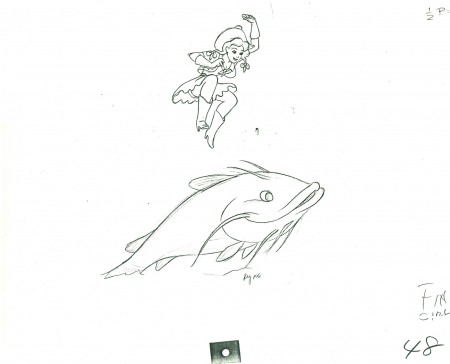

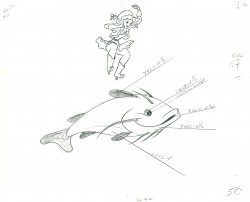

Slue Foot Sue – 1

- Here’s Slue Foot Sue riding a fish in the Disney short Pecos Bill. The piece was animated by Milt Kahl and loaned to me by my friend, Lou Scarborough. I’ve had to split the drawings into two – Part 2 will be posted next week.

Three of the drawings in the entire piece were traced rather than xeroxed and these three won’t have to be pointed out.

1

1  2

2(Click any drawing to enlarge.)

The following QT represents all of the drawings from the scene,

not just those seen above. Each extreme was held for the

appropriate number of frames requested.

Right side to watch single frame.

Animation &Puppet Animation 03 Apr 2010 07:53 am

Bill Benzon/Harryhausen

- Bill Benzon has been writing some particularly fine pieces for The Valve, and he just posted a lengthy and heady article called The Rings of Fantasia. When Bill notified me about the piece, I asked if he minded my reposting on my site, and we agreed to go ahead with that. However, after doing all the work of setting it up, I’ve decided it’d be wrong to do so. It’s better just to link to it so that The Valve, the original site that Bill regularly writes for, will get as much attention as it deserves for showcasing such a writer as Bill.

I suggest you check it out and read some of the many other pieces Bill’s written. He’s a great supporter of Nina Paley’s work, currently highlighting the web comic strip she’s doing, Mimi and Eunice. (It’s good to see Nina creating again after the long promotional wind-down of Sita Sings the Blues. By the way, Bill Benzon wrote a wonderful and positive piece for The Valve about that film, as well.)

So in the end, let me encourage you to go and read. There’s some great stuff by Bill Benzon at The Valve.

- Clash of the Titans opened yesterday to mediocre and negative reviews. Watching trailers for this film made me sad to see the work of Ray Harryhausen tramped on by the cg generation. There’s no possibility a computer driven model could carry the same weight that the magnificent creatures of Harryhausen brought to the orginal. His films were always annoying in that they had a bevy of bad acting and live-action direction all in the service of the brilliant effects. Harryhausen’s creatures were the real stars of his films whether Jason and the Argonauts, either of his two Sinbad movies or Clash of the Titans. Even watching the clips of the cg effects brought me down. Something about the original’s stop-motion jerkiness added a weight, a reality to the form. The computer effects have become so generic that to go from this film to even the Mummy movies becomes almost interchangeably tedious. There’s basically no difference and no reason to see the film.

Instead I did see a running of the original and several other Harryhausen films on TCM recently. The mix of greatness and the B-movie live-action was almost delightful. These films have become iconic, and they’re irreplaceable.

To honor Harryhausen, I want to post some production stills. I don’t have pictures from his Clash of the Titans, but I do have plenty on The Golden Voyage of Sinbad, the film just prior to that. So here are some of those images.

1

1(Click any image to enlarge.)

2

2

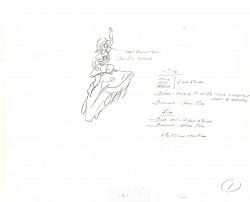

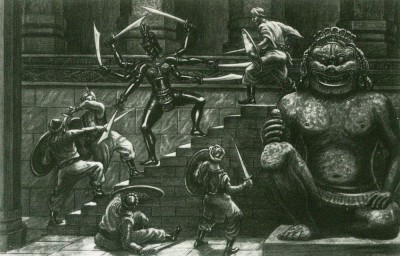

The original drawing of Sinbad and his men

fighting the golden Kali.

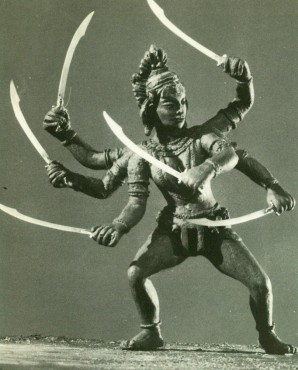

3

3

The golden Kali comes to life.

4

4

Very complicated staging of the sword fight had to be done

to keep the scene looking authentic.

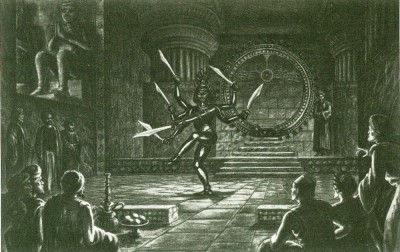

6

6

An early Harryhausen preproduction drawing of Kali dancing.

7

7

The magician beckons Kali to descend the stairs.

8

8

John Stoll designed and supervised the many sets for the film.

Fernando Gonzalez was the Art Director.

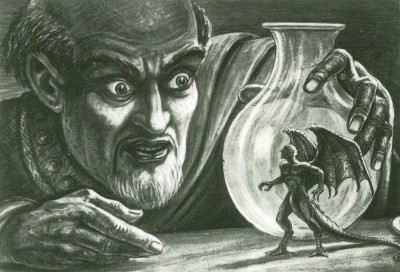

9

9

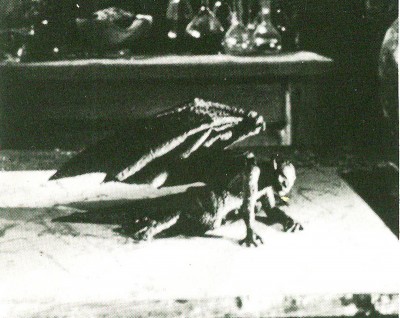

An early Harryhausen preproduction drawing of the Homonuclus.

10

10

Kaura and Achmed look on in wonder as

the Homonuclus comes to life.

11

11

The Homonuclus first tries out its movement.

12

12

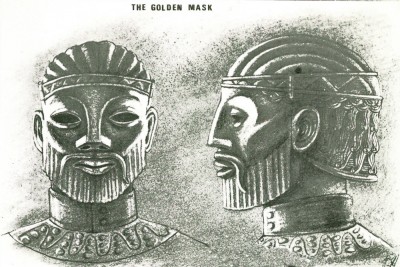

Designs for the Golden Mask worn by the Vizier whose face

has been disfigured by Koura the Magician.

14

14

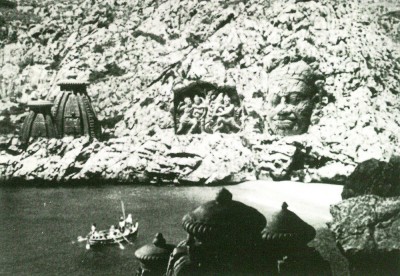

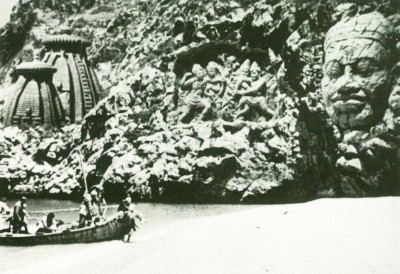

Beach scenes of Majorca substituted for

the Ancient continent of Lamuria.

15

15

The construction in the beach wall and the ship were added later.

16

16

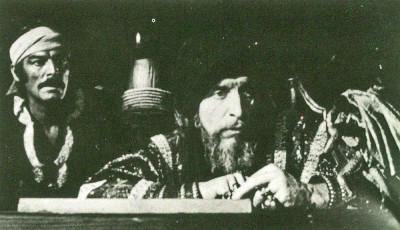

Haryhausen (R) and cinematographer, Ted Moore (L), on the set.